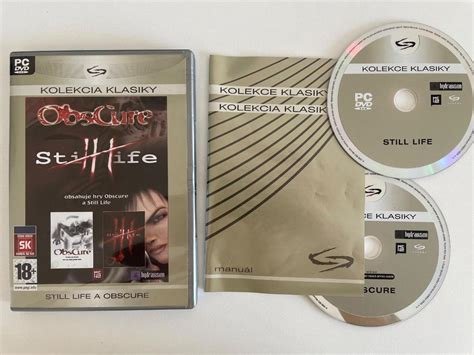

- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: MC2-Microïds

- Genre: Compilation

- Average Score: 66/100

Description

The ‘ObsCure / Still Life’ compilation bundles two distinct games: ObsCure, a survival horror set in Leafmore High where students discover a secret laboratory beneath their school, conducting experiments that create mutated monsters, and must rescue a missing friend while battling for survival; and Still Life, a separate 2005 title included in the package, offering an additional gameplay experience without specific premise details provided in the source text.

Gameplay Videos

ObsCure / Still Life Cracks & Fixes

ObsCure / Still Life Guides & Walkthroughs

ObsCure / Still Life Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (66/100): It’s very much like a video game equivalent of the teen-horror genre – whilst it does make you jump in places, it won’t give you nightmares.

ObsCure / Still Life: A Dual Review of Compilation and Cult Classics

This review examines the 2006 compilation ObsCure / Still Life, a package pairing two distinct but thematically linked titles from the mid-2000s: Hydravision Entertainment’s teen survival horror ObsCure (2004) and Microids Canada’s neo-noir adventure Still Life (2005). While superficially dissimilar—one a cooperative action-horror romp through a monster-infested high school, the other a solitary, puzzle-driven detective thriller spanning two centuries—both games are products of a specific era in European game development. They represent a bold, if flawed, attempt to adapt American genre tropes (the slasher film, the hardboiled mystery) through a French lens, all while operating under the technological and fiscal constraints of the early 2000s. This compilation, primarily a European budget release, serves as a curious time capsule, capturing two games that were modest successes at launch but have since accrued passionate cult followings. Their legacies are intertwined by a shared publisher (MC2-Microïds), a thematic fascination with hidden darkness beneath mundane surfaces, and a common fate of narrative incompleteness. This analysis will dissect each title’s ambitions, mechanics, and historical impact before evaluating the compilation’s own role in preserving these obscure artifacts.

Development History & Context

The story of ObsCure begins with Hydravision Entertainment, a small French studio founded by Denis and François Potentier. Initially creating tabletop RPGs like Zombies, How to Enjoy Deadly Nights, the studio pivoted to video games around 2000 with Microïds’ backing. The original concept was a Lovecraftian tale, but market pressures and a desire for accessibility led to a radical shift. Heavily influenced by late-90s teen horror films like The Faculty and Scream, the team crafted a game that was both a homage to Resident Evil and a deliberate subversion of its lonely, solitary atmosphere. The core innovation—mandatory, seamless two-player cooperative gameplay—was a direct response to the genre’s norm. Using the RenderWare engine, popular for its cross-platform compatibility (PS2, Xbox, PC), Hydravision crafted detailed, gloomy 3D environments. The development was characterized by a small team (around 20 core members) wrestling with the engine’s limitations, resulting in technical quirks like fixed camera angles that sometimes hindered control. The soundtrack, a major strength, was composed by Olivier Derivière, whose eerie, choir-backed score created a deliberate dissonance with the “totally radical” teen dialogue. Released first in Europe in late 2004 and delayed for North America until April 2005 by DreamCatcher Interactive, its launch was overshadowed by giants like Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas.

Still Life emerged from a different strand of Microïds’ operations: Microids Canada (formerly Adventure Soft). It was a direct sequel to Post Mortem (2003), itself part of a planned trilogy. The game was built using the Virtools engine, a common tool for adventure games of the period, and its design philosophy was rooted in the classic point-and-click tradition established by games like Syberia. Directed by Desmond Oku (who also worked on ObsCure) and designed by Mathieu Larivière, it prioritized atmospheric storytelling, intricate puzzles, and a grim, neo-noir aesthetic. The dual-timeline narrative—jumping between 2004 Chicago and 1920s Prague—was its central structural gimmick. Development was smoother than ObsCure’s, but the game was conceived as the middle chapter of a trilogy. When Ubisoft acquired Microïds Canada in 2005, the future of the series became uncertain, though a sequel, Still Life 2, would eventually materialize in 2009. The Xbox version notably used the “Live Aware” feature for minor online stat tracking, a precursor to modern achievement systems.

The 2006 compilation itself, released by MC2-Microïds for Windows, was a value proposition aimed at the European budget market. It had no significant technical enhancements or added content, simply bundling two previously released games. Its existence speaks to Microïds’ strategy of repackaging their mid-tier catalog and the games’ complementary, if contrasting, appeal: one an action-oriented horror, the other a cerebral adventure. The compilation is now a rarity, with physical copies sought after by collectors, while both games found new life in a 2014 Steam HD remaster (which altered ObsCure’s soundtrack due to licensing issues) and through emulation communities.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

ObsCure: The Mortifilia Conspiracy

ObsCure’s plot is a distilled essence of late-90s/early-2000s teen horror. It opens with a prologue where basketball star Kenny Matthews is lured into the basement of Leafmore High, discovering a secret lab and a mutated student named Dan. Dan’s immediate death establishes the “Anyone Can Die” rule. The main narrative begins the next day, as Kenny’s friends—his intelligent sister Shannon, his cheerleader girlfriend Ashley, reporter Josh, and stoner Stan—break into the locked school to find him. They soon encounter light-sensitive monsters born from the Mortifilia plant, a luminescent African flora that promotes cellular regeneration but twists victims into grotesque, shadow-cloaked creatures. The mystery unfolds through VHS tapes, notes, and environmental storytelling, revealing the conspiracy: Principal Herbert Friedman and his twin brother Leonard, aided by nurse Elisabeth Wickson and biology teacher Denny Walden, have been kidnaping students for over a century to find an immortality serum. Leonard, the first test subject, is a monstrous, root-like entity imprisoned in a deep basement lab.

The plot is structurally simple, progressing through distinct school wings (gym, library, cafeteria, dorms, administration) toward the underground facility. Themes are blunt but effective: the corruption of innocence (students becoming monsters), the horror of institutional betrayal (teachers as villains), and the scientific hubris of pursuing eternal life. The teen archetypes are deliberately shallow—a critique echoed in many contemporary reviews—but this serves the B-movie homage. The “Good Ending” (all five survive) sees the group destroy Leonard in sunlight, only for a post-credits scene to hint at lingering threats. The “Bad Ending” (anyone dies) shows a funeral where a corpse emits spores, implying the infection persists. The narrative’s greatest weakness is its abruptness; the final confrontation and resolution feel rushed, a flaw the developers acknowledged by making ObsCure II more dialogue-heavy.

Still Life: Echoes of a Serial Killer

Still Life presents a more sophisticated, layered narrative. FBI Special Agent Victoria McPherson, in Chicago for Christmas 2004, inherits her grandfather Gustav “Gus” McPherson’s notebook. Gus, a Prague PI in the 1920s, investigated a series of murders of prostitutes by a cloaked, silver-masked figure. Victoria discovers her own case—murders at a high-end S&M club, the Red Lantern—mirrors Gus’s findings with chilling precision. The gameplay alternates between Victoria in 2004 Chicago and Gus in 1920s Prague, a dual-timeline structure that reveals parallels and suggests a copycat or a legacy of evil.

The story is a slow-burn detective noir, heavy with atmosphere and literary references (the title points to the artistic technique of arranging inanimate objects, a metaphor for Victoria’s attempt to “arrange” clues into a coherent picture). Themes include the cyclical nature of violence, the weight of family history, and the elusive nature of truth. Unlike ObsCure, the villain’s identity is deliberately withheld; Victoria confronts the 2004 killer multiple times but never sees his face. The climax sees her shoot him, but he escapes into the Chicago River, leaving the case open. A stinger reveals similar murders in 1931 Chicago and 1956 Los Angeles, and a secret society, Delta Theta Gamma (ΔΘГ), is hinted at as a greater-scope villain—a thread picked up in Still Life 2. The game’s infamous lack of a true ending was a direct consequence of Microïds Canada’s acquisition and the planned trilogy’s disruption. This narrative incompleteness is its most defining feature, frustrating players but cementing its status as an “unfinished” artistic statement.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

ObsCure: Coop, Light, and Permadeath

ObsCure is a third-person survival horror with fixed camera angles and a fully 3D environment. Its gameplay is a hybrid of Resident Evil’s inventory management and puzzles with unique twists:

- Character System & Permadeath: Five playable teens, each with a special ability: Kenny (fast sprint, melee damage), Ashley (rapid-fire pistol), Shannon (puzzle hints, 20% better healing), Josh (detects items/puzzles in a room), Stan (faster lockpicking). Crucially, none are required to progress; any character can perform any action, albeit slower or harder without their perk. The game implements true “permadeath”—if a character dies, they are gone for good (except Dan, who is scripted to die). The campaign continues with survivors, but losing key characters (like Stan for lockpicking) makes sections harder. The “Good Ending” requires all five to live.

- Light as a Weapon: The core mechanic. All monsters are shrouded in a “dark aura” that must be dissipated by flashlight beams before they can be harmed. Flashlights can be taped to guns (using Adhesive Tape) for simultaneous use, though they overheat. Smashing windows lets in sunlight, which insta-kills exposed foes. This “weakened by light” system was innovative for its time, predating Alan Wake’s similar focus.

- Cooperative Mode: The game’s flagship feature. A second player can join locally at any time, taking control of the AI partner. Players can switch characters on the fly to use abilities. The AI is competent but human coordination is superior. This mode fundamentally changes the experience, reducing horror but enhancing chaotic fun. It was widely praised as a standout feature.

- Inventory & Progression: Shared inventory for items (health, ammo, keys), but weapons are character-bound. Resources are scarce, encouraging careful management. Save points are limited collectible CDs. Puzzles are largely light-based or “solve the soup cans” (e.g., use acid on chains, use projector to reveal a safe code). The game is short (5-6 hours), with New Game+ offering alternate costumes and powerful weapons.

- Flaws: Clunky tank controls, frustrating camera angles in tight spaces, repetitive enemy encounters, and an abrupt final act in the maze-like underground lab. The story delivery is also criticized for being too brief and lacking character development outside the opening.

Still Life: Point-and-Click Detective Work

Still Life is a pure graphic adventure, a genre in decline by 2005 but still thriving in Europe. Its gameplay is deliberate and cerebral:

- Dual-Timeline Structure: The player alternates between Victoria McPherson in 2004 Chicago and Gus McPherson in 1920s Prague. Progress in one timeline often unlocks locations or provides clues for the other. This creates a complex, non-linear narrative web.

- Point-and-Click Interface: Using a cursor, players examine scenes, collect items, and combine them in inventory to solve puzzles. There is no combat. The challenge lies in environmental logic and item combination. Puzzles range from straightforward (find a key) to obscure (use a specific object on a specific environmental detail).

- No Hand-Holding: The game provides no objective list or hint system. Players must deduce next steps by reviewing collected documents in the menu or by exploring. This can lead to frustrating “moon logic” but rewards attentive, methodical play.

- Static Presentation: Scenes are rendered in beautiful, pre-rendered 3D backgrounds from fixed angles. Character movement is slow and deliberate, a common critique of adventure games. The Xbox version’s controller support was particularly panned for being clunky.

- Narrative Pacing: The game is structured in acts, with each character’s chapter comprising several locations. The pacing is slow, focused on building atmosphere through dialogue, voice acting (solid but not exceptional), and the grim, painted visuals.

- Flaws: The infamous lack of a resolution is its biggest flaw. The game ends on a cliffhanger, with the 2004 killer’s fate ambiguous and the ΔΘГ conspiracy teased but unexplated. This was not a creative choice but a consequence of cancelled sequel plans, leaving players feeling cheated. Some puzzles are overly obtuse, and the pacing can drag.

World-Building, Art & Sound

ObsCure: The American High School as Gothic Labyrinth

Leafmore High is the game’s greatest asset. It’s an “Elaborate University High”—a private institution with impossibly lavish facilities: a botanical garden, a theater, a maze of underground tunnels, and dormitories. The architecture is Art Nouveau, with a cloister-like central courtyard and creepy statues, giving it a gothic, timeless feel that contrasts with its American high school trappings. The art direction deliberately mixes the mundane (classrooms, lockers) with the monstrous (spore-covered walls, mutated vegetation). The atmosphere is dense with fog, shadows, and oppressive silence broken by the children’s choir in Derivière’s soundtrack. This score is a masterpiece of dissonance: ominous, Latin-tinged chants underscore the cornball teen dialogue, creating a unsettling, almost parodic tension. The monsters are body-horror personified—students twisted into Biter, Crawler Fly, and ArbolTrebol forms, their vulnerability to light a clever gameplay integration. The world feels lived-in but sinister, a perfect setting for a B-movie plot.

Still Life: Neo-Noir Across Two Centuries

Still Life trades ObsCure’s gothic horror for a rain-slicked, chiaroscuro neo-noir aesthetic. The 2004 Chicago sequences are all neon reflections, dark alleys, and the sterile interiors of the Red Lantern club. The 1920s Prague sequences are even more painterly, with gas-lit streets, sepia-toned interiors, and a palpable sense of historical decay. The visual style is heavily influenced by film noir and classic detective fiction, with a muted color palette and dramatic lighting. The score by Tom Salta is a moody, jazzy, and electronic hybrid that perfectly complements the investigative mood. The world-building is environmental storytelling at its finest: Gus’s Prague is a city of shadows and pre-war tension; Victoria’s Chicago is a modern metropolis hiding ancient sins. The ΔΘГ symbol, a recurring visual motif, hints at a larger conspiracy that feels organic to the settings. The game’s greatest strength is its immersive, cinematic presentation of these two intertwined crime stories.

Reception & Legacy

ObsCure: From Mixed Reviews to Cult Classic

Upon release, ObsCure received “mixed or average” reviews (Metacritic: 63-66/100). Critics praised its cooperative mode (IGN: “almost worth the price of admission alone”), its light-based combat mechanic, and its atmospheric soundtrack. The high school setting was seen as fresh. However, it was widely criticized for derivative gameplay (GameSpot called it a “blatant rip-off” of Resident Evil), clunky controls, repetitive puzzles, and a shallow story with static characters. The short length (5-6 hours) and awkward camera were frequent complaints. European reviews were slightly more favorable than North American ones, perhaps due to the earlier release date and different market expectations.

Commercially, it was a modest success, selling an estimated 110,000 units. It was a budget title from DreamCatcher, which was struggling financially, and its November 2004 EU release was overshadowed by GTA: San Andreas. Physical PS2 copies are now rare collectibles ($100-$450). Its legacy underwent a significant rehabilitation. By the 2010s, it had become a cult classic, praised for its B-movie charm, innovative co-op, and bold premise. The 2014 Steam HD remaster (with updated graphics and widescreen support, albeit sans licensed music) introduced it to a new generation, garnering “overwhelmingly positive” user reviews (95% as of late 2025). It is now cited as a trope maker for its light-weakening mechanic and as an early example of accessible co-op in horror. Its influence is indirect but notable; games like Alan Wake later popularized a similar light-vs-darkness mechanic. The sequel, ObsCure II (2007), attempted to address criticisms with more dialogue and character development but suffered from “Sudden Sequel Death Syndrome,” killing off returning heroes. The planned third game morphed into the action-oriented Final Exam (2013), a spiritual successor rather than a direct sequel, after Hydravision’s closure.

Still Life: The Adventure That Never Ended

Still Life received fairly favorable reviews (Metacritic: PC 75, Xbox 70). Critics lauded its atmosphere, presentation, and intricate plotting. IGN called it “an enjoyable albeit short diversion.” However, it was faulted for sluggish movement, occasionally obtuse puzzles, and, above all, its complete lack of an ending. Eurogamer’s scathing review noted it did things well but failed on fundamental adventure game design. The unresolved cliffhanger was a deal-breaker for many and a direct result of Microïds Canada’s acquisition by Ubisoft and the shelving of the planned trilogy.

Commercially, it and Post Mortem sold over 500,000 units combined by 2008, with Still Life alone surpassing 240,000. This was solid for a niche adventure game. Its legacy is that of a beautiful, frustrating masterpiece-in-progress. It is remembered for its stylish noir visuals, its ambitious dual-timeline narrative gimmick, and its profound narrative injustice. The eventual release of Still Life 2 in 2009 provided some closure, but the original remains a tantalizing “what if.” It has been retrospectively celebrated by adventure game enthusiasts; Adventure Gamers named it the 20th-best adventure game ever in 2011. Its influence is seen in later detective adventures that embrace non-linear storytelling and atmospheric density.

Conclusion: The Value of the Obscure

The ObsCure / Still Life compilation is more than a simple repackaging; it is a historical artifact that juxtaposes two divergent design philosophies from mid-2000s Europe. ObsCure is a genre mashup—part teen slasher, part survival horror—that prioritized cooperative innovation and B-movie energy over polish. Its legacy is its influence on co-op design and its cult status as a charmingly flawed gem. Still Life is a genre purest—a point-and-click detective saga—that sacrificed player satisfaction for narrative ambition and aesthetic rigor, leaving a haunting, unfinished story that lingers in the memory. Both games are defined by a sense of incompleteness: ObsCure through its abrupt plot and cancelled sequel plans, Still Life through its literal non-ending.

Together, they represent a dying breed of mid-tier European games: ambitious, idiosyncratic, technically limited, but bursting with personality. They are games that tried something different—co-op horror, dual-timeline noir—within the constraints of their genres and budgets. Their flaws are glaring: clunky controls, thin characters, unresolved plots. Yet their strengths—atmospheric soundtracks, unique central mechanics, compelling settings—have resonated more deeply with time than contemporary critics allowed. The 2006 compilation, now a collector’s item, performed a vital service by preserving both titles together. In the 2020s, their availability on Steam and through emulation ensures they are no longer “obscure” in the truest sense. They are studied, remembered, and loved as cult classics—testaments to an era when a French studio could make a resonant American teen horror, and a Canadian team could craft a noir epic that left its audience desperate for the next chapter. Their place in history is secure not as pinnacles of their genres, but as bold, flawed, and unforgettable experiments that continue to cast a long shadow.