- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Kedamonoware

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Shooter

Description

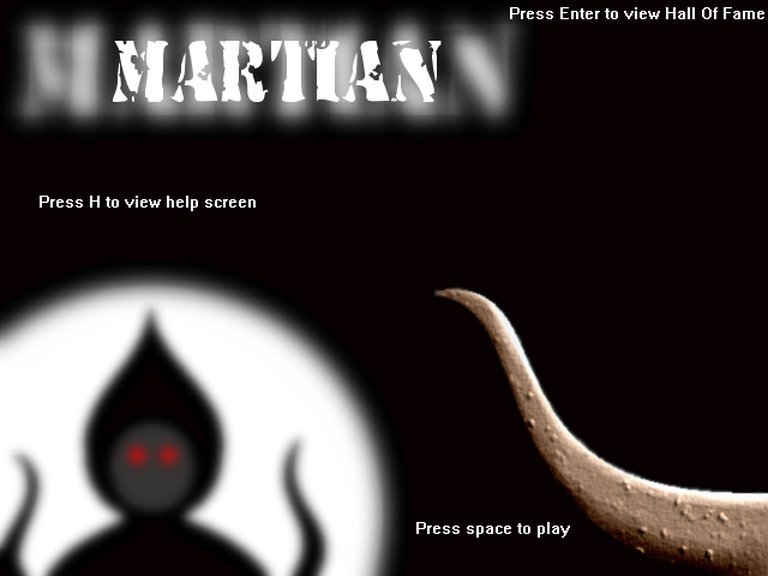

Martian is a freeware crosshair shoot ’em up game released in 2001 for Windows, where players control a hover-tank to defend nuclear missiles from an invading alien army. The gameplay involves using the keyboard for tank movement and the mouse for crosshair aiming, with progressively increasing difficulty and a selection of four weapon types.

Where to Buy Martian

PC

Martian Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com : I thoroughly enjoyed the game through all its issues.

Martian Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes when over the ‘HINTS FOR VIDEOGAMES’ book in the inventory.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| YOULOOKINATME | Infinite Health |

| IFEELUNUSUAL | Infinite Ammo |

| QUICKSUCKITOUT | Immune to Poison |

| PATRICKMARLEY | Listen to Darnley Microcorder |

| ILOVETHISGAMEWHOMADEIT | View Credits |

PlayStation 1 (Cheat Device Codes)

Enter codes through a cheat device such as CodeBreaker, GameShark, or Action Replay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 8010F624 0064 | Infinite Health for Karne |

| 8010F72C 0064 | Infinite Health for Kenzo |

| 8010F834 0064 | Infinite Health for Matlock |

| 800A11AE 0000 | Unlimited Ammo for Piccolo |

PlayStation 1 (In-Game Codes)

Enter codes at the corresponding locations in the game.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 4864 | Releases Karne at Park Lane Hatch |

| 3172 | Releases Kenzo at Psionara Case |

| 2915 | Releases Matlock at Bio Lab Computer |

| 2734 | Opens Airlock #3 for Matlock |

| 3376 | Opens Arboretum Door |

| 1010 | Opens Downing St. Hatch |

| 3471 | Opens Kremlin Door |

| 5748 | Opens Kremlin Weapon Room |

Martian: Review – A Tale of Two Martians, One Name, and a Deeply Confusing Legacy

Introduction: A Ghost in the Machine of Gaming History

To speak of “Martian” in the context of early 2000s PC gaming is to immediately wade into a morass of confusion. The name alone evokes a specific, almost forgotten artifact, but the provided source material presents a profound identity crisis. It bundles the scant documentation of a 2001 freeware arcade shooter—a modest, two-person project by Ben Hickling—with the exhaustive, multi-source chronicle of an entirely different game: Martian Gothic: Unification (2000), a ambitious survival horror title from Creative Reality. This review will navigate this treacherous terrain by first conclusively identifying the subject as the significantly more documented Martian Gothic: Unification, while explicitly acknowledging the existence of the unrelated 2001 shooter. The thesis is clear: Martian Gothic: Unification is a fascinating, deeply flawed “what-if” scenario—a game crippled by technological limitations, budgetary constraints, and a chaotic development history, yet one whose narrative ambition, thematic cohesion, and core gameplay twist elevate it above mere Resident Evil clone status into a cult curio of enduring historical interest. Its legacy is not one of commercial success or genre-defining innovation, but of poignant, often painful, evidence of a small studio’s struggle to manifest a complex vision on the cusp of a new millennium.

Development History & Context: The Last Gasp of a Small Studio

The story of Martian Gothic: Unification is intrinsically the story of Creative Reality, a UK-based studio on its final legs.

- The Studio and Its Twilight: Creative Reality, having previously released the cult adventure Dreamweb (1995), was a small team operating with limited resources. Martian Gothic was to be their last project before shuttering. This “project of last resort” context is crucial: every decision was filtered through a lens of severe time and financial pressure. The team, sharing members with Dreamweb, including writer Stephen Marley, understood narrative depth but was now attempting to pivot into the commercially dominant survival horror genre pioneered by Capcom’s Resident Evil (1996).

- The Vision and Its Metamorphosis: According to a 2011 Retroaction interview with writer Stephen Marley, the game’s origins were radically different. It began as a point-and-click adventure game internally titled “Unification,” named after a favorite Star Trek episode. When Marley joined, he rewrote the story and the genre was changed to action-adventure/survival horror to chase market trends. However, the adventure game’s DNA—the heavy reliance on inventory-based puzzles, environmental storytelling, and item combination—was never excised. This hybrid, schizophrenic identity is the game’s fundamental tension: it has the pacing and tension systems of survival horror but the puzzle density and item logistics of a classic adventure game.

- Technological Constraints & The Multi-Platform Struggle: The game was developed for Windows PC and, in a port handled by Coyote Developments, for the PlayStation. The PlayStation version, released a year later (2001 in EU/NA), represents a significant technical downgrade—lower resolution textures, occasional slowdown—but notably improved quality-of-life features, such as more frequent save points (12 per terminal vs. 2-4 on PC). This dual-release strategy on a tight deadline meant cuts were inevitable. Marley lamented that numerous features were scrapped: a final boss battle, a hint-giving NPC, a fourth playable character, alternate endings, and more fleshed-out areas in the alien Necropolis. The infamous “Martian Mayhem” mini-game, a supposedly terrible in-game arcade title, was conceptually larger but reduced to a mere save station mechanic.

- The Gaming Landscape of 2000-2001: The game arrived at the end of the PlayStation’s lifecycle and amidst the golden age of survival horror. It directly competed with the genre’s titans: Resident Evil 2 (1998) and Code: Veronica (2000), as well as * Silent Hill* (1999). Players expected specific conventions: tank controls, fixed camera angles, limited saves, resource management. Martian Gothic adopted these mechanically but subverted them thematically with its central “three characters, one rule” premise. It was a “budget title,” both in development scope and market positioning, inevitably compared to the polished, high-budget productions from Japan.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Masterclass in Squandered Potential

The narrative of Martian Gothic: Unification is its most celebrated and most tragic element. It is a story of remarkable density and cohesion that is consistently undermined by poor delivery mechanisms.

- The Premise and Core Mystery: In 2019, the Earth Control megacorporation’s Vita-01 base on Mars has been silent for ten months. Its final, desperate transmission: “Stay alone, stay alive.” A three-person team is dispatched: American security officer Martin Karne, British bacteriologist Diane Matlock, and Japanese systems analyst Kenzo Uji. Their shuttle crashes, forcing them to enter the base via separate airlocks—compliance with the warning. They discover a slaughterhouse: the crew is dead, then reanimated as “Non-Dead” zombies. The central, terrifying twist is the Trimorph: if any two team members come into physical proximity, the alien bacterial infection they carry (contracting during decontamination) causes them to violently merge with a third Non-Dead into a monstrous, amalgamated entity. This literalizes the warning and creates a permanent, paranoid state of separation.

- Characters Through Artefacts: The plot unfolds not through cutscenes, but via Apocalyptic Logs. Audio recordings, diaries, and terminal messages from the base’s deceased staff—particularly director Judith Harroway and the deranged medical officer John Farr (who adopts the Treasure Island alias “Ben Gunn”)—are the primary narrative vehicles. This method is atmospheric but exhausting; logs are lengthy (often 2-3 minutes), and the sheer volume can stall gameplay. The writing, by Stephen Marley, is sharp, blending scientific jargon with gothic horror and dark humor.

- The Unraveling Cosmic Horror: The mystery deepens from a zombie outbreak to a cosmic, parasitic horror. The crew had excavated an ancient alien sarcophagus (“Pandora’s Box”) from within Olympus Mons, awakening the hibernating Kurakarak Matriarch (referred to as “Queen Mab”). Her potent psionic powers induced shared nightmares, paranoia, and mass hysteria, leading to suicides and violence. The released bacterial contagion is her tool, encoding the memories and will of her extinct civilization. The infection is not a random plague; it’s a cognitive weapon designed to assimilate and transform.

- Character Arcs and Betrayal: The three investigators have hidden depths. Karne’s connection to Harroway (estranged partners) and his secret membership in an anti-corporate resistance cell provide a personal stake and a motive beyond rescue. Kenzo’s “techno-zen” demeanor is both a character trait and a gameplay necessity, as his emotional flatness allows him to interface with the base’s sentient AI, MOOD, without being driven mad. Diane’s microbiological expertise becomes vital for synthesizing a cure. The revelation that MOOD, the benevolent AI, has been secretly aiding them (via smartwatch passcodes) while harboring a grudge against Karne, adds a layer of digital paranoia.

- Thematic Cohesion: The game weaves several potent themes:

- Isolation as Survival: The “stay alone” rule is both a literal game mechanic and a thematic core about the erosion of self in the face of an assimilative, hive-minded threat.

- Corporate Arrogance: Earth Control’s desire to weaponize the alien psionic technology mirrors real-world ethical concerns about bioweapons and cosmic hubris.

- Gothic Architecture in Space: The title is literalized in the alien Necropolis beneath Olympus Mons—a subterranean, cathedral-like tomb of the Kurakarak, blending sci-fi with classic gothic imagery (shadowy vaults, ancient coffins, an overriding sense of dread).

- Identity and Assimilation: The Trimorph transformation is the ultimate loss of identity, a violent fusion that echoes the game’s own development struggles—different genres and ideas forced together into a dysfunctional whole.

The Fatal Flaw: This rich narrative is presented with static, low-poly 3D models against beautifully detailed pre-rendered 2D backgrounds. The voice acting is a mixed bag: Fenella Fielding’s silky, sinister MOOD is a highlight, while Kenzo’s emotionally flat delivery (intentionally directed, per Marley) and Karne’s slipped British accent (voiced by Rupert Degas) can break immersion. The story is there, brilliant and bonkers, but its delivery is often clunky and slow.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Triumph and Torment of the Trimorph Rule

The gameplay of Martian Gothic is a direct, often awkward, translation of its narrative premise into systems.

- The Three-Character Swapping System: This is the game’s defining, revolutionary, and most fraught mechanic. At any time, the player can press a button to instantly switch between Kenzo, Diane, and Martin. Each has a separate inventory, health, and location. The Cardinal Rule: If two characters occupy the same space, they instantly trigger the Trimorph transformation—a One-Hit Kill game over. This creates a perpetual state of anxiety. You are not controlling a team; you are managing three isolated survival units.

- Collaboration via Vac-Tube: To circumvent separation, the base is littered with Vac-Tube pneumatic delivery systems. You can send items (keycards, weapons, medkits, puzzle items) between characters. This is a clever logistical puzzle in itself. However, it is also the source of immense backtracking fatigue. You will spend hours running (with sluggish tank controls) between vac-tubes and safe rooms to shuttle equipment, all while managing limited inventory space.

- Combat: Incapacitation, Not Destruction: Enemies fall into three categories:

- Non-Dead: Classic shambling zombies. They cannot be permanently killed. Shooting them down only incapacitates them temporarily; they will rise again, faster each time. Their primary purpose is to be obstacles carrying necessary items (logs, keycards) that must be looted. They represent a persistent, respawning nuisance.

- Extrudes: Small, fast, parasitic crawlers that leap to poison or paralyze. They are trivial to kill with the nail gun but can overwhelm in groups.

- Trimorphs: The Advancing Wall of Doom. These hulking amalgamations are invulnerable to all weapons except the Flare Gun, obtained late in a grueling puzzle sequence. Encountering one means solving an environmental puzzle on the spot or dying. They are pure, unadulterated tension and a testament to the game’s core theme.

- Inventory & Resource Management: Inventory is tiny (6-8 slots). Ammo is scarce, health items are precious. Diane can synthesize medkits and, later, an antidote serum from herbs and alien samples, but this requires freeing her from her initial airlock trap and accessing the lab—a multi-hour process. The scarcity is authentic but often feels punitive due to the backtracking.

- Tank Controls & Camera: The game employs the classic Resident Evil tank control scheme (up = forward, down = back, left/right = rotate). Combined with fixed, often disorienting camera angles, navigation is deliberately clunky and tense. It makes evading the fast-moving Trimorphs a white-knuckle experience and turns simple movement through corridors into a chore. This is a double-edged sword: it builds atmosphere but frequently frustrates.

- The MOOD Interface & Saving: Accessing base computers allows you to query the AI MOOD for story clues, passwords, and system status. It also hosts the “Martian Mayhem” mini-game, a broken joke that serves as the only save mechanism in most areas (2-4 uses on PC, 12 on PS1). This limited save system is a classic survival horror trope but feels especially cruel given the game’s labyrinthine layout and instant-death Trimorphs. A late-game laptop allows free saving, a mercy that arrives too late for many players.

- Puzzle Design: Adventure vs. Horror: The puzzles are heavily inventory-based. You find a red keycard here, a power coupling there, a severed head (John Farr’s) elsewhere, and must combine/use them in distant locations. This is pure point-and-click adventure logic forced into a real-time 3D environment. Some puzzles are clever (using an airlock to space a Trimorph), others are Guide Dang It! obtuse (e.g., using a specific voice log to unlock a door). The adventure-game heart bleeds through, often to the detriment of the horror pacing.

Game-Breaking Flaws: The PC version is infamous for a critical bug in the vent sequence involving Diane and a Trimorph, where the shutter fails to close, making progression impossible without the official patch (which may itself introduce issues). The PS1 version is generally more stable but suffers from slowdown. Both versions feature notorious bugs, like respawning Extrudes in the Necropolis, that can create soft locks.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Study in Contrasts

The audiovisual presentation of Martian Gothic is a tale of two halves: one staggeringly effective, the other notoriously poor.

- Setting & Atmosphere: The Vita-01 base is a masterpiece of environmental storytelling. Its corridors are named after famous streets (Broadway, Mont St-Michel), a subtle touch that humanizes the cold Martian outpost. The base is divided into distinct zones: the lived-in, wood-panelled Rec Rooms; the sterile labs; the industrial power sectors; and the eventually accessible alien Necropolis. Each area tells a story through its decay, bodies, and scattered notes. The transition from the base to the barren, red Martian landscape and finally down into the ancient, eldritch Necropolis is a visual and tonal journey. The Necropolis, rendered in near-total darkness requiring night-vision goggles, is a perfect Eldritch Location—non-Euclidean architecture, floating bodies, and a pervasive sense of being watched by an ancient intelligence.

- Visuals: Pre-Rendered Majesty vs. Polygonal Mud: The 2D pre-rendered backgrounds are the game’s crowning visual achievement. For a small team, they are incredibly detailed, atmospheric, and varied. Sunlight streams through viewports onto metallic floors; labs are cluttered with equipment; the Necropolis is a haunting, shadowy void. The contrast with the 3D character and enemy models could not be starker. They are notoriously blocky, low-poly, and poorly textured. Characters look like slightly differentiated potato blocks. Enemies, especially the Trimorphs, are lumps of unrefined geometry. This dissonance breaks immersion constantly. The weapon models are equally unimpressive, contributing to a feeling of cheapness.

- Sound Design & Music: This is arguably the game’s strongest technical pillar.

- MOOD’s Voice: Fenella Fielding’s performance as the base AI is sublime. Her voice is seductive, ominous, and dripping with theatrical, gothic menace. Her quips during game-over screens (“How very… clumpy“) are legendary among fans.

- Ambient Dread: The soundscape is dominated by creepy ambient noise: the hum of machinery, distant metallic groans, and, crucially, the paranormal whispers and psychic murmurs that imply the Matriarch’s presence. These are effective and deeply unsettling.

- Scare Chord: The loud, jarring musical stinger when a Non-Dead grabs you is a classic, if cheap, jump-scare tactic.

- Music: The main menu theme is memorable and gothic. In-game music is sparse, relying more on ambient sound. The soundtrack by Jeremy Taylor (firQ) is minimal but thematically appropriate.

- The “Dissonant Serenity” of Kenzo: Kenzo’s ultra-calm reaction to floating corpses and psychic whispers (“Huh. Interesting.”) becomes a bizarre, almost comedic, but intentional part of the atmosphere. It underscores his “techno-zen” persona and makes his rare moments of concern feel significant.

Reception & Legacy: The “Missed Opportunity” That Refuses to Be Forgotten

- Critical Reception at Launch (2000-2002): Reviews were mixed to negative, with aggregate scores in the 59-65% range (GameRankings) and a Metacritic score of 64 for the PS1 version. Critics were divided:

- The Positives (IGN, Eurogamer, PC Gamer): Praised the engaging, if derivative, story, the unique three-character mechanic, the strong atmosphere, and the clever puzzles. Duncan Turner at IGN noted it had “a lot to offer.”

- The Negatives (GameSpot, GameSpy): Dismissed it as a “missed opportunity” (Steve Smith, GameSpot). Criticisms were uniform: outdated graphics (even for 2000), abysmal character models, sluggish tank controls, excessive backtracking, obtuse puzzles, and a lack of combat depth. The PC version’s game-breaking bugs were a major point of condemnation.

- The Middle Ground: Many conceded that beneath its technical failings lay an interesting, ambitious game with a compelling central idea.

- Commercial Performance & Studio Fate: The game sold poorly. It was a budget title on a dying console (PS1) and a niche PC release. It did not generate enough revenue to save Creative Reality, which closed shortly after its release. It is, in effect, the studio’s swan song—a final, labored cry of creative ambition stifled by circumstance.

- Evolving Reputation & Cult Status: Over two decades, Martian Gothic has undergone a rehabilitation of sorts. It is no longer seen as merely a bad Resident Evil clone, but as a unique, bold, and deeply flawed artifact. Its reputation is sustained by:

- Nostalgia for a Specific Aesthetic: The pre-rendered backgrounds and FMV-era voice acting hold a certain charm for survival horror aficionados.

- The Strength of its Core Idea: The “stay alone, stay alive” mechanic remains a brilliantly tense and rarely replicated concept. Modern discussions often cite it as a “what if” scenario—what if this game had the budget and polish of a Silent Hill?

- MOOD’s Iconic Performance: Fenella Fielding’s performance is repeatedly singled out as a highlight, giving the game a memorable anchor.

- The “So Bad It’s Good” / “So Flawed It’s Fascinating” Phenomenon: Its jankiness (bad controls, blocky models, confusing puzzles) has become part of its lore. It is played and discussed by dedicated horror fans precisely because of its imperfections and the sheer ambition visible beneath them.

- Influence on the Industry: Its direct influence is minimal to none. It did not spawn a genre or series. Its legacy is indirect and cautionary:

- Proof of Concept for Team-Separation Mechanics: While not the first (see Day of the Tentacle), its integration of the “characters must not meet” rule into a tense, real-time 3D survival horror framework was unique. It presaged later games that use separation and coordination as a core stressor (e.g., certain puzzles in The Last of Us Part II).

- A Warning Tale of Scope Creep: It exemplifies the dangers of marrying a complex, puzzle-heavy adventure game structure to the resource-management demands of a survival horror game. The resulting hybrid was often unbalanced and frustrating.

- A Marker of the Genre’s Diversity: It stands as a testament to the wild, experimental period of the early 2000s, where Western studios were actively, if clumsily, attempting to synthesize Japanese horror design with their own sensibilities.

Conclusion: A Flawed Masterpiece of Ambition

Martian Gothic: Unification is an impossible game to score with a simple star rating. It is a structural failure with a narrative triumph. Its gameplay is a constant tightrope walk between clever design (the vac-tube logistics, the Trimorph encounters) and sheer frustration (the backtracking, the tank controls, the obtuse puzzles). Its world is beautifully imagined and grotesquely rendered, with an AI companion whose voice alone elevates the entire experience. Its story is a dense, satisfying sci-fi horror tapestry that would be celebrated in any other medium.

To play Martian Gothic today is to engage in archaeological reconstruction. You must tolerate its technical squalor to uncover the brilliant, broken civilization of ideas beneath. You are not playing a polished product; you are witnessing the palimpsest of a game that was gutted by its own ambitions and a harsh development timeline. The sacrifice of Martin Karne at the end—a moment of selfless heroism—resonates differently when you know that the game itself, and the studio that created it, were also sacrificed to a larger, uncaring system (the market, the hardware limitations, the deadline).

Final Verdict: Martian Gothic: Unification is a cult classic not because it is good, but because it is profoundly, interestingly itself. It is a 6/10 game with a 9/10 story and a 4/10 control scheme. For the historian, it is an essential case study in development hell and genre hybridization. For the player, it is a punishing, atmospheric, and unforgettable journey to a red planet where the real horror is not the zombies, but the game’s own inability to consistently realize its terrifying vision. It is a ghost—a digital specter of a smarter, more ambitious game that might have been, forever haunting the footnotes of survival horror history. To ignore it is to ignore a painful, vital lesson in what happens when creative passion collides with commercial reality. To embrace it is to embrace the beautiful mess of game development itself.