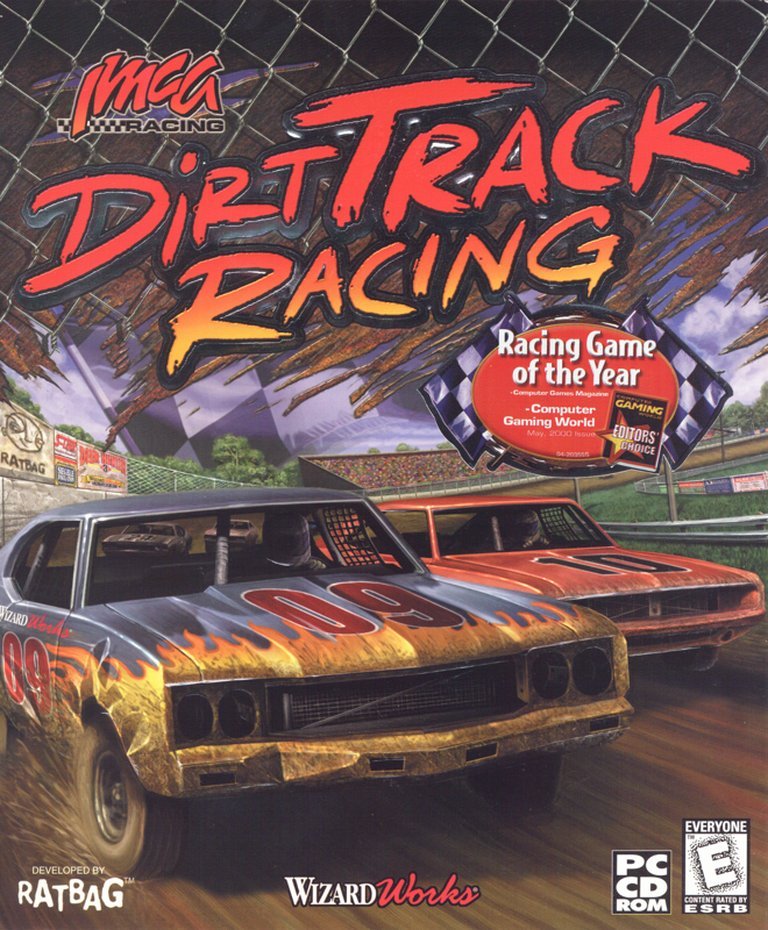

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Ratbag Pty, Ltd., WizardWorks Group, Inc.

- Developer: Ratbag Pty, Ltd.

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 1st-person and 3rd-person

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Car tuning, Damage model, Sponsorship management, Suspension adjustment, Track condition changes

- Setting: Dirt oval tracks, Figure-8 tracks

- Average Score: 68/100

Description

Dirt Track Racing is a racing simulation focused on the thrill of competing on small oval dirt tracks, including figure-8 configurations. Players can engage in single races or a career mode that starts them with basic vehicles, requiring strategic wins to attract sponsors, earn money, and upgrade cars across three classes—stock, pro stock, and late model. The game emphasizes authentic physics with dynamic track conditions, extensive car tuning options for suspension and performance, and supports online multiplayer for up to 10 racers, delivering a gritty and immersive dirt track experience.

Gameplay Videos

Dirt Track Racing Free Download

Dirt Track Racing Cracks & Fixes

Dirt Track Racing Patches & Updates

Dirt Track Racing Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (67/100): Simple to learn, hard to master, but gets monotonous after a while

en.wikipedia.org (69/100): Ratbag proves once again that they are the Kings of racing sims, even the bargain brand.

oldpcgaming.net : By far the most interesting and innovative part of Dirt Track Racing is the career mode.

Dirt Track Racing Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes at the career screen, during name entry, or in the game menu as specified.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| MEGASAXON | Grants $1,000,000 |

| MEGAVEE | Grants $15,000,000 |

| TOOSLOW | AI Cars Don’t Move |

| WILSONDRIFT | Drift for Mini Turbo |

| SUPERHARD | Super Hard Difficulty |

| KOKOBOOSTER | Turbo Mode |

| if_money | Infinite money |

| EAQ79LF4G37DB | All Liveries |

| 25ATEU26BWD0B | All Single Events |

| 9YME5A0H30HEJ | All Tracks |

| R8RNQ7NP6M0DC | Championship |

| 4LAEYR10WLRC5 | Vehicle Set 1 |

| LNBMGDCLPDMF3 | Vehicle Set 2 |

| T0KVTQDLYM38G | Vehicle Set 3 |

Dirt Track Racing: The Unvarnished Soul of Oval Racing

Introduction: The Grit in the Geartrain

In the pantheon of racing video games, where glossy supercars and cinematic crash physics often dominate the conversation, Dirt Track Racing (DTR) stands as a defiant, mud-spattered monument to a more elemental form of motorsport. Released in late 1999 by the now-legendary Australian studio Ratbag Games, this budget-priced ($19.99) simulation of short-track, grassroots stock car racing was not merely another entry in a crowded genre; it was a deliberate, almost anthropological, dive into the raw, unglamorous heart of American “circle track” racing. At a time when the industry was enamored with the spectacle of Need for Speed and the precision of F1 simulations, DTR asked a radical question: what if the thrill wasn’t in the exotic machinery or the global stage, but in the visceral, tactile negotiation of a 500-horsepower brute on a loose, evolving dirt surface? My thesis is this: Dirt Track Racing is not just a competent budget racer; it is a historically significant, deeply authentic simulation that sacrificed graphical grandeur for an unprecedented level of mechanical and situational depth, capturing a niche motorsport with a fidelity that outright baffled its contemporaneous critics and laid foundational design philosophy for the “destruction racing” genre that would follow. Its legacy is one of proud, gritty specialization.

Development History & Context: Ratbag’s “Budget” Philosophy

The Studio and its Predecessor: To understand DTR, one must understand Ratbag Games. This Adelaide-based studio, founded by Greg Siegele and Jeffrey Lim, burst onto the scene in 1998 with Powerslide. That game was a revelation—a futuristic, anti-gravity racer renowned for its revolutionary “Difference Engine” physics system that allowed for breathtaking, realistic slides. The same core technology, with significant tweaks, was repurposed for DTR. The developers’ vision, as stated in interviews and evident in the design, was to move from the apocalyptic arenas of Powerslide to the “real-world grime” of American short tracks. They weren’t aiming for the mainstream; they were targeting the obsessive, tuner-oriented mindset of actual dirt track enthusiasts.

Technological Constraints and Ingenuity: Released in late 1999, DTR was a Direct3D and Glide title built for the Pentium II era. Its system requirements were modest (PII 233MHz, 32MB RAM), a necessity for its budget pricing and broad accessibility. The “Difference Engine” was the star, simulating not just car dynamics but track evolution. The graphics, while smooth and functional, were intentionally unpretentious. Cars were blocky but recognizable as modified 60s/70s muscle cars (with fictional names like “Hammerhead” for a Barracuda). Tracks were sparse—a few grandstands, some billboards, and vast expanses of brown. This was not a flaw but a design choice; resources were poured into physics and AI, not polygon counts. The game famously included a “software renderer” for those without 3D accelerators, a vital feature for accessibility that also resulted in the famously drab, chunky visual style noted by critics like PC Joker and GameStar.

The Gaming Landscape of 1999: The racing genre was bifurcated. On one side were arcade racers like Need for Speed: High Stakes (1999) and Test Drive Le Mans (1999), emphasizing speed, glamour, and exotic locales. On the other were hardcore simulations like Gran Turismo (1997) and F1 99 (1998), focused on tarmac precision and car collecting. DTR carved out a third, almost non-existent path: the specialized, mechanical, “blue-collar” simulation. Its competition was sparse—perhaps NASCAR Racing (1994) or IRacing‘s early concepts—but those were more about ovals with higher production values. DTR’s true competitor was the real-world hobby it simulated, and in that arena, it was peerless.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of “Joe Fields, the Grocer from Iowa”

DTR possesses no traditional plot, cutscenes, or voice acting. Its narrative is emergent, systemic, and entirely player-driven—a pure “sandbox story” in the truest sense. The game’s thematic core is the democratization of racing glory.

-

The Ladder of Realism: The narrative begins not with a backstory but with a stark financial reality: $1,000 and a junkyard car. You are not a prodigy, a spy, or a street racer. You are an everyman (or everywoman) with a dream and a clunker. The career mode is a classicrags-to-riches progression, but it’s uniquely grounded. You don’t “unlock” legendary tracks; you earn the right to race at slightly bigger local ovals. You don’t collect hypercars; you move from a banged-up Stock class car to a Pro Stock, and finally to a souped-up Late Model. The rivalries are with “Joe Fields, a grocer from Iowa, or Walter Cunningham, a barber from Minnesota,” as IGN poetically put it. The story is the slow burn of local heroism.

-

Sponsorship as Plot Momentum: The most brilliant narrative device is the sponsorship system. After each race, you receive offers based on your performance. Do you take the small, immediate cash injection from a local diner sponsor, locking you into a multi-race contract? Or do you gamble, reject the offer, and hope for a bigger payout and a national brand after the next big win? This isn’t just an economic mechanic; it’s a drama of patience versus ambition, mirroring the real financial gambles of semi-pro racing. The “plot” of your career is written in thesecontractual decisions.

-

The Car as a Character: Your vehicle is your avatar and your narrative arc. It begins as a beaten, patched-up chassis. Through tuning—adjusting toe, camber, spring rates, weight distribution—you are not just optimizing numbers; you are sculpting the car’s personality to match a specific track’s demands. A car set up for a short, tight figure-8 will handle completely differently on a long, sweeping oval. The narrative of a successful race weekend is the story of you, the crew chief and driver, deciphering the track’s “character” (dry and dusty, tacky and moist) and convincing your car to cooperate. Failures are narrative too: an engine blow on the last lap, a bent chassis from “trading paint,” a botched setup leading to constant spinouts. These are the tragedies and comedies of grassroots racing.

-

The Absence of Grandeur: The themes are work ethic, mechanical empathy, and local pride. There are no world championships, only the “series” at a particular track. The glory is a $5,000 purse and a trophy that might sit on a shelf next to a family photo. This thematic restraint—the complete lack of Hollywood gloss—is DTR’s most powerful storytelling choice. It validates the real-world sport’s ethos, making the player feel like an authentic insider, not a tourist.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Where the Mud Hits the Chassis

DTR’s genius is not in what it adds, but in the ruthless, detailed depth of its core systems.

-

The Physics Loop – The Difference Engine, Refined: As IGN noted, Ratbag “tightened up” the Powerslide physics for DTR. The cornerstone is the simulation of weight transfer, tire slip, and, most critically, surface variability. Dirt is not a single surface. A dry, dusty track has a thin layer of loose sediment, causing constant micro-slides. A “tacky” or moist track offers more mechanical grip. Crucially, the track evolves during the race (“The track will dry out as more and more cars drive through”). The racing line becomes a polished, faster groove, while the outside remains loose. This creates a dynamic, strategic racing line: run low early to build a buffer, or gamble on the high groove later. Mastering this requires sensing the car’s balance through the force feedback wheel or the subtle visual cues of the camera.

-

Tuning – The Engineering Simulator: This is the game’s soul. Accessible via the garage between races, the tuning menu is a gearhead’s paradise (or nightmare). Options include:

- Suspension: Bump/Rebound dampening, spring strength, travel.

- Geometry: Toe-in/Toe-out, camber, wheel offset.

- Brakes: Strength bias (front/rear).

- Gearing: Individual gear ratios.

- Weight Distribution: Ballast placement.

- Tires: Compound choice (affecting wear and grip).

Every change has a non-linear, interconnected effect. Stiffer rear springs might improve corner exit but make the car bouncy on bumps. More negative camber improves cornering grip but increases tire wear. As the player review astutely noted, “Most of the ‘fun’ in DTR is car tuning… you may need a degree in automotive engineering.” This transforms gameplay from单纯的 driving into a holistic management sim.

-

Damage & Consequence: Contact is heavily penalized. “Brute force do NOT work here,” the player review states. Minor “trading paint” incurs repair costs that eat into winnings. Serious contact visibly bends bodywork (a nice visual touch) and, more importantly, alters handling (a bent wheel, misaligned suspension). This creates a profound risk-reward dynamic: is it worth a high-risk pass for one position when it could cost $2,000 in repairs and ruin your championship chances? The damage model is not Hollywood spectacular but mechanically consequential.

-

AI & Difficulty – The Scalable Opponent: DTR’s AI system was revolutionary for its time. Instead of Easy/Medium/Hard, you could set a percentage-based skill level (e.g., 85% challenge). This allowed for incredibly granular skill calibration. The AI was praised for being “a challenge without being impossible,” exhibiting realistic mistakes and aggression. Their performance also affected track evolution—a full field of AI cars will “rubber in” the track just like humans.

-

Career Mode – The Strategic Core: This is where all systems converge. Starting with $1,000, you buy a Stock-class beater (no upgrades allowed, only repairs). You enter low-payout “series” at small tracks. Success unlocks Pro Stock (with tuning) and Late Model (extensive tuning) classes, bigger tracks, and larger purses. The strategic layer of sponsorship contracts—balancing immediate cash versus long-term potential—adds a compelling metagame. It’s a slow, deliberate climb that makes every dollar and every point feel earned.

-

The Flaw – Repetition by Design: The most consistent criticism is the intrinsic repetitiveness of oval racing. As GameSpot wrote, it’s “hard to overlook its repetitive tracks and racing events.” You are, quite literally, going round and round. The figure-8 tracks offer a brief, chaotic novelty, but the core loop is relentless左转. The game’s greatest strength—its obsessive simulation of a specific, narrow motorsport—is also its primary barrier to mass appeal. This isn’t a bug; it’s a feature of the source material.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Beauty of the Basic

DTR’s aesthetic is a masterclass in “environmental storytelling” through minimalism.

-

Visuals & Atmosphere: The graphics are deliberately unpolished. Cars look like they’ve been painted with a roller. Tracks are flat, textured planes with simplistic billboards for local businesses (a key narrative touch). The sky is a simple gradient. There is no “chrome,” no lens flares, no particle effects for exhaust smoke that obscures vision. Yet, this ugliness is profound. When you see your car caked in mud, or a dust cloud billowing behind the pack, or the way the setting sun casts long shadows across the empty infield, it feels authentic to the setting. This is not a televised, sponsor-saturated NASCAR Cup race; this is a Saturday night under the lights at the local county fairgrounds. The choice of time of day (dawn, day, dusk, night) for races, combined with the simple, effective lighting, creates a powerful, recurring atmosphere of regional, community-based racing.

-

Sound Design – The Roar of the Simple Life: The sound design is similarly focused. The engine note is a deep, guttural roar that changes pitch with RPMs. There is the crunch of dirt being displaced, the thwack of a minor collision, the scrape of metal on metal in a serious wreck. Criticisms of a “monotonous engine noise” miss the point: in a field of nearly identical V8-powered stock cars, the sound should be a uniform, deafening wall of noise. The audio is functional and immersive, grounding you in the cockpit. The lack of a dynamic soundtrack (no licensed rock music) reinforces the game’s commitment to diegetic, on-track sound.

-

The UI & Presentation: The menus are utilitarian, text-based. The garage interface is a spreadsheet of numbers. This reinforces the theme: this is a working man’s simulator, not an entertainment product. There is no fluff, only data. This design philosophy extends to the complete lack of “cinematic” presentation between races. No replay editors, no award ceremonies. Just the results screen and the next race’s entry list.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Dirt

Critical Reception at Launch (1999-2000): DTR’s reviews were a stark dichotomy, perfectly illustrating its niche appeal.

* The Enthusiasts (USA): Computer Gaming World (90%) and IGN (88%) were effusive. CGW called it “bedlam on wheels” and praised the career mode and multiplayer. IGN’s Tal Blevins declared it “the best title I’ve ever played that was originally released for under $20, in any genre,” lauding its “exquisite visuals” (within context) and “outstanding real-world physics.” They saw the forest for the trees: an unparalleled simulation of a specific experience.

* The Skeptics (Europe & Mainstream): German magazines (PC Player 56%, PC Action 63%) were notably cooler, finding the tracks “monotonous” and the graphics “old-hat.” GameSpot (66%) summarized the divide: “Even with all of Dirt Track Racing’s finer points, it’s hard to overlook its repetitive tracks and racing events.” Adrenaline Vault (50%) conceded its “outstanding real-world physics” but stated the “sameness of the overall experience will not hold the attention of anyone but diehards.” The critical consensus was: an exceptionally deep and authentic simulation utterly hamstrung by the repetitive nature of its subject matter.

Commercial Performance & Cult Status: As a WizardWorks budget title, DTR was not a blockbuster. Its sales figures were modest. However, it found its audience. The “diehards”—fans of actual IMCA/USAC short-track racing—embraced it as the first faithful digital representation of their sport. Online communities (via the included GameSpy Lite integration) formed around shared tuning secrets and league racing. Its cult status was cemented by its sequels (Dirt Track Racing: Sprint Cars, Dirt Track Racing 2, Dirt Track Racing: Australia) and its inclusion in the permanent collection of the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), an honor that recognizes its cultural and historical significance in Australia’s game development legacy.

Influence on the Industry: DTR’s influence is subtle but profound.

1. The “Ratbag” School of Physics: Its successor studio, Ratbag Games Australia (after a corporate shift), produced Leadfoot: Stadium Off-Road Racing (2001) and the unreleased Dirt Track Racing 3. The lineage is clear. More importantly, its philosophy of accessible, deep, simulation-first physics for a budget price influenced later Australian studios like Team Bondi (L.A. Noire) and, indirectly, the flat-out style of racing chaos popularized by Bugbear Entertainment (FlatOut series, 2004 onward). While FlatOut added arcade destruction, its core loop of “dirt track racing with physics-driven mayhem” owes a clear debt to DTR’s foundational work on sliding and contact consequences.

2. Niche Simulation Viability: It proved a market existed for hyper-specific, mechanically deep simulations outside the F1/Rally/GT trifecta. Games like rFactor 2‘s oval content or NASCAR Heat‘s career modes stand on the shoulders of DTR’s insistence that tuning, track evolution, and financial management were as important as the drive.

3. The “Budget Depth” Paradigm: IGN’s claim that it outshone $50 titles was a harbinger of the “budget gem” phenomenon. It demonstrated that development resources, if allocated to core systems instead of polish, could yield a more satisfying experience for a dedicated player base.

Conclusion: Imperfect, Essential, and Enduring

Dirt Track Racing is not a perfect game. Its visual austerity is off-putting to the uninitiated. Its tracks, by definition, are monotonous loops. Its user interfaces are raw. For the average gamer seeking thrills, it is a frustrating, repetitive slog.

But for the historian and the connoisseur, it is a masterpiece of focused design. It is a game that understands its subject—the gritty, strategic, mechanically obsessive world of local stock car racing—and refuses to compromise on its simulation. Every system, from the granular suspension tuning to the evolving track surface to the percentage-based AI, serves the singular goal of making you feel like a real driver in a real racer’s garage. Its legacy is not in sales charts or Game of the Year awards (though it won Computer Games Strategy Plus‘s 1999 Racing Game of the Year over more famous titles), but in its pure, unadulterated authenticity. It is the video game equivalent of a well-worn, high-horsepower sprint car: ugly, loud, brutally difficult to master, and utterly without pretense. Dirt Track Racing did not just simulate dirt track racing; it celebrated its every tedious, strategic, muddy detail. In doing so, it carved its own indelible groove in the history of racing games—a groove that, like the fastest line on a drying clay oval, remains the path of least resistance for anyone seeking the unvarnished soul of the sport.

Final Verdict: A niche, historically vital simulation. Flawed in presentation, revolutionary in depth. 8.5/10 as a Racing Simulator, 6.0/10 as a casual arcade racer. Its place in history is secure: the definitive, unapologetic love letter to the local dirt track.