- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Sierra On-Line, Inc.

- Developer: Sierra On-Line, Inc.

- Genre: Puzzle, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Cards, Tile matching puzzle, Tiles

Description

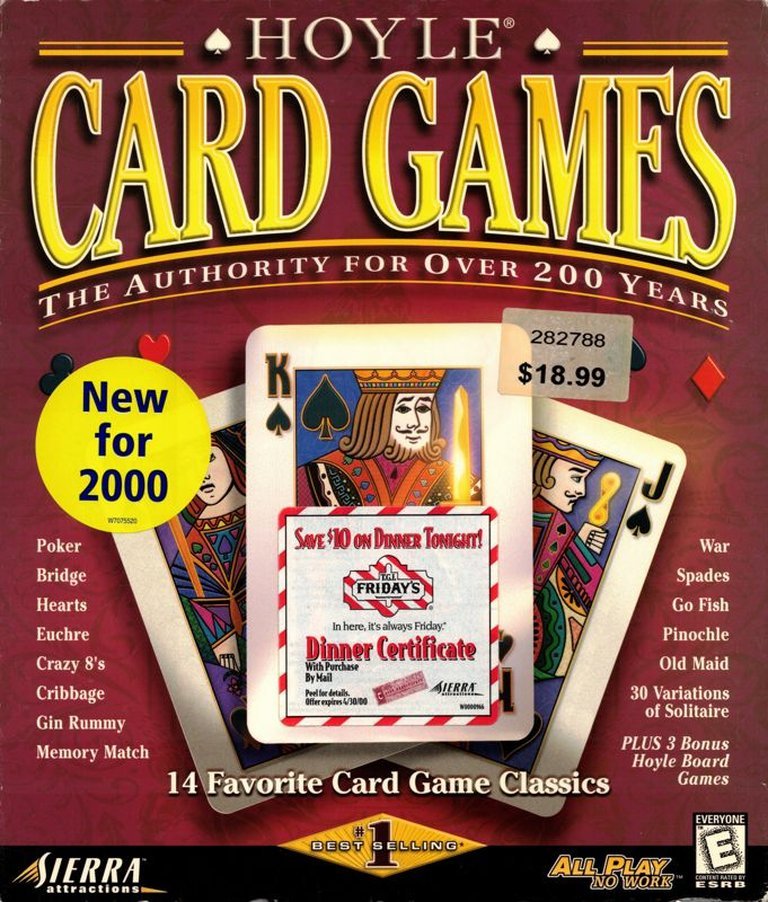

Hoyle Card Games is a 1999 video game compilation that brings together fourteen classic card games, such as poker, bridge, hearts, euchre, and thirty variations of solitaire, in a whimsical virtual setting. Players compete against quirky AI opponents including aliens, cardsharks, and a French puppet character, with top-down gameplay, point-and-select interface, and options for single-player or head-to-head multiplayer via internet.

Gameplay Videos

Hoyle Card Games Free Download

Hoyle Card Games Cheats & Codes

Game Boy Color

Codes are for use with GameShark or Pro Action Replay devices on the North American (NTSC) version.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 01ff29d6 | Plenty of Cash |

| 015f2ad6 | Plenty of Cash |

Hoyle Card Games (1999): The Digital Preservation of a Paper Legacy

In the quiet, pre-internet suburban den of the late 1990s, a stack of well-worn cards and a scored cribbage board might sit beside a beige tower PC. The bridge between these two worlds—the tactile, social ritual of tabletop games and the solitary, pixelated glow of the monitor—was often paved by Sierra On-Line’s Hoyle series. The 1999 Windows/Macintosh release, Hoyle Card Games, stands not as a revolutionary title but as a monumental, if imperfect, curator. It was the decade’s definitive digital compendium for a vast pantheon of classic card games, tasked with a singular, profound mission: to encode the 250-year-authoritative “according to Hoyle” into the universal language of CD-ROM. Its legacy is a tapestry of charming innovation, frustrating limitation, and the quiet, essential work of digital preservation.

1. Introduction: A Bridge Across Centuries

The thesis of Hoyle Card Games (1999) is deceptively simple: provide authentic, accessible simulations of the world’s most beloved card games. Yet, this goal sits at the complex intersection of pedagogy, entertainment, and technological transition. The game is less a “game” in the traditional sense of narrative-driven challenge and more an interactive reference library, a tool for play. It represents the last gasps of Sierra On-Line’s classic Hoyle’s Official Book of Games lineage before the brand’s dilution into yearly, budget-priced compilations under new management. This review argues that Hoyle Card Games (1999) is a pivotal,dual-natured artifact: it successfully democratized a vast corpus of game rules for a generation raised on PCs, but its execution was hamstrung by its own heritage, technical constraints of the era, and a fundamental misunderstanding of its potential audience’s desires for connected, contextual play.

2. Development History & Context: The Sierra Spirit in a Shrinking Universe

The Studio and the Vision: The 1999 Hoyle Card Games was developed by Sierra On-Line, Inc., the same studio that launched the series with Volume 1 in 1989. By 1999, Sierra was a ghost of its former adventure-game glory, having been gutted by the 1998 merger of its parent company, CUC International, with HFS (which became part of AOL) and the subsequent acquisition by Havas (Vivendi Universal). The development team, credited with 52 individuals, was working within a established franchise formula, not pioneering a new one. The “creator’s vision” here was one of iteration and compilation: take the existing Sierra Hoyle engine, update the interface for Windows/Mac, expand the game list to a competitive number (14), and add a novel “Face Maker” tool—a clear nod to the burgeoning customization culture of the late ’90s.

Technological Constraints & Gaming Landscape: The game was a CD-ROM product for Windows (and Macintosh), requiring a mouse. This places it in the mature phase of the PC gaming “multimedia” boom. The core engine was a relic—a top-down, point-and-select interface built on decades-old Sierra Creative Interpreter (SCI) technology originally designed for text adventures. This is evident in the game’s genres listed on MobyGames: “Puzzle” and “Strategy / tactics” with a “Top-down” perspective. The constraints were not just graphical (using sprite-based cards and opponents rather than 3D tables) but philosophical: the game was designed for a now-fading “edutainment” and family PC market, where a single title could be a digital recreation room. It competed not with StarCraft or Half-Life, but with Microsoft Solitaire Collection and physical card decks. Its primary innovation was not in gameplay simulation technology but in brand aggregation and character presentation.

The Hoyle Brand’s Journey: As detailed in the Wikipedia “Hoyle’s Official Book of Games” article, the series began as an attempt to faithfully license the rules of Edmond Hoyle, the 18th-century authority whose name became synonymous with “official rules.” Early Sierra volumes (1989-1991) were celebrated for their crossover characters from Sierra’s adventure games (King’s Quest, Space Quest, Leisure Suit Larry) acting as opponents with personality. By the mid-1990s, under Sierra, the series became an annualized franchise with dozens of themed spin-offs (Hoyle Casino, Hoyle Board Games). The 1999 Hoyle Card Games was a mainline entry in this crowded field, a “Greatest Hits” style package aimed at consolidating the card game sub-franchise. Just three years later, Sierra would be shuttered, and the Hoyle license would pass to Encore Software, shifting the series toward budget re-releases and casino-focused titles, marking the end of an era this 1999 version represented.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of “According to Hoyle”

This section requires a non-literal interpretation of “narrative,” as the game has no plot. Its story is one of authority, nostalgia, and accessibility.

-

The Authority Narrative: The entire package is a tribute to Edmond Hoyle’s posthumous authority. Every rule, from the scoring of a Bridge contract to the stock limit in Pyramid Solitaire, is presented as absolute, derived from the “official book.” This transforms the game from a mere collection into a digital codex. It performs a cultural preservation act, taking rules that existed in dusty books and oral tradition and embedding them in a standardized, unchanging digital format. The theme is one of truth and standardization—there is one correct way to play, and Hoyle Card Games is its keeper.

-

The Nostalgia Narrative (The Sierraverse): For players who grew up with Sierra’s adventure games, the opponent characters are the game’s soul. As the Wikipedia article notes, the series tradition was to populate the table with avatars like King Graham, Larry Laffer, and Roger Wilco. Each came with a personality, idle banter, and reactions. In this 1999 version, the “aliens, cardsharks or even a French guy with a puppet” mentioned in the official description are a continuation of this tradition—a cast of quirky, often humorous personas that turn a sterile simulation into a social encounter. The narrative here is crossover and familiarity. You weren’t just playing against “AI”; you were getting taunted by a Leisure Suit Larry clone or receiving a cosmic, space-saving urgency from Roger Wilco. This layer provided a contextual, almost diegetic, story to each match: “Can I beat the smugness out of Larry Laffer at Gin Rummy?”

-

The Accessibility Narrative: The underlying, unstated theme is democratization. Complex games like Contract Bridge, Pinochle, and Euchre, with their dense bidding systems and scoring, were made approachable through in-game tutorials and rule glossaries (as noted in the MacGamer’s Ledge review). The game posits that no one needs a human teacher or a physical rulebook anymore. The “story” of each play session is the player’s own journey from novice to confident player, guided by the game’s didactic interface. This is the educational promise of the Hoyle brand, fully realized in a format that requires no social pressure or external resources.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Catalogue of Competence

Core Loop & offerings: The game presents a central lobby from which the player selects one of fourteen card games: War, Poker (likely a basic Five-Card Draw variant, not Texas Hold’em), Bridge, Hearts, Euchre, Crazy 8’s, Cribbage, Gin Rummy, 30 types of Solitaire (though the description says “30 types,” the MobyGames categorization focuses on standard solitaire/patience), Spades, Go Fish, Pinochle, Old Maid, and Memory (Concentration). The loop is: select game -> select opponent(s) or solitaire variant -> play via point-and-click interface -> receive post-game stats/feedback.

AI and Opponent Systems: The AI is the game’s most discussed and divisive element.

* Character-Driven AI: Opponents from the Sierra cast (and new creations) have predefined, static difficulty levels (likely Beginner, Intermediate, Expert as per series tradition) and distinct personalities expressed through text dialogue and, in some versions, speech. Their “strategy” is based on rule-based logic, not machine learning. This leads to predictable patterns in complex games like Bridge or Poker, a point criticized in contemporary reviews. The MacGamer’s Ledge review specifically criticized the “poor explanation of the rules” and “lack of variety in Poker,” implying the AI’s limited repertoire made it stale quickly.

* The Head-to-Head Anomaly: A notable and bizarre design choice, highlighted by MacGamer’s Ledge, was that War—a game of pure chance with zero player agency—was the only competitive game granted a true “head-to-head” mode where two humans could play directly against each other on the same machine (hot-seat). Meanwhile, skill-based games like Poker or Bridge were restricted to play against the AI. This was a profound failure to understand the social dynamics of card gaming, where human bluffing and bidding are the entire point.

User Interface & Innovations: The UI is a classic 1990s CD-ROM interface: often cluttered, reliant on nested menus, but functional. The standout innovation, praised by FamilyPC Magazine (88%), was the Face Maker. This tool allowed players to create custom avatars, a form of personalization that was novel for the genre and a direct appeal to the era’s growing interest in user-generated content. It was “so much fun to use,” according to FamilyPC, that it could distract from the core card gameplay—a telling critique that the game’s ancillary features outshone its primary function for some.

Flawed Systems: The most significant systemic flaw was rule fidelity vs. AI competence. The Wikipedia article notes that early volumes were criticized for deviations from official Hoyle rules (e.g., Cribbage scoring in Volume 1). While the 1999 version likely corrected these, the MacGamer’s Ledge review suggests rule explanations for some games were still “poor.” You could have a perfect rule set but an AI that played sub-optimally or illogically, which breaks the educational promise. Furthermore, the game’s lack of Internet multiplayer (despite MobyGames listing “Internet” under multiplayer options for the Windows version, this likely refers to LAN or null-modem play, not online services) was a major limitation in 1999, when Diablo II and Ultima Online were establishing online norms. For a social game, being confined to local hot-seat or AI play felt isolating.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Sierra Aesthetic in Miniature

Visual Direction & Artwork: The game’s world is the green-felt virtual table. The art, credited to Rabih AbouJaoudé, Julian Glover, and others, is functional and period-appropriate. Cards use a standard, legible design (likely licensed from Brown & Bigelow, as the series historically did). The “world-building” is entirely delegated to the opponent character sprites and animations. These are not just portraits; they are tiny, expressive avatars that sit at the table, react to plays (with delight or frustration), and lean forward when making a move. This is where Sierra’s adventure-game heritage bleeds in, creating a consistent, if low-detail, “Sierraverse” atmosphere. The screenshots show a clean, top-down interface with a muted color palette typical of late-’90s casual games. 3D modelling (by Max Braun) was likely used for minor table effects or card animations, but the core is 2D sprite work. The aesthetic is one of friendly, unthreatening digital domesticity.

Sound Design & Music: Sound, handled by Mike Caviezel, and music by Evan Schiller, follow the period’s CD-ROM standards. The inclusion of digitized speech for character reactions (a feature expanded since the early 1990s Hoyle Classic Card Games) is a critical atmospheric element. The sound of cards shuffling, being dealt, and played is functional. The music is likely light, unobtrusive, MIDI-based tracks meant to fade into the background. The sound design’s goal is not immersion in a fantasy world but reinforcement of the game’s tactile, tabletop simulation—the clink of chips (if used), the slap of a card down, the character’s voice quip. It’s serviceable, not memorable, adhering to the “background ambiance” school of design for casual titles.

Contribution to Experience: Together, these elements create a cohesive, if bland, identity. The art and sound do not simulate a glittering casino or a smoky backroom; they simulate a well-lit, polite family rec room. The Sierra characters provide all the personality, turning the abstract act of matching cards or playing Bridge into a series of vignettes with familiar, joke-cracking personalities. This successfully lowers the intimidation factor of complex games but also prevents the experience from feeling majestic or deeply atmospheric. It’s a world defined by its avatars, not its environment.

6. Reception & Legacy: A Mixed Bag from the Start

Critical Reception at Launch: The critical consensus, as aggregated on MobyGames, was positive but lukewarm (84% from 3 critics). Reviews were mixed on what fundamentally constituted a “good” Hoyle game.

* Praises: The breadth of games (14 card games, plus 30 solitaires), the faithful rule sets, the charming and funny character animations/voicing, and the sheer utility as a digital card room were consistently noted. FamilyPC’s 88% review highlights the Face Maker as a killer app. The series’ educational value was a recurring strength.

* Criticisms: The criticisms were equally consistent and severe:

1. AI Depth: Predictable, basic AI in complex games (Bridge, Poker).

2. Rule Explanations: Inadequate tutorials for some games (MacGamer’s Ledge).

3. Head-to-Head Design: The baffling choice to only allow hot-seat play for War, not for more social games.

4. Performance: A legacy issue from the series’ inception; the SCI engine was often slow, even on period hardware.

5. Lack of Online Play: A glaring omission in the dawn of the online gaming age.

Computer Gaming World’s pan of the early volumes called the non-character-focused games “really children’s games” and criticized rule deviations—a sentiment of “diluted quality” that clung to the series.

Commercial Performance & Evolution: The series was a consistent, mid-tier seller for Sierra through the 1990s, capitalizing on the “multimedia PC” boom. The 1999 version was part of this profitable, if unspectacular, line. The true decline began post-Sierra. As the Wikipedia timeline shows, after Sierra’s closure (circa 2008), the license passed to Encore Software. Subsequent titles like Hoyle Card Games 2005 and Hoyle Official Card Games Collection (2015) were criticized for becoming generic, low-effort budget compilations with simplified graphics and AI, losing the Sierra character charm. The 2016 finale was a quiet flop. The series’ reputation shifted from “charming authentic simulator” to “cheap, dated cash-grab.”

Cultural Impact & Modern Legacy:

* Preservation: The Hoyle series’ greatest lasting impact is as a digital curator of traditional game rules. For many, these games were their first exposure to the formal rules of Bridge, Euchre, or complex Solitaire variants. The ScummVM project’s support for early Hoyle titles (as mentioned in the Wikipedia article) ensures that the Sierra-era versions with their character charm remain playable on modern systems—a crucial act of preservation.

* The Sierra Crossover: The use of adventure game characters as opponents was a uniquely Sierra phenomenon. It created a shared, playful universe that reinforced brand loyalty. This concept of “crossover cameos” would later be seen in more integrated ways in games like Crawl or the Super Smash Bros. series, but Hoyle was an early, simple example.

* The Template for Casual Compilations: The game solidified the template for the “1001 Games!” casual compilation: a vast list of games with shallow implementation. This model would be endlessly copied by publishers like Encore, EA’s Hasbro collection, and countless Steam bundles. Hoyle Card Games (1999) is a crucial ancestor of that now-ubiquitous, often-detested genre.

* A Relic of a Specific Time: It is a snapshot of a moment when PC gaming was still deeply intertwined with a “software library” mindset. You didn’t go to an app store for a specific game; you bought a “Card Games” CD that had everything. Its failure to adapt to online social play and its increasingly generic successors mark the end of that model.

7. Conclusion: A Flawed cornerstone

Hoyle Card Games (1999) is not a great game by any conventional metric. Its AI is shallow, its design choices are baffling (War for head-to-head), its presentation is dated, and its thematic core is education, not excitement. Yet, to dismiss it is to ignore its quiet, monumental achievement. It was the most comprehensive, officially-sanctioned digital implementation of classic card games of its era. It carried the torch of Edmond Hoyle’s authority into the digital age, using the charisma of Sierra’s adventure icons to make intimidating games like Bridge feel approachable.

Its definitive verdict in history is as a transitional fossil. It represents the last breath of the Sierra-era Hoyle—a series with personality, ambition, and a clear lineage—before the brand was commodified into oblivion. The 1999 release captures the tension at the end of the 20th century: the desire to preserve and digitize analog pastimes clashing with the nascent demands for online connectivity and sophisticated AI. It succeeded brilliantly in the former and failed utterly in the latter. For the historian, it is invaluable: a perfectly preserved artifact of a bygone software philosophy. For the player in 1999, it was a useful, frustrating, and often charmingly personality-filled digital card table. For the series, it was the last coherent stand before the long, slow fade into generic compilation oblivion. Its legacy is not one of awe, but of essential, if imperfect, stewardship.