- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Browser, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: RealRailway

- Developer: RealRailway

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Driving, Stopping, Timing

- Setting: Japan, Urban

Description

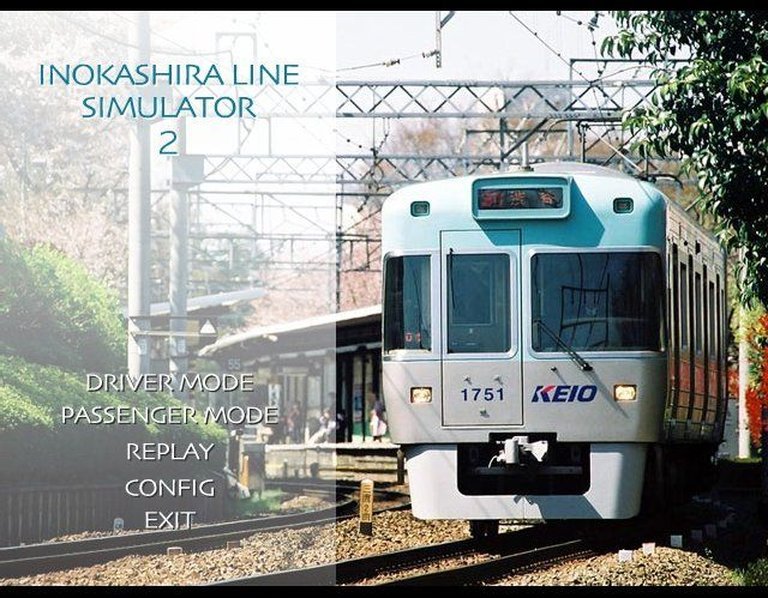

Inokashira Line Simulator 2 is a train driving simulation game set on the Keiō Inokashira Line in Japan, where players take on the role of a commuter train operator navigating between Eifukuchō and Kugayama stations. Presented as a series of flash-based segments for each station interval, the game requires careful speed control to ensure on-time arrivals and stops within designated zones, with performance evaluated based on driving time, stop accuracy, and passenger comfort, and failures like lateness or overshooting resulting in game over.

Gameplay Videos

Inokashira Line Simulator 2: A Minimalist Masterpiece in Niche Simulation

In an era dominated by sprawling open worlds and cinematic narratives, Inokashira Line Simulator 2 emerges as a quiet yet profound counterpoint—a game that strips away all extraneous elements to focus on the pure, unadorned essence of simulation. Released in 2005 by the enigmatic studio RealRailway, this Flash-based title tasked players with operating a commuter train on Tokyo’s Keiō Inokashira Line, emphasizing punctuality, precision, and the understated rhythm of urban transit. While it may have languished in obscurity compared to blockbuster titles, its deliberate design and historical context make it an indispensable study for understanding the evolution of simulation games and the power of minimalist game design. This review will argue that Inokashira Line Simulator 2 is not merely a relic but a intentional artifact that captures a specific moment in gaming history where accessibility and authenticity converged to create a uniquely disciplined experience.

Development History & Context

RealRailway, the sole developer and publisher of Inokashira Line Simulator 2, operated with a visibly low profile, leaving little digital footprint beyond this and related titles. The studio’s vision was clear: to simulate a single, real-world train route with exhaustive accuracy, targeting railway enthusiasts and commuters familiar with the Keiō Inokashira Line. This approach reflected a broader trend in early-2000s simulation development, where small teams or even solo developers leveraged niche interests to build dedicated communities. The game’s existence as a follow-up to Keio Line Simulator 2 (2001) suggests a deliberate project to document multiple Japanese rail lines, though RealRailway’s broader catalog remains sparsely documented.

Technologically, the game was constrained by the mid-2000s Flash ecosystem. In 2005, Flash was the dominant platform for browser-based games, prized for its cross-platform compatibility (supporting Windows, Macintosh, and web browsers) but limited by its computational power and graphical capabilities. Inokashira Line Simulator 2 was structured as five discrete Flash movies—one for each inter-station segment—a clever workaround to manage performance and loading times within Flash’s environment. This segmentation, while technically pragmatic, also naturally broke the journey into manageable chunks, aligning with the game’s focus on discrete, repeatable trips. The gaming landscape of 2005 was seeing a rise in specialized simulators, from Microsoft Flight Simulator to early train simulators like RailWorks, but most demanded high-end hardware. In contrast, Inokashira Line Simulator 2’s freeware, browser-based model democratized access, inviting anyone with an internet connection to experience rail simulation without financial or technical barriers. This context highlights how indie developers used Flash to carve out niche markets, prioritizing specificity over mass appeal.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Inokashira Line Simulator 2 eschews traditional narrative structures entirely. There is no plot, no characters, and no dialogue—the player assumes the role of an anonymous train driver tasked with a routine commute. Yet, within this vacuum, the game constructs a rich thematic landscape through its mechanics alone. The absence of story forces attention onto the act of driving itself, transforming mundane transit into a meditative ritual.

The primary theme is professional responsibility and punctuality. The game’s core challenge—arriving at each station on time—mirrors the real-world pressure on commuter rail operators to maintain strict schedules. Failure results in immediate “game over,” simulating the high-stakes consequences of delays in urban transit. This mechanic instills asense of duty, where every second counts and precision is non-negotiable.

Secondly, the game explores the beauty of routine and rhythm. The route between Eifukuchō and Kugayama is fixed and repetitive, echoing the daily grind of public transport workers. Success is measured not in epic victories but in flawless repetition, celebrating the quiet mastery of a craft. This resonates with broader cultural appreciations of ikigai (purpose) in Japanese work ethic, though the game presents it universally.

Thirdly, isolation and focus are implicit themes. The first-person perspective confines the view to the cab and tracks, eliminating distractions. The player is alone with the controls, embodying the solitary concentration required of train operators. This creates a palpable atmosphere of tension and tranquility simultaneously—a paradox at the heart of simulation.

Finally, urban infrastructure as character emerges through the setting. The Keiō Inokashira Line is a realarter of Tokyo, and its simulation grounds the game in a specific geographic and cultural context. While not explicitly narrative, the route’s authenticity—from station names to track layouts—invites players to engage with Tokyo’s transit geography, making the city itself a silent protagonist.

These themes are not told but experienced, a testament to the game’s design philosophy where gameplay is the sole vehicle for meaning.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Inokashira Line Simulator 2 revolves around a deceptively simple loop: accelerate or brake the train to travel between stations, ensuring arrival on schedule and a stop within a designated zone. This loop is repeated for five segments across the route, each corresponding to a stretch between consecutive stations. The interface displays time and remaining distance to the next station on the right side of the screen, providing critical data for decision-making. The challenge lies in balancing speed against precision—too fast, and you overshoot; too slow, and you delay.

The evaluation system post-trip is the game’s only form of progression. Players receive scores on three criteria:

– Driving time: Adherence to the timetable, rewarding efficient yet controlled operation.

– Stop position: Accuracy in halting within the marked zone, requiring fine-tuned braking.

– Comfort level: Likely inferred from the smoothness of acceleration and braking, simulating passenger experience—a subtle nod to real-world rail operations where jerkiness affects rider satisfaction.

This triad creates a holistic assessment, blending technical skill with empathetic simulation. However, the game lacks traditional progression systems: no unlocks, no difficulty scaling beyond personal mastery, and no narrative arcs. The satisfaction comes from internal improvement, not external rewards.

Innovative aspects include its segmented Flash architecture. By dividing the route into five movies, the developers circumvented Flash’s limitations, allowing for a seamless yet modular experience. This also enabled quick restarts after failures, as only the current segment needed reloading. The minimalist UI further enhances focus, with no clutter—just essential metrics. This design choice reflects a purist ethos, where every element serves the simulation’s realism.

Flaws are inherent to its scope. Replayability is severely limited; once the route is mastered, there is no variation—no dynamic weather, random events, or alternative trains. Sources like bitlifemod.org mention “dynamic weather and time” and “passenger management,” but these are absent from MobyGames’ authoritative description and likely conflated with later titles or speculative additions. Sticking to verified sources, the game offers a static environment. Additionally, technical datedness plagues it; Flash’s obsolescence means the game requires emulation or archival efforts to run today, and its graphics/sound are rudimentary by modern standards. Yet, these “flaws” are also features: the simplicity ensures accessibility and reduces cognitive load, making it a pure skill-based challenge.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world is the Keiō Inokashira Line, rendered through a first-person cab view. While MobyGames provides no details on graphics or sound, inference from its 2005 Flash context suggests a functional aesthetic: likely low-poly 3D or 2D sprites for tracks, stations, and surroundings, with basic textures prioritizing recognition over realism. The first-person perspective is crucial—it immerses the player directly in the driver’s seat, eliminating any abstraction. Stations like Eifukuchō and Kugayama are probably depicted with minimalist signage and platform markers, enough to orient but not distract.

Atmosphere emerges from this restraint. The lack of bustling crowds or elaborate scenery (as implied by the description) focuses attention on the tracks and signals, creating a meditative, almost hypnotic experience. The rhythmic sound of wheels on rails, perhaps accompanied by simple station chimes or engine noises (though unconfirmed), would complete the sensory palette. In Flash games of this era, sound was often sparse but effective—used sparingly to denote key events like braking or arrival.

These elements contribute to a world that feels authentically operational. The art and sound don’t aim for spectacle but for credibility, reinforcing the game’s thesis that train driving is about feel and timing, not flashy visuals. The setting becomes a character in itself: a familiar yet alien urban transit corridor, inviting players to see the everyday with new appreciation.

Reception & Legacy

Critical reception was negligible; Inokashira Line Simulator 2 garnered only one user rating on MobyGames (4.6/5) with zero critic reviews, indicating it flew under the radar of mainstream gaming press. Its commercial impact was minimal, as freeware distribution through browsers meant no sales data, but its accessibility likely cultivated a tiny, dedicated player base. On MobyGames, only three collectors have added it to their profiles, underscoring its obscurity.

However, its legacy persists in niche circles. As part of RealRailway’s series—including Keio Line Simulator 2 (2001) and later titles like Ikebukuro Line Simulator (2010) and Enoshima Line Simulator (2010)—it represents an early effort to document specific Japanese rail lines digitally. This series, while obscure, prefigured modern “transit simulators” and detailed route-based games like Train Simulator (Dovetail Games), albeit with far less polish. Its preservation on archival sites like FlashArch ensures it survives the demise of Flash, cementing its status as a historical artifact for retro gaming and simulation enthusiasts.

Influence is indirect but notable. By focusing on a single real-world route, Inokashira Line Simulator 2 championed authenticity over scale—a philosophy that resonates in contemporary indie simulators like Euro Truck Simulator 2 or Farming Simulator, which prioritize localized realism. It also demonstrates the potential of web-based platforms for specialized simulations, a concept later expanded by browser-based training tools and educational games.

Compared to contemporaries like Microsoft Train Simulator (2001), which offered expansive routes and complex controls, Inokashira Line Simulator 2 is a Study in contrasts: where the latter aimed for breadth, the former sought depth in microcosm. This makes it a curio for historians—a glimpse into an alternative path for simulation design that valued discipline over diversity.

Conclusion

Inokashira Line Simulator 2 is a paradox: a game so minimal it borders on interactive artifact, yet so focused it achieves a form of transcendental realism. Its strengths—uncompromising authenticity, elegant simplicity, and historical significance as a Flash-era simulation—are also its weaknesses, given its limited scope and technical obsolescence. For the average gamer, it offers little beyond a novel, brief distraction; for the historian or enthusiast, it is a vital piece of the simulation genre’s puzzle, illustrating how niche projects can capture the soul of an experience without compromise.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, it occupies a quiet but firm place: a testament to the idea that games need not be complex to be meaningful, and that the act of simulation itself can be a profound form of play. As both a product of its time and a timeless exercise in minimalism, Inokashira Line Simulator 2 deserves recognition not as a classic, but as a cult artifact—a distilled essence of rail operation that continues to resonate with those who seek the extraordinary in the ordinary. Its legacy is a reminder that in the vast cosmos of gaming, there is beauty in the single, well-executed routine.