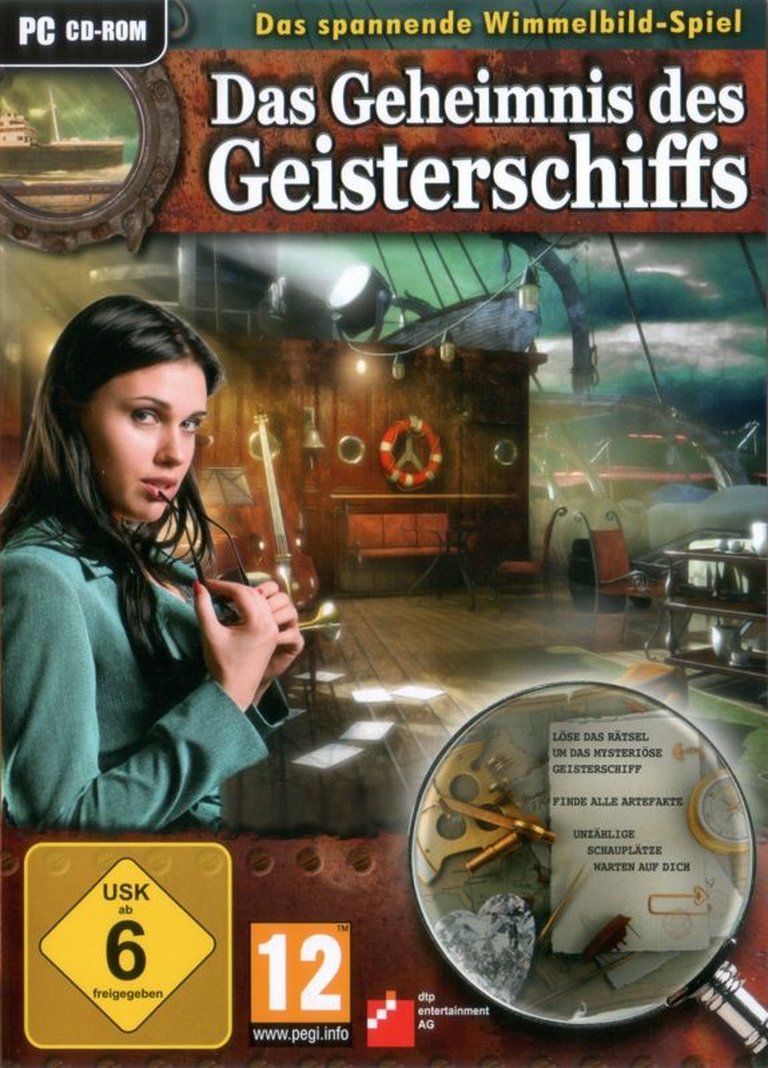

- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: dtp entertainment AG

- Developer: House of Tales Entertainment GmbH

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

Description

In ‘Curse of the Ghost Ship’, a woman’s sailing trip turns disastrous when her vessel is hit by the ancient, abandoned ship Pride. She wakes up onboard the ghost-infested vessel and, while trying to escape, discovers a mysterious ghost with a pivotal role, immersing her in a detective-style mystery set against the eerie backdrop of the haunted ship, combined with first-person hidden object gameplay and puzzle-solving.

Gameplay Videos

Curse of the Ghost Ship Cracks & Fixes

Curse of the Ghost Ship Patches & Updates

Curse of the Ghost Ship Guides & Walkthroughs

Curse of the Ghost Ship: A Spectral Echo in the Casual Adventure Pantheon

Introduction: A Ghost in the Machine of Casual Gaming

In the vast, overcrowded cemetery of casual adventure games from the late 2000s and early 2010s, few titles sink into obscurity as completely as Curse of the Ghost Ship (German: Das Geheimnis des Geisterschiffs). Released in June 2010 by German studio House of Tales Entertainment and publisher dtp entertainment AG, this first-person hidden object adventure represents a fascinating, if ultimately minor, confluence of narrative ambition and genre convention. It arrived at the zenith of the hidden object boom, a period saturated with titles that often prioritized repetitive mechanics over memorable storytelling. Curse of the Ghost Ship Attempted to buck this trend by weaving a more integrated mystery around its core hidden-object gameplay, suggesting a studio not content to merely follow trends but to subtly evolve them. My thesis is this: while the game is a product of its time—visually dated, mechanically familiar—its deliberate design choices, particularly its unconventional hidden-object paradigm and its commitment to a cohesive supernatural narrative, mark it as a thoughtful, if flawed, artifact that sheds light on a specific, commercially crucial moment in adventure game history. It is not a lost masterpiece, but it is a compelling case study in how narrative and mechanics can be fused within the rigid constraints of a mass-market genre.

Development History & Context: The House of Tales in a Crowded Market

To understand Curse of the Ghost Ship, one must first understand its developer, House of Tales Entertainment GmbH. Founded in 2002 in Bremen, Germany, the studio carved a niche for itself in the narrative adventure space with titles like The Mystery of the Druids (2008) and later Venetica (2009) and 15 Days (2009). Their pedigree was in more “hardcore” point-and-click adventures, often with historical or fantastical settings. Curse of the Ghost Ship thus represents a deliberate pivot. The year 2010 was peak “casual” for PC gaming. The hidden object genre, popularized by Big Fish Games and others, was a multi-million dollar enterprise. Studios, including established ones like House of Tales, often created “fast-follow” titles for this lucrative market.

The technological constraints were telling. The game’s system requirements (Windows XP/Vista, 1.2-2.5 GHz CPU, 512MB RAM, DirectX 9) place it firmly in the pre-high-definition casual era. The visuals are pre-rendered 2.5D stills with limited animations—a standard, cost-effective approach for the genre. The credits, listing 40 individuals, show a focused team. Key figures like Game Designer Stephan Naujoks (also credited for story/dialogues) and Art Director Sebastian Wessel were instrumental. Notably, the music and sound were outsourced to the respected German studio Dynamedion (Tilman Sillescu, Axel Rohrbach, Carsten Rojahn), indicating a desire for a professional auditory experience despite a likely modest budget. The publisher, dtp entertainment AG, was a major German player in the adventure space, known for localizing and publishing titles like The Longest Journey and Syberia. This collaboration suggests House of Tales was leveraging dtp’s distribution channels to reach the casual German and European markets, where the game’s German title and origin would have held more sway.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Pride’s Eternal Loop

The plot, as distilled from descriptions and walkthroughs, is a classic supernatural mystery with a high-concept twist: the “Pride of the Atlantic,” a luxury ship that sank 80 years prior with the priceless “Florentine” diamond of Austrian emperors, reappears on each anniversary of its sinking to relive its final hours. The protagonist, treasure hunter Annie O’Connors, is tasked with recovering the diamond to break the curse. The narrative structure is revealed through the walkthrough’s chapter headings (“Ten p.m.”, “Eleven p.m.”, etc.), confirming the game’s central mechanic: the player is racing against the clock through the ship’s doomed timeline.

Thematically, the game explores curse as cyclical inescapability and redemption through restitution. The ship’s fate is not just to be haunted, but to be trapped in a temporal loop, re-enacting its tragedy. Annie’s role is less that of a classic adventurer and more of an exorcist of time; her success is measured not by finding treasure, but by returning the stolen diamond to the mortal world—a symbolic act of righting a historical wrong. The ghost encountered is not a simple antagonist; the walkthrough shows interactions where the ghost is dragged to locations by the player to solve puzzles (“Drag the GHOST to the valve,” “Drag the GHOST to the helmet”). This Mechanic implies the ghost is a tool or a key to understanding the ship’s history, blurring the line between hinderer and helper. The ghost’s ultimate betrayal in the final Reversi puzzle (“the ghost will try to get you”) adds a layer of distrust, suggesting the spirit’s motives are complex and potentially malignant. The narrative, while sparse in dialogue by adventure standards, is conceptually richer than the average “find hidden objects to progress” fare, aiming for a cohesive, atmospheric mystery.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Paradigm Shift in Searching

Here lies Curse of the Ghost Ship’s most significant and historically interesting design choice. The source material explicitly states: “the gameplay differs from most other examples of the genre in that the player is not given a complete list of all the things he must find, knowing only the type of objects to look for, e.g. ‘find nine objects that can be opened or open something.'” This is a profound deviation from the standard hidden-object formula, where a list of 10-20 specific items (e.g., “candle,” “key,” “crown”) is provided. Instead, players are given a category and a quantity.

Analysis of this System:

* Cognitive Load & Discovery: This mechanic transforms the gameplay from a simple visual search into a more abstract puzzle. The player must interpret the category (“objects that can be opened” likely includes doors, chests, books, bottles) and scan the scene for potential interactables. It rewards lateral thinking and environmental reading over pure object recognition.

* Pacing and Tension: Without a concrete list, the player can’t efficiently tally progress. The satisfaction comes from a moment of realization—”Ah, that is an openable object!”—rather than checking off a list. This injects a subtle puzzle element directly into the hidden-object scene.

* Integration with World: The category often relates to the scene’s function (e.g., in a kitchen, “find nine utensils” or “find nine things that hold liquid”). This reinforces the setting and narrative purpose of the location, making the hidden-object act feel less arbitrary and more diegetic.

* The Help Point System: The “help points” that accumulate over time and can be used to reveal a single object or skip a mini-game is a balanced concessions to player frustration. It acknowledges the increased difficulty of the category-based search while preserving the core challenge for those who resist hints.

The walkthrough reveals a standard adventure backbone: inventory item collection, combination (“Combine the STICK and HAMMER HEAD”), and use in the environment. The mini-games are genre staples: a tile-matching puzzle with a sequence, a chess “8 queens” puzzle, a memory card game, a “find the differences” paired image puzzle, a Hanoi Tower variant, a circuit-pathing puzzle, and a Reversi (Othello) match against the ghost. Their integration is functional, often serving as gates to new areas or crucial inventory items. The critique must be that while the hidden-object mechanic is innovative, the adventure puzzles themselves are pure filler—standard logic challenges with no narrative integration beyond “this door is locked by a puzzle.” The two systems (category-hidden-objects and isolated logic puzzles) exist in parallel rather than symbiotically.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Competent Ambiance, Limited Scale

The game’s setting—the spectral, eternally sinking Pride of the Atlantic—demands a specific atmosphere. The pre-rendered 2.5D visuals, while technically basic by 2010 standards (even for casual games), accomplish this through art direction. The screenshots show detailed, moody interiors: a cluttered deck, a grand but decayed dining room, a boiler room with pipes. The color palette is desaturated, leaning on blues, grays, and browns to evoke dampness, age, and melancholy. The first-person perspective is effective for immersion, though the static backgrounds limit grand vistas.

The sound design, credited to Dynamedion, is where the atmosphere likely receives its greatest boost. A professional soundtrack and sound effects were clearly a priority. One can infer creaking wood, distant thunder, the slap of waves, and a haunting, minimalist score from the team’s portfolio. This auditory layer is essential in compensating for the lack of animation and the graphical simplicity, selling the “ghost ship” conceit. The UI is standard for the genre: a notes icon for journal/progress, a hint/compass button, and an inventory bar. It is functional and unobtrusive.

The world-building, however, is environmental rather than lore-heavy. The walkthrough mentions finding a “Passenger List” and encountering the ghost repeatedly, but there’s no sense of a deep, explorable history beyond the central curse premise. The ship feels like a series of puzzle-connected rooms rather than a cohesive, lived-in space with its own stories. This is a common genre limitation, but it’s notable given the narrative aspirations.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Dampening of a Modest Experiment

Curse of the Ghost Ship exists in a state of near-total critical and commercial obscurity. The provided MobyGames data is telling: “Moby Score: n/a”, “Collected By: 5 players”, and crucially, “Be the first to add a critic review!” and “Be the first to review this game!” for player reviews. This is the epitome of a forgotten title. Its listing on sites like My Abandonware and its availability as a free download (with a German NoCD patch) confirm its commercial failure and transition to abandonware.

Why did it vanish?

1. Market Saturation: 2010 was the beginning of the end for the pure hidden object boom. The market was glutted, and differentiation was nearly impossible without a massive brand license.

2. Lack of Marketing: From the data, dtp’s marketing efforts (headed by Thorsten Hamdorf) seem to have been minimal, likely focused on their bigger German releases. No English-language reviews appear in the provided sources from major outlets.

3. Niche Mechanic: The category-based hidden object search, while clever, may have been too different. Players of the genre have deep-seated expectations. A list is a comforting contract. Changing that fundamental interaction risked alienating the core audience without attracting a new one.

4. Studio Trajectory: House of Tales was moving toward more traditional, 3D adventures and eventually seems to have ceased original development. Curse of the Ghost Ship stands as a solitary, genre-detour footnote in their catalog, sandwiched between Venetica and their final game, The Dagger of Amon Ra (a re-release). Their legacy is not tied to hidden objects.

Its influence is therefore negligible to non-existent. It did not spawn a series. It is not cited as an inspiration in developer interviews or design post-mortems. Its innovative hidden-object mechanic was not adopted by the genre, which largely continued with the list-based system until the market itself collapsed. It represents a “what if” road not taken: a path where hidden object games could have evolved more deeply integrated puzzle systems earlier. Instead, the genre’s later evolution came from hybridizing with other casual genres (match-3, time management) rather than deepening its core search mechanic.

Conclusion: A Cursed Fate of Its Own Making

Curse of the Ghost Ship is a paradox. It is a game haunted by the ghost of its own unrealized potential. From a historical perspective, it is an invaluable document of a studio experimenting within a commercial straitjacket. Its category-based hidden-object system is a genuinely smart design pivot that, with more refinement and a stronger adventure backbone, could have subverted genre expectations. Its narrative, while simple, demonstrates a clear intent to create a cohesive, atmospheric mystery where player action has temporal stakes.

However, as a game, it is ultimately average. The adventure puzzles are generic and disconnected. The visual presentation, though moody, is static and low-resolution even for 2010. The lack of any discernible reception suggests it failed to find an audience, likely because its innovations were either too subtle for casual players to notice or too frustrating for them to embrace. It lacks the polish, charm, and marketing push of genre leaders like Mystery Case Files or Haunted House.

Its place in video game history is not one of influence or acclaim, but of representative specimen. It exemplifies a moment of transition—the point where narrative adventure studios like House of Tales dipped into the casual boom, sometimes producing works that were conceptually interesting but commercially stillborn. It is a ghost in the machine of gaming history: visible in the archives, with a clear form and story, but having passed through the world with so little impact that it barely registered a ripple. For the historian, it is a must-study case study in genre design and market forces. For the player, it is a perfectly functional, 3-4 hour diversion, now free to experience, that offers a clever twist on a tired formula—a twist that, in the end, was not enough to save it from the very curse it themed: an eternity of repetition and obscurity.