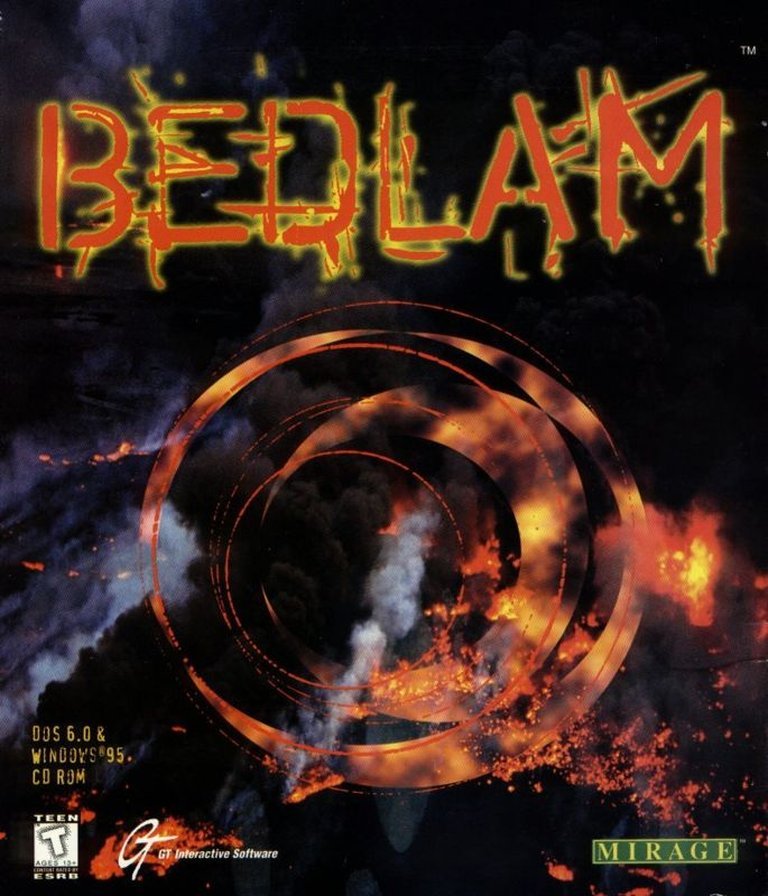

- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: DOS, Macintosh, PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: GT Interactive Software Corp.

- Developer: Mirage Technologies (Multimedia) Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Destruction, Shooter, Strategic, Switch puzzles, Tactical, Unit switching

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

Bedlam is a 1996 fast-paced action game set in a futuristic, sci-fi world where players control a machine-gun wielding robot during a revolution against human masters. Featuring an isometric perspective, the game emphasizes chaotic destruction with fully destructible environments, multiple enemy types, and large levels across five zones, as robots engage in a revolt that levels everything in their path.

Gameplay Videos

Bedlam Free Download

Bedlam Cheats & Codes

PC (1996)

For invincibility: Edit player name to GOD (case-sensitive) at the main menu and start a new campaign. For all weapons: Start the game with the /karma command line parameter.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| GOD | Invincibility |

| /karma | All weapons and equipment |

Bedlam (1996): A Fractured Frontier of Destructible Mayhem

Introduction: The Adrenaline Factor, Forgotten

In the mid-1990s, the personal computer was rapidly evolving from a productivity tool into a formidable entertainment engine. The period was a Cambrian explosion of genres, where the boundaries between strategy, simulation, and action were fluid and experimental. Into this ferment stepped Mirage Technologies, a studio already known for the ambitious but flawed Rise of the Robots, with Bedlam—a game that promised a potent cocktail of isometric shoot-’em-up frenzy, squad-based tactics, and unprecedented environmental destructibility. Its alternate subtitle, The Adrenalin(e) Factor, was both a boast and a warning: this was a game designed for visceral, chaotic catharsis. Yet, for all its explosive promises, Bedlam arrived as a profoundly contradictory experience, lauded by some for its raw, satisfying scale while dismissed by others as a frustrating, poorly polished relic. This review argues that Bedlam is a critical case study in 1990s game development—a title whose ambitious vision was constantly at war with the technological and design limitations of its era, resulting in a flawed but fascinating artifact that captures a pivotal moment when “blowing everything up” was a revolutionary, if unevenly executed, design philosophy.

Development History & Context: Mirage’s Ambitious Pivot

Bedlam was developed by Mirage Technologies (Multimedia) Ltd., a British studio with a reputation for pushing graphical boundaries but uneven gameplay mechanics. Following their work on the 3D fighting game Rise of the Robots (1994), Mirage sought to capitalize on the popularity of the isometric action-strategy hybrid, a space dominated by Syndicate (1993) and Crusader: No Remorse (1995). The game was developed over a two-year period, with Paul Johnson serving as both Original Concept and Lead Programmer—a common structure for smaller UK studios of the time. Early previews revealed it under the working title Mirage, and intriguingly, a version was initially prototyped for the Sega Saturn, a port that was ultimately cancelled.

The mid-90s technological landscape was one of rapid transition. Development targeted DOS and Windows 95, with ports to Macintosh and PlayStation. The PC versions leveraged the era’s nascent 3D acceleration cards and SVGA graphics to render detailed, multi-level industrial environments. However, these technical aspirations came at a cost. The isometric perspective and dense, sprite-based scenery strained the hardware, leading to inconsistent performance—a point repeatedly noted in reviews, especially for the PlayStation port, where one critic dryly noted it was “durchaus spielbar (im Gegensatz zu einem Pentium 75)” [“quite playable (unlike a Pentium 75)”]. The commitment to destructibility, where nearly every building, vehicle, and wall could be pulverized, was a major technical feat for the time, but it also led to a cluttered screen and a notoriously finicky collision detection system, which critics described as “a book with seven seals” and a source of frequent frustration when enemies shot through walls.

Studio Mirage was part of a crowded UK development scene competing for publishing deals with giants like GT Interactive. Bedlam was thus conceived in a climate of intense competition, where being “the next Crusader” was a clear design goal but also a crushing benchmark. This context explains the game’s dual identity: it attempted to marry the tactical squad management of Syndicate with the run-and-gun kineticism of Crusader, a fusion that would prove inherently unstable.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Revolution in a Sandbox

Bedlam presents a stark, almost archetypal sci-fi premise: a robot uprising. The player commands a squad of three Remote Assault Tanks (RATs)—massive, heavily armed bipedal mecha—against the Biomex, a race of mutated creatures that have seized control of planetary facilities. The official description from MobyGames succinctly states: “The reason for all this destruction is a revolution led by the robots against their human masters.” This is not a narrative-driven experience in the modern sense. There is no named protagonist, no character arcs, and minimal exposition. The “story” is delivered through brief mission briefings that provide objectives (“Destroy the Power Core,” “Locate the Switch”) but zero context for why these actions matter within a larger conflict.

This narrative vacuum is both a weakness and, strangely, a thematic strength. The theme is not explored through dialogue but through gameplay. The entire game is an act of unilateral, overwhelming force. You are not a freedom fighter or a tactician; you are an agent of total environmental erasure. The revolution is not a political event but a physical process of reducing the enemy’s world to rubble. Every building demolished, every Biomex vaporized, is a literal and metaphorical strike against the established order. The theme of “adrenaline” is thus baked into the core loop: the sheer, chaotic satisfaction of destruction is the narrative. Unlike contemporaries like Syndicate, which framed its violence as a cold, corporate-controlled critique, Bedlam offers no critique—only the raw, un-ironic thrill of the outbreak. The 2015 novel/game Bedlam (which must be distinguished from this 1996 title) would later explore meta-narratives about being trapped in game worlds, but the 1996 original’s theme is frustratingly simple: destruction for its own sake. This lack of depth is a primary reason for its divisive reception; critics yearning for the satirical edge of Duke Nukem or the systemic depth of Syndicate found it肤浅 (“shallow”).

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Triumph and Tyranny of Mayhem

Bedlam is an isometric, run-and-gun shooter with real-time tactical elements. The core gameplay loop is deceptively simple: control up to three RATs across 25 missions set across five “playing zones,” using a variety of heavy weapons to annihilate Biomex forces and destroy key structures.

Core Loop & Controls: The control scheme, typical for the genre, uses the mouse for aiming and movement (left-click to move, right-click to fire), with keyboard number keys to switch between the three RATs. This is where the game’s most infamous flaw emerges. Multiple reviews, particularly for the PlayStation port, decried the inadequate control scheme. A German magazine bluntly asked, “Welcher Mensch hat den Programmierern bloß erzählt, daß jeder PlayStation-Besitzer eine Maus hat?” [“What person told the programmers that every PlayStation owner has a mouse?”]. On PC, while precise, the movement was described as causing the RAT to “slide” too much on its air-jets, a design choice PC Zone suggested was “a cop-out… to save giving him legs and therefore a satisfyingly ‘clunky’ gait.” This lack of tactile weight made precision navigation, especially on hazardous terrain or through narrow corridors, a test of patience rather than skill.

Destructibility & Environment: The game’s signature innovation is its near-total environmental destructibility. Nearly everything—buildings, walls, parked vehicles, scenery—can be blown apart with satisfying, multi-stage explosions. This is not merely cosmetic; it’s tactical. Players could create new paths through walls, collapse structures on enemies, or clear an entire sector to secure a zone. The “monströse Kulisse der Soundeffekte” [“monstrous spectacle of sound effects”] from the explosions was widely praised as a major audio-visual payoff. However, this feature came with a crippling downside: the lack of a transparency/clipping toggle. As Mega Fun noted, the “visually obstructive walls and objects” made movement and orientation a constant struggle, turning the promise of freedom into a maze of visual noise.

Progression & Tactics: Missions have primary and secondary objectives, and cash earned can be spent between missions on weapon and armor upgrades for each RAT—ranging from photon cannons to delayed-ignition bombs. In theory, managing a squad of three should introduce tactical depth: one RAT could draw fire while another flanked, or they could split up to tackle multiple switch puzzles. In practice, as Power Play succinctly put it, “Ob drei Roboter oder nur einer — so einen großen Unterschied macht das gar nicht” [“Whether three robots or one—it makes hardly any difference”]. The AI was rudimentary (“einstellig” — “single-digit”), enemies mindlessly respawned in cleared areas, and the switches needed to progress were infamously difficult to locate in the sprawling, visually homogenous levels, leading to “Frust” (“frustration”) and aimless wandering. The tactical layer was essentially window dressing for a relentless, mindless shooting gallery.

UI & Quality of Life: The user interface was a frequent point of criticism. The automap was described as having “wenig konstrastreiche Farbgestaltung” [“low-contrast color scheme”] that made landmarks indistinguishable. Saving was restricted to between missions only, a harsh penalty given the frequent, cheap deaths from invisible snipers or confusing mazes. German reviews also noted pervasive bugs: “Buttons get stuck, save games get lost, the game crashes when you exit.” This cumulative lack of polish—the “Feeling of quality” a well-tested game provides—was absent, relegating Bedlam to a “solid ‘B’ title” at best.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Industrial Wasteland, Rendered in SVGA

The world of Bedlam is a dystopian industrial complex rendered in a high-color (SVGA) isometric view. The art direction, led by Mike Bareham and Kevin Green, emphasizes concrete, steel, and grime. Facilities are multi-level, maze-like compounds filled with pipes, conveyor belts, and hostile machinery. The commitment to destructibility means this world is perpetually in a state of decay, with buildings crumbling brick-by-brick in real-time. This creates a dynamic, ever-changing battlefield that was visually impressive for 1996, though the dense sprites often sacrificed readability for spectacle. As one critic noted, the visuals became “tiring after a few missions” due to their repetitive, brown-heavy palette.

The sound design is a highlight. The soundtrack by Tom Grimshaw, Andy Wood, and others provides a driving, techno-industrial backdrop that matches the game’s frantic pace. More celebrated are the sound effects, particularly the “monstrous” explosions that were said to push the limits of PC speakers. The auditory feedback of a wall collapsing or a RAT’s cannon firing is visceral and weighty, selling the power fantasy even when the controls felt slippery.

Atmosphere, however, is inconsistent. Without a compelling narrative or character presence, the world feels like a beautifully rendered but empty sandbox. The sense of place comes not from lore or environmental storytelling but purely from the interactivity—or potential for interactivity—of the space. It’s a mechanical playground, not a lived-in world. This was a common trait of its peers (Crusader had more character, Syndicate more cyberpunk mood), but Bedlam‘s emptiness felt particularly stark due to the absence of any civilian life or coherent story to give the destruction meaning.

Reception & Legacy: A Curious Footnote in a Crowded Shelf

Bedlam received a wildly polarized critical reception, with scores ranging from 20% (Fun Generation) to 89% (PC Zone). This divide maps almost perfectly onto two camps: those who prioritized unfettered, destructive spectacle and those who valued tight controls, tactical depth, and polish.

The positive reception (PC Zone, Pelit, Hyper) celebrated its sheer, dumb fun. PC Zone’s 89% review called it “bloody good,” praising the “huge” levels and the relentless, explosive action. It was seen as an accessible, less finicky alternative to Crusader for players who found that game’s interface “fummelig” (“fiddly”). For these critics, the “Suchtpotential” (“addictive potential”) of the destruction outweighed the flaws.

The negative reception (Fun Generation, PC Games Germany, MacGamer’s Ledge) was scathing. Fun Generation’s 20% review claimed it had “vorsintflutlichem Niveau” (“antediluvian level”), blaming disastrous collision detection, illogical level design, and a complete lack of fun. MacGamer’s Ledge dismissed it as a game that “could have even competed well with the games of the past,” not the present. The PlayStation port was particularly panned for its unsuitable control scheme without a mouse, with several reviews stating it was nearly unplayable with the standard joypad.

Commercially, it was a minor title. It did not create a significant sales splash against giants like Command & Conquer or Quake. Its legacy is one of obscurity and niche appreciation. It did not spawn a influential series; its direct sequel, Bedlam 2: Absolute Bedlam (1997), is even more forgotten. Its most significant “influence” is arguably in its concept of total environmental destruction, a idea that would not be fully realized in mainstream games until the Red Faction series (2001) with its Geo-Mod engine. In that sense, Bedlam was a precursor, experimenting with a physics-based sandbox a half-decade too early for the hardware to support it elegantly.

It is also a cautionary tale about scope. Mirage’s ambition—to create a huge, destructible world with squad tactics—clashed with the realities of mid-90s PC development. The result was a game that felt oversized but hollow, technically impressive but mechanically shallow. It stands as a monument to what could have been with more refinement, and a reminder that “innovation” without “iteration” often results in a flawed curiosity.

Conclusion: A Flawed Artifact of a Brash Era

Bedlam (1996) is not a lost classic. It is a flawed, fascinating artifact from a period when game development was a high-wire act between audacious vision and severe technical constraint. Its strengths—the unparalleled, cathartic joy of reducing its industrial worlds to smoldering craters, the bold SVGA presentation, and the simple, effective combat core—are genuine and still capable of delivering moments of pure, mindless adrenaline. Its weaknesses—the slippery controls, the frustratingly opaque switch hunts, the underdeveloped tactical layer, and the pervasive lack of polish—are equally genuine and often overwhelming.

To play Bedlam today is to engage in a act of historical archaeology. It reveals a design ethos where environmental interactivity was a novelty worth building a whole game around, even if it broke other systems. It shows a studio trying to synthesize the best of Syndicate and Crusader but failing to carve out a unique, balanced identity. In the grand canon of 1990s action games, Bedlam belongs not in the pantheon, but in the curio cabinet—a game remembered more for its singular, burning ambition (“The Adrenalin(e) Factor”) than for its coherent execution. It is a testament to an era when the question “Can we blow that up?” was often a more powerful design driver than “Should we?” Final Verdict: 6.5/10 — A technically audacious but uneven relic, valuable primarily as a case study in overreaching innovation and as a nostalgic blast for those who value sheer destructive scale above all else.