- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH

- Developer: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Tile matching puzzle

- Setting: Ancient, Classical, Japan, Medieval

Description

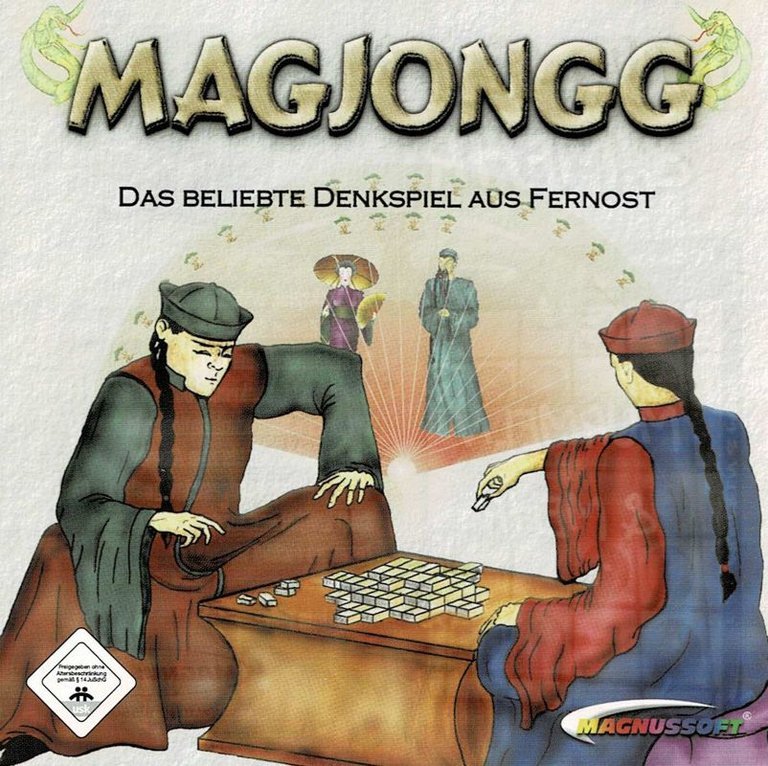

Magjongg is a single-player digital adaptation of the classic Mahjong solitaire tile-matching puzzle, set within a Japanese historical aesthetic. Players engage in the strategic removal of paired tiles from intricate, layered layouts, with the game offering a variety of visual themes, different board configurations, and adjustable difficulty levels to challenge their skills.

Magjongg: A Silent Artifact in the Digital Diaspora of an Ancient Game

Introduction

In the sprawling canon of video game history, certain titles exist not as landmarks but as subtle waypoints—games that arrived quietly, left little trace, and yet occupy a necessary space within a genre’s evolution. Magjongg (2005), developed and published by the German studio magnussoft Deutschland GmbH, is one such artifact. It is a solitary, no-frills digital adaptation of the tile-matching puzzle commonly known in the West as “Shanghai” or “Mahjongg solitaire.” At first glance, it appears merely as another entry in a crowded field of casual PC puzzlers from the mid-2000s. However, to dismiss it is to overlook its role as a commercial footnote in the much larger, centuries-spanning narrative of Mahjong’s journey from Chinese parlor to global pixel. This review argues that Magjongg’s significance lies not in its innovation, but in its embodiment of a specific moment: the commodification of a cultural pastime into a commodified, downloadable software product for the Western casual market. It represents the tail end of an era where such adaptations were local, studio-specific projects before the genre’s consolidation under mega-franchises and mobile apps.

Development History & Context

The Studio & Vision: Magnussoft Deutschland GmbH was a mid-tier German publisher active in the 2000s, known for budget-friendly casual and simulation titles for the PC market, often distributed through retail channels in Europe. Unlike a studio with a pronounced creative signature, Magnussoft operated pragmatically, identifying popular casual genres (puzzles, card games, simple simulations) and producing competent, low-cost implementations to serve a demand from non-English-speaking European markets. Magjongg fits this model perfectly: a straightforward interpretation of a well-known puzzle format, localized for a German-speaking audience (evidenced by the USK 0 rating and German publisher), with no apparent ambition beyond functional execution.

Technological & Market Constraints: The game was developed for Windows in 2005, placing it in the late era of pre-steam, retail-and-download-shareware casual gaming. Technologically, it required no advanced 3D acceleration; it is a 2D, top-down tile-matching game using point-and-click input, placing minimal demands on system resources. This allowed it to run on the vast install base of Windows XP machines, a key factor for its target demographic of older, casual players. The “four different graphics sets, different game fields and difficulty levels” mentioned in its brief description reflect the era’s common practice of providing visual and mechanical variance to extend replayability without significant development cost.

Gaming Landscape: 2005 was a pivotal year for casual PC gaming. The “Big Fish Games” model of curated, downloadable casual titles was thriving. Microsoft’s Mahjong Titans had been a staple of Windows Vista (released 2007, but in development). The success of PopCap’s Bejeweled and Peggle had proven the market’s appetite for polished, accessible puzzlers. Magjongg entered this landscape without a flagship brand or a novel hook. It was not a narrative-driven experience like the contemporaneous Mah Jong Quest series (2005-2008), nor a feature-rich compilation like Mah Jongg Dimensions. Instead, it was pure mechanics—a clean, if unremarkable, implementation of the Shanghai formula, aimed at the segment of players seeking a familiar, no-distraction tile-matching session.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Magjongg makes no pretense of narrative. Where sources detail the rich cultural tapestry of Mahjong—its ties to Chinese cosmology, its social function as a “social glue,” its evolution from gambling parlor to family table—Magjongg strips all context away. It presents the tiles as abstract patterns: circles, bamboo, characters, dragons, and winds, devoid of their symbolic meaning. There is no story, no characters, no dialogue. The setting is listed merely as “Japan (Ancient/Classical/Medieval)” on MobyGames, a puzzling and historically inaccurate categorization that conflates the game’s Chinese origins with a generic “Orientalist” aesthetic common in Western digital adaptations of the era.

This narrative vacuum is, in itself, a thematic statement reflective of its time and place of development. The game treats Mahjong not as a living cultural practice but as a pure puzzle mechanic. The spiritual, social, and historical weight of the tiles is entirely excised. The player is not a participant in a millennia-old ritual of social bonding or strategic gambit; they are a solitary problem-solver arranging geometric shapes on a screen. This represents a specific Western, late-capitalist interpretation of Mahjong: its transformation from a game-for-people into a product-for-consumers. The thematic depth exists not in the game itself, but in the gap between its form and its source material—a gap populated by centuries of myth, misunderstanding, and cultural translation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The core of Magjongg is the classic Shanghai/Mahjongg solitaire algorithm:

1. Setup: A complex, layered layout (pyramid, turtle, etc.) of face-up tiles is generated. Each tile appears in a set of four identical copies.

2. Rule: Only tiles that are “free”—meaning no tile is placed directly on top of them and at least one long edge is unobstructed—can be selected and paired.

3. Goal: Clear the board by matching all pairs.

4. Loss Condition: The board reaches a state where no legal pairs remain, and free tiles are still present.

Systems & Execution:

* Core Loop: The loop is simple, addictive, and contemplative: scan the board, identify a match, click-pair, watch tiles vanish, reassess the newly exposed tiles. This is the entire gameplay cycle.

* Progression & Variation: The “different game fields” provide the primary variation. Players select from various predefined layouts (likely including the classic “dragon” and “turtle” formations). The “difficulty levels” primarily alter the density and height of the tile stacks, increasing the cognitive load of visualizing blocking tiles. There is no character progression or unlockable content narrative-wise; progression is purely the player’s own skill in pattern recognition and spatial planning.

* UI & Input: The interface is pure point-and-click. Hovering over a selectable tile likely highlights it, and a second click selects its match. A “shuffle” or “undo” function is almost certainly present, as is standard in the genre, as a lifeline for difficult boards. The UI is functional, utilitarian, and dated by modern standards—a window within a window, with basic buttons, reflecting its shareware/casual-box roots.

* Innovation & Flaws: Magjongg demonstrates zero innovation. It is a faithful, conservative implementation. Its potential flaws are the genre’s endemic ones: the inherent randomness of tile distribution can lead to unwinnable boards—a source of frustration mitigated only by the shuffle function. The lack of a random generator means players can eventually memorize the specific layouts, reducing replayability. Its biggest “flaw” is its sheer mediocrity; it does nothing better than dozens of contemporaries and lacks the aesthetic polish of Mah Jong Quest or the dynamic 3D layouts of later games.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Given the absence of narrative, “world-building” here refers solely to the audiovisual presentation, which aims for a serene, “Eastern” aesthetic.

- Visual Direction: The “four different graphics sets” are the game’s primary artistic feature. One set likely mimics traditional bone-and-bamboo tiles with delicate engraved symbols. Another may be a more colorful, stylized interpretation. A third could be a photographic or “wooden” set, and a fourth perhaps a minimalist or fantasy-themed variant. The backgrounds are static, serene images—likely idyllic landscapes (mountains, gardens, temples) meant to evoke calm. The art direction is conservative and safe, avoiding the anime flair of Mahjong Soul or the vibrant storybook style of Mah Jong Quest. It prioritizes clarity of tile symbols over artistic ambition, a practical choice for a puzzle game where readability is paramount.

- Sound Design: The soundscape is almost certainly minimal and functional. A gentle, looped ambient track (using synthesized ersatz-Asian melodies with flutes or string patches) plays in the background. The primary audio feedback is the crisp, satisfying click-clack of tiles being matched—a direct digital echo of the tactile sound that gives Mahjong its name (“máquè,” or “sparrows”). A gentle chime or positive tone signifies a successful match; a dull thud or error buzz indicates an invalid move. This sound design is effective if unoriginal, reinforcing the meditative, repetitive nature of the gameplay loop.

These elements combine to create an atmosphere of digital zen. The game is not trying to tell a story or immerse you in a world; it is trying to facilitate a state of focused, repetitive calm. In this, it succeeds on its own limited terms, providing a blank canvas for the player’s mental engagement with the puzzle.

Reception & Legacy

Critical & Commercial Reception: Magjongg exists in a state of near-total archival obscurity. There is no critic review on MobyGames, Metacritic, or any major outlet of the era. Its commercial performance is not recorded, but as a Magnussoft title, it likely achieved modest sales in German-speaking territories through retail “casual” bundles or discount bins. It represents the vast sea of un-reviewed, un-remembered casual PC games that saturated the market in the 2000s. Its only digital footprint is its bare-bones MobyGames entry, added in 2025 by a single contributor, and its appearance in aggregated lists of “Moraff’s Mahjongg” variants (a somewhat separate, long-running series by programmer Steve Moraff, though Magjongg is distinct).

Evolution of Reputation: The game has no reputation to evolve. It is a ghost in the machine of Mahjong’s digital history. While scholarly and enthusiast sources (like Sloperama, TheMahjong.com, and MahjongCompare) meticulously chart the game’s 150+ year history, its cultural variants, and its major video game milestones (from Nintendo’s Game & Watch to Shanghai (1986), Mahjong Titans (2006), and Mahjong Soul (2019)), Magjongg is nowhere to be found. It is not cited as influential, nor is it remembered fondly as a cult classic. It is a data point without data.

Influence on the Industry: Its influence is, by definition, negligible. It did not pioneer a mechanic, popularize a style, or reach a wide audience. Its legacy is to be a perfect example of the norm. It demonstrates how the Mahjong solitaire genre had, by 2005, become a replicable template. Any studio could produce a functional, visually distinct version with minimal effort and stake a claim in the casual puzzle space. In this, it is a precursor to the thousands of generic “Mahjong” apps that would later flood mobile storefronts—games with interchangeable tile-skins and no identity. Its legacy is one of commodified anonymity.

Conclusion

Magjongg (2005) is not a game to be celebrated for its artistry, innovation, or impact. It is, however, a significant object for the game historian precisely because of its ordinariness. It is a clean, competent, and utterly forgettable specimen of its time and genre. It captures the moment when Mahjong solitaire fully divorced itself from its cultural and social roots, becoming a pure, disembodied puzzle mechanic ripe for mass production and digital distribution.

Its value lies in its position within the genealogy of digital Mahjong. It comes after the genre’s foundational works (Colossus Mah Jong, Shanghai) and before its modern, community-driven renaissance (Tenhou, Mahjong Soul). It is the quiet, unassuming bridge between the era of disk-based shareware and the era of online, socialized, competitive platforms.

For the player, it offers exactly what it claims: “four different graphics sets, different game fields and difficulty levels.” For the historian, it offers a lesson in obscurity—a reminder that for every influential title, there are hundreds of Magjonggs: games that filled shelves, satisfied a passing need, and then faded into the silent, vast library of the ephemeral. Its final verdict is one of competent mediocrity: a perfectly functional puzzle game that achieves its modest goals and serves as a silent testament to the commercial democratization—and consequent dilution—of one of humanity’s most enduring games.

Final Score: 6/10 – As a casual puzzle game, it is serviceable but unexceptional. As a historical artifact, it is a perfectly preserved specimen of mid-2000s PC casual gaming’s anonymous middle.