- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Corremn

- Genre: Role-playing (RPG)

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Character classes, Hack-n-slash, Looting, Magical combat, Magical items, Melee Combat, Ranged combat, Roguelike, Traps, Turn-based

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

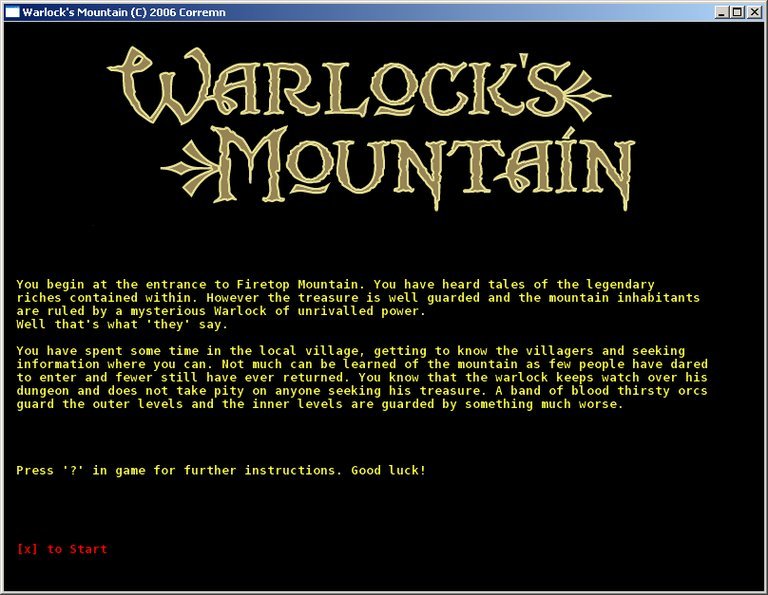

Warlock’s Mountain is a free roguelike game that reimagines the classic 1982 Fighting Fantasy gamebook ‘The Warlock of Firetop Mountain’ as a turn-based fantasy adventure. Players select from various character classes to explore a top-down mountain stronghold, engaging in hack-and-slash combat, looting treasures, avoiding traps, and ultimately confronting the evil wizard Zagor in his citadel.

Warlock’s Mountain Reviews & Reception

rpggamers.com : bringing it closest, if anything, to the book’s original computer game adaptation

Warlock’s Mountain: Review

Introduction: A Mountain of Potential, Buried Under a 7DRL Avalanche

In the vast and varied landscape of video game adaptations, few projects embody the spirit of passionate, constrained creation quite like Warlock’s Mountain. Released in 2006 as a freeware Windows title, this game is not a commercial revival or a mainstream reimagining, but a raw, unfiltered artifact from the “Seven-Day Roguelike” (7DRL) challenge—a grueling contest where developers must create a complete, playable roguelike in under one week. It represents a fascinating, if deeply flawed, first digital step in translating the 1982 Fighting Fantasy gamebook phenomenon, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, into the procedural, turn-based lexicon of the roguelike genre. My thesis is this: Warlock’s Mountain is a critical historical curio, a testament to the ingenuity of its creator and the adaptability of its source material. However, as a standalone game, it is ultimately a fascinating failure—a proof-of-concept that reveals the immense gulf between the elegant, choice-driven tension of a gamebook and the often-grindy, random demands of a traditional roguelike. Its legacy is not in its playability, but in its role as a crucial, if primitive, bridge between two distinct interactive storytelling traditions.

Development History & Context: A Week in the Life of a Dungeon

The story of Warlock’s Mountain begins not in a corporate studio, but in the isolated, caffeine-fueled sprint of the 7DRL competition. Its sole credited developer, “Corremn,” undertook the challenge in 2006, a period of significant ferment for the roguelike genre. While classics like NetHack, Angband, and Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup dominated the hardcore scene, the mid-2000s saw a surge of interest in “coffeebreak roguelikes”—shorter, more accessible titles designed for quick play sessions. Warlock’s Mountain was explicitly positioned in this space by its creator on RogueBasin, the central wiki for roguelike development.

The game was built using DemiseRL, a custom engine Corremn developed specifically for rapid roguelike construction. This technical choice is telling: it prioritized speed and robustness over graphical fidelity or complex systems. The engine’s limitations defined the game’s aesthetic—a stark choice between textmode (ASCII) graphics or a basic, optional tile-based set provided by David Gervias and Christopher Barrett. This was not a game aiming for immersion through visuals; it was a mechanical exercise. The technological constraints of 2006 for an indie, one-person project were severe: no 3D acceleration, minimal sound, and a core loop built on simple grid-based movement and turn resolution.

Crucially, Warlock’s Mountain entered a gaming landscape already saturated with Warlock of Firetop Mountain adaptations. It was not the first digital translation. A 1984 ZX Spectrum action-adventure game by Crystal Computing had already blazed that trail, and a far more ambitious 3D first-person RPG for the Nintendo DS was in development by Big Blue Bubble (released in 2009). What made Corremn’s 2006 project unique was its genre fusion: applying the deterministic, procedural, permadeath ethos of roguelikes to a gamebook famous for its static, mapped dungeon and reliance on dice rolls and player choice. It was, in the developer’s own words, an attempt to bring the book “closest, if anything, to the book’s original computer game adaptation—if a more measured and step-by-step turn-based approach.”

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: From Branching Paths to Linear Labyrinth

The foundational narrative of Warlock’s Mountain is, by necessity, the same as Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson’s 1982 gamebook. The player is an adventurer drawn to Firetop Mountain by tales of a warlock’s treasure. The goal is to descend into the volcanic caverns, survive its denizens (goblins, undead, Chaos creatures), acquire five specific keys, and ultimately confront the necromancer Zagor. The source material’s genius lies in its 400-section, non-linear structure where a single wrong turn or failed Luck test ends the adventure abruptly, incentivizing mapping, careful resource (provision) management, and repeated attempts.

The 2006 roguelike version systematically dismantles this narrative architecture. The static, meticulously crafted maze of the book is replaced by a procedurally generated dungeon of “20 main levels” and “5-10 random special levels.” The specific, numbered paragraphs that created a sense of exploring a fixed, authored space are gone. Instead, the player navigates abstract room connections, where the story is not told through branching text but through flavor text on room entry and item descriptions. The weight of a decision in the book—”If you go west, turn to 142. If you go east, turn to 89″—is replaced by the tactical weight of “Do I explore this room or heal at the stairwell?” The theme of perilous choice is not eliminated, but it is transformed from a narrative puzzle into a resource and positioning puzzle.

The characters, too, are flattened. The gamebook allows for no formal class, but the player’s starting equipment and the items found shape a de facto build. Warlock’s Mountain introduces explicit character classes (Warrior, Thief, Wizard—as per later adaptations like the 2016 Tin Man Games version, though the 2006 version’s implementation is simpler), each with “particular skills and abilities.” This shifts the theme from the book’s “any adventurer can try” to a more game-like specialization. The original’s grim, fatalistic tone—where failure is often sudden and arbitrary—is softened by roguelike conventions like checkpoints (resurrection stones) and a focus on incremental progress across runs. The core theme of confronting a monolithic evil (Zagor) remains, but the journey to him becomes a repetitive tactical exercise rather than a unique, authored quest. The narrative is no longer a story you are reading; it is a backdrop for the gameplay loop.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Clash of Gamebook and Roguelike

This is where the profound conceptual tension of Warlock’s Mountain becomes most apparent. The game attempts to reconcile two incompatible design philosophies.

Core Loop & Exploration: The game is a turn-based dungeon crawl. You move your character (represented by a glyph in textmode or a sprite in tile mode) through a grid-based dungeon. Exploration involves revealing fog-of-war, searching for traps (a core mechanic), and looting monster corpses. The procedural generation ensures no two runs are identical in layout, which directly contradicts the book’s design, where mastery came from learning a fixed map. This is the game’s greatest innovation and its greatest betrayal of the source material. In the book, learning that section 147 is a dead end filled with giant scorpions is a permanent piece of knowledge. Here, that knowledge is useless on the next run.

Combat: Combat is a simultaneous, turn-based system, as described in later adaptations and inferred from the roguelike genre’s standard. You and an enemy declare an action (attack, move, cast a spell) each turn, with outcomes resolved based on stats and positioning. This is a significant departure from the book’s simple dice-off system (highest Attack Strength wins, deals 2 damage). The 2006 version’s combat is more tactical, requiring spatial awareness and prediction of enemy movement—a nod to “Hack” rather than “Rogue,” as the MobyGames description notes. However, sources like the A-to-J Connections review (for the different 2016 version) highlight a critical flaw that likely plagued this earlier iteration: combat can devolve into circular chasing and attacking empty spaces as both sides Maneuver for position. Without complex AI or varied enemy behaviors (common in more mature roguelikes), fights risk becoming tedious wars of attrition. The lack of level progression beyond gear found in the dungeon exacerbates this; as noted in the A-to-J review, you often face stronger enemies with the same move set from the start.

Character Progression & Systems: The game replaces the iconic Fighting Fantasy trio of SKILL, STAMINA, and LUCK with “more conventional D&D character statistics.” This is a significant lore-handling decision. The book’s stats were simple and holistic; D&D’s separate Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, etc., allow for finer differentiation but add complexity ill-suited to a 7DRL’s scope. The provision-eating mechanic is retained— eating food heals wounds, a vital link to the gamebook’s survival horror. Classes provide different starting gear and abilities (e.g., a Wizard might start with mana and spells, a Thief with better trap detection), encouraging different approaches. However, without a robust skill tree or meaningful leveling (the A-to-J review notes the lack of standard RPG level-up), progression is almost entirely gear-dependent (finding a “ego weapon or armour” as per RogueBasin). This creates a high variance in run difficulty based on random loot drops, a core roguelike tenet but a potential source of frustration when key items are absent.

User Interface & Innovation: The interface is functional, designed for keyboard input. The dual graphics modes are the only real “innovation” presented as a feature. The textmode is pure retro nostalgia, appealing to the ASCII-loving roguelike veteran. The tile set provides more visual clarity at the cost of some charm. The game’s true innovative claim is its genre hybridization: it is arguably one of the first digital attempts to treat a gamebook not as a text adventure or visual novel, but as a procedural dungeon crawler. This is a fascinating design pivot that later, more polished adaptations (like Tin Man Games’) would explore more successfully with better resources.

Flaws: The flaws are endemic to its development context. The procedural generation likely lacks the hand-crafted density and puzzle integration of the original book. Secret doors, traps, and monster placements are random, not designed to create specific narrative beats or logical challenges. The lack of a persistent narrative makes the world feel generic. The absence of the book’s specific, numbered paragraphs means the evocative, paragraph-long descriptions of encounters are sacrificed for short, in-room text. The “measured, step-by-step turn-based approach” praised in the description can easily become slow and grindy, especially in later levels with numerous monsters. Saving is explicitly “a big no-no” on RogueBasin, enforcing permadeath, but with only three “resurrection stones” as checkpoints, the difficulty curve is likely brutal and sometimes unfair.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Atmosphere Through Abstraction

The world of Warlock’s Mountain is Firetop Mountain by way of NetHack. Its atmosphere is derived not from detailed 3D modeling or orchestral scores, but from player imagination fueled by sparse cues.

Visual Direction: The two visual modes serve different nostalgic impulses.

* Textmode (ASCII): This is the pure roguelike experience. ‘@’ represents the player, ‘g’ a goblin, ‘T’ a trap. Walls are ‘#’ and doors are ‘+’. It is minimalist, functional, and relies entirely on the player’s familiarity with roguelike symbols and the game’s descriptions to build a mental image of a “dank cave” or “collapsing tunnel.” Its charm is purely for the initiated.

* Tile-Based Graphics: This mode uses the tileset from David Gervias, with additions by Christopher Barrett. It is * rudimentary but functional*. Stone floors, wooden doors, and monster sprites are clear and readable, which is the primary goal of any roguelike UI. The color palette is muted (browns, greys), fitting the underground fantasy theme. It lacks the “miniatures” charm of the later 2016 Tin Man Games version, which used scanned physical miniatures for a board-game feel. Here, the art is simple pixel work, prioritizing tactical clarity over aesthetic appeal. The “paintbucket effect” mentioned in the A-to-J review for the later version is absent. The world feels like a schematic, not a place.

Sound Design: Information on sound is scarce. As a 2006 freeware 7DRL, it likely features placeholder or minimal sound effects (a beep for attacks, a crash for traps) and perhaps no music, or a single looping track. The A-to-J review of the 2016 version noted the absence of voice acting as a missed opportunity given the heavy text, a criticism that would apply even more starkly to this barebones 2006 release. The atmosphere is almost entirely text-driven.

Contributing to Experience: The stark visuals and likely sparse sound serve the gameplay-first philosophy of a 7DRL. They do not distract from the tactical grid. The “world-building” happens in the player’s mind, prompted by the brief room descriptions (“You stand before a dark chasm. A faint howling echoes from below.”) and the names of items (“Zagor’s Wand of Fire”). It captures the idea of a dungeon crawl, but not the texture of the gamebook’s specific, memorable locations like the “Stone Bridge” or “Goblin Pool.” It is a generic fantasy underworld, not Firetop Mountain as uniquely depicted by Russ Nicholson’s illustrations.

Reception & Legacy: A Niche Prototype’s Slow Burn

Warlock’s Mountain‘s reception was muted, confined to the echo chamber of the roguelike community and Fighting Fantasy fandom.

At Launch (2006): There is no evidence of mainstream or even indie press coverage. Its home on sites like RogueBasin and its availability as a free download from its author’s site (linked on MobyGames) targeted a tiny, knowledgeable audience. On MobyGames, it has been “Collected By” only 5 players as of the latest data, and has a single player rating of 3.0 out of 5. The absence of any critic reviews on MobyGames or aggregators like Metacritic underscores its obscurity. Within the 7DRL community, it would have been judged on its completion and fun factor within the one-week constraint—criteria it met to be documented. The RogueBasin entry notes it was a “Beta Project” that “stopped development (for now) due to other commitments” by 2019, indicating it was never meant to be a finished product.

Evolution of Reputation: Its reputation has grown only retrospectively and historically, not through popular reevaluation. It is now cited primarily as:

1. An Early Gamebook-to-Roguelike Adapter: It predates the more famous and polished Tin Man Games adaptations (starting with The Warlock of Firetop Mountain in 2016) by a full decade. It demonstrated that the core loop of “explore, fight, loot, survive” could map onto roguelike mechanics, even if the narrative soul was lost.

2. A 7DRL Case Study: It exemplifies the strengths and weaknesses of the format—rapid iteration, creative genre mashups, but also roughness, imbalance, and lack of polish. It is a “what if” experiment made real.

3. A Curio in the Warlock Adaptation Lineage: The Wikipedia-sourced history shows a long line of adaptations: 1984 Spectrum game, 1986 board game, 2009 DS game, 2016 Tin Man Games version. Warlock’s Mountain (2006) sits between the early, loose adaptations and the later, fidelity-obsessed ones. It represents a path not taken: the “roguelike” path, as opposed to the “board-game sim” (Tin Man) or “3D dungeon crawler” (Big Blue Bubble) paths.

Influence: Direct influence is hard to trace. It was a obscure fangame. However, it exists within a clear lineage of Fighting Fantasy fangames and demonstrates the universal appeal of the source material for digital reinterpretation. Its procedural approach is conceptually closer to the randomized “special levels” of some Angband variants than to the static maps of the official adaptations. Its greatest influence may be indirect: by showing the concept was viable, it may have subtly encouraged other developers to explore gamebook-roguelike hybrids, even if they never played Corremn’s specific game.

Conclusion: A Significant Step, Not a Definitive Journey

Warlock’s Mountain is a game that must be judged on two axes: historical significance and contemporary playability.

On the historical axis, it is immensely significant. It is a primary source document from the mid-2000s indie/roguelike scene, capturing a moment when developers were aggressively experimenting with genre hybrids. It is the first known attempt to directly apply roguelike procedural generation and real-time tactical combat to the Fighting Fantasy license, a creative leap that reinterpreted a narrative gamebook as a systems-driven challenge. For scholars of game adaptation, it is a perfect case study in mechanical translation versus experiential fidelity. It chose the latter at the expense of the former, proving how difficult it is to capture the feel of a choose-your-own-adventure in a random dungeon.

On the axis of playability, it is a relic. Its graphics are bare, its balance likely unforgiving and sometimes silly, its narrative almost non-existent. The thrill of the original book—feeling the weight of a single dice roll that could end your hero’s life—is replaced by the monotony of repeating the same tactical steps in a different-shaped room. The “hack-n-slash romp” described in its own MobyGames blurb feels more like a “hack-and-wait” due to probable combat slog. It is not a game I can recommend to anyone seeking an engaging experience today. Its value is purely as a museum piece, a download to be run once for curiosity’s sake, to appreciate the ambition constrained by a seven-day clock and a roguelike toolkit.

Its ultimate verdict in video game history is that of a crucial prototype. The far superior, commercially released adaptations by Tin Man Games (which explicitly cited Russ Nicholson’s art and the board-game feel) and Big Blue Bubble learned from the ideas Warlock’s Mountain stumbled upon: that classes could work, that tactical grid combat could be fun, that the mountain should feel treacherous. But they wisely abandoned its procedural core, returning to the authored, fixed dungeon that is the soul of the gamebook. Warlock’s Mountain proved you could make a roguelike out of Firetop Mountain. The follow-up projects proved you shouldn’t—that the treasure was in the mountain’s fixed, deadly design, not in its random caves. In the end, Corremn’s 2006 creation is not the definitive way to play The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, but it is an essential, humble footnote in the long quest to find one.