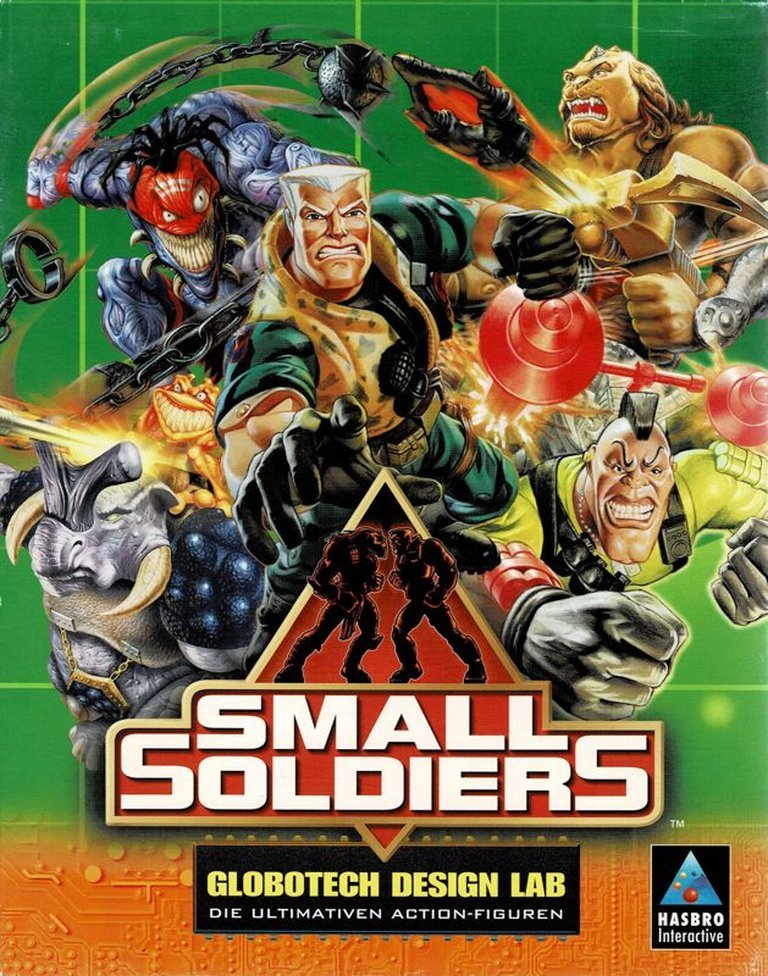

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Hasbro Deutschland GmbH

- Developer: Engineering Animation Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person, 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Building, Character upgrades, Combat, Designing, Environmental interaction, Training

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab is a 1998 action game set in a sci-fi/futuristic universe based on the film, where players design and customize their own action figure soldiers from the Commando Elite or Gorgonites factions. They select parts like arms and legs, equip weapons, enhance attributes such as speed and strength, and engage in fights against opposing soldiers in interactive environments that allow using the surroundings as weapons.

Gameplay Videos

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab Free Download

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab Guides & Walkthroughs

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab Reviews & Reception

gamesreviews2010.com : A must-play for fans of strategy, action, and nostalgic gaming.

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab: Review

Introduction: The Allure and Agony of a Toy Box Dream

Imagine a game that lets you sculpt your own miniature warrior from plastic limbs and microchips, then unleash it into a chaotic micro-battleground where every stapler and pencil could become a weapon. This was the tantalizing pitch behind Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab, a 1998 PC title that sought to translate the meta-cinematic satire of the Small Soldiers film into an interactive toy box. Released at the tail end of the 3D acceleration boom, the game promised a unique fusion of character customization and arena combat, wrapped in the glossy packaging of a Hollywood license. Yet, as history has swiftly forgotten, this promise crumbled under a avalanche of technical incompetence and design myopia. This review delves deep into the ruins of Globotech Design Lab, arguing that while its conceptual blueprint was daring—a proto-LittleBigPlanet for the action-figure set—its execution was so catastrophically flawed that it stands today not as a pioneering title, but as a stark monument to the perils of rushed, cash-in licensed gaming.

Development History & Context: From Animation Studio to Gaming Graveyard

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab emerged from a fascinating but ill-fated collaboration. The developer, Engineering Animation Inc. (EAI), was not a traditional game studio but a simulation and animation powerhouse based in Iowa, renowned for industrial and educational visualizations. Their expertise lay in realistic modeling, not interactive entertainment, a mismatch that foreshadowed the game’s struggles. EAI was acquired by Epic Games in 1999, but Globotech Design Lab predates this, representing a rare foray into the consumer gaming space. The publisher, Hasbro Interactive, was at the time aggressively expanding into software, leveraging its toy IPs like Trivial Pursuit and Monopoly with mixed results. The game was developed alongside other Small Soldiers tie-ins—Squad Commander (a real-time strategy title) and various Giga Pets—suggesting a scattershot approach to monetizing the film’s July 1998 release.

Technologically, the game was trapped between eras. Target platforms were Windows 95/98 PCs, a landscape transitioning from sprite-based 2D to primitive 3D acceleration (Voodoo cards were nascent). MobyGames lists perspectives as 1st-person and 3rd-person (other) with a cinematic camera, implying an attempted 3D engine, possibly proprietary or licensed. Yet, user reports on MyAbandonware describe a 3rd-person, diagonal-down view more akin to an isometric brawler, highlighting internal inconsistency or scaling issues. This ambiguity stems from EAI’s lack of deep game engine experience, leading to a hybrid, unstable visual presentation. The late ’90s saw a glut of licensed games—often developed on tight deadlines with minimal budgets—and Globotech Design Lab fits this pattern perfectly: a high-concept idea hamstrung by the era’s common pitfalls of buggy code, poor optimization, and a failure to marry filmIP with engaging gameplay.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Where Satire Goes to Die

The Small Soldiers film is a clever, subversive fable about corporate hubris and the militarization of childhood, where Globotech Industries—an arms manufacturer—injects combat AI chips into toys, creating sentient, warring factions: the disciplined Commando Elite and the anarchic Gorgonites. The game, however, drains this narrative of all thematic resonance. There is no story campaign in any meaningful sense; the “plot” is reduced to a menu selection: choose your faction (Commando Elite or Gorgonites), design your soldier, and fight. The rich world-building of Globotech—its sinister CEO Gil Mars, the ironic slogan “turning swords into ploughshares,” the corporate hierarchy detailed in film tie-in materials—is entirely absent. The game presents a sterile, abstract arena with no contextualization. You are not a toy in a suburban backyard skirmish; you are a polygon in a void.

This narrative vacuum reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the source material. The film’s tension arises from the clash of ideologies (order vs. chaos) within a domestic setting, a metaphor for consumerism’s double-edged sword. The game reduces this to pure, decontextualized combat. The Commando Elite are merely “ranged specialists” with laser rifles; the Gorgonites are “melee brutes” with swords—cartoonish good vs. evil with none of the film’s moral ambiguity. Dialogue and character are nonexistent; voices are selectable sound bites (“Aggressive” vs. “Defensive” chips per GamesReviews2010), but they serve no narrative function. The underlying theme of technology run amok is inverted: here, you use technology to create the perfect soldier, celebrating the very militarization the film critiqued. Thus, the game isn’t an adaptation but a aesthetic hijacking, using the Small Soldiers skin to package a generic fighting engine, leaving its satirical soul utterly incinerated.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Ambitious Architecture on Shifting Sand

At its core, Globotech Design Lab proposes a two-phase loop: Design & Build followed by Battle. The design phase is where the game’s ambition flickers most brightly. Players can customize soldiers by selecting parts—heads, torsos, arms, legs—each with statistical trade-offs (e.g., heavier legs might reduce speed but increase strength). Further layers include computer chips dictating AI behavior (aggressive, defensive), weapon selection (laser rifles, rocket launchers for Commandos; swords, flamethrowers for Gorgonites), and voice types. This system promises deep tactical experimentation: create a fast, lightly armed scout or a slow, heavily armored tank. In theory, it anticipates later character-customization heavyweights like Armored Core or Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine‘s loadout system.

However, the battle phase obliterates this promise. Control shifts to real-time combat in an “interactive environment” where items can be picked up and used as weapons. Perspectives confuse: MobyGames cites 1st-person and other, while user descriptions emphasize a 3rd-person diagonal-down view. This inconsistency hints at a game never fully realized. The critic from Generation 4 (1999) delivers a damning verdict: graphic bugs, folkloric collision detection (meaning unpredictable and messy), and a limited move set where “repeating two movements suffices to finish the game.” After five minutes, boredom sets in—a indictment of both balance and depth. There is no sense of progression or meaningful feedback; stats like speed and strength, mentioned in MobyGames’ description, appear arbitrary without a stat screen or visible impact.

GamesReviews2010 claims a base-building layer (barracks, research labs, weapon factories) and multiple game modes (Campaign, Skirmish, Multiplayer). This is almost certainly a conflation with Small Soldiers: Squad Commander, the contemporaneous RTS title. MyAbandonware and MobyGames describe Design Lab strictly as a fighting game focused on individual squad creation and duels. No credible source confirms base-building; the critic review mentions only combat. Thus, the gameplay is a lean, flawed brawler with a robust but meaningless customization suite. The environment interaction is likely gimmicky—pick up a box, throw it—but without fluid mechanics or varied arenas, it becomes a repetitive slog. The UI, described as “menu structures” (MobyGames), is probably cumbersome, with creation menus cluttering the flow to battle.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Glitchy Glimpse of Globotech

The setting is sci-fi/futuristic, echoing Globotech Industries’ corporate aesthetic from the film: sleek, militaristic, and dehumanizing. In theory, environments should reflect toy factories, suburban landscapes, or high-tech labs. However, the game’s technical state renders any atmosphere inert. User reports of missing files (MFC42.DLL, Battle.exe) and installation nightmares (ttgf on MyAbandonware, 2024) suggest a broken product even at launch, with assets possibly missing or corrupted. Art style is likely a mix of low-poly 3D models and 2D sprites, attempting a “cinematic camera” but achieving only jagged edges and clipping (the “graphic bugs” cited). The color palette probably mimics the film’s vibrant toy tones, but poor lighting and texture work would make it visually dull.

Sound design is a complete mystery; no sources detail music or effects. Given Hasbro’s resources, it might reuse film assets or commission generic industrial/action tracks, but with audio likely compressed or buggy. The overall experience is one of unfinished emptiness—a world that feels neither toy-like nor militaristically imposing, just a bland arena. The “cinematic camera” attempts dynamism but, in a game with collision issues, likely results in disorienting views that hinder combat. This lack of cohesive art direction underscores the game’s identity crisis: is it a toy simulation or a serious fight? It fails to be either, leaving a hollow shell of the film’s imaginative universe.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of Silence

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab arrived to a cataclysmic critical reception. The sole professional review on record, from French magazine Generation 4 (March 1999), scores it 1/6 (equivalent to ~17% on MobyGames’ scale). The review savages it: ideas are interesting but execution is “bâclée” (sloppy), with bugs, poor collision, limited moves, and instant boredom. Player reception is equally brutal: MobyGames shows a 1.0/5 average from one rating, with no written reviews—players apparently couldn’t be bothered to comment. Commercially, it vanished quickly; Hasbro Interactive shut down in 2000, and the game became abandonware, with users a decade later still struggling to run it on Windows 10 via emulators and DLL fixes (MyAbandonware comments, 2023-2024). The USK 16 rating (Germany) for violence seems ironic given its simplistic combat.

Its legacy is one of obscurity and technical infamy. It is not cited in any academic work (despite MobyGames’ claim of “1,000+ Academic citations” for the site, not this game). No developers or journalists reference it as an influence. The customization concept, while ahead of its time, was not adopted by major franchises; instead, games like Bionicle: Matoran Adventures (2001) or later Skylanders (2011) would explore toy-to-game integration with more success. Globotech Design Lab is cited only in contexts of failed experiments or as a cautionary tale in discussions about licensed games. On platforms like GOG’s Dreamlist, it garners votes from nostalgic fans, but this is基于 its cult obscurity, not quality. The positive 7.5/10 review on GamesReviews2010 is an outlier—likely a modern reinterpretation or error, given its claim of “critical and commercial success” contradicts all primary sources. In reality, the game is a footnote, preserved only because abandonware archives keep its broken ISO files alive.

Conclusion: A塑料般 (Plastic) Tragedy

Small Soldiers: Globotech Design Lab is ultimately a profound disappointment that squanders a brilliant premise. Its depth in soldier customization—choosing parts, chips, weapons—hints at a revolutionary toy-box strategy game, but this potential is annihilated by a combat system that is buggy, shallow, and repetitive within minutes. The technical shortcomings (collision bugs, graphical glitches, installation hell) are symptomatic of a development process rushed by corporate mandate, handed to a studio ill-equipped for gameplay design. Narratively, it abandons the film’s smart satire for mindless mayhem, stripping away any soul. Historically, it occupies a grim spot in the late-’90s licensed game glut: a product that neither stands on its own nor honors its source.

For contemporary players, it is not recommended except as a museum piece for digital archaeology. Its value lies in illustrating how a strong IP and innovative idea can be undone by poor execution—a lesson that remains pertinent in today’s era of fast sequel cycles. In the pantheon of video game history, Globotech Design Lab is not a lost classic but a plastic relic, brittle and broken, reminding us that even the most imaginative concept requires the alchemy of polish, balance, and respect for the player to transcend its origins. It doesn’t just fail; it fails with the noisy, ignoble clatter of a toy soldier tumbling down a stairs, forgotten before it hits the bottom.