- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, Anuman Interactive SA

- Developer: X-bow Software

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Car customization, Career mode, Damage system, Drifting, Upgrades

- Setting: Seaside, Summer, Sunny

Description

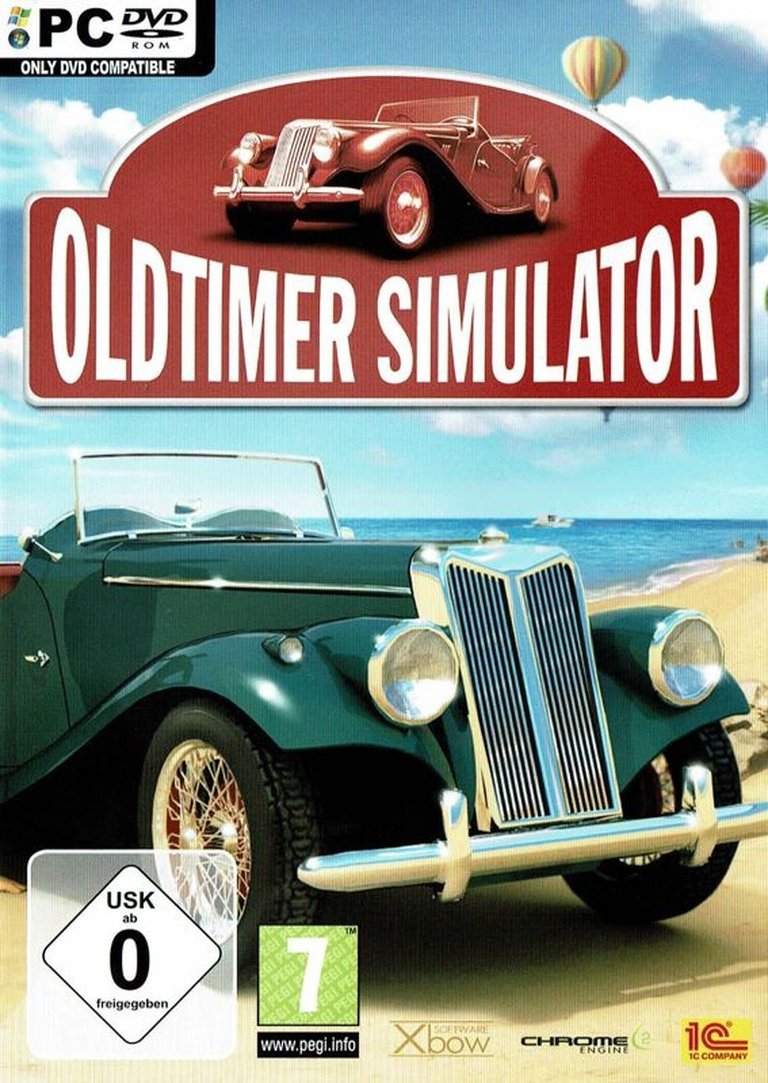

Classic Car Racing is a racing simulation where players compete with vintage automobiles from the 1940s to 1960s across vibrant, sunny summer environments often set near the sea with cheering spectators. The game features dual modes—arcade for casual play and simulator for realistic handling—alongside a career mode, car customization through upgrades and tuning, and third-person racing against AI opponents on diverse tracks.

Gameplay Videos

Classic Car Racing Free Download

Classic Car Racing: A Chronically Underrated Relic of the 2000s Racing Boom

1. Introduction: The Allure of Chromed Steel and Faded Dreams

The image is iconic: a gleaming Jaguar XK120 or a curvaceous Cadillac Eldorado slicing through sun-drenched coastal roads, the roar of an inline-six engine echoing off cliffs, the scent of salt air and hot asphalt. For automotive enthusiasts, the post-war classics of the 1940s through the 1960s represent a pinnacle of design—a blend of elegance and raw, unrefined power. Classic Car Racing (2007), developed by Russia’s X-bow Software and published by 1C Company/Anuman Interactive under titles like Oldtimer Simulator and Rétro Rally, promised exactly this: a pilgrimage into that golden age. It wasn’t just another simulation; it was an attempt to bottle nostalgia, to let players feel the tactile feedback of non-power-assisted steering and the visceral thrill of a drum brake’s fading authority. Yet, as the decades have piled on, the game has become a fascinating archaeological specimen—a title that embodies the ambitious yet often flawed spirit of mid-2000s PC racing. It arrived at a crossroads, where realistic sims were becoming deeply intricate and arcade racers were embracing open worlds. Classic Car Racing aimed for a niche in between but ultimately became a cautionary tale about theme without soul, mechanics without magic, and a profound missed opportunity to make vintage automobiles feel truly historic.

2. Development History & Context: A Studio Out of Time and Place

To understand Classic Car Racing, one must first look at its creator, X-bow Software. This Russian studio was better known for gritty, hardcore fare: the World War II real-time tactics of the Men of War series, the survival horror of Cryostasis, and the off-road militarism of 4×4 Hummer. Their engine of choice, the Chrome Engine (a proprietary 3D suite), was built for destructible environments and ballistic physics, not the nuanced rubber-compound modeling required for a title celebrating the nuanced handling of a 1955 Mercedes 300SL. The 2007 release date is pivotal. The racing genre was in a state of flux. Polyphony Digital’s Gran Turismo 4 (2004) had just redefined automotive curation, while Turn 10’s Forza Motorsport (2005) was building a formidable franchise on Xbox. Arcade-style titles like Burnout Paradise (2008) were on the horizon, championing spectacle. Classic Car Racing landed in a no-man’s land: too sim-like in its tuning options for pure arcade fans, yet too superficially “arcadey” in its track design and AI for hardcore simmers. It was caught between the meticulous historicity of a GT Legends (2005) and the vibrant, accessible fun of an OutRun 2 (2003). Developed in Russia, a region with a strong racing sim tradition (Eutechnyx, Bugbear) but a quieter voice in the global conversation, the game felt like a passion project from a team whose core competencies lay elsewhere—a heartfelt but technically uneven tribute to a era they clearly admired but could not fully simulate.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Ghost in the Machine

Here lies the game’s most profound and telling failure: a catastrophic lack of narrative and thematic cohesion. The premise is pure fantasy: why are we racing a 1949 Oldsmobile 88 against a 1965 Ford Mustang on a sun-baked Mediterranean circuit? The game provides no context. There is no career arc, no story, no rivalries, no sense of progression beyond a simple points-based championship. One review from games.mail.ru poignantly notes the absence of even a “minimal scenario,” a “lack of a global goal.” This vacuum is fatal for a theme as rich as classic automobiles.

A title like Test Drive Unlimited (2006) understood that cars are not just polygons; they are characters with histories, statuses, and identities. It wove a narrative of luxury living and social climbing around its vehicle roster. Classic Car Racing offers fourteen cars from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, but they are presented as anonymous assets in a shop catalog. There are no “mini-biographies” that connect the player to the engineering marvels they pilot. The “aristocratic” essence, the “exquisiteness” that an Absolute Games critic pined for, is entirely absent. You do not feel like a collector, a connoisseur, or a historian. You feel like a test driver in a generic, sunny locale.

The tracks, while colorful and coastal, reinforce this emptiness. They are picturesque but generic—”colourful summer environments often close to the sea where lightly clad sun bathers cheer on the drivers,” as the official description states. This isn’t Monterey in 1958 or the Amalfi Coast in 1962; it’s a placeless, timeless resort. The thematic promise of “classic car racing” is betrayed by a world that feels utterly contemporary and anonymous. The game’s greatest irony is that in its attempt to celebrate the past, it creates a world with no past whatsoever. The cars drift through a vacuum, and the player is left with nothing but the hollow repetition of laps. Where is the rust, the patina, the sense that these machines have been resurrected from a barn find? Where are the period-correct billboards, the fashions of the spectators, the very feeling of a bygone era? Classic Car Racing has the what but none of the why or when, and this thematic void ultimately dwarfs any mechanical merits it might possess.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Competent but Constrained

Beneathing the thematic void lies a functional, if unspectacular, driving model. The game offers a dual-mode structure: Arcade and Simulator, selectable at the start and purportedly adjusting difficulty. In practice, the distinction feels more like a slider for AI aggression and car stability than a fundamental shift in physics. The core loop is a career mode comprising a mere twelve races. This brevity is a repeated critical refrain; as the Out of Eight review states, the game is “short… only twelve races fly by.” The championship structure is simple: finish races to earn money, use money to unlock five of the fourteen total cars and to purchase upgrades from a virtual shop.

The upgrade system is robust on paper—engine, suspension, brakes, transmission, body, tyres, and paints—and includes granular tweaking options: suspension height/stiffness, brake bias, steering angle, gear ratios, and gearbox type (auto, semi-auto, manual). This suggests a desire for mechanical depth. However, this system is critically undermined by two factors. First, as the Out of Eight critic astutely observed, “some of the upgrades were stolen from another racing game and some of the setup options are pointless as all of the races take place on pavement.” There is no off-road, no wet track (all races are in “sunny… environments”), making certain setup adjustments irrelevant. Second, the AI does not engage with these systems in a believable way. While critics note the AI drivers are “capable opponents that exhibit human-like behaviors” and will aggressively fight for position, they do not suffer mechanical failures or benefit from upgrades in a dynamic way. The tuning feels cosmetic, a checklist rather than a meaningful strategic layer.

The damage model is present: components can be damaged, and excessive damage can force retirement. Yet, as the Absolute Games review savages, the damage is “not convincingly” rendered and “uninteresting to watch even in well-done replays.” Repairs happen magically during the race, stripping away consequence. The drifting mechanic awards bonus points, a clear arcade holdover, but it feels disconnected from the period theme—powersliding a 1948 Ferrari 166MM is a cinematic fantasy, not a historical reality.

The interface is clean but minimal: speed, gear, position. The third-person camera is the only perspective, a missed opportunity for the immersive dash-cam views that defined later sims. The vehicle lineup is the star—fourteen classics across three decades—but only five are available from the start, forcing grind-repetition to unlock the rest. This economy feels thin, offering little long-term incentive. Ultimately, the gameplay is a paradox: it provides the tools for simulation (tuning, gearboxes) but strips away the context that gives those tools meaning (variable conditions, a meaningful championship narrative, consequences). It’s a mechanical sandbox with no castle to build.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Postcard Without a Stamp

Visually, Classic Car Racing is a product of its time and engine. The Chrome Engine renders bright, saturated environments. The tracks are undeniably pretty—winding coastal roads, palm trees, azure seas, and crowds of sunbathers. The color palette is aggressively cheerful, leaning into a “holiday postcard” aesthetic. The car models themselves are competent, capturing the iconic silhouettes of vehicles like the Chevrolet Bel Air or the Volkswagen Beetle, but they lack the material fidelity—the gleam of chrome, the texture of leather, the subtle rust spots—that would sell their vintage status. There is a flatness to the lighting that fails to make these machines feel like precious artifacts. The damage modeling, as noted, is unconvincing; dents and scratches appear as generic texture swaps rather than deformations, lacking thecrumple-zone realism of contemporaries like Race Driver: Grid (2008).

The sound design is functional but unmemorable. Engine notes are generic growls and rumbles, failing to capture the distinct symphony of a straight-eight, a V12, or a flat-four. Tire squeal and wind noise are present but unremarkable. The soundtrack, composed by X-bow Studio’s Sergey Perekrestov and others, is a forgettable mix of light rock and ambient loops that does nothing to enhance the period mood. It is not offensive, but it is completely inessential.

The world-building is the greatest victim of this aesthetic approach. The “jolly good fun” atmosphere of sun-soaked beaches is tonally at odds with the gravitas of classic car culture. These vehicles are museum pieces, racing trophies, yet they are placed in a world that feels like a generic OutRun clone. There is no sense of history, no decaying grandeur, no juxtaposition of old and new. The game’s world is a timeless, placeless resort that erases the very era it seeks to celebrate. It presents the cars as vibrant, modern toys rather than relics. This is not an evocative recreation of the golden age of motoring; it is a sanitized, sun-bleached Themepark™ version, where the only “classic” element is the superficial styling of the vehicles themselves.

6. Reception & Legacy: A Whisper in the Storm

Upon release, Classic Car Racing was met with a chorus of polite shrugs. The Metacritic-equivalent average from three critics on MobyGames is 65%, a score that screams mediocrity. The Out of Eight (75%) review was the most charitable, praising the “good” graphics, “capable” AI, and “solid driving” physics, but immediately damning it with the faint praise of being a short, single-player-only diversion. The Russian press was harsher. games.mail.ru (60%) acknowledged the “great selection of retro cars” and “wonderfully beautiful coastal tracks,” but bemoaned the “unrealistically nimble” AI and “completely unconvincing” special effects. Absolute Games (59%) delivered a scathing verdict: the game “lacks not only sporting excitement… but also an air of aristocracy, of exquisiteness.” It posited that in an era with Test Drive Unlimited, there was “much that could have been done with such material,” and concluded bleakly: “In what way is ‘Classic Car Racing’ different from ordinary unremarkable arcades? Nowhere.”

Its commercial performance is obscure, but its inclusion in budget compilations like the “1C Complete Collection” (2010) suggests it found its audience in discount bins. Its legacy is virtually non-existent. It did not spawn sequels. It is rarely, if ever, cited in “best racing games of all time” lists or retrospectives. It occupies a quiet corner in the vast Wikipedia list of racing games, a title with no series, no cult following, and no discernible influence on subsequent design. While the mid-2000s saw the rise of seminal franchises ( Forza, DiRT, Need for Speed reboots) and the maturation of simulation (rFactor, Live for Speed), Classic Car Racing was an island of singular, uncultivated vision that failed to connect. It represents a lost genre possibility: the dedicated “classic car sim.” Titles like GT Legends (2005) had already trod this ground with greater authenticity and depth, using period-correct tracks and physics. Classic Car Racing’s approach was too gamified for purists and too hollow for arcade fans. It is a historical footnote—a game that asked a compelling question (“What if you could only drive vintage cars?”) but provided a thoroughly unsatisfying answer.

7. Conclusion: A Well-Intentioned Curio, Doomed by Its Own Emptiness

Classic Car Racing is not a bad game by the standards of 2007. Its core driving is competent, its car selection is a genuine point of interest for vintage enthusiasts, and its technical underpinnings are stable. Yet, it is a catastrophically incomplete experience. It is a chassis with an engine but no steering wheel, a body with no frame. The disconnect between its theme (the romance of classic automobiles) and its execution (a generic, sunny arcade-sim hybrid) is its defining, fatal flaw. It provides the toys—the beautiful, historically significant cars—but strips away the context that gives them meaning: the story, the atmosphere, the stakes, the very feeling of the past.

In the grand pantheon of racing games, it holds no significant place. It did not innovate mechanically, it did not capture a cultural moment, and it left no progeny. It is a curio, a testament to the ambition of a studio stepping outside its comfort zone, but also a stark lesson in the importance of thematic integrity. A great racing game about classic cars should make you feel the weight of history, the vulnerability of primitive engineering, the sheer audacity of speed before electronic aids. Classic Car Racing makes you feel only the sun on your face and the repetition of the track. It is a game forever stuck in neutral, a beautiful, chromed-out phantom that promised a journey back in time but never left the starting line. For historians, it is a perfect case study in potential squandered. For players, it is a forgotten rental, a ghost in the machine of a genre that roared right past it.