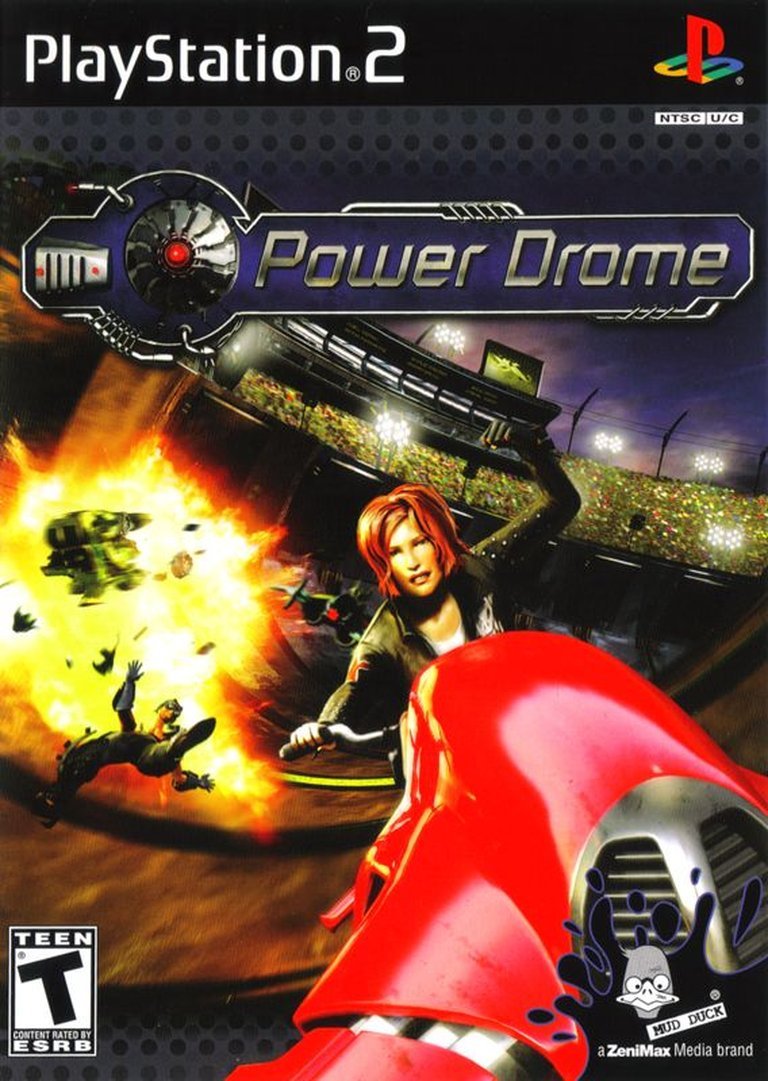

- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Windows, Xbox

- Publisher: Evolved Games, Noviy Disk, Xicat Interactive Corporation, ZeniMax Media Inc., ZOO Digital Publishing Ltd.

- Developer: Argonaut Sheffield

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 1st-person / Behind view

- Game Mode: Co-op, LAN, Single-player

- Gameplay: Racing, Unlockables

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 51/100

Description

Power Drome is a futuristic racing game that updates the classic 1989 Amiga and Atari ST title. Set in a sci-fi world, it features 12 unique riders competing in the fastest and most dangerous racing sport, with breathtaking speeds reaching 1,000 miles per hour. Players engage in pure racing action through single-player and multiplayer modes, including split-screen and system link, across dynamic tracks emphasizing speed and competition.

Gameplay Videos

Power Drome Free Download

Power Drome Reviews & Reception

ign.com (51/100): A futuristic Formula One game that offers 12 different characters, 24 circuits, eight environments, and online competition.

Power Drome Cheats & Codes

Sony PlayStation®2

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| B4336FA9 4DFEFB79 61D5614C B2254030 59BE1936 B2944258 D9B31969 AF9C2DF9 | Enable Code (Must Be On) |

| 058E11D8 76CE5B9D | Infinite Boost (Even When Empty) |

| 43AA24D2 C71C8EB7 | Infinite Boost (Upon Receiving 1) |

| 7DCF80C7 AC7531D6 | Access All Gallery/Movies |

| E4B122D4 354E81A3 | Have Event Icon |

| 8D50BB26 36F4B25A | San-Kei Speedway |

| 6D261C78 F06C2552 | Have Event Icon |

| AD46BC15 C4E32099 | San-Kei Outfield |

| E3CC3C2E C6269C75 | Mata Wai Ocean Dam |

| 155219DA 4935127C | Acer Naim Orbital |

| 247B6F00 BC9E0EC2 | Have Event Icon |

| A46CB624 35D8783D | Imperial Diebak Silo Complex |

| DB8A3197 C43DE0D9 | Have Event Icon |

| 8A7CC3A2 57CD53DD | Challenge Strip |

| 4E65E255 FC78E295 | Have Event Icon |

| B19A3272 8C70E0CC | Mata Wai Plains |

| BD52C8DD 6B83F46A | Imperial Diebak Silo Complex |

| DDD1C9EA F696FEC6 | Caldera Circuit |

| DFC739EC 0FF834FD | Have Event Icon |

| 9C755102 C87D2362 | San-Kei Speedway |

| 413E9691 16025706 | Have Event Icon |

| 5FF22BEB 5D167AAE | Soomis Forest |

| 43333A21 580A2BD2 | Have Event Icon |

| 42BEF3AD 6E668AC0 | Imperial Diebak Silo Complex R |

| CCC2E7F4 374277E1 | San-Kei Outfield R |

| 1057EF03 ED9FA2AC | Soomis River Run |

| 2D1EF9FA C9E945F5 | Have Event Icon |

| B6D711A7 42EEAA48 | Challenge Strip 2 |

| BD57F1E7 5406EBF3 | Have Event Icon |

| CB1C3C63 C6867EB5 | Mata Wai Ocean Dam |

| 470048F9 0709761E | Have Event Icon |

| D353ECCD 1E0D3055 | San-Kei Outfield |

| 54278908 D96EE674 | San-Kei Speedway |

| 56EEEA09 8844D791 | San-Kei Outfield R |

| B543EB2B EB617757 | Have Event Icon |

| 28B10C62 7912485F | Mata Wai Plains R |

| D3EE3068 7D70B7B7 | Have Event Icon |

| 1E0637A5 3631662A | Imperial Diebak Silo Complex |

| 8D54162E 46055933 | Have Event Icon |

| 23E31977 5A9B461B | Soomis Forest |

| E572B80B DF1D81C8 | Acer Naim Substructure |

| EF8C24A7 1A5AA1ED | Have Event Icon |

| AC9AC7B1 DCB69FC1 | Challenge Strip 3 |

| 3D9FE8EB 92EF85D0 | Have Event Icon |

| FE851377 D1C02C7B | Mata Wai Plains |

| F27E17E0 D26950C3 | Have Event Icon |

| 7F62499A 53529677 | Imperial Diebak |

| 7DAD4DC2 2D3E6C60 | Caldera Circuit |

| 744353DB 0A757968 | Soomis Forest R |

| 26D3B245 83C0AEA8 | Acer Naim Orbital |

| 41BB3A1B D75CC940 | Have Event Icon |

| 5ABCE119 BC06B936 | Caldera Circuit R |

| 19D6D675 A19DEE2B | Acer Naim Orbital |

| FCB5D9A1 F86A58C1 | Mata Wai Plains |

| 658EDD9F 0AB34323 | Soomis Forest R |

| 83159FFF D8FD5B31 | Have Event Icon |

| 36D97C04 0045A828 | Challenge Strip 4 |

| 080A482F 8C6BD794 | Have Event Icon |

| 07BD278B 85A7FA32 | Imperial Diebak R |

| 75F3D5D3 179B3F81 | Acer Naim Substructure R |

| C30BE14F 8A18CCB8 | San-Kei Speedway |

| B509BC51 A60F58EB | Have Event Icon |

| 171AB6A3 E731540A | San-Kei Outfield |

| C173729C 68730488 | Have Event Icon |

| XDGD-XRT2-FBFZ8 | Master Code – Must Be On |

| XK1W-J55W-026Y1 | Master Code – Must Be On |

| 7BPW-G176-EKZ4T | Infinite Boost |

| 073R-PC4F-VMFF1 | Infinite Boost |

Xbox

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| hold R + L triggers and press black, white, X, X, Y | Unlock Tache Telpan XSU-K0cc Racer |

| hold down the Y button before selecting the vehicle selection screen | Use Same Vehicles In System Link |

Power Drome: A Relic of Pure Speed in a Genre Running Out of Track

Introduction: The Ghost in the Racing Machine

In the pantheon of futuristic racing games, the Names That Must Not Be Spoken—F-Zero, Wipeout— loom like monoliths. Yet, tracing the genre’s DNA back through the mists of the late 1980s reveals a quieter, earlier ancestor: Powerdrome. The 2004 remake, Power Drome, is not a resurrection but a curious anachronism. Released into a landscape already dominated by the baroque weaponized chaos of Wipeout Fusion and the blistering, arcade-perfect spectacle of F-Zero GX, Argonaut Sheffield’s title arrived like a time capsule from a simpler, more brutal vision of the future. It is a game defined by its contradictions: a technically uneven budget title underpinned by a purist, skill-first design philosophy that feels both archaic and refreshingly direct. This review will argue that Power Drome is a flawed but significant historical artifact—not for its execution, but for its steadfast, almost stubborn, commitment to “racing in its purest form” at a time when the genre was sprinting in the opposite direction.

Development History & Context: From Amiga Cult Classic to Sixth-Generation Footnote

The story of Power Drome begins not in 2004, but in 1988. Designed by Michael Powell at Argonaut Games (the UK studio famed for Star Fox’s Super FX chip), the original Powerdrome on Atari ST/Amiga was a niche, critically respected title. Its legacy rests on two pillars: a novel, mouse-sensitive control scheme that simulated a vehicle’s roll and pitch for turning (a deliberate departure from standard “yaw” steering), and a tactical layer involving atmospheric gas filters and fuel types. This was racing as a harsh, survivalist sport, not a glamorous spectacle.

The 2004 remake, developed by Argonaut Sheffield—a studio led by Powell and Technical Director Glyn Williams—was announced in May 2003. It faced a brutal development context. The original 3D racing boom of the early 2000s (WipEout 3, F-Zero X) had evolved into a high-definition, effects-laden arms race on the newly launched Xbox and PlayStation 2. Simultaneously, the genre was bifurcating: one branch leaned into combat and power-ups (Rollcage, Atomic Race), the other into ultra-polished, technical arcade-sim hybrids (Project Gotham Racing, Gran Turismo). Power Drome was caught between eras.

Financed and published by a series of budget-focused entities—Mud Duck Productions (a ZeniMax/ZOO Digital subsidiary) in North America, Evolved Games and ZOO Digital in Europe—the project was inherently constrained. As noted in the credits, the team was lean (56 developers), and the game was positioned at a $29.99 price point, immediately marking it as a value proposition rather a premium blockbuster. The decision to drop the original’s gas filter/fuel customization, as cited by TeamXbox, was a decisive one: focusing purely on racing skill meant streamlining for a new audience that likely found the 1988 mechanics obtuse. This was a remake not of preservation, but of reinterpretation—a “pure” racer for a time when purity was a niche marketing angle.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Sport is the Story

To call Power Drome narratively thin would be a profound understatement. It possesses no cutscenes, no story mode, no overarching plot. The narrative is entirely diegetic, embedded in the manual’s lore and the game’s aesthetic: “12 riders risk all each with their own personality, racing style, and friends or foes.” The theme is unmistakable: brutal, high-stakes future sport. This is not a galactic league (Wipeout) or a royal exhibition (F-Zero). It is a gladiatorial contest where the machine is an extension of the pilot’s will, and death is an implicit footnote.

The “personalities” exist only in name and subtle visual differences between the 12 selectable “blades” (anti-gravity hovercraft). The Neoseeker description mentions archetypes like “decommissioned war droids” and “robot political activists,” but these are flavor text, not developed characters. Dialogue is nonexistent; communication is through the violent physics of collision and the silent language of the leaderboard. This vacuum of narrative is, in itself, a statement. It enforces the game’s core thesis: the only story that matters is the one written in lap times and overtakes. The track environments—from neon-drenched cityscapes to stark industrial zones—suggest a world where these races are illegal street challenges or corporate-sponsored death matches, but the game never commits. It is a pure sporting arena, stripped of all context save the imminent, terrifying sensation of speed. The theme, therefore, is absolute, unadulterated velocity as the sole measure of worth.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Calculus of Control

Power Drome’s identity is forged in its control scheme, a direct descendant of the 1989 original’s mouse-oriented physics. Here, on a gamepad, the translation is jarring but deliberate. Turning is not achieved by simple left/right input. To navigate a right-hander, you must first roll the blade to the right (using the left analog stick horizontally), then pitch the nose up (using the stick vertically). This creates a banking, swooping motion that feels more like piloting a fighter jet than driving a car. The learning curve is, as Bordersdown noted, “initially brutal.” Misjudge the sequence, and you either understeer wide or over-roll into a wall. There is no traction- or speed-loss forgiveness; the game’s quoted “1,000 mph” speeds are not an exaggeration in feel.

This control system is the game’s great innovation and its greatest flaw. It demands a level of muscle memory and spatial reasoning that modern racers rarely require. There is no “assist” to soften it. Success is 100% on the player’s ability to internalize a complex, three-dimensional input model. For the dedicated, this yields immense satisfaction—mastering a track’s corners through precise roll-pitch coordination is a deeply tactile, physical accomplishment. For the casual player, it is an impenetrable barrier. This is racing as high-wire act, not sport.

The gameplay loop is spartan: select a rider (each with minor stat variances in top speed, acceleration, handling—though reviews suggest differences are subtle), choose a track (6 base layouts, multiplied by reverse/mirror variants to 24 unique routes), and race. Modes are limited to Championship, Single Race, Time Trial, and the aforementioned “Street Race” mode from Neoseeker’s feature list (one-on-one on obstacle-filled city courses). The conspicuous absence is weapons. Unlike its contemporaries, Power Drome offers no power-ups, no missiles, no shields. This is pure, unfiltered time attack competition. Your only tools are your line, your braking points, and your mastery of the roll-pitch mechanic. As TeamXbox phrased it, it’s “not an in-depth driving-sim,” but nor is it a “battle racer.” It occupies a desolate middle ground: a pure skills trial.

The UI is functional but dated, and the damage model—while praised for “realistic” panel buckling and smoke—has little impact on handling, serving mostly as a cosmetic failure state. Progression is linear: win championships to unlock more characters and events. The lack of any customization (vehicle tuning, part upgrades), explicitly called out by TeamXbox as “the biggest drawback,” reinforces the “pure skill” ethos but leaves players with little long-term investment beyond mastering the existing content. The multiplayer (split-screen on all platforms, System Link on Xbox, and now revived on Insignia servers) is the natural habitat for this design, turning the brutal skill gap into a tense, personal duel.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic of Velocity

Visually, Power Drome presents a stark, high-contrast sci-fi aesthetic. The tracks are built from clean, geometric shapes—neon pipes, sweeping metallic bridges, vast chasms lit by ambient glows. The environments are severe, almost minimalist, avoiding the busy, advertisement-stuffed futurism of Wipeout. This serves a functional purpose: clarity. At the quoted “1,000 mph,” the game’s art direction prioritizes readable track geometry and horizon lines over visual density. The sense of speed is achieved through a combination of a wide field of view, aggressive motion blur (a divisive effect), and a frantic, rushing parallax scroll on distant environments.

Critics were split. GameSpot praised “smooth sensation of speed and detailed environments,” while Games TM found it “left on the starting line” and IGN was dismissive. The truth lies in the performance. On PS2 and Xbox, the frame rate is generally stable, but the visual fidelity is undeniably of its budget era—low-poly models, basic texture work, and simplistic effects. The PC port, handled by Second Intention, introduced “self-shadowing, image-based lens reflections, depth of field,” as per the PCGamingWiki, offering a technically superior but still aesthetically dated experience. The art style is consistent but unambitious, evoking a late-90s PlayStation 1 aesthetic transposed to sixth-gen hardware.

The sound design is a similar mix of competence and criticism. The engine screeches are piercing and effective at conveying raw thrust. Collision sounds are meaty and satisfying. However, the soundtrack is widely panned as “lacklustre” (Wikipedia) and generic, consisting mostly of forgettable, driving electronic tracks that fail to establish the iconic identity of, say, Wipeout’s soundtrack. The “pilot’s voices” mentioned in the original 1988 review are absent here, which is likely a mercy. The audio successfully services the gameplay—it is loud, urgent, and clear—but it is not immersive. It is a tool, not an atmosphere.

Reception & Legacy: The Also-Ran with a Purist’s Heart

Power Drome’s launch reception was decidedly mixed, perfectly captured by its aggregate 63% (MobyGames) / 69 (Metacritic) score. The critical spectrum was wide:

- The Positive (~70-79%): Reviews from GameSpot (7.9), TeamXbox (7.3), and 7Wolf Magazine (7.4) championed its purity. GameSpot’s historical framing was key: “Argonaut lays some claim to genre husbandry.” They saw it as a competent, enjoyable racer that honored a lineage. TeamXbox explicitly recommended it for its $29.99 price and straightforward experience.

- The Middle (~60-68%): Worth Playing (6.5), Games TM (6.0), and PC Zone (6.0) found it “adequate” but unremarkable. The consensus was that it did nothing wrong enough to be bad, but nothing right enough to be essential. PC Zone’s verdict is telling: “a half-decent waste of a weekend.”

- The Negative (~40-51%): IGN (5.1) and Jeuxvideo.com (10/20) were scathing. IGN’s conclusion—that it “doesn’t deserve the effort” and to “save your energy for a deeper racing title”—epitomizes the mainstream consensus. It was compared unfavorably, always, to F-Zero GX and Wipeout, the genre kings of the era.

The commercial reality was that of a budget title. It was not a mainstream success but found a small audience, primarily on Xbox where its online multiplayer (via Xbox Live, now preserved on Insignia) and slightly better reception gave it a ranking of #484 on the Xbox MobyGames list. Its legacy is therefore dual:

- A Historical Footnote: It is the last, faint echo of the original Powerdrome’s design philosophy—the non-yaw, pure-control racing—in an era that had abandoned it. It preserves a specific, control-oriented branch of the genre’s family tree that otherwise went extinct.

- A “Could-Have-Been” Curio: Bordersdown’s review title says it all: “An entertaining title that could have been a classic.” Critics repeatedly noted that with more polish, a better soundtrack, and perhaps some riskier visual design, its core gameplay loop could have found a dedicated cult following. Instead, its technical roughness and brutal difficulty capped its appeal.

Its influence on subsequent games is negligible. The genre moved toward deeper combat (Redout), cinematic storytelling (Fast & Furious crossovers), or VR experiments. Power Drome’s “no weapons, pure line” philosophy was a dead end for commercial evolution. Yet, in the modern retro and speedrunning scenes, its unique control scheme and stripped-down design make it a fascinating object of study for those seeking a F-Zero-like experience without items or flash.

Conclusion: A Flawed Time Capsule for the Purist

Power Drome is not a great game. By any mainstream metric—graphical fidelity, narrative depth, accessibility, feature set—it falls short. Its environments are sparse, its soundtrack forgettable, its UI basic, and its difficulty curve a wall. Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to miss its peculiar, resilient value.

It is a purist’s relic. In an age where futuristic racers competed on the basis of weapon variety, track gimmicks, and cinematic presentation, Power Drome doubled down on a single, demanding pillar: the sheer, unadulterated joy of mastering an intricate, physics-based control system at ludicrous speeds. It asks for nothing but your time and focus, and for the player who invests that time, it offers a uniquely gratifying, skill-based victory condition unmediated by random power-ups or rubber-banding AI.

Its place in history is not that of a classic, but of a conscientious objector. It is a budget-priced, technically flawed manifesto for a simpler, more demanding vision of racing. For the historian, it is invaluable as a bridge between the mouse-controlled, simulationist Powerdrome of 1988 and the controller-slick, spectacle-driven racers of 2004. For the modern player, it is a curiosity—a game that feels both dated and refreshingly direct, a demanding challenge that rewards perseverance with a pure, unspoiled sense of speed.

Final Verdict: 6.8/10 – A deeply flawed, historically curious, and stubbornly pure racing game. It is not essential, but for the patient player seeking a F-Zero-style experience stripped of all ornaments, its brutal, rewarding core remains a compelling, if lonely, destination on the racing game map. It deserves respect for its conviction, if not its execution.