- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: CrypTool project

- Genre: Educational, Puzzle

- Perspective: Text-based / Spreadsheet

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Math logic, Puzzle, Strategy

Description

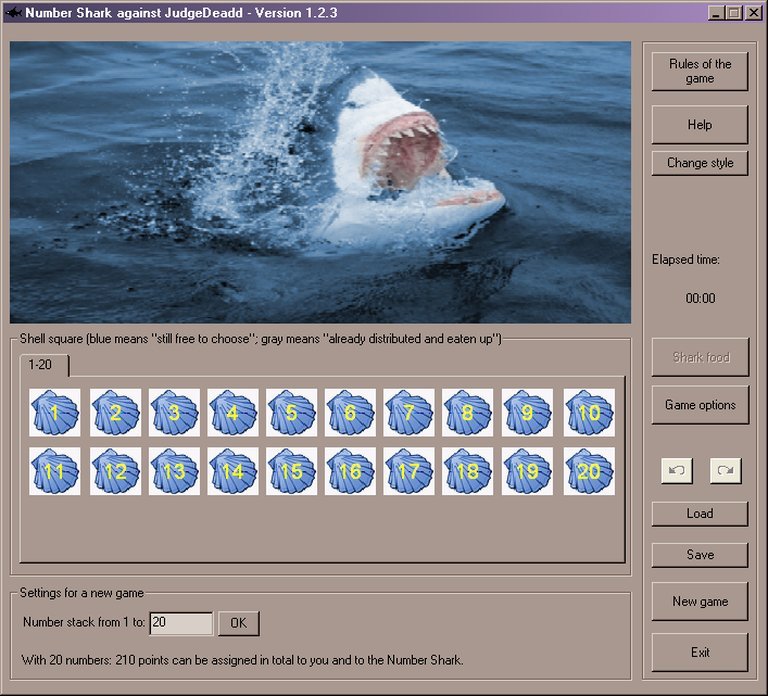

Number Shark is an educational puzzle game bundled with the freeware cryptographic program CrypTool, based on the ‘Taxman’ game concept. Players compete against a ‘Number Shark’ on a board of numbered shells, starting from 1 with adjustable counts. By selecting a shell, players earn its point value, but the shark immediately claims all remaining shells whose numbers are real factors of the chosen one; if no factors exist, the shark takes the selected shell itself. The game continues until all shells are gone, and victory is achieved by having a higher total score than the shark, all presented in a text-based, menu-driven interface.

Number Shark: Review

Introduction: The Calculus of a Cage Match

In the vast ocean of video game history, some titles are majestic leviathans, their wakes shaping entire genres. Others are peculiar, deep-sea creatures, obscure yet profoundly adapted to their ecological niche. Number Shark (2006) is unequivocally the latter. It is not a game about sharks in the traditional sense of chum-filled waters and frenzied feeding. Instead, it is a pristine, calculated duel of pure mathematics disguised as a simple shell-picking exercise. Bundled as a free curiosity within the serious cryptographic software CrypTool, Number Shark represents a direct, unadorned port of a brilliant mathematical game concept into a digital format. Its legacy is not one of commercial blockbuster status or critical acclaim, but of academic purity and efficient, elegant game design. This review will argue that Number Shark is a masterclass in minimalist game theory, transforming the abstract “Taxman” problem into a tense, agonizing, and deeply intellectual single-player experience where every choice echoes mathematically against the cold logic of its titular predator.

Development History & Context: From Hall of Science to Cryptographic Toolkit

To understand Number Shark, one must first understand its progenitor: Taxman. Invented by mathematician Diane Resek around 1969-1972 while at the Lawrence Hall of Science, Taxman was born from the era’s educational computing boom. It was published in the seminal People’s Computer Company Newsletter in 1973 and later in the anthology What to Do After You Hit Return (1975). Its spread was academic and textual—a problem set, a puzzle, a way to teach factors, strategy, and optimal play through BASIC code. For decades, it existed in textbooks, on mainframes, and in the minds of math educators, known by many names: The Factor Game, Factor Blast, Dr. Factor.

The direct lineage to Number Shark passes through Germany. Around 2000, educator Lothar Carl created Der Zahlenhai (“The Number Shark”), an adaptation of the Taxman rules tailored for school use, hosted on the NRW educational server. Carl’s version likely added a visual, accessible shell-picking interface and a compelling theme—the cold, calculating shark as the opponent. The game’s rules were now framed not as a dry tax collection but as a predatory extraction.

Number Shark itself was not a commercial product but an apprenticeship project within the CrypTool project. CrypTool is an open-source, freeware suite designed to educate users about cryptography and cryptanalysis. Its context is crucial: a tool for serious learning, not entertainment. The inclusion of Number Shark was likely a nod to the logical, factor-based thinking relevant to cryptographic algorithms (like integer factorization itself). Developed as “work of an apprentice,” it carries the aesthetic and functional hallmarks of a useful utility rather than a polished game. Its release in August 2006 placed it in the twilight of the pre-Steam, browser-based educational software era, where such niche tools lived in the downloadable freeware sections of sites like MobyGames. The technological constraints were minimal—a simple Windows application with text-based or simple graphical presentation, focusing on algorithmic correctness over visual flair.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Antagonism of Factors

Number Shark possesses no traditional narrative. There is no story, no character arcs, no dialogue. Its “theme” is embedded entirely in its mechanics and its title. The player is a human contestant; the opponent is the “Number Shark,” an entity of pure, ruthless logic.

The Core Thematic Conflict: Optimal Scarcity vs. Predatory Logic.

The game board is a set of numbered shells (1 to N). This is a closed system of finite value. The player’s goal is to maximize their score. The shark’s goal, by its deterministic rules, is to maximize its score—which inherently means minimizing the player’s. The theme is one of asymmetric predation. The player selects a number freely (with one key restriction: primes and numbers whose factors are gone become illegal moves). Upon selection, the shark doesn’t just take one rebuttal number; it seizes all remaining proper factors of that number in one systemic gulp. The player is thus forced to think in cascades: “If I take 24, the shark will immediately claim 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12 if they are still there. Is that acceptable? What value am I really netting?”

The shark is not a character with motivation; it is a force of mathematical consequence. Its “intelligence” is the backtracking algorithm provided by Jens Liebehenschel of metio GmbH (as credited on MobyGames). This suggests the developers implemented a solver to ensure optimal play, making the shark a perfect, merciless opponent. The tension arises from the player’s attempt to out-calculate this perfect logic within the game’s escalating constraints. The narrative is written in the player’s mind: the dread of seeing high-value numbers with many low-value factors still on the board, the satisfaction of snagging a large prime or a number whose factors the shark has already consumed, and the inevitable, math-driven capture of the board’s remainder when no legal moves remain.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegant Trap

The gameplay loop is brutally simple yet profoundly deep.

1. Core Loop & Rules:

* Setup: The player chooses N, the maximum number (e.g., 20, 50, 100). Shells numbered 1 through N are present.

* Player Turn: Select any remaining shell x. Add x to player score. Critical Rule: The player may only select a number that has at least one proper factor (a divisor other than 1 and itself) still present on the board. This is the game’s central strategic choke point.

* Shark Turn: The shark automatically claims all remaining shells whose numbers are proper factors of x, adding their sum to its score. If x had no remaining proper factors (meaning it was a “safe” prime or composite with all factors gone), the shark instead claims x itself, denying the player the points.

* Termination: When no legal moves remain (all numbers are either taken or are primes/composites with all factors gone), the shark claims all remaining shells. The player wins if their total > shark’s total.

2. Strategic Deconstruction:

The game is a masterclass in negative space strategy. High-value numbers (e.g., 100) are often traps because they have many small-factor followers (2, 4, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50). Taking 100 might net 100 points but gift the shark a large haul. Low-value primes (2, 3, 5, 7, 11…) are often “safe” picks late-game because the shark can take them, but they have no factors to steal from you. The optimal strategy involves carefully pruning the factor tree to leave the shark with inefficient, low-value collections while you hoard high-value, “factor-isolated” numbers.

The backtracking algorithm mentioned in the credits is the unsung hero. It implies the developers understood the game’s computational complexity and likely used it to verify optimal human strategies or perhaps even provide a hint system (though not documented). This elevates the game from a casual puzzle to a serious mathematical toy.

3. Interface & Presentation:

As a MobyGames entry notes, its perspective is “Text-based / Spreadsheet” with “Menu structures.” This is not a bug but a feature. The interface is functional, displaying the numbered list of available shells, scores, and perhaps a simple prompt. There is no fluff. The UI serves the pure cognitive load of factor calculation. This austerity reinforces the theme: you are in a sterile, logical arena.

4. Innovative/Flawed Systems:

* Innovation: Its primary innovation is the brilliant, cruel asymmetry. The single-player “Taxman” variant, where the human is always the “taxpayer,” creates a unique pressure. You are always on the offensive, but every offensive move triggers a defensive (but automated) counter-strike from the system. The rule that you cannot pick a number without remaining factors is the genius constraint that prevents trivial “prime-grabbing” endgames.

* Flaw: The game has no native “undo.” A single misclick, a miscalculated factor assumption, can doom an entire session. For an educational tool, a “take back” or “simulate shark response” preview would be invaluable for learning. Its minimalist design offers no tutorial beyond the rules text.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Abacus

Number Shark exists in a world of pure number. There is no “world” in a traditional sense—no levels, no environments. The “setting” is the abstract plane of the integer set 1..N. The “atmosphere” is one of cold, logical pressure.

Visual Direction: Given its source as a CrypTool bundle and its MobyGames classification, its graphics are almost certainly basic Windows GDI elements: numbered buttons or list items, a score display, perhaps a simple shark icon. It is functionally identical to how one might implement the game in a spreadsheet. This is its strength. Any attempt at elaborate oceanic theming—actual sharks, swimming animations, coral reefs—would dilute the mathematical purity. The “shark” is a metaphor; keeping it textual preserves the mind’s focus on factors and sums.

Sound Design: It is likely silent or features minimal, possibly irritating, MIDI “event” sounds for picking numbers and scoring. Sound is irrelevant to the core experience. The only “sound” that matters is the mental calculation in the player’s head.

These elements contribute by removing all sensory distraction. The experience is purely internal. The beauty is in the nascent patterns of numbers crossing off a list.

Reception & Legacy: The Unsung Sequence

Contemporary Reception: Number Shark has virtually no recorded reception. On MobyGames, it has 1 player rating (3.5/5) and zero critic or player reviews. It existed in the periphery of the educational software ecosystem—a bundled extra in a niche crypto program. It was not sold, not marketed, not reviewed in PC Gamer or Computer Gaming World. Its audience was whoever downloaded CrypTool and clicked the curious “Number Shark” icon.

Academic & Conceptual Legacy: Its true legacy is inherited from its ancestor, Taxman. The Taxman game is a celebrated fixture in mathematics education research. The sequence of optimal player scores for board size N is OEIS A019312, the “Taxman sequence,” calculated out to N=1000 by enthusiasts. The game has been analyzed in journals like The Arithmetic Teacher, Mathematics Teacher, and SIGCSE Bulletin for its properties as a “good” mathematical game: it has a clear rule set, allows for conjecture and strategy, and embodies deep concepts (factors, multiples, optimal choice under constraint). Number Shark is one implementation—a specific, German-flavored branch—of this robust mathematical tree.

Influence on the Industry: As a standalone .exe, its direct influence is negligible. However, it is a data point in the long history of “minigame as mathematical concept” software. It shares DNA with other pure logic puzzles like Minesweeper or Sudoku in its elegance, though with a more aggressive, zero-sum dynamic. Its bundling with CrypTool is fascinatingly prescient of the modern “game within a game” or “Easter egg” concept, but in a utility, not a AAA title. Its existence proves that even in a cryptographic training tool, a perfectly balanced abstract game has value.

The confusion with the commercial, UK-based Numbershark (by White Space Ltd.)—a completely different, graphics-rich numeracy program for children with dyscalculia—is a notable footnote in naming history. This Number Shark is its austere, logical, European cousin.

Conclusion: A Perfect, Forgotten Seed

Number Shark (2006) is not a game you play for fun in a conventional sense. It is a mathematical instrument. It is a flawless translation of the Taxman problem into an interactive, adversarial format. Its brilliance lies in its ruthless simplicity: a list of numbers, a single rule of factor-based predation, and a stark win condition. It demands calculation, foresight, and acceptance of loss when the logic overwhelms.

Its place in video game history is not on a pedestal but in a case in a museum of game design, labeled “The Essence of a Mechanic.” It demonstrates that compelling gameplay can emerge from a single, elegant mathematical rule without narrative, without progression systems, without flashy graphics. It is a pure strategy puzzle, a duel against a perfect algorithmic opponent. While it languishes with near-zero visibility, its ancestral concept—the Taxman game—thrives in mathematics classrooms and online puzzle forums. Number Shark itself is a successful, if obscure, crystallization of that idea: a perfect, self-contained, and brutally smart game that asks only one thing of the player—to think—and rewards that thinking with the profound satisfaction of beating the shark at its own logical game. For the patient and mathematically inclined, it remains a hidden gem of 2006, a testament to the power of a well-defined rule set.

Final Verdict: ★★★★☆ (4/5) – A masterpiece of minimalist design and mathematical game theory, tragically buried in the documentation of a cryptographic tool. Its obscurity is its only flaw.