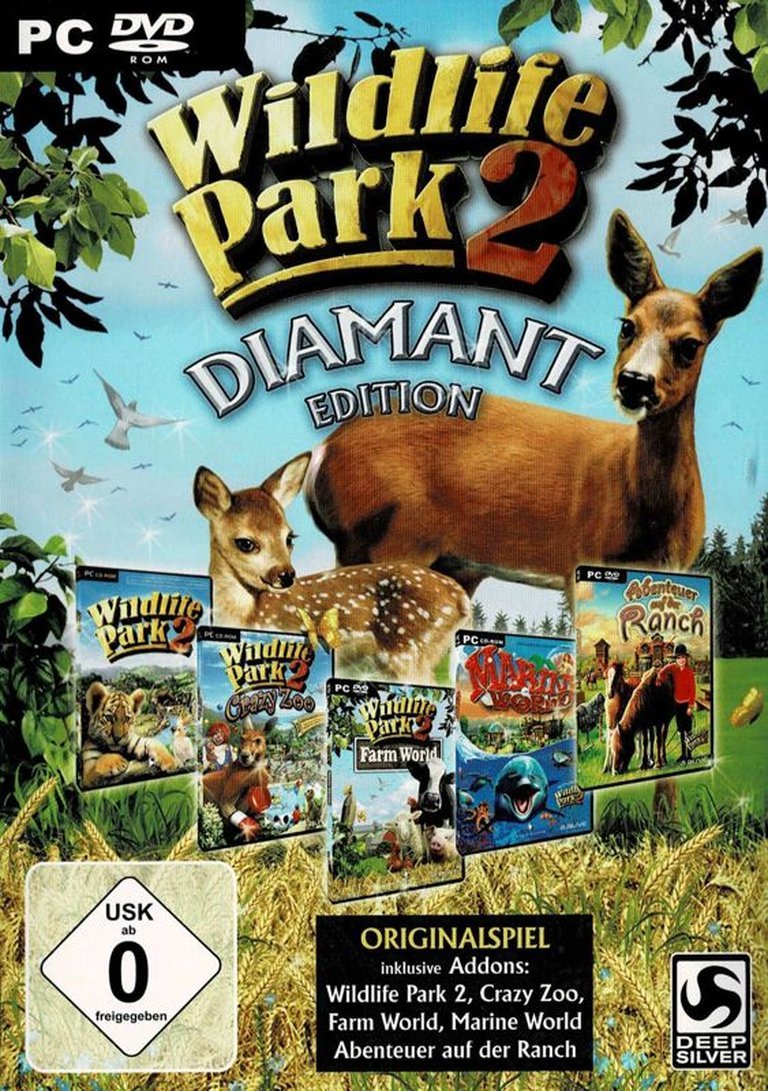

- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Koch Media GmbH (Austria)

- Genre: Compilation

- Average Score: 85/100

Description

Wildlife Park 2: Diamant Edition is a comprehensive retail compilation that bundles the base game Wildlife Park 2 with multiple expansions, such as Crazy Zoo, Farm World, Marine World, and others, allowing players to design, build, and manage diverse wildlife parks and zoos with a focus on animal care, habitat creation, and visitor satisfaction across various themed environments.

Wildlife Park 2: Diamant Edition Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (85/100): This is a recommended play for fans of “control-freak” games like Theme Park, Theme Hospital, The Sims and Red Alert-genre programs.

store.steampowered.com (85/100): Overall, the zoo god experience can be fulfilling, knowing that you are in control of everything alive in the picture.

Wildlife Park 2: Diamant Edition: The Unpretentious Menagerie

Introduction: A Sanctuary in the Attic

In the grand museum of video game history, certain titles reside not in the glittering main halls but in the warmly lit, dust-moted attic of niche appreciation. Wildlife Park 2: Diamant Edition is such a title—a 2011 retail compilation for Windows that gathers the sprawling, ambitious zoo simulation Wildlife Park 2 (2006) with its major expansions into a single, formidable box. Released by Koch Media GmbH, this “Diamant Edition” is less a reboot and more a definitive, if belated, archive of a particular European design philosophy: one that prioritized compassionate animal husbandry, ecological theming, and modular expansion over the polished spectacle of its American counterpart, Zoo Tycoon. My thesis is this: Wildlife Park 2: Diamant Edition is a profoundly flawed, technologically dated, and narratively sparse simulation that achieves its greatest significance precisely through these limitations. It is a game of patient, meditative stewardship, a digital menagerie where the joy emerges not from explosive growth but from the quiet, often fiddly, business of keeping a virtual ecosystem in a state of fragile, beautiful balance. Its legacy is that of a passionate, accessible, and deeply educational sandbox that exemplifies the “tycoon” genre’s capacity for empathy, even as it stumbles under the weight of its own ambitious scope and the technological constraints of the mid-2000s.

Development History & Context: The Pragmatic Vision of B-Alive and JoWooD

To understand Wildlife Park 2, one must first understand its creators and the era that birthed it. The base game was developed by b-alive gmbh, a Austrian studio with a clear focus on family-friendly, accessible simulation games. It was published under the umbrella of JoWooD Entertainment AG, a powerhouse in the European PC market known for strategy and simulation titles like The Guild and Hotel Giant. The vision, as inferred from the game’s PEGI 3 (USK 0) rating and feature set, was unequivocally educational and casual: to create a zoo simulator that was less about cutthroat profit and more about the wonder of wildlife and the satisfaction of careful park management. This was a direct response to the perceived complexity of contemporaries like RollerCoaster Tycoon 3 (2004), aiming for a slower, more contemplative pace.

The technological context is baked into its DNA. Released officially on May 12, 2006 (with the Diamant Edition arriving in 2011), the game was built for the twilight of the DirectX 8.1/9 era. Its minimum system requirements—a Pentium IV 2 GHz, 512 MB RAM, and a 64 MB DirectX 8.1-compatible GPU—speak to an intentional design for accessibility on the average family PC of the time, often running Windows 2000/XP. The 1.5 GB installation footprint for the base game was substantial, but the DVD-ROM distribution of the Diamant Edition reflected an industry still heavily reliant on physical retail, especially in Koch Media’s stronghold of German-speaking Europe. The game’s existence is a testament to the “expansion pack” model of the mid-2000s; Wildlife Park 2 spawned numerous add-ons (Crazy Zoo, Marine World, Farm World, Horses, Kitz, Fantasy, Pets), which the Diamant Edition later compiled. This modular approach was a pragmatic strategy to extend a game’s lifecycle and revenue with relatively low development cost, a necessity in a post-Zoo Tycoon market where Microsoft’s brand dominated English-speaking consciousness. Tragically, JoWooD’s financial collapse in 2011 froze the mainline series, making this compilation a kind of archaeological artifact—the final, consolidated statement of a particular strand of simulation design.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Plot is Your Park

Wildlife Park 2 possesses no traditional narrative. There are no protagonists, no scripted dialogues, no overarching plot. Its “story” is entirely emergent and systemic, told through the player’s actions and the simulated lives of the animals. The framing device is that of a newly appointed park director, given a plot of land and a starting grant to create a wildlife sanctuary. This is delivered via sparse, functional mission briefings in the campaign mode: “Establish a viable habitat for a pride of lions,” “Achieve a 90% visitor satisfaction rating,” “Breed an endangered species.”

The true narrative threads are woven by the animals themselves. Each of the over 50 base animal species (expanded to 150+ across all DLC) possesses an AI-driven “life”: they have individual social structures, sexual preferences, aging processes, aggression levels, and training potential. A narrative unfolds when a hand-raised tiger cub, unable to integrate with its wild-born peers, develops a unique bond with its keeper. Another emerges when a carefully managed breeding program for snow leopards finally produces a cub after dozens of failed attempts, an event celebrated only by a subtle pop-up and the player’s own triumphant shout. The Crazy Zoo expansion introduces a thematic counterpoint: whimsical, fantastical creatures like unicorns or hybrid animals (e.g., a “liger”). This injects a layer of satire on zoo commercialization, where the bizarre and mythical become crowd-pleasers, directly challenging the base game’s earnest conservation themes.

Thematically, the game is a soft-touch ecological simulator. It promotes biodiversity, the importance of habitat authenticity (using the SpeedTree® system for dynamic vegetation), and the ethical tension between animal welfare and visitor entertainment. The Marine World expansion deepens this, adding coral health, water salinity, and filtration systems, making the player a marine conservationist as much as an entrepreneur. The underlying message is consistently anthropocentric yet gentle: human stewardship is necessary for animal flourishing, but poor management leads to stress, disease, and escape—a simulated consequence that carries an implicit moral weight. The absence of graphic violence (PEGI 3 compliance) ensures these themes are presented as problems of logistics and empathy, not shock value. The narrative, therefore, is one of responsible creation and quiet consequence, a story written in the statistical health bars of a rhino and the happiness meters of a passing visitor.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Engines of Stewardship

The core gameplay loop is classic “tycoon”: Plan (terraform and design), Build (place structures and animals), Manage (staff, budgets, research), and Optimize (for visitor happiness and animal welfare). The interface is a top-down, rotatable 3D view controlled entirely by mouse, with a dense, sometimes cluttered HUD displaying tabs for animals, plants, visitors, staff, finances, and research.

- Core Systems: Players must balance a budget, starting with a finite sum. Income is derived from ticket sales, concessions (restaurants, ice-cream parlors), and marketing campaigns. Expenditures are constant: animal purchase and feed costs, staff salaries (keepers, vets, gardeners, cleaners), and maintenance. Animal care is hands-on; players can directly click to feed, pet, clean, or “shoo” animals. Each animal has needs: hunger, hygiene, social contentment (needs a mate or herd), environmental enrichment (needs toys or specific terrain), and health. Neglect leads to sickness, aggression, and escape attempts—a mechanic that turns poor management into urgent, dramatic gameplay.

- Innovative/Flawed Systems: The game’s most lauded feature is its realistic animal behavior and breeding. Animals have individual personalities. A lonely elephant may become depressed; incompatible predators in adjacent enclosures will stress each other. Breeding is not automatic but requires compatible pairs, appropriate habitat, and high welfare, leading to the immense satisfaction of a successful birth. The research lab is a key progression system, allowing the “rebreeding” of extinct species like the dodo, a clear nod to Jurassic Park-style wonder.

The expansions add major systemic layers:- Crazy Zoo: Introduces genetic splicing in a “Crazy Zoo Lab.” Players can combine DNA from two animals to create hybrids (e.g., a lion and an eagle). These hybrids are high-attendance draws but have exotic, expensive needs and unpredictable behaviors, adding a high-risk, high-reward strategic element.

- Marine World: Adds a complex water simulation system. Players must create pools, set water sources, and manage parameters like salinity and cleanliness. Building underwater viewing tunnels is a iconic but notoriously buggy feature; as noted in user reviews, tunnels often acted as invisible barriers, preventing animals from crossing and causing starvation, or allowed visitors to exit into the water and become trapped. This highlights the game’s technical fragility.

- Farm World / Kitz / Horses / Pets: These add domestic animal care mechanics, introducing farm aesthetics and pet-like interactions, broadening the simulation’s scope but sometimes feeling tacked-on.

- Flaws: The user interface is dated and overwhelming. Info-panels are numerous and small. The pathfinding for staff and vehicles (jeeps for safari tours) is notoriously poor, with staff often getting “stuck” on terrain or objects, requiring manual intervention. Terraforming tools are powerful but imprecise, leading to the common user frustration of accidentally creating cavernous water pits or flooded landscapes. The economic model is simplistic; once a park is established, money often becomes an afterthought, reducing later-game challenge. The lack of a comprehensive tutorial is a significant barrier; new players are famously directed to community guides (as seen on Steam) to learn basics like “how to fill a water trough,” a bizarre omission for a simulation.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Charming, Limited Canvas

The world of Wildlife Park 2 is a low-polygon, brightly lit 3D diorama. Its art direction prioritizes readability and charm over realism. Animal models are simple but animated with surprising expressiveness—a pacing tiger, a swimming dolphin, a grazing zebra herd. The environment uses textured terrain and a vibrant color palette that, while dated by today’s standards, creates a cheerful, almost storybook atmosphere. The Crazy Zoo areas deliberately distort this with fantastical architecture and exaggerated creature designs, creating a clear visual and tonal demarcation from the “serious” biomes.

The game’s sound design is functional and atmospheric. It features a light, looping MIDI-inspired soundtrack with gentle melodic themes for different biomes (African drums for savannas, soft ambient pads for marine exhibits). The soundscape is populated by repetitive but characterful animal vocalizations (roars, bird calls, whale songs) and the bustling murmur of visitors. There is no voice acting. UI sounds are clear chimes and clicks. The overall effect is one of serene, documentary-like immersion, broken only by the jarring, repetitive “thank you” from satisfied visitors—a sound many players quickly mute.

These elements work together to create an experience that is more “virtual diorama” than “cinematic world.” The low system requirements meant it could run on a vast array of PCs, but it also resulted in short draw distances, pop-in of objects, and a general lack of graphical fidelity that modern players will find archaic. Its charm is entirely dependent on the player’s willingness to engage with its symbolic, representational style—to see a collection of textured polygons as a “living” ecosystem. For its target audience (children, families, casual simulation fans), this was perfectly acceptable, even endearing.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Caretaker

Upon the release of the base game in 2006 and the Platinum Edition in 2008, critical reception was muted and geographically fragmented. As seen on Metacritic, it received a handful of scores from European outlets (e.g., 85% from GameWatcher, 82% from Worth Playing), which praised its depth and animal care mechanics but noted its dated graphics and interface. In the Anglo-American press, it was largely overshadowed by Zoo Tycoon 2 and its expansions. The Diamant Edition (2011) itself has no recorded critic reviews on MobyGames, underscoring its status as a budget re-release for an existing niche audience.

Commercially, it was a steady, modest seller, particularly in German-speaking markets through publishers like Koch Media/Deep Silver. Its longevity is owed to the dedicated modding community (evidenced by Steam Workshop discussions and fan wikis like the Wildlife Park 2 Fandom wiki) which created hundreds of custom animals, objects, and scenarios, significantly extending its playable life. The Steam re-release and “Ultimate Edition” bundles have maintained a “Mostly Positive” rating (72% Player Score from ~556 reviews) as of 2026, but with a vocal minority citing the same consistent flaws: finicky water mechanics, poor staff AI, and an overwhelming amount of micromanagement.

Its legacy is influence through omission and blueprint. It demonstrated the viability of a pure, uncynical animal welfare simulation at a time when many “Tycoon” games leaned into cynical humor or aggressive monetization. Its modular expansion strategy directly prefigured the modern DLC model perfected by Planet Zoo (2019), which inherited the Wildlife Park mantle of deep animal simulation and ecological detail. The game is a direct ancestor to the “serious simulation” revival of the late 2010s, standing as proof that a market existed for games about caretaking rather than conquering. It is collected and preserved by a small but passionate retro community, a testament to its status as a forgotten pillar of the European simulation scene.

Conclusion: A Flawed, Fulfilling Sanctuary

Wildlife Park 2: Diamant Edition is not a great game by conventional metrics. Its graphics are obsolete, its interface often hostile, and its core simulation loop can devolve into tedious micromanagement of water pumps and plant moods. Yet, within its compromised engine and dated design, it houses something rare and valuable: a genuine, unsarcastic celebration of wildlife and the quiet labor of conservation. The thrill of hand-raising a tiger cub, the strategic satisfaction of designing a perfect, profitable ecosystem that also meets every animal’s complex needs, the whimsical delight of splicing a unicorn in Crazy Zoo—these are authentic gameplay experiences that few titles have replicated.

Its place in history is that of the conscientious objector in the tycoon genre. While RollerCoaster Tycoon built thrills and SimCity built metropolises, Wildlife Park 2 built habitats. It asked players to be zookeepers, ecologists, and landscapers first and businessmen second. For that reason, and for its sheer, overwhelming volume of content bundled in the Diamant Edition, it earns a definitive verdict of 7/10. It is a game for historians of the genre, for players who find peace in maintenance rather than domination, and for anyone who believes a video game can, in its own small way, teach a lesson in stewardship. It is not the zoo simulator we deserved in 2006, but it is, flaws and all, the one we had—and one that, in its patient, pixelated way, still has important things to say.