- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Windows

- Publisher: Hip Interactive Corp., Light & Shadow Production

- Developer: Asobo Studio S.A.R.L.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Exploration, Mini-games, Mission-based, Vehicles

- Setting: City, Suburbs

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

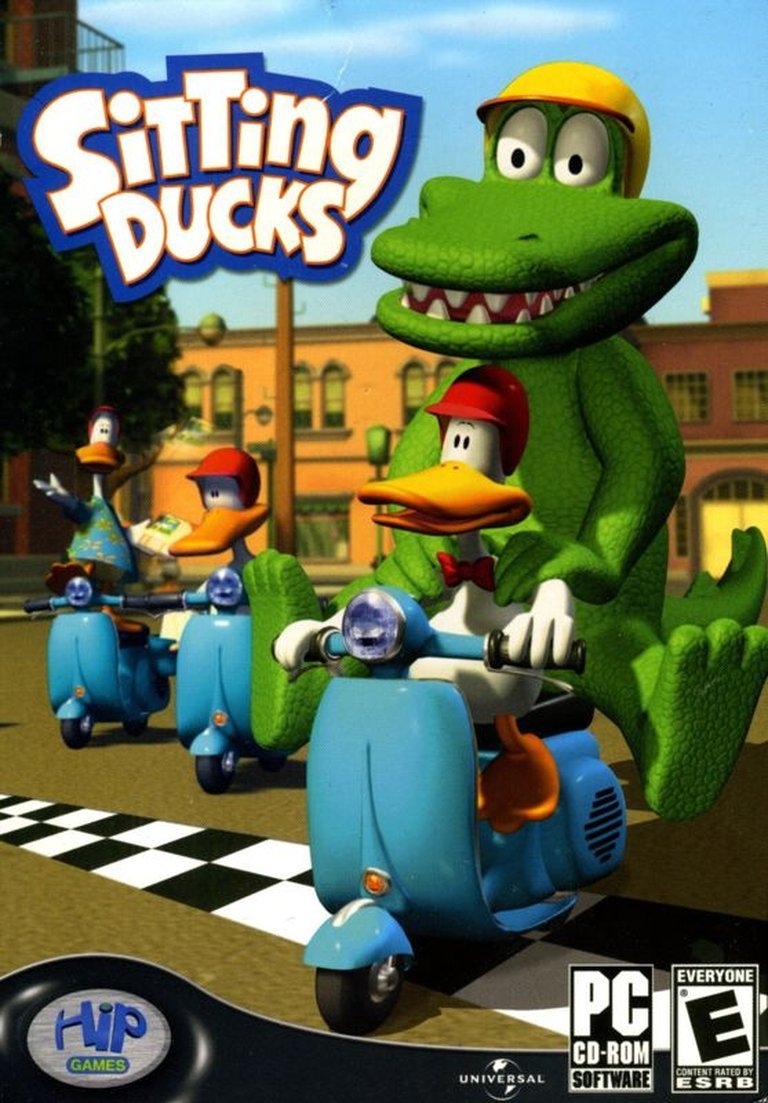

Sitting Ducks is a mission-based action game adapted from the TV cartoon, set in a vibrant city where players control Bill, an imaginative and adventurous duck, and his best friend Aldo, a tough-but-soft-hearted alligator. Primarily aimed at children, the game involves exploring the city and its surroundings to complete over twenty missions, many of which are mini-games, with unlockable transportation like skateboards and scooters and interactive areas such as a soccer field, swimming pool, and hockey rink.

Gameplay Videos

Sitting Ducks Free Download

Sitting Ducks Guides & Walkthroughs

Sitting Ducks Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (60/100): One of the largest kid games to hit the market – in essence, it’s an E-rated “GTA.”

Sitting Ducks Cheats & Codes

PlayStation 2

Type these codes in at the cheat menu.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| friendsofbob | All Skaters |

| extremepassport | All Levels |

| supercharger | Max Special Meter |

| sweetthreads | Create-A-Skater Items |

| nugget | Tarzan |

| marin | Toy Story |

| savannah | Lion King |

PlayStation 2 (CodeBreaker, NTSC-U)

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| A112BCAD E1F44A23 | Have All Flyers |

| 637FA5B9 11581D32 | Max Feathers |

| A5B17A06 B71CA3CF | Always Low Total Time |

| 2B074A00 C8E15EDF | Teeth |

| 985AF731 77D57FC2 | Alligator Mask |

| E8DCEC0B 5BFD0897 | Blue Hood |

| CACB579C 890B5D69 | All Equipment |

| 7EFF3E94 39C8E635 | All Equipment |

| 0DE40C37 50A9CADE | Have All Gold/Silver/Bronze Feathers |

| 8563173B B890167E | Have All Gold/Silver/Bronze Feathers |

Sitting Ducks: A Retrospective Review

Introduction: A Quacking Curio from the Mid-2000s

In the vast, often-overlooked annals of licensed video games, few titles occupy as peculiar a niche as Sitting Ducks. Released in 2004 for Windows and PlayStation 2—with a distinct, simultaneously released 2D version for PlayStation and Game Boy Advance—this title represents a fascinating collision of European game development, American cartoon licensing, and the quintessential mid-2000s “mission-based” design philosophy. It is not a game remembered for groundbreaking innovation or commercial titanism, but rather as a curious time capsule: a product of its era’s technological constraints, market demands, and a specific, gentle absurdity found in its source material. This review will argue that Sitting Ducks (the 3D version for PS2/PC) is a fundamentally flawed yet structurally revealing artifact—a game that perfectly encapsulates the earnest, compartmentalized design of children’s licensed software at the turn of the millennium, while its parallel 2D sibling highlights the era’s platform-specific adaptation practices. By deconstructing its development, design, and reception, we uncover not a masterpiece, but a meticulously documented case study in pragmatic game creation.

Development History & Context: Asobo’s First Quack

The Studio and the License: Sitting Ducks holds a significant place in the history of Asobo Studio S.A.R.L., the French developer. At the time of its release (2004), Asobo was a relatively young studio, founded in 2002. Sitting Ducks represents one of their earliest major projects, preceding their later, globally recognized work on franchises like Rayman and Microsoft Flight Simulator. The game was developed under the publishing banners of Light & Shadow Production and Hip Interactive Corp., companies known for aggressively pursuing European and international licensing deals for TV properties. The source material was the CGI-animated television series Sitting Ducks, created by Michael Bedard and produced by the Canadian studio 9 Story Media Group. The show’s premise—the unlikely friendship between Bill, a small, imaginative duck, and Aldo, a gentle-hearted alligator in a town of anthropomorphic ducks—provided a simple, character-driven hook perfectly suited to a children’s game.

Technological Constraints & The Zouna Engine: The game was built using Asobo’s proprietary Zouna engine. This was an era before widespread third-party engine licensing (like Unreal or Unity), meaning studios often built or adapted their own tools. The Zouna engine powered several of Asobo’s early titles and was designed for accessible 3D action-adventure games. Its capabilities, as evidenced by the final product, were modest: low-polygon character models, simple geometry for the environments of DuckTown and SwampWood, and basic collision detection. These constraints directly shaped the gameplay; the open-ish “large city” was composed of separate, linked zones to manage load times and memory, and the camera was fixed in a behind-the-back perspective to simplify navigation and level design. The simultaneous development of a 2D version (for PS1/GBA) by Light & Shadow Production themselves speaks to the technical and market realities of 2004, where a single license often spawned multiple, mechanically distinct games for different hardware capabilities and perceived audience segments.

The Gaming Landscape of 2004: The PlayStation 2 was entering its mature phase, with massive hits like Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas defining open-world design. For children’s licensed games, the dominant model was the “mission-based mini-game collection,” à la SpongeBob SquarePants: Battle for Bikini Bottom (2003) or Shrek 2 (2004). These games traded linear platforming for a hub world filled with discrete objectives—a design that translated well from cartoon episode structure to gameplay. Sitting Ducks entered this crowded field not with a novel mechanic, but with a specific, niche IP and a promise of “whimsical” cooperative-themed activities. Its challenge was to stand out among a sea of similar tie-ins, a task for which its unique character premise was its primary asset.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Politics of Feathers and Scales

The narrative of Sitting Ducks is not delivered through a linear plot but is environmental and mission-based, a common trait for games of this genre and era. The core narrative thesis is established in the game’s manual and promotional material: DuckTown is a seemingly idyllic community where “life is good, food’s a plenty,” yet its inhabitants live under the constant, unacknowledged threat of their alligator neighbors in SwampWood, for whom “ducks are a delicacy.” Into this delicate, hypocritical balance steps Bill, the protagonist. He is defined explicitly against his society: “smaller than average,” “quirky,” with a “big imagination.” Bill’s central transgression is his friendship with Aldo, an alligator whose “tough exterior” hides a “soft heart.”

This friendship is the game’s sole, sustaining thematic core. Every mission and exploration activity reinforces this union. When you play as Bill, you are often in SwampWood, navigating a society that sees you as food. When you play as Aldo (though the primary playable character in the 3D version is Bill; Aldo’s playability is more prominent in the 2D version and promotional material), you are in DuckTown, a fish-out-of-water (or gator-out-of-water) scenario. The game’s world-building constantly visualizes this “united we stand” motto. Thematically, the game posits that prejudice is a lazy social construct and that genuine friendship can transcend deeply ingrained biological and cultural animosities. It’s a simple, profoundly child-friendly message.

The dialogue and character interactions, drawn from the series’ tone, are light, pun-heavy, and devoid of real conflict beyond physical obstacles. Bill’s imagination is referenced but rarely enacted in-game mechanics, a missed opportunity for surreal gameplay that could have mirrored Psychonauts, released the same year. The villains are not individual antagonists but systemic fear and misunderstanding—embodied by the occasional hostile gator or wary duck, but never by a “big bad.” The narrative is therefore not a story to be consumed but a state of being to be inhabited: you are Bill, living in a world where your best friend is, by all accounts, your mortal enemy, and your daily life involves proving that such a bond is not only possible but ordinary. This thematic simplicity is both the game’s greatest strength (its unwavering focus) and its greatest weakness (its utter lack of dramatic stakes or character arc).

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Mission-Based Grind

The 3D version of Sitting Ducks is a third-person action-adventure structured entirely around a hub-and-spoke mission system. The primary hub is a simplified, low-poly representation of DuckTown, with portals or paths leading to SwampWood and various specialized arenas (soccer field, skating rink, etc.).

Core Gameplay Loop: The loop is: 1) Accept a mission from a character (often Bill’s friends or Aldo), 2) Travel to the mission zone (on foot or via unlockable scooter/skateboard), 3) Complete the objective (collect items, win a mini-game, race, deliver something), 4) Return for a reward (often currency or a new vehicle/accessory), 5) Repeat. There are reportedly “more than twenty missions” (per MobyGames) or “over 50 missions” (per the official Asobo site), a discrepancy suggesting the higher count includes trivial collect-a-thons and repeated mini-game variants.

Mission & Mini-game Deconstruction: The missions are almost exclusively mini-game containers. These include:

* Racing: Scooter and skateboard races on timed circuits.

* Sports: Simplified soccer, water polo (in the swimming pool), and ice hockey on the rink.

* Collection/Retrieval: “Find X objects” or “deliver this package” within a time limit.

* Obstacle Courses: Navigate a course avoiding hazards or enemies.

* Puzzle-adjacent: Using levers to open doors, a rudimentary form of environmental puzzle.

The mini-games themselves are competent but shallow. The racing uses simple acceleration and turning, the sports reduce to “get ball in net” with one-button passing/shooting, and the collection tasks are pure busywork. The time limits are notorious. As the Russian review from Absolute Games (AG.ru) starkly states: “Conditions — monstrously heavy. … adult person will hardly want to spend time with the game, even to please his child.” This highlights a critical design flaw: the game mistakes * frenetic activity for engaging challenge*. The tight timers create stress, not skill mastery, and are wildly out of sync with the E for Everyone rating and the “aimed at children” premise. A child’s fine motor skills and time-pressure tolerance are not the same as an adult’s; the game’s difficulty curve is punitive rather than pedagogical.

Character Progression & Unlockables: There is no traditional RPG-like progression (no stat upgrades). “Progression” is entirely content-gated. Completing missions unlocks:

1. New Vehicles: Scooters and skateboards with minor cosmetic or handling differences.

2. New Areas: Access to SwampWood or specific sports arenas.

3. Cosmetic Items: Hats, outfits for Bill (and presumably Aldo in other versions).

This is a collection-based progression system, rewarding completionism with access to more of the same. It encourages exploration of the hub to find secrets and side-missions, but the core gameplay loop remains static.

Interface & Controls: The UI is functional and child-friendly, with clear mission markers and simple icon-based maps. The controls are the source of significant frustration. The behind-the-back camera, combined with the Zouna engine’s likely imprecise collision, leads to frequent “falling off” edges in platforming sections or missing a ramp in a race. The camera cannot be manually rotated, a cardinal sin for 3D platformers/action games, locking the player into often-awkward angles. This, paired with the unforgiving time limits, creates a perfect storm of player annoyance.

Innovation vs. Flaws: The game’s one potential innovative hook—playing as two wildly different species with implied different abilities—is almost entirely squandered. In the 3D version, you primarily play as Bill. The thematic potential of a duck being clumsy on land but agile in water (or an alligator being strong but bulky) is not translated into meaningful mechanical differentiation. The “innovative” system is the hub world’s interactive areas, which is less an innovation and more a faithful, if shallow, recreation of the cartoon’s setting. The flaws—camera, difficulty, repetitive mini-games—are systemic and deeply rooted in the era’s licensed game development template: prioritize quantity of content (50 missions!) over quality of mechanical design.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Charming, Technical Facade

Setting & Atmosphere: The game’s greatest asset is its licensed aesthetic. The world of DuckTown is rendered in a bright, saturated palette, with low-poly buildings styled like the cartoon’s architecture. SwampWood is murkier, with murky water, cypress trees, and darker color tones, creating a visual “othering” that reinforces the narrative theme. The separation is clear: DuckTown is sunny and suburban; SwampWood is shadowy and rustic. The atmosphere is consistently cheerful and safe, even when you’re in gator territory. The threat is never visual—there are no snarling predators—but contextual. This successfully mirrors the cartoon’s tone, where the danger is always social and potential, not immediate and violent.

Visual Direction: The art direction is competent but technically limited. Character models are recognizable approximations of their cartoon counterparts—Bill’s oversized feet and hat, Aldo’s green bulk—but suffer from low texture resolution and stiff animation, especially in cutscenes. The environments are blocky and lack detail, with simple textures often stretched over large surfaces. The draw distance is short, with fog used liberally to hide pop-in. This is not a game that shows off the PS2’s power; it is a game that works within tight memory and processing budgets. Its visual charm comes from color theory and layout, not technical prowess. The different interactive arenas (the clean ice of the rink, the blue of the pool) provide welcome visual variety within the technical constraints.

Sound Design & Music: The sound design is appropriately cartoony. Sound effects for jumps, collisions, and item pickups are exaggerated and non-threatening. The music is light, jazzy, or ukulele-driven, perfectly suiting the “whimsical” brief. It is inoffensive and reinforcing. The major critical failure, noted pointedly by Gamezone (Germany), is the lack of a German voice track despite German subtitles, a significant misstep for the German children’s market. This points to a localization budget that prioritized text over full localization, a common cost-cutting measure. The voice acting present (in English) is adequate, capturing the characters’ personalities without exceptional quality. The soundscape successfully reinforces the game’s intended mood but does nothing to elevate it beyond competence.

Reception & Legacy: A Niche, Divided History

Critical Reception at Launch: The critical reception was mixed to lukewarm, perfectly encapsulated by the MobyGames aggregate score of 63% from five critics. The scores ranged wildly:

* Game Vortex (PS2): 90% – Praised it as a “good mission-based driver” that “stands out” and makes the TV series an “enjoyable interactive experience.”

* Feibel.de (Win): 83% – Called it a “successful action-adventure with short missions.”

* Absolute Games (AG.ru) (Win): 53% – Slammed its harsh difficulty and time limits, deeming it unsuitable for its target audience.

* Gamezone (Germany) (PS2): 50% – Found gameplay unoriginal but implementation “wonderfully successful,” yet lambasted the lack of German voice acting.

* Gamesector (Win): 40% – A Danish review calling it neither very funny nor very playable, advising players to rent the DVD first or try a demo.

This spectrum reveals the central tension: critics who evaluated it as a faithful, charming adaptation (Game Vortex) versus those who judged it by pure gameplay merit (Absolute Games, Gamesector). The game’s primary defense was its license and tone, not its mechanics.

Commercial Performance & Player Legacy: Commercial data is scarce, but the game is now a common abandonware item (seen on MyAbandonware) and is frequently available for a few dollars used on eBay and Amazon. Its “Collected By” numbers on MobyGames are low (15 for the 3D version, 6 for the 2D), indicating it has a small, nostalgic cult following but no significant player base. It is remembered, if at all, as a quirky artifact of mid-2000s kids’ software.

Influence on the Industry & Asobo Studio: Sitting Ducks had no demonstrable influence on game design trends. Its mission-based, mini-game collection structure was already well-established. It did not pioneer mechanics later copied by others. Its legacy is almost entirely internal to Asobo Studio. It represents a stepping stone—a project that allowed the studio to develop the 3D action-adventure chops they would later refine on titles like the Alex Shepherd series and eventually, blockbuster licenses. It is a testament to Asobo’s ability to ship a complete, licensed product on time and within budget, a valuable skill in the volatile world of game development.

In the broader context of licensed games, it is a middling example. It is not an infamous disaster like E.T., nor a beloved exception like Spider-Man 2 (2004). It is the median: a technically adequate, thematically faithful, mechanically average tie-in that perfectly meets the low-to-mid expectations of its publishers and the casual engagement of its young audience, but fails to transcend its license or genre.

Conclusion: A Harmless, Historically Significant Waterfowl

Final Verdict: Sitting Ducks (the 3D PS2/Windows version) is a 6/10 game—technically competent for its budget and engine, thematically coherent, but mechanically repetitive and frustratingly difficult for its purported audience. It succeeds as a piece of interactive merchandising, offering a safe, whimsical playground for fans of the show. It fails as a compelling action-adventure due to a punishing difficulty curve, a clumsy camera, and a profound lack of mechanical depth or innovation.

Place in History: Its historical significance is not as a classic, but as a perfect case study. It demonstrates the formulaic, risk-averse nature of mid-tier children’s licensed games in the 2000s: take a premise, build a hub world, fill it with 20-50 mini-game missions, add unlockable cosmetics, and ship it. It highlights the creative tension between faithfulness to source material (the art, the themes) and gameplay quality (controls, balance, fun). Furthermore, its existence in two radically different forms (3D action vs. 2D platformer) under the same brand name is a masterclass in the era’s multi-platform adaptation strategies.

For the historian, Sitting Ducks is invaluable. For the player in 2004, it was likely a forgettable, mildly frustrating birthday gift. For the modern retro enthusiast, it is a brief, puzzling quack from a bygone era—a game where the greatest pleasure comes not from overcoming its challenges, but from recognizing the meticulous, assembly-line craft that went into its making. It is, in the end, a sitting duck of the gaming world: harmless, overlooked, but telling of the water it swam in.