- Release Year: 1980

- Platforms: Intellivision, Windows, Xbox 360

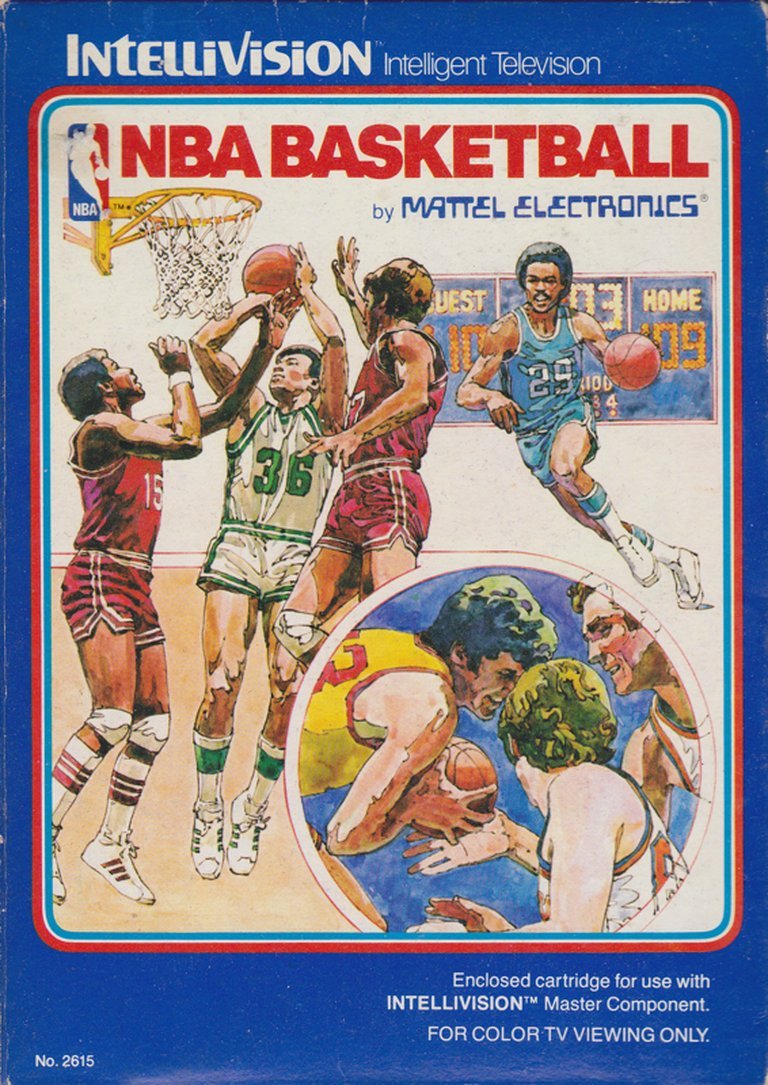

- Publisher: Mattel Electronics, Microsoft Corporation

- Developer: APh Technological Consulting

- Genre: Sports

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat

- Gameplay: Blocking, Dribbling, Jump shots, Passing

- Setting: Basketball court

- Average Score: 71/100

Description

NBA Basketball is an early basketball simulation game released in 1980 for the Intellivision, officially licensed by the NBA but featuring only generic Home (red) and Visitor (green) teams without real names or players. Set from a side-court angle with a basic court layout including center and free-throw lines, it supports two players controlling three-man teams in four timed quarters with a 24-second shot clock, incorporating passing, blocking, and jump shots.

NBA Basketball Reviews & Reception

gamesreviews2010.com (60/100): Basketball is a classic video game that is still enjoyable today.

NBA Basketball (1980): The Genesis of a Virtual Hardwood

Introduction: The First Brick in the Foundation

Long before the dazzling photorealistic arenas of NBA 2K or the arcade explosion of NBA Jam, there was a stark, side-view court on the Intellivision. NBA Basketball (marketed simply as Basketball on its title screen) is not merely a game; it is the foundational artifact of the sports video game genre’s most lucrative franchise. Released in 1980 by Mattel Electronics and programmed solo by Ken Smith, this title holds the immutable distinction of being the first basketball video game officially licensed by the National Basketball Association. Yet, this licensing triumph exists in fascinating, almost contradictory tension with the game’s profound abstraction. It presents the NBA’s seal of authenticity while offering no team names, no player identities—only red versus green. This review will dissect NBA Basketball not as a playable classic by modern standards, but as a critical historical document. It is a testament to the creative problem-solving required in the early days of home console gaming, a blueprint that established core conventions while highlighting the technological and design chasms that would take decades to cross. Its legacy is less in its gameplay and more in its pioneering spirit and the fundamental questions it asked about how to simulate a sport within severe hardware constraints.

Development History & Context: Mattel’s Goliath and the Intellivision’s Ascent

Studio & Vision: The game was developed by Mattel Electronics, the toy manufacturing behemoth that entered the volatile home console market with the Intellivision in 1980. The Intellivision was marketed as a more sophisticated, “intelligent” alternative to Atari’s VCS/2600, with superior sound and graphics capabilities. The vision for NBA Basketball was clearly to leverage this technological edge to create a definitive sports simulation, a goal underscored by securing the coveted NBA license. This was a major marketing coup, positioning Mattel’s offering as the authentic basketball experience for the living room. The entire project was the work of Ken Smith, a programmer within Mattel’s “Blue Sky Rangers” development team. His solo credit speaks to the small-scale, intensely focused nature of early game development, where one individual’s design and coding decisions shaped the entire experience.

Technological Constraints: The Intellivision’s hardware, while advanced for its time, was profoundly limited by 21st-century standards. The game’s diagonal-down perspective and fixed/flip-screen visual style were not aesthetic choices born of artistry, but pragmatic solutions to memory and processing limits. The court is a static, minimalist tableau—a few lines representing the key, free-throw lane, and center line. Player sprites are simple, blocky figures with minimal animation (running, dribbling). The absence of scrolling meant the entire court existed in a single screen, with possession flipping the camera’s focus when the ball crossed half-court. The direct control interface, using the Intellivision’s unique disc-shaped controller with its side-mounted keypad for passing, was an attempt to translate basketball’s spatial and strategic elements onto a 12-button pad. The shot clock and game timer were simulated through internal programming counters, a clever use of the system’s resources.

Gaming Landscape: NBA Basketball debuted into a burgeoning sports game market. It directly competed with Atari’s Basketball (1978 for the 2600), which was a more primitive, abstract one-on-one game. Mattel’s marketing aggressively contrasted the Intellivision’s capabilities against Atari’s, using famous “Intellivision vs. Atari” comparison commercials. In this context, NBA Basketball was a system seller—a flagship title demonstrating the Intellivision’s prowess. However, the broader landscape was one of stark experimentation; there was no established formula for a basketball sim. Games like Basketball (1974 arcade) and Basketball Mania were simple score-attack or half-court affairs. NBA Basketball’s ambition—a full-court, 3-on-3 simulation with quarters and an overtime—was groundbreaking, even if its execution was skeletal.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Ghosts in the Machine

NBA Basketball possesses no traditional narrative. There is no plot, no characters with names or backstories, no dialogue, and no story mode. Yet, its very structure implies a powerful, if minimalist, thematic core. The game is a study in pure, unadorned competition. The absence of franchise names, player likenesses, or even a season mode strips basketball down to its absolute fundamentals: two teams, two baskets, one ball. This creates a thematic vacuum that the player’s imagination fills. The red team and the green team are not the Celtics and the Lakers; they are abstractions, archetypes of “Home” and “Visitor”.

The most profound thematic tension lies in the license vs. the abstraction. The NBA logo on the box and cartridge screams “authenticity,” promising gamers a connection to the professional sport they watched on television. Inside, that promise is immediately broken. You cannot play as Larry Bird or Magic Johnson. You cannot experience the Boston Garden or The Forum. This reveals an early, crucial truth about sports licensing: it was initially a marketing shield and a branding tool, not a guarantee of simulation fidelity. The theme becomes one of symbolic representation. The game asks: what is the minimum required to evoke “basketball”? The answer is a court, a hoop, a ball, and five moving figures (three per side, with two AI). It is a game about systems and spacing, not personalities.

The player’s role is not that of a “coach” or a “GM” but of a direct puppeteer, a single consciousness controlling one avatar within a team of three, with the others acting as autonomous but limited agents. This creates a unique narrative of individual vs. system. Your controlled player is your avatar, but your success is utterly dependent on the AI’s execution of passing and defense—a theme that would plague and inspire sports game designers for decades. The “overtime” period, a single five-minute quarter, injects a dramatic, sudden-death narrative structure unseen in regular play, framing the game’s conclusion as an intense, winner-takes-all climax.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Architecture of Pixels

Core Loop & Structure: The game is a two-player-only, head-to-head contest. The structure mimics a professional game: four quarters, each a simulated twelve minutes governed by a 24-second shot clock. A tied game triggers a single five-minute overtime. This is a surprisingly robust framework for the era.

Control & Player Roles: Each player controls a three-man team. On offense, you directly control the ball-handler. Using the Intellivision’s keypad, you select a teammate’s location (or the basket) to pass. If the pass is caught by a computer-controlled teammate, control seamlessly switches to that player. This passing system was hailed by Video magazine as “superb” for its strategic depth, allowing for quick ball movement and creating open shots. On defense, you control a single “captain.” This is a critical and distinctive design choice. You do not switch between defensive players; you are locked to one, who can block shots, intercept passes, and rebound. The other two defenders are AI-controlled and can steal the ball. This asymmetric control—direct offensive control vs. a single defensive “captain”—creates a fascinating strategic asymmetry.

Shooting & Scoring: Two shot types exist:

1. Jump Shot: Shorter range, less likely to be blocked. Uses the “fire” button.

2. Set Shot: Can be attempted from longer range, but has a higher chance of being blocked.

All baskets, regardless of distance, are worth two points. There are no three-point shots and, most critically, no foul shots or free throws. This eliminates an entire strategic layer of the sport (fouling, Hack-a-Shaq strategies, penalty situations) and reduces the scoring system to a binary success/failure model.

The “Captain” System & AI: The defensive captain system is the game’s most innovative and flawed mechanic. By limiting the player to one defender, the AI teammates must provide help defense and coverage. The AI’s ability to steal the ball is powerful, but its decision-making is rudimentary. Offensively, the AI teammates will receive passes and attempt shots, often with questionable judgment. This creates a gameplay loop where you are both quarterback and point guard on offense, but a lone wolf on defense, hoping your AI cohorts make smart rotations. It’s a system ripe for exploitation and frustration.

The Pass-Reset Shot Clock & Strategic Implications: One of the most bizarre and strategically impactful rules is that the 24-second shot clock resets upon every completed pass. This single design decision warps the entire offensive strategy. Theoretically, as noted in the sources, an offensive team could pass the ball indefinitely between its three players without ever attempting a shot, consuming the entire quarter. While likely an unintended quirk, it highlights the disconnect between simulating a sport and faithfully replicating its rules. It prioritizes ball possession over shot attempts, creating a “keep-away” strategy that is antithetical to basketball’s essence.

Flaws & Limitations: The game is exclusively two-player. There is no solo mode against the CPU; you must have a human opponent. This was standard for the era but limits its accessibility. The uniformity of teams (red vs. green) and the lack of any statistical tracking or player development remove any sense of progression or franchise building. The “full court” is a single-screen flip, which can be disorienting and lacks the sense of transition present in real basketball or later games.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Minimalist Theater

Visual Design & Perspective: The game’s world is defined by its diagonal-down, side-court perspective. This viewpoint was chosen to clearly show the depth of the court (the key area) and the relationship between players on opposite sides. It sacrifices the frontal view of the basket for a better sense of positional play. The court is rendered with geometric simplicity: lines for the boundaries, the center circle, the free-throw lane, and the key. The baskets are simple vertical lines with a horizontal rim. The “floor” is a blank color, typically a court-like wood tone or plain background.

Character & Animation: Players are small, blocky sprites with one frame for running/dribbling and one for shooting. There is no differentiation in height, build, or animation between a “center” and a “guard.” The only visual distinction is team color (red vs. green). The dribbling animation is a simple up-and-down bob of the player and a separate ball sprite. When a shot is released, the ball travels in a high, static arc toward the basket. These animations are functional, conveying the idea of action but not its fluidity or physics.

Atmosphere & Immersion: Immersion is nonexistent in a modern sense. There is no crowd noise, no arena, no announcer, no player names or numbers. The atmosphere is one of pure, sterile competition. The focus is entirely on the tactical movement of the colored blocks on the screen. This starkness forces the player to mentally project the drama of a basketball game onto the pixels. It is a blank canvas where the player’s imagination must paint the crowds, the tension, and the athleticism.

Sound Design: The Intellivision’s sound chip produces simple, beeping tones. The soundtrack consists of:

* A short, rising beep for the tip-off.

* A repetitive, metronomic beep-beep-beep for the shot clock, one of the game’s most iconic and stressful auditory cues.

* A satisfying thud for a made basket.

* A higher-pitched bonk for a missed shot or rim bounce.

* A sharp buzz for a whistle (likely for shot clock violations or end of quarter).

The sound is entirely functional, providing critical auditory feedback for game state (shot clock, scoring) but creating no sense of environment or excitement. It is the sound of pure mechanics.

Reception & Legacy: A Polarizing Pioneer

Contemporary Reception (1980-1983): Critical reaction was mixed, reflecting the nascent state of the genre. Video magazine’s “Arcade Alley” column (August 1980) gave it a positive review, praising its “superb” passing system and concluding it would “have fans cheering”, even while noting the absence of free throws and “free agents” (likely meaning player movement/transactions). This review focused on its successful simulation of core basketball flow. In stark contrast, a retrospective review from The Video Game Critic (2002) dismissed it as “slow and boring,” stating it hadn’t aged well and that the two-player-only requirement made it a chore. This dichotomy—praise for its system vs. condemnation for its pace and simplicity—defines its historical reception.

Commercial Performance & Distribution: As the first NBA-licensed game, it was a significant commercial product for Mattel. Its distribution was dual: sold with the NBA branding on box and cartridge for the Intellivision, and sold by Sears for its private-label “Super Video Arcada” (the Sears version of the Intellivision) without the NBA name or logo. This indicates the license was a powerful retail differentiator but not an absolute requirement for the game’s distribution.

Long-Term Legacy & Influence: NBA Basketball’s legacy is that of a trailblazer with few direct descendants. It established the template of:

1. Licensed sports branding.

2. Full-court, multi-player simulation (3-on-3).

3. Quarters and a game clock.

4. Passing as a primary offensive mechanic.

However, its specific systems—the captain defense, the pass-reset shot clock, the lack of fouls/3-pointers—were not embraced by future developers. Instead, it served as a proof-of-concept. It showed that a console could attempt a complex team sport simulation. Its real influence is in its existence, paving the way for the more polished, ultimately more successful sports titles on the Intellivision itself (like World Series Baseball) and, later, the explosion of sports gaming on 16-bit consoles with NBA Live and NBA 2K. The modern expectation of an NBA-licensed game with full rosters, realistic physics, and single-player modes can be traced back to the bold, if crude, step Mattel took in 1980. Its preservation in compilations like Intellivision Lives! (1998) and Microsoft’s Game Room service is its primary claim to continued relevance, allowing new generations to experience this pixelated genesis.

Conclusion: A Frozen Relic on the Hardwood

NBA Basketball for the Intellivision is a game best understood as an archaeological specimen. To play it today is to engage in a form of digital paleontology, examining the earliest fossilized remains of what would become a titanic genre. Its gameplay is, by any objective modern metric, flawed, slow, and achingly primitive. The mechanics are bizarre, the presentation barren, and the lack of a single-player mode a deal-breaker for most. The “captain” defense system is clever in theory but frustrating in practice, and the shot-clock reset on passes is a game-breaking quirk.

Yet, to judge it solely on its current playability is to miss its monumental significance. In 1980, it was a technical marvel and a marketing landmark. It was the first to bridge the gap between the fandom of professional basketball and the home console, using the NBA’s logo as a seal of approval. Ken Smith’s design, with its focus on passing and spatial team play, demonstrated an understanding of basketball’s strategic heart, even if the execution was clumsy. It asked the fundamental question—”How do you make a basketball game work with three players per side and a limited screen?”—and provided an answer, however imperfect.

Its verdict in the pantheon of video game history is secure: NBA Basketball is not a great game, but it is an essential one. It is the primordial ooze from which the complex ecosystems of sports simulation eventually evolved. It stands as a testament to an era of constraints that bred creativity, and a reminder that every graphical polygon, every motion-captured animation, every licensed player name in today’s NBA 2K traces its lineage back to this quiet, side-view court where red and green blocks chased a bouncing dot. It earns its place not on the basis of fun, but on the unwavering foundation of being first.