- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Alawar Entertainment, Inc.

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Falling block puzzle, Tile matching puzzle

Description

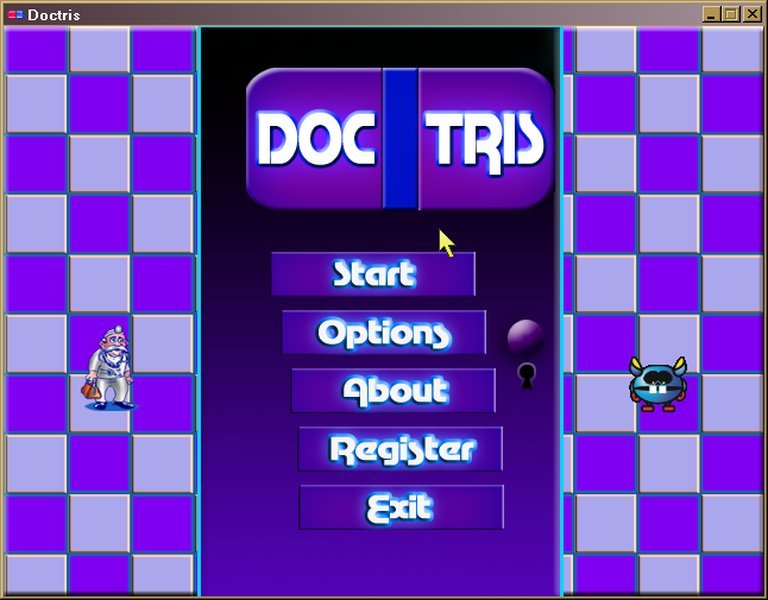

Doctris is a puzzle game set in Doctor Smith’s virus-infested laboratory, where players manipulate falling pills—each with two colored segments (red, blue, or green)—to create matching lines that vanish and destroy the hidden viruses. Inspired by Dr. Mario and featuring Tetris-like mechanics, the goal is to clear all viruses from each vial across three difficulty levels that adjust falling speed and required line length.

Doctris: A Microscopic Masterpiece or a Forgotten Formula? An Exhaustive Retrospective

Introduction: The Petri Dish of Puzzle Gaming

In the vast, bustling ecosystem of video game history, certain titles exist not as towering redwoods but as hardy, specialized fungi—perfectly adapted to a narrow niche, briefly thriving, then fading into the substrate, their existence noted only by dedicated archivists and a handful of players with fond, if fuzzy, memories. Doctris, released in March 2004 for Windows by Alawar Entertainment, is precisely such a title. It is a game that wears its inspiration on its lab coat sleeve, a direct descendant of the seminal 1990 Nintendo classic Dr. Mario. Yet, to dismiss Doctris as mere cloning is to miss the quiet, persistent truth of the shareware and casual gaming boom of the early 2000s. This review will argue that Doctris is a fascinating, if technically and culturally modest, artifact—a perfect lens through which to examine the era’s development practices, the relentless churn of the puzzle genre, and the delicate line between homage and derivative work. It represents the democratization of game development in the post-Tetris, post-Dr. Mario landscape, where a single developer could, with modest resources, create a competent and functional entry into a beloved subgenre, finding its audience not on a store shelf but in the digital wilds of download portals.

Development History & Context: One Developer, One Vision

The historical record for Doctris is as sparse as a bacterial culture, but what is revealed tells a clear story. The game was developed by a single individual, Nikolay V. Kuzmin, and published by Alawar Entertainment, Inc., a company that would become a significant force in the casual and “activision-style” shareware market of the 2000s. Released on March 5, 2004, as a downloadable shareware title priced at $19.95 for the “Deluxe” version, its entire distribution model was native to the burgeoning internet.

The Studio & Creator’s Vision: Alawar, during this period, was a prolific publisher of casual puzzle, arcade, and hidden object games. Their model often involved contracting external developers or utilizing internal small teams to produce games that fit established, successful formulas. Nikolay V. Kuzmin, credited as the sole programmer, represents the quintessential “bedroom developer” of the era—a skilled coder capable of implementing a complete game concept without the infrastructure of a large studio. The vision was transparently derivative: create a Dr. Mario-like experience. The official description from multiple sources (MobyGames, IGN, FileGets) is nearly identical, focusing purely on mechanics. This suggests a development process guided by a clear, mechanics-first directive (“make a falling-block color-matching puzzle with a medical theme”) rather than a narrative or artistic ambition.

Technological Constraints & The Gaming Landscape: 2004 was a pivotal year. The casual gaming market was exploding beyond bundled CD-ROMs and into the realm of instant downloads from sites like Big Fish Games, Yahoo! Games, and the publishers’ own websites. The technical “specs” listed—Pentium 300MMX or higher, Windows 95/98/Me/XP/2000/2003—speak to an era of vast compatibility, targeting machines that were already considered slow by cutting-edge standards. The game’s size (noted as 4.1 MB or 3.6 MB) is a stark reminder of the download-speed limitations of the time; a game of this complexity could be delivered in minutes over a 56k modem.

The puzzle genre was, and remains, a bastion of iterative design. Tetris (1984) established the falling-block paradigm. Dr. Mario (1990) added the color-matching elimination and a coherent, thematic wrapper. The early 2000s saw a glut of “falling object” puzzlers (Bust-a-Move/Puzzle Bobble, Magical Drop, Puzzle Quest later on). Doctris entered this crowded field not with innovation, but with a specific, safe pitch: “Dr. Mario, but with a slightly different rule set and available for immediate download.” Its existence is less a creative leap and more a commercial necessity—filling a specific slot in Alawar’s downloadable catalog to capture the player searching for “Dr. Mario similar games.”

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story We Can’t See

This is the section where Doctris reveals its absolute minimalism. The narrative is not a story; it is a setup. The official description, repeated verbatim across MobyGames, IGN, FileGets, and CuteApps, provides the entire narrative thrust:

“Doctor Smith’s laboratory got contaminated by malicious viruses. They are hiding from him in laboratory glassware. Please, help the doctor to disinfect the laboratory and get rid of the viruses, so that he can come back to making his medications to cure the sick. The doctor drops pills inside the flask where the viruses are located to destroy them.”

Plot & Characters: There is no plot. There is a protagonist (Doctor Smith), an antagonistic force (malicious viruses), and a setting (a laboratory). The player is an unseen, unnamed “helper.” Doctor Smith does not appear in the game; his action of “tossing pills” is the game’s core mechanic, but he has no sprite, no dialogue, no presence. The viruses are not characters; they are static, colored obstacles embedded in the “vial” (playing field). There are no cutscenes, no dialogue, no text beyond the title screen and the between-level “stage clear” or “game over” messages. The “story” is a hand-wave to contextualize the gameplay: You are solving a puzzle to progress through “vials” (levels) to “disinfect” a “laboratory.”

Themes: The theme is decontamination through color-coded chemistry. It translates the abstract act of matching colored blocks into a metaphorical medical procedure. The three colors (red, blue, green) represent different “reagents” or “antivirals.” The “pills” are two-part capsules. The underlying, unspoken theme is one of systematic cleansing. The player imposes order (a sterile, cleared vial) on chaos (a messy infection of viruses and falling pills). It is a thematically consistent, if profoundly simple, wrapper. Unlike Dr. Mario, which has a more distinct “virus” sprite and a slightly more developed “Dr. Mario” persona, Doctris strips even this down to bare essentials. The theme of “healthcare” listed in its MobyGames genre tags is accurate but speaks more to the aesthetic dressing than any meaningful engagement with the concept. The game’s narrative is a single-sentence instruction manual, a functional placeholder. Its total absence of narrative depth is, in itself, a defining characteristic—a pure, unadulterated mechanics-focused experience.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Study in Iterative Balance

Here, Doctris has its substance. It is a falling-block, tile-matching puzzle game with a real-time pacing and a fixed, side-view screen. The core loop is identical to its inspirations but with notable, if subtle, variations.

Core Gameplay Loop:

1. A “vial” (a rectangular grid, typically 10×20 in reference to Dr. Mario and Tetris) is populated with a number of stationary, colored “viruses.”

2. A two-segment “pill” falls from the top center of the vial. Each segment of the pill is one of three colors (red, blue, green).

3. The player can move the pill left/right and rotate it (in 90-degree increments).

4. The pill falls at a constant speed (modified by difficulty).

5. The pill stacks on viruses, other pills, or the bottom of the vial.

6. The core objective: Create a horizontal or vertical line of 3, 4, or 5 segments of the same color, including viruses. When such a line is completed, all matched segments and the viruses in that line vanish.

7. If a virus remains unmatched when the vial is full (pills stack to the top), the player fails the level.

8. The goal of each level is to eliminate all viruses. Upon success, the player proceeds to the next, presumably more populated, vial.

Innovative or Flawed Systems:

* The “Line Length” Variant: The most significant rule variation is the difficulty-dependent line length. On Easy, three-in-a-row eliminates. On Medium, four. On Hard, five. This is a profound and clever tweak. It directly scales the spatial puzzle’s complexity. A 3-match is relatively easy to engineer amidst chaos; a 5-match requires building long, contiguous chains and carefully positioning pills over multiple turns. This single change effectively creates three distinct puzzle games within one engine, targeting kids (Easy) and adults (Hard) as the marketing copy claims. It’s the game’s core innovation, demonstrating how a simple parameter shift can drastically alter strategy.

* Mechanical Fidelity: The movement, rotation, and stacking physics are described as behaving “in a manner similar to Tetris pieces.” There is no mention of advanced mechanics like “hard drops,” “soft drops,” or “ghost pieces,” placing it firmly in the classic arcade puzzle school of the early 90s. The pacing is real-time but not “fast”; it is a meditative, strategic puzzle, not a reflex test.

* Lack of Secondary Mechanics: There are no power-ups, no special viruses with unique behaviors (like in some Dr. Mario variants), no combo multipliers, and no chain reaction scoring emphasis described. The focus is purely on the elimination of the set number of viruses. This purity is both a strength (uncluttered design) and a limitation (potential for monotony).

* The “Deluxe” Mode: The “Deluxe” version, referenced in distribution sites like Game-Owl and FileGets, introduces “two new game modes… which means you can play for points!” This is a tantalizing but frustratingly vague detail. The source material does not specify what these modes are. They are likely time-attack or score-attack variants, common in shareware deluxe editions. Their absence from the core description highlights the base game’s minimalist philosophy.

UI & Input: Supported via Keyboard and Mouse. The UI would be extremely simple: a score display, a virus count, the current level, and the playing field. There are no inventories, character sheets, or complex menus. The interface is transparent, a direct conduit between player intention and on-screen result.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Functional Aesthetics

The “world” of Doctris is the laboratory vial. The atmosphere is one of sterile, clinical minimalism.

Visual Direction: The MobyGames specs list “Fixed / flip-screen” and “Side view.” Screenshots, while not deeply described in text, would show a clean, vector-style or simple pixel-art vial against a plain background. The viruses are likely simple, distinct colored blobs or icons. The pills are two-colored rectangles. There is no elaborate animation, no parallax scrolling, no artistic flourish. The art direction is purely functional, prioritizing clear readability of the game state—a necessity in a high-speed puzzle game. It fits the “healthcare” narrative in the most generic way: clean lines, primary colors, a sense of laboratory order. It is the visual equivalent of a well-labeled beaker.

Sound Design: The source material is silent on this front. Given the era (2004), the platform (PC shareware), and the developer (a solo coder), the sound design was almost certainly minimal. We can infer the presence of:

* SFX: Simple, short wave/MIDI sounds for pill movement, rotation, landing, and—most importantly—the satisfying “pop” or “chime” of a line elimination and the “crash” or “shatter” of a virus being destroyed. The feedback loop through sound is critical in puzzle games.

* Music: A single, looping, likely MIDI-based track. It would be inoffensive, possibly melodic or ambient, designed to be unobtrusive during long play sessions. The theme would likely be “upbeat and clinical” or “playfully tense.”

These elements do not “contribute to the overall experience” in a narrative or emotional sense. Instead, they serve the mechanics. The art makes the colors distinct. The sound provides essential cause-and-effect feedback. In a game defined by split-second spatial reasoning, this utilitarian approach is not a flaw but a requirement. The atmosphere is one of focused, quiet problem-solving, not epic adventure.

Reception & Legacy: The Data Vacuum

This is where the historical record collapses. There are no critic reviews for Doctris on MobyGames. The “Moby Score” is n/a. The “Player Reviews” section shows an average score of 3.0 out of 5 based on 1 rating with 0 reviews. This is the epitome of obscurity. The game has been “Collected By” only 2 players on MobyGames. It exists in a state of near-total critical and commercial insignificance.

Contemporary Reception (2004): There is no evidence of any major gaming press coverage. Its existence was confined to the sprawling, algorithm-driven catalogs of download portals (Alawar’s own site, FileGets, CuteApps, MyPlayCity). Its “reception” was purely a function of its ranking in these lists and its download count. The FileProfile data shows “240 Total” downloads at one point, ranking it #13,200 out of 15,688 in its category—a graph of near-invisibility.

Evolution of Reputation & Influence: The reputation has not evolved; it has remained static at “obscure.” It is not cited in academic works (unlike its ancestor Dr. Mario or the canonical Tetris). It is not mentioned in retrospectives on puzzle games. Its influence on the industry is zero. It did not spawn clones, inspire developers, or shift design paradigms. It is a ghost in the machine—a game that successfully executed a known formula and then vanished without a trace, leaving no cultural or industrial footprint.

Its only “legacy” is as a data point. It exemplifies:

1. The shareware/direct-to-download model that flourished in the late 90s/early 2000s before the dominance of App Stores and Steam.

2. The single-developer project made viable by accessible tools and the global reach of the internet.

3. The safe, formulaic design common in the casual game space, where innovation is risk and replication is revenue.

4. The complete disposability of most games in that era’s vast output.

Conclusion: Verdict in the Petri Dish

What, then, is Doctris? It is a competent, functional, and utterly forgettable puzzle game. It succeeds at the primary task set before it: it provides a stable, bug-free (as far as we know) implementation of a Dr. Mario-style falling-block puzzler with a clever difficulty tweak (the variable match length). It is a perfectly serviceable time-waster for a player in 2004 seeking that specific itch.

However, it fails to achieve any form of distinction. It has no identity beyond being a variant. Its presentation is sterile, its narrative nonexistent, its audio/visuals purely utilitarian, and its impact nonexistent. It is the gaming equivalent of a generic pharmaceutical: it contains the active ingredient (the core gameplay loop) and may perform its function, but it has no brand personality, no memorable side effects, and will be forgotten the moment the bottle is empty.

Final Verdict: In the grand museum of video game history, Doctris does not deserve a dedicated exhibit. It is not a masterpiece, a cult classic, or even a noteworthy failure. It is, instead, a perfect specimen of the asymptomatic carrier—a game that demonstrates the health of a robust, commercial puzzle genre ecosystem in the early 2000s, a genre so resilient that it could support countless, nameless entries like this one without collapsing. Its value is purely archival and sociological. To study Doctris is to study the quiet, anonymous, and essential labor that filled the download stores of a bygone internet, a testament to the fact that for every Bejeweled or Zuma, there were a hundred Doctrises quietly cleaning virtual vials in the digital dark. It is a footnote, but a perfectly legible one.