- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Nordic Games GmbH

- Developer: Studio Med-Art

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Secret areas, Shooter, Wave-based combat

- Setting: Gothic, Purgatory

- Average Score: 61/100

Description

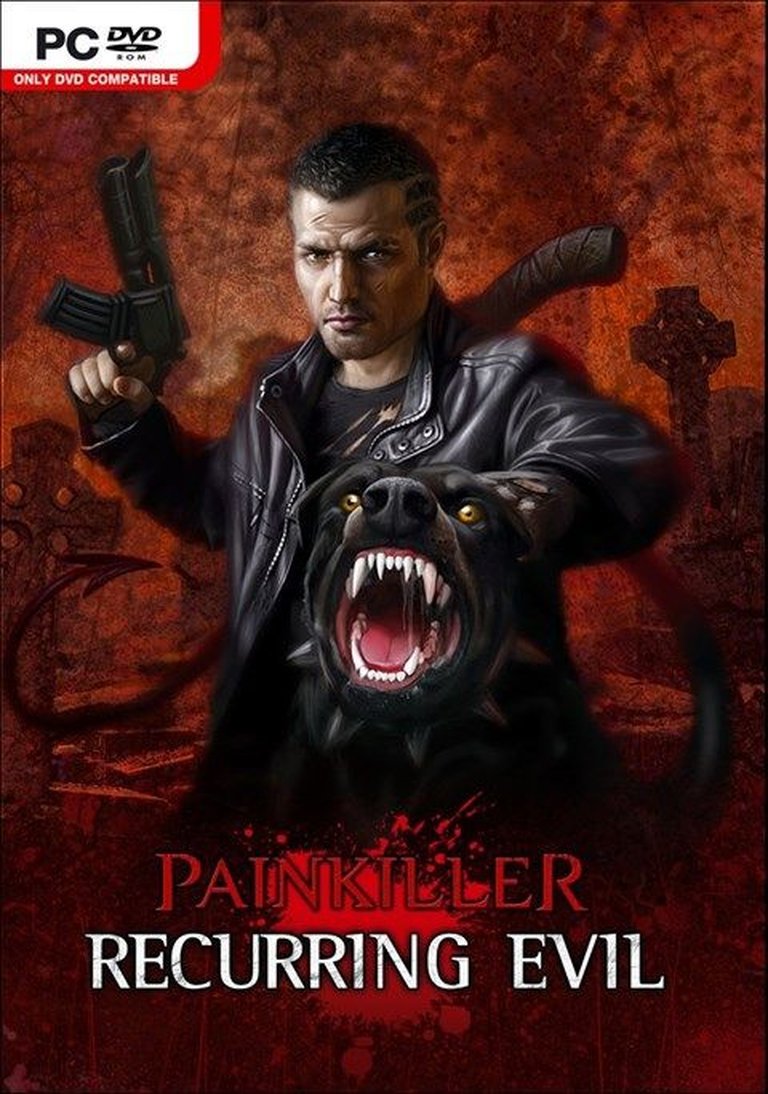

Painkiller: Recurring Evil is a standalone first-person shooter in the Painkiller series, set in a Gothic-inspired version of Purgatory. Following the events of Painkiller: Resurrection, protagonist Bill Sherman, who has become the ruler of Purgatory and wields the powerful Sword of Seraphim, is betrayed by the fallen angel Samael. Samael steals the sword and banishes Bill to various locations within Purgatory, forcing him to battle through dense, action-packed maps filled with waves of demons. The game features a new 5-hour campaign across five maps, emphasizing fast-paced combat, secret areas, and classic shooter gameplay reminiscent of titles like Quake, with improved graphics and a new soundtrack.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Painkiller: Recurring Evil

PC

Painkiller: Recurring Evil Guides & Walkthroughs

Painkiller: Recurring Evil Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (38/100): Painkiller: Recurring Evil is nothing but some sort of “horde mode”, with five levels and thousands of AI-lacking monsters to kill using the same old weapons, with the same old graphics.

gamingpastime.com : Recurring Evil is a very by-the-numbers Painkiller.

gamesreviews2010.com (85/100): Painkiller: Recurring Evil is a solid FPS that is sure to please fans of the genre.

Painkiller: Recurring Evil Cheats & Codes

PC

Press tilde while playing to open the console, then enter the code.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| sv_cheat_godmode_1 | God Mode |

| sv_demon_1 | Demon Mode |

| sv_everything_1 | All Weapons and Ammo |

| sv_keep_decals_1 | Bodies Don’t Disappear |

| sv_less_monster_hp_1 | Monsters at 1 HP |

| sv_max_ammo_1 | Max Ammo |

| sv_max_health_1 | Max Health |

| sv_monsters_always_gib_1 | Monsters Always Explode |

| sv_perfect_finish_1 | Finish Level Perfectly |

Painkiller: Recurring Evil: A Franchise in Purgatory, Trapped in its Own Cycle

1. Introduction: The Horde Awaits (Again)

To understand Painkiller: Recurring Evil is to understand the terminal phase of a once-groundbreaking franchise’s infancy. Released in 2012, this “standalone expansion” arrived twelve years after the original Painkiller reinvented the arena shooter with its heavy metal aesthetic and relentless,horde-based gameplay. By this point, the series had fragmented across multiple studios—People Can Fly, Mindware, Homegrown, Eggtooth, and now Russia’s Med-Art—each tasked with extracting another 5–6 hours of demon-slaying from the same foundational PainEngine. Recurring Evil is not a sequel but a symptom: the sixth major entry in a series that had long since exhausted its creative capital, repackaging recycled assets and familiar mechanics for a dwindling audience of completists. Its thesis is one of cyclical stagnation: just as its protagonist Bill Sherman is doomed to repeat his purgatorial trials, the Painkiller franchise itself is caught in a loop of diminishing returns. This review will dissect how a game with competent, functional design simultaneously exemplifies creative bankruptcy and the irreversible decay of a once-vital formula.

2. Development History & Context: The Franchise Becomes a Factory

The original 2004 Painkiller, developed by Polish studio People Can Fly and published by DreamCatcher, was a revelation. It stripped the FPS genre down to its primordial core—movement, aim, and overwhelming force—wrapped in a gothic-horror-meets-metal aesthetic that felt both nostalgic and freshly brutal. Its explosive success, including a season as the official game of the Cyberathlete Professional League (CPL), spawned an ecosystem of expansions.

By 2012, the development model had shifted. Painkiller: Resurrection (2009) and Redemption (2011) were already “standalone expansions” developed by third-party studios (Homegrown Games and Eggtooth Team, respectively) with varying degrees of official oversight. Recurring Evil was developed by Studio Med-Art (a Russian team) in collaboration with Eggtooth, and published by Nordic Games GmbH (which had acquired the rights from THQ). It was part of a frantic 2011–2012 release schedule that also included Hell & Damnation (a partial remake/sequel by The Farm 51) later that same year.

Technologically, the game runs on the venerable PainEngine, the same middleware-powered engine from 2004. While the source material notes “improved graphics” via higher texture resolutions and more detailed models, this was a cosmetic refresh at best, incapable of masking the engine’s fundamental age. The scripting language was Lua, and sound used the AIL/Miles Sound System, both industry standards but indicative of a project built on legacy foundations, not innovation. The stated goal was clear: deliver a new 5-hour campaign with 5 new, “denser” maps at a budget price ($9.99), leveraging existing assets (weapons, monsters, sound effects) to minimize cost and development time. In context, Recurring Evil is not a new chapter but a factory-line appendix, churned out to keep the brand active during a transitional period for the IP.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Story of Diminishing Stakes

The narrative of Recurring Evil is less a story and more a logistical update on a franchise-wide continuity spreadsheet. It directly continues from the multiple endings of Painkiller: Resurrection and functions as a side-story to Redemption.

Protagonist & Conflict: William “Bill” Sherman, the mobster-turned-Purgatory-warrior from Resurrection, has achieved a bizarre victory: by defeating the corrupted angel Ramiel, he has been anointed Ruler of Purgatory, wielding the divine Sword of Seraphim. This position of cosmic power lasts mere moments. The fallen angel Samael—who had his wings ripped off by Belial in Overdose—appears. In a twist that reeks of narrative convenience, Samael reveals that when Ramiel died, his vast angelic power transferred to Samael. He then steals the Sword of Seraphim from Bill and, in a act of petty cruelty, casts him back into the untamed, unexplored regions of Purgatory to fight anew.

Themes & Execution: The core theme is futility and cyclical violence. Bill is not fighting for a grand cause (like stopping a Hell invasion) or for personal redemption (his initial sin was collateral damage). He is fighting because a powerful being has stripped him of his toy and decided to amuse himself. The “evil” in the title is Samael’s manipulative, game-playing cruelty. The story explores power as a transient, unreliable currency in this afterlife bureaucracy. However, the execution is threadbare. The plot is delivered via two low-budget, text-only “comic” sequences (a step down from Resurrection‘s comic panels). There is no character development for Bill, who remains a monosyllabic vessel for gunplay. Samael is a one-note, gloating villain. The thematic weight of Purgatory as a place of moral reckoning, so prominent in the 2004 original, is entirely absent. Here, Purgatory is just a varied level-select screen.

Canonicity & Resolution: The game’s ending is a direct function of player difficulty, not choice—a bizarre mechanics-over-narrative decision. On normal difficulty, Samael defeats Bill, and he is either killed or rescued (by Belial, from Overdose). On Trauma (hardest) difficulty, Bill somehow overcomes Samael? The source material is contradictory, but the implication is a “good” ending where Bill is saved. This trivializes the conflict. After the cosmic scale of the original Painkiller (preventing a Heaven-Hell war), Recurring Evil stakes everything on a personal grudge match that feels inconsequential. It is a narrative holding pattern, treading water between the larger arcs of Redemption (where Samael would try to rule Hell) and Hell & Damnation.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Relentless, Unchanged Grind

Recurring Evil does not innovate; it reifies. It takes the established Painkiller formula—”run, shoot, collect souls, repeat”—and applies it with rigid fidelity, making only one significant, debated change.

Core Loop: The gameplay is a pure iteration on the 2004 template. Each of the five large maps is divided into arenas separated by shut doors. The player must clear each arena of all enemies (often numbering in the dozens or hundreds per wave) to open the next door and progress. This “lockdown” mechanic is the series’ heartbeat. After clearing a major arena, a checkpoint triggers, the music shifts from the ambient level track to a heavy metal track, health/ammo is replenished, and the path forward opens. Between arenas, players can explore small connective paths for secrets, armor, and tarot cards.

Combat & Arsenal: The player’s toolkit is entirely recycled from previous games. Stakegun, Hellgun, Shotgun, Electrodriver, Rocket Launcher, etc.—all return with their iconic alternate fire modes. The only “new” weapon mentioned in some promotional material (the Hellgun) was actually already present. There is no new weapon. The “demon morph” mechanic, activated by collecting enough souls from slain foes, returns, turning the player into a melee-focused demon for a short duration. This is the sole gameplay innovation since the original, but it’s a direct carry-over from Battle Out of Hell.

Level Design & “Density”: The stated design goal was “more dense” maps with “more action per square meter.” Compared to the sprawling, sometimes confusing open layouts of Resurrection, this is accurate. The maps are more like sprawling, multi-arena labyrinths. Examples from the sources: a gloomy abbey, a jungle-swallowed temple complex, an old warehouse, a destroyed highway full of wrecks, and a final level set in Angkor. Reviews (Gaming Pastime) note this is a strength: “levels are more interesting,” “plenty of ammo,” and “paced better” than Redemption. However, “density” also means tighter corridors and more frequent, sometimes overwhelming, wave spawns. The AI remains rudimentary (“AI-lacking” per Multiplayer.it), with enemies charging directly at the player. No tactical flanking or environmental usage is present.

UI & Systems: The interface is unchanged: a classic FPS HUD with ammo counters, a health bar, a soul counter for demon morph, and a slot for the Black Tarot Cards. These collectible, single-use power-ups (e.g., slow-motion, damage boost) return, with reviewers noting they are easier to acquire here than in previous entries. The menu system and options are notoriously limited; one user review complains of “no graphic options whatsoever,” forcing resolution changes via .ini file edits—a glaring oversight for a 2012 PC release.

The Fatal Flaw: Boss absence. The finale is infamous. The final “boss” is not a boss at all but an invincible environmental hazard—a moving turret or force—that disappears after a set of minions is cleared. As one Metacritic user put it: “the final boss is nothing more than an invincible moving turret.” This epitomizes the game’s lazy design: it cannot even be bothered to script a proper climactic fight.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Gothic Collage

The Painkiller universe has always been a stunning, anachronistic patchwork of historical epochs and architectural styles, all rendered in a hyper-saturated, gothic-horror palette. Recurring Evil continues this tradition but with diminishing visual returns.

Environments: The five levels represent a greatest hits of the series’ settings, slightly remixed:

* The Abbey: Classic gothic stonework, catacombs, stained glass.

* Highway to Hell: A contemporary ruin, cars ablaze, concrete rubble—a nod to the “modern” stages of the original.

* The Warehouse: Industrial, gritty, metal catwalks.

* The Graveyard: A return to the overgrown, misty cemeteries of Painkiller‘s Chapter 2.

* Angkor: The standout. A jungle-choked, rain-swept temple complex with stone ruins, offering a distinct visual identity compared to European gothic.

The “denser” design means these environments are more cluttered with props and set dressing, but the underlying geometry and texture sets are plainly recycled from the original game’s asset library, merely recombined. The PainEngine’s limitations are glaring: flat lighting, low-poly models, and particle effects that haven’t been meaningfully updated since 2004.

Art Direction & Atmosphere: The game successfully maintains the series’ signature tone: a silent, metal-scoredocide. The heavy metal soundtrack (composed by Marcin Czartyński and others for the series, with new tracks here) is a constant, driving presence. It’s brash, aggressive, and perfectly matches the mindless slaughter. However, atmosphere is shallow. Without narrative context or environmental storytelling, the levels feel like aesthetically pleasing death arenas, not places with history or horror. The gothic architecture is just backdrop.

Sound Design: Gun sounds are crunchy and satisfying, a franchise hallmark. Monster roars and screams are recycled stock from 2004. The audio mix is functional but unremarkable, serving the chaotic gameplay without enhancing immersion. The soundtrack remains the primary atmospheric driver.

6. Reception & Legacy: The Sound of a Spent Franchise

Recurring Evil was released into a series already in critical decline and a market moving toward scripted, narrative shooters.

Critical Reception: The reception was poor to mixed, with critic scores averaging 48% on MobyGames (from 2 reviews) and a Metascore of 38 (“Generally Unfavorable”) based on 4 critic reviews. Key criticisms were universal:

* Lack of Innovation: “Troppo poco per un franchise dalle origini così brillanti” (“Too little for a franchise with such brilliant origins”) – Multiplayer.it.

* Recycled Content: No new weapons, enemies, or meaningful assets. “Niente di nuovo” (“Nothing new”).

* Lazy Design: Absence of proper boss fights, simplistic AI, “pessima intelligenza artificiale” (bad AI).

* TechnicalIssues: Performance dips with enemy counts, crashes, and bugs. A notorious lack of graphic options.

* Short Length: The 5-hour campaign, while denser, felt like a “map pack” sold at full price.

One critic (PC Master, Greece) offered a nuanced take: “Recurring evil is not a bad game. It’s just that Painkiller, in its current form, has ran its course.” This captures the essence: it’s a competently built but creatively bankrupt product.

Player Reception: Steam user reviews paint a similarly bleak picture, with a “Mixed” overall rating (43/100) from ~462 reviews as of 2025. The sentiment breakdown shows a stark divide: ~43% positive, ~57% negative. Common praises cite “fast-paced gameplay” and “solid combat” for fans. Common complaints echo the critics: “lack of new content,” “dated graphics,” “performance issues,” “buggy,” and “feels like a mod.” It is viewed strictly as a product for “die-hard fans” or not recommended at all.

Legacy & Industry Context: Recurring Evil has had no meaningful legacy. It did not influence any subsequent games. It is not cited in academic discussions of the FPS genre. Its primary function was as a placeholder. It filled a gap in the release schedule between the poorly received Redemption and the franchise reboot attempt Hell & Damnation (also 2012, developed by The Farm 51 on Unreal Engine 3). The latter’s existence speaks volumes: the series needed a ground-up rebuild on a modern engine, not another PainEngine expansion. Recurring Evil represents the last gasp of the original technical pipeline. Future entries (Painkiller reboot in 2025) have ignored its events entirely.

Historically, it is a cautionary tale about franchise mismanagement. The original 2004 game’s legacy—its pure, unadulterated action, its vibrant level design, its impact on competitive FPS—was being diluted by annual, low-effort expansions recycling the same assets. By 2012, the Painkiller name had become synonymous with “budget, recycled shooter,” and Recurring Evil is a key exhibit in that case.

7. Conclusion: A Verdict for the Already Damned

Painkiller: Recurring Evil is not a bad game in isolation. In its best moments—speeding through the rain-slicked temple corridors of Angkor, mowing down hordes to a blistering guitar riff—it delivers a competent, if dated, simulation of the arcade shooter thrill the series was founded upon. Its level design is a notable improvement over its immediate predecessors, offering better pacing and fewer frustrating dead-ends.

However, to evaluate it solely on that basis is to ignore its context and its cost. Priced at $9.99, it asks for near-full-expansion money for what is functionally a high-quality fan-made map pack. It offers zero new weapons, enemies, or meaningful mechanics. Its narrative is a throw-away vignette. Its technical backbone is a 2004 engine struggling with modern resolutions and multi-core systems. Most damningly, it fails to provide a satisfying climax, offering a finale that is both anti-climactic and technically unfinished.

In the grand chronology of the Painkiller series, Recurring Evil occupies a unique position of * benign mediocrity. It is not the broken mess of *Resurrection nor the insultingly lazy Redemption. It is merely… there. A serviceable, forgettable, 5-hour distraction that demonstrates the franchise had fully consumed itself. The creative well was dry. The engine was obsolete. The story had spun its wheels.

For the historian, Painkiller: Recurring Evil is not a game to study for its design brilliance, but as a primary source document on franchise fatigue. It shows a studio executing a known formula with competent craft but devoid of inspiration, released into a market that has already moved on. Its legacy is that of a stopgap—a brief, unremarkable stay in Purgatory for both its protagonist and the series it serves. The definitive verdict is not that it is terrible, but that it is utterly unnecessary. The true heir to the 2004 throne was not this, but the reboot Hell & Damnation released months later—a game that, for all its own flaws, at least dared to rebuild from the rubble. Recurring Evil merely polishes the same old chains.