- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Browser, Windows

- Developer: Jonas Kölker

- Genre: Puzzle

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Coloring, Grid-based, logic

Description

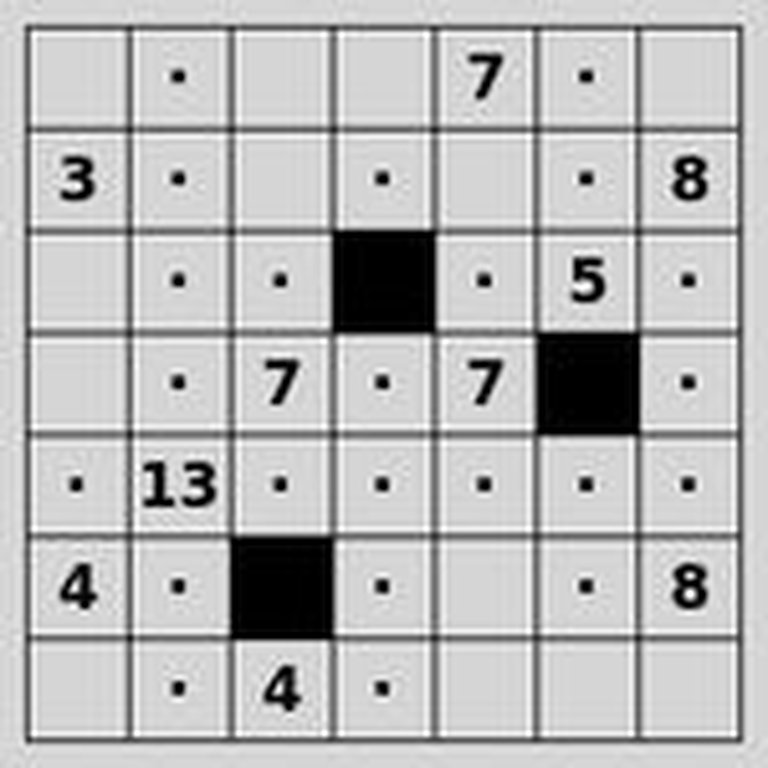

Range is a grid-based puzzle game where players must color specific squares black to satisfy numerical clues that indicate the number of visible squares in all orthogonal directions. The gameplay enforces rules that black squares cannot be adjacent orthogonally and must not isolate any part of the grid, with the grid size freely selectable for added customization.

Where to Buy Range

PC

Range: A Retrospective Analysis of an Obscure Puzzle Gem

Introduction

In the vast and well-documented canon of video game history, certain titles exist in a state of fascinating obscurity—known to dedicated enthusiasts but largely invisible in mainstream discourse. Range, a grid-based logic puzzle released in 2010 as part of Simon Tatham’s Portable Puzzle Collection, is one such title. Its legacy is not one of blockbuster sales or cultural upheaval, but of quiet, elegant design firmly within the tradition of Japanese paper-and-pencil puzzles. This review argues that Range represents a masterclass in minimalist, accessible game design, successfully translating the pen-and-paper logic puzzle “Kurodoko” (also known as “Kuromasu” or “Where is Black Cells”) into a flawless digital format. Its significance lies not in narrative ambition or technological prowess, but in its purity of purpose and its role in preserving and proliferating a niche but intellectually rewarding genre.

Development History & Context

Range exists within a specific and well-defined context: the open-source, cross-platform puzzle ecosystem curated by programmer Simon Tatham. The game was contributed to this collection by Jonas Kölker in 2010, though its true creative lineage traces directly to the Japanese puzzle publisher Nikoli, who originated the “Kurodoko” concept. This places Range firmly in the tradition of “nikoli” puzzles—logic puzzles with strict, simple rules that generate complex, satisfying challenges.

The technological context of its release (2010) was the widespread proliferation of casual and portable gaming, alongside the maturation of open-source software projects. Tatham’s collection, written in portable C, was designed to run on virtually any computing platform, from Windows desktops to Linux terminals and web browsers. Range benefited from this philosophy: it required no flashy graphics, no complex engine, and no online infrastructure. Its development constraints were its strengths—the game’s entire experience is encapsulated in a single set of rules and a grid algorithm. It was created not for commercial acclaim but for utility and accessibility, a digital implementation of a pre-existing analog puzzle form. The “gaming landscape” for Range was not the crowded market of AAA shooters, but the quiet工具栏 of puzzle aficionados and the “time-killer” genre on early smartphones and computers.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Analysis: Range possesses no traditional narrative, characters, dialogue, or themes. It is a pure abstract puzzle, a mathematical construct. This absence is its defining feature. There is no story of a Spartan’s last stand or a Covenant invasion; the only drama is between the player’s logic and the grid’s constraints. The “theme” is pure logic, pattern recognition, and spatial deduction. The satisfaction comes not from plot resolution but from the moment of insight where a black square’s placement becomes logically inevitable. In this, it aligns with the thematic core of all great puzzles: the elegance of a rule-bound system yielding to rational deduction.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Range is a paradigm of a single, deeply integrated mechanic.

- Core Loop: The player is presented with a blank grid (size player-selectable). Some squares contain numbers (1, 2, 3…). The goal is to color certain squares black according to three immutable rules:

- Visibility Rule: Each numbered square must “see” exactly the number of squares indicated, including itself. “See” means having an unobstructed orthogonal (up, down, left, right) line of sight until blocked by a black square or the grid’s edge.

- Isolation Rule: Black squares cannot be orthogonally adjacent (sharing a side).

- Connectivity Rule: Black squares cannot be placed such that they completely partition the white (uncolored) squares into two or more disconnected regions.

- Progression & UI: Progression is purely level-based. The player selects a grid size (e.g., 5×5, 10×10, 20×20), and a new randomized puzzle is generated. The interface is the epitome of “point and select”—click to turn a square black, click again (or use a tool) to mark it as a known white square (often with an ‘X’). There are no lives, no timers, no penalty for incorrect marks in most implementations (allowing for pure experimentation). The innovation is not in adding features, but in the flawless, unambiguous implementation of the three rules, often with visual cues (e.g., numbers turning red if their current visible count is too high).

- Systems Analysis: The game’s brilliance is in its systemic interplay. A number like ‘5’ in a 5×5 grid is an immediate anchor—it must see all squares in its row and column, meaning those entire lines must be white, forcing all other squares in those lines to be black under the isolation rule. Lower numbers create chains of deduction. The connectivity rule is the masterstroke, preventing brute-force solutions and ensuring global logic. A flaw? None inherent. The difficulty scales purely with grid size and number distribution, and the puzzle generation algorithm (as part of Tatham’s collection) is renowned for producing valid, unique, and solvable puzzles.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Range has no world, no art, and no sound in a conventional sense. Its “setting” is the grid itself—an abstract plane. The “atmosphere” is one of concentration and quiet logic. Visually, it is stark: a monochrome (or limited color) grid on a solid background. This is a strength, not a weakness. The visual direction is pure functionalism; every pixel serves the clarity of the puzzle state. There is no distraction. Sound design is typically absent or limited to optional, minimalist click cues. The overall experience is deliberately sterile, forcing all engagement onto the mental model of the grid. This contributes to its timelessness; a Range puzzle from 2010 is identical in experience to one played today.

Reception & Legacy

Reception: MobyGames records a minuscule footprint: two player ratings averaging 4.7/5 (as of the provided data), and zero critic reviews. This is expected for a niche puzzle within a niche collection. It flew under the radar of every major publication. Its “reception” is that of a beloved tool within the puzzle community, a standard recommendation for fans of grid logic games like Minesweeper, Hitori, or Nurikabe.

Legacy & Influence: Range‘s legacy is twofold and entirely positive:

1. Preservation & Propagation: As part of Simon Tatham’s Portable Puzzle Collection—a seminal, widely ported, and permanently free/open-source suite—Range (as “Kurodoko”) has been maintained, translated, and made available on countless platforms for over a decade. It has introduced thousands to the puzzle type who may never have encountered Nikoli’s original print collections. It is a canonical example of digital puzzle preservation.

2. Genre Integrity: It represents the “correct” way to digitalize a paper puzzle: no monetization, no extraneous features, no paywalls, just pure, clean logic. It stands in silent contrast to the myriad “freemium” puzzle games that clutter app stores, demonstrating that a great puzzle needs no progression systems, coins, or lives—only a sound rule set.

It has no influence on the broader video game industry, which is not its domain. Its influence is within the subculture of puzzle design, serving as a reference implementation.

Conclusion

Range is not a “game” in the narrative-driven, spectacle-oriented sense that dominates historical analysis. It is, more precisely, a tool for engaging with a specific form of logic puzzle. Its place in video game history is as a testament to the enduring power of minimalist design and open-source philosophy. It is a ghost in the machine—a game with no marketing budget, no cultural footprint, and no sequel, yet perfectly fulfilling its purpose for anyone who seeks it out.

Final Verdict: A masterpiece of its obscure genre. Range is an indispensable, flawless implementation of a classic logic puzzle. It is historically significant not for changing the medium, but for perfectly embodying one of its purest forms: the rules-based, thought-alone experience. It receives a full score within its own context, but that context is deliberately narrow. For the vast majority of gamers, it will remain an unknown gem; for the puzzle enthusiast, it is an essential, timeless classic.