- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: agagames.com

- Developer: agagames.com

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Point-and-click

- Setting: Zombies

Description

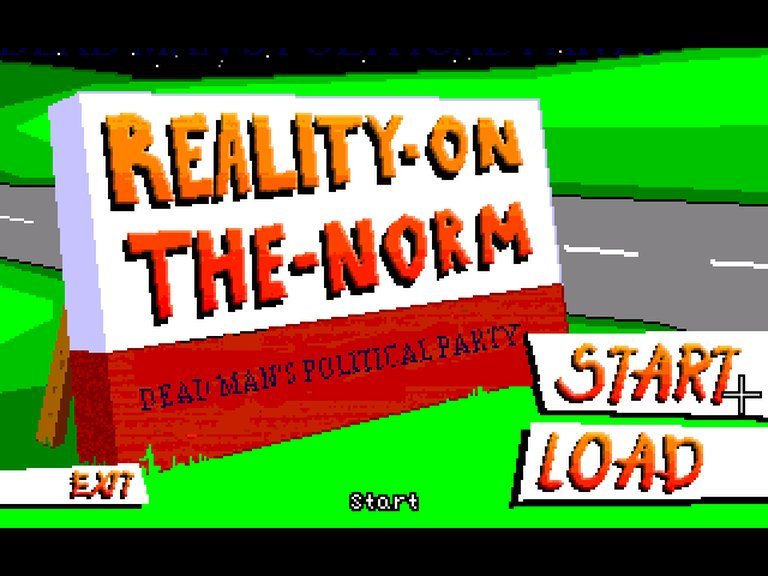

Dead Man’s Political Party is a comedic graphic adventure game set in the satirical town of Reality-on-the-Norm, where players assist Zombie Michael Gower, under the guidance of Mr. Reaper, in his four-day campaign to become mayor against the corrupt Baron Wolfgang. Using point-and-click mechanics with specific mouse commands, players explore environments, solve puzzles, and interact with characters to navigate this absurd political landscape.

Dead Man’s Political Party Free Download

Dead Man’s Political Party: A Critical Necropsy of an Indie Adventure Game Artifact

Introduction: The Unliving Pulse of Indie Gaming

In the vast, digitized catacombs of video game history, certain titles emit a faint, persistent signal not of commercial triumph or critical canonization, but of sheer, unadulterated creative will. Dead Man’s Political Party (2003) is one such title—a ghost in the machine of the early 2000s indie scene, a game so obscure it exists on the precipice of oblivion, yet whose very existence tells a richer story about community, tooling, and the democratization of narrative design than many hyped blockbusters. Developed for the freeware adventure game engine Adventure Game Studio (AGS) and released into the wilds of the “Reality-on-the-Norm” (RON) shared universe, this point-and-click oddity is not merely a game about a zombie mayoral campaign; it is a time capsule of a specific, fervent moment in gaming culture. This review posits that Dead Man’s Political Party’s ultimate significance lies not in its mechanics or its plot, but in its role as a vital, participatory node within a grassroots creative ecosystem. It represents the enduring power of niche toolkits to foster surreal, personal, and politically satirical stories that stood in stark, wonderful contrast to the increasingly homogenized mainstream of its era.

Development History & Context: Engineered in the AGS Foundry

The Studio and the Series: agagames.com and the RON Multiverse

The game springs from the mind of Berian Morgan Williams, operating under the banner agagames.com. This was not a studio in the conventional sense but a personal project handle, typical of the early 2000s ” bedroom developer” phenomenon. Williams was a prolific contributor to the Reality-on-the-Norm series—a collaborative, open-world narrative experiment where multiple creators contributed adventures set within the same bizarre town, sharing characters and a loosely defined canon. Dead Man’s Political Party itself is a direct sequel to MI5 Bob: The Uplift Mofo Party Plan (2003) and precedes Before the Legacy (2003), placing it squarely in the most active period of the RON project. This serialized, community-driven approach to world-building was a precursor to modern transmedia storytelling, executed on a shoestring budget with maximalist creative ambition.

The Technological Crucible: Adventure Game Studio in 2003

The game’s technical DNA is inextricably linked to Adventure Game Studio (AGS), the free, Windows-based engine created by Chris Jones. By 2003, AGS was maturing from a niche tool into the de facto standard for amateur and semi-professional 2D adventure game development. Its significance cannot be overstated: it provided a accessible framework for graphics, inventory, dialogue trees, and scripting, effectively democratizing game development. For Dead Man’s Political Party, this meant:

* A side-view, 2D pixel-art aesthetic enabled by AGS’s rendering pipeline.

* A point-and-click interface leveraging standard mouse commands—left click to walk, double-click to interact, right-click to examine or talk—that was both intuitive and a direct legacy of LucasArts and Sierra classics.

* Scriptable game logic allowing for the day-by-day progression and puzzle integration central to the adventure gameplay.

The constraints of AGS—limited color palettes, fixed resolutions, and a reliance on manually created art assets—were also its strengths, enforcing a design philosophy of cleverness over graphical horsepower.

The 2003 Gaming Landscape: An Island of Surrealism

Dead Man’s Political Party emerged in a year dominated by sequels (The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Mario Kart: Double Dash!!) and the rising tide of online multiplayer (the Battlefield and Call of Duty series). Against this backdrop, the game was a defiantly single-player, narrative-driven, and wilfully odd experience. It shared release space with other notable AGS titles like Chzo’s Myth series and Ben Jordan: Paranormal Investigator, carving out a space for horror, comedy, and surrealism that major publishers largely ignored. Its existence is a testament to the vibrant, self-sustaining ecosystem that flourished outside the spotlight, powered by forums, fan sites like the Reality-on-the-Norm wiki, and the simple joy of making and sharing.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Campaign from the Crypt

Plot Mechanics: Four Days to Eternity

The narrative is elegantly simple in premise yet expansive in execution. The player has four in-game days to assist Michael Gower, a zombie inexplicably running for Mayor of the town Reality-on-the-Norm. His campaign is managed by the chillingly pragmatic Mr. Reaper (a personified Grim Reaper), and his opponent is the corrupt Baron Wolfgang. The objective is to navigate the town, gather resources, sway voters, and sabotage the Baron, all while managing the unique “challenges” of being a reanimated candidate. The four-day structure provides a natural act breakdown, creating pacing and urgency rare in casual adventure games.

Character & Dialogue: Theolitics of the Undead

Dead Man’s Political Party excels in its character writing, using its absurdist premise to deliver sharp satire.

* Michael Gower is not a mindless monster but a surprisingly earnest, if decomposing, everyman. His desire to serve the living community despite his undead state is the game’s emotional core, exploring themes of redemption, citizenship, and what it means to be “of” a community.

* Mr. Reaper is the perfect campaign manager: efficient, morally flexible, and utterly without sentiment. He represents the bureaucratic, impersonal forces that underpin all political machinery, providing much of the game’s deadpan humor.

* Baron Wolfgang is the quintessential corrupt incumbent—likely a vampire or other aristocracy-parody—embodying entrenched power, backroom deals, and exploitation.

The dialogue, while constrained by the typical AGS conversation trees, is witty and filled with puns rooted in the undead/political lexicon (“campaign trail,” “grassroots movement,” “swing states”). The supporting cast—from alley bums to jailors—populates a world that feels uniquely RON, a place where the supernatural is mundane and politics is a constant, chaotic street performance.

Underlying Themes: More Than a Zombie Joke

Beneath the comedy, the game interrogates several potent ideas:

1. Death and Democracy: Can the dead have a stake in the living world? Is Gower’s candidacy a form of resurrection or a hijacking? The game subtly asks who gets to participate in civic life.

2. Corruption vs. Outsiderism: Wolfgang represents corrupt, familiar power; Gower, for all his grotesquery, is an outsider promising change. The satire targets political theater itself, where image (a zombie’s rotting face) can be both a liability and a shocking asset.

3. The Banality of Evil (and Bureaucracy): Mr. Reaper’s matter-of-fact approach to electoral manipulation—stealing votes, threatening opponents—frames political corruption as a routine administrative task, a profoundly cynical and hilarious observation.

The title’s source, Oingo Boingo’s “Dead Man’s Party,” is thus not just a cute reference but a thematic thesis: this is a celebration (a “party”) of the dead asserting their presence in the world of the living, with all the attendant awkwardness and subversion.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The AGS Cadence

Core Loops and Puzzle Design

Gameplay conforms to the classic graphic adventure template. The player explores static, hand-drawn screens (Scid’s bar, the town square, Michael’s house, the morgue, the jail), accumulates inventory items (a guitar, a metal detector, a strange machine), and engages in dialogue to progress. The puzzles are inventory-based and environmental, requiring the player to:

* Combine items in non-obvious ways (e.g., a guitar and a “strange machine”).

* Use items on specific scene hotspots to bypass obstacles or acquire new items.

* Manipulate characters through dialogue or by providing them with items to gain information or assistance.

The “four days” structure is the primary innovative mechanic. Certain actions or puzzles are only available on specific days, and the player’s choices can alter the availability of locations or characters later. This introduces a degree of branching and consequence, though within the linear constraints of a short adventure game. Failure to complete a key task by day’s end likely leads to a game-over or a “bad ending,” encouraging multiple playthroughs—a hallmark of the genre.

Interface and User Experience

The four-command mouse interface (walk, get/use, look, talk) is implemented cleanly and is instantly comprehensible to adventure veterans. The UI is minimal, with inventory and verb menus typically hidden or context-sensitive, maximizing screen real estate for the 2D art. This simplicity is a strength, avoiding the verb-heaviness of older Sierra games. However, without a in-game hint system (common in later AGS titles), the game likely relies on period-appropriate player intuition and, in the modern era, community-written walkthroughs—a barrier to entry for contemporary players.

Strengths and Flaws: A Product of Its Tools

Strengths:

* Pacing: The day structure provides natural narrative beats.

* Coherence: The puzzles and plot are tightly coupled; you generally perform actions that directly further the campaign goal.

* Character-Driven Puzzles: Many puzzles involve helping or tricking specific town denizens, reinforcing the world-building.

Flaws (inferred from design and era):

* Pixel-Hunting: Like all AGS games of the period, small, non-obvious clickable hotspots can lead to frustration.

* Obscure Logic: Some combinations may follow the developer’s personal logic rather than universal adventure game logic.

* Linear Bottlenecks: Despite the day structure, there is likely a critical path with little in the way of truly open-ended solutions.

* Lack of Modern Polish: No voice acting, static backgrounds with minimal animation, and a lack of quality-of-life features expected post-2005.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Texture of Reality-on-the-Norm

Setting and Atmosphere: The Weird Normal

“Reality-on-the-Norm” is the key concept. It is not a fantasy world but our world with a persistent, low-grade weirdness dialed up. The town is mundane in its architecture—bars, stores, a town square—but populated by zombies, reapers, vampires, and other “norms.” This juxtaposition creates a unique, subtly unsettling atmosphere. The game’s world is dyseptic optimism: a cheerful, cartoonish surface (bright colors, goofy character sprites) over a foundation of death, corruption, and bureaucratic horror. The player is not saving the world from annihilation but rigging a local election—a brilliantly mundane goal for an absurdist setting.

Visual Direction: The AGS Aesthetic

The art is pure early-2000s AGS: 320×200 resolution (or similar), dithering for shading, and a limited palette. Screenshots show a functional, expressive style. Character sprites are simple but animated (shuffling walks, gestures). Backgrounds, likely painted by Francisco González (Grundislav) and Cato Blostrup (Esseb) based on credits, convey a clean, semi-detailed look that prioritizes readability over realism. This “retro” style is not a nostalgic imitation but a necessity of the tool, and it perfectly suits the game’s tone—a world that feels both old and perpetually stuck in a slightly off-kilter present.

Sound Design and Music: A Curated Eclecticism

The sound design is where the game punches above its weight class. The licensed soundtrack is a bold, anachronistic, and thematically resonant choice for a freeware game:

* Oingo Boingo’s “Dead Man’s Party” (title track): The ironic, new-wave anthem sets the perfect tone.

* The Cranberries’ “Zombie”: Directly references the protagonist’s state.

* U2’s “Wake Up, Dead Man”: A somber, spiritual track.

* Queen’s “Death on Two Legs”: A vicious rocker attacking a “dirty, dirty” figure—perfect for Baron Wolfgang.

* Jelly Roll Morton’s “Dead Man’s Blues”: Adds period authenticity and melancholy.

* Kernkraft 400’s “Zombie Nation”: A techno track that likely plays during chaotic scenes.

The use of these well-known songs (from artists spanning 1920s blues to 1990s alternative rock) creates a sonic collage that is jarring, funny, and oddly cohesive. It elevates the game from a pure AGS product to something that feels like a mixtape come to life. The “Reality-on-the-Norm theme” by Mark J. Lovegrove provides a unifying, quirky leitmotif. This auditory layering is the game’s most professional and memorable feature, demonstrating a curation skill that compensated for limited original composition resources.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Cult

Contemporary Reception: A Whisper in the Forums

Dead Man’s Political Party left virtually no footprint in the mainstream gaming press. MobyGames shows a single player collection and an average score of 2.6/5 from that one rating—statistically meaningless. There are no critic reviews on record. Its “reception” was confined to the AGS forums, the Reality-on-the-Norm community hubs, and file-hosting sites. It was a piece of fan service for a specific niche: players who followed the RON series or were deeply embedded in the AGS scene. Its release was an event for hundreds, not millions.

Evolving Reputation: From Obscurity to Artifact

Its reputation has not so much evolved as solidified into a historical artifact. Today, it is rarely discussed outside of deep-dive retrospectives on AGS history or the RON series. Its value is now primarily:

1. Archival: As a preserved example of early 2000s AGS game design, available on the Internet Archive.

2. Scholarly: As a case study in grassroots world-building and the use of licensed music in hyper-low-budget development.

3. Cult: For a handful of nostalgic RON fans, it remains a beloved, quirky chapter in an ongoing inside joke.

The single, out-of-context Reddit comment praising a story from Dead Man’s Party is almost certainly a misattribution—likely referring to The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt‘s “Dead Man’s Party” quest. This confusion itself speaks to the game’s obscurity: its title is evocative enough to be misremembered in connection with more famous works.

Influence and Industry Impact: The Ripple in the Pond

Dead Man’s Political Party had zero measurable influence on the broader games industry. It did not inspire clones, affect major design trends, or reach an audience beyond the AGS community. Its influence is microscopic and community-bound:

* It contributed to the living tapestry of Reality-on-the-Norm, proving the series could handle political satire within its universe.

* It demonstrated the flexibility of AGS for thematic variety—from paranormal investigation (Ben Jordan) to zombie political comedy.

* It is a data point in the history of freeware and shareware, showing that complete, quirky games could be made and distributed with no profit motive, purely for creative expression.

In the grand narrative of game history, it is a sub footnote. But in the specific history of passion-project game development, it is a perfectly preserved specimen.

Conclusion: A Ballot for the History Books

Dead Man’s Political Party is not a forgotten classic. It is not a flawed masterpiece. It is, by any mainstream metric, a forgotten artifact. Yet, to dismiss it is to miss its profound historical utility. It stands as a pristine example of a specific creative moment: the early 2000s explosion of accessible game engines that empowered a generation to build their own bizarre worlds. Its narrative—a zombie running for office—is a perfect metaphor for the AGS scene itself: something dead (the commercial adventure genre) given new, unexpected life through sheer communal force of will.

The game’s technical execution is competent yet dated. Its puzzles are of their time. Its reach was microscopic. But its heart—the audacious idea to merge political farce with the supernatural within a shared, community-owned universe—is undeniably charming. The painstakingly curated soundtrack alone speaks to a passion that transcended its budget.

Final Verdict: As a game to play today, Dead Man’s Political Party is a curiosities cabinet piece—interesting for its concept and context, but clunky by modern standards. As a historical document, however, it is invaluable. It is a textbook chapter on the “long tail” creativity that thrived in the pre-Steam, pre-Early Access era. It represents the triumph of niche community over mass appeal, of surreal satire over safe mechanics, and of a free engine over a AAA budget. In the annals of video game history, it does not deserve a spot on the “Greatest of All Time” lists. It deserves a spotlight in a museum exhibit titled “The Underground Gardens: How Amateur Tools Grew Worlds.” For that, it is not just a game; it is a testament. It casts its vote for creativity, and in that race, it wins by a landslide.