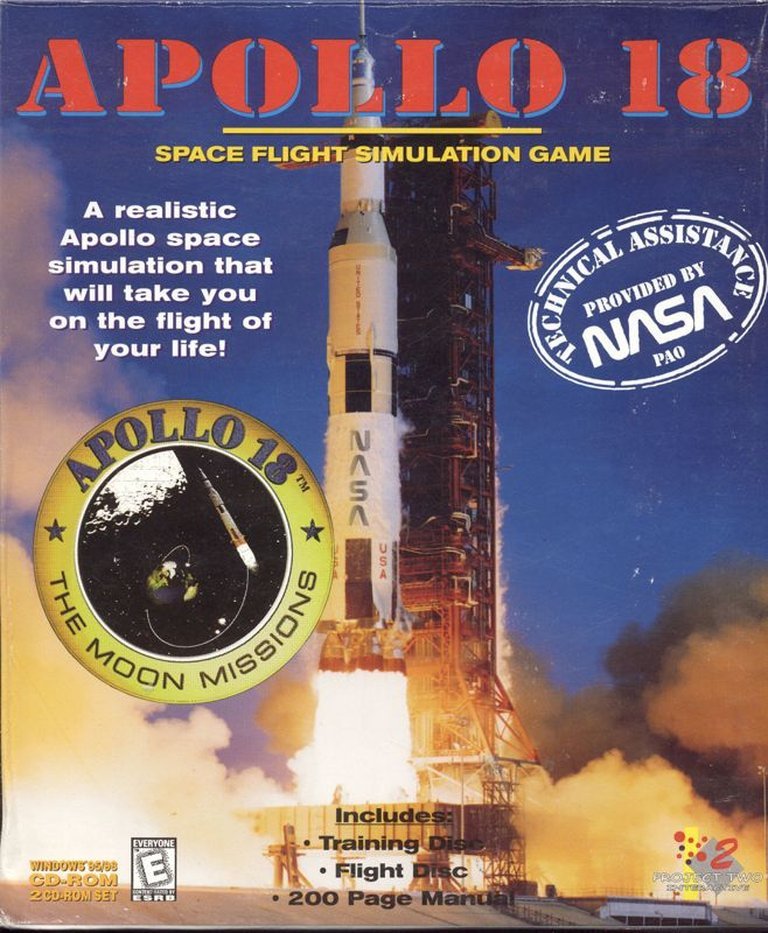

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Project Two Interactive BV

- Developer: AIM Software Ltd.

- Genre: Aviation, Flight, Simulation, Vehicular

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade sequences, Command-based, Sequence accuracy, Simulation

- Setting: Earth’s Moon

- Average Score: 42/100

Description

Apollo 18: The Moon Missions is a realistic simulation game that recreates the Apollo lunar mission experience, starting with intensive training at Johnson Space Center via video-heavy orientation. Players must learn and execute precise commands and sequences to progress to the Apollo 18 launch, then spend most of the mission managing control panels and readouts on the shuttle to the Moon, with occasional arcade interludes and challenges like radio interference, emphasizing accuracy over flashy gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Apollo 18: The Moon Missions Reviews & Reception

ign.com (42/100): Turns out 4000 feet per second is pretty boring without any windows.

retro-replay.com : Apollo 18: The Moon Missions delivers a rigorous and methodical gameplay experience that caters to spaceflight enthusiasts and simulation purists.

Apollo 18: The Moon Missions: Review – A Monument to Flawed Authenticity

Introduction: The Allure and Agony of Hyper-Realism

In the landscape of 1990s PC gaming, where flight simulators like F-15 Strike Eagle and space epics like X-Wing cultivated dedicated followings, Apollo 18: The Moon Missions arrived in 1998/1999 with a singular, uncompromising promise: to simulate the experience of commanding a real Apollo mission with NASA-grade fidelity. Developed by the modest American studio AIM Software and published by the Dutch outfit Project Two Interactive, the game was not merely an entertainment product but an ambitious educational simulator. Its legacy, however, is a stark case study in the perils of prioritizing authenticity above all else. This review will argue that Apollo 18 is a fascinating but fundamentally broken artifact—a game whose profound respect for historical procedure crippled its viability as a playable experience, earning it one of the most scathing critical receptions of its era while cementing its status as a cult object for simulation purists.

Development History & Context: Ambition in the Late-’90s Sim Boom

Studio Vision and Constraints: AIM Software, led by producer and designer Allan Kuskowski, was a small studio with a clear niche. Their prior work, visible in the credits for titles like F/A-18 Hornet 3.0 and various obscure simulations, suggests a team fascinated by complex systems but operating on a limited budget. Apollo 18 was conceived during the tail end of the CD-ROM boom, when multimedia “edutainment” and high-fidelity simulators often coexisted in the same product. The decision to split the game across two CDs—one for a video-heavy “orientation” and one for the simulation—was both a technical necessity (to store the大量 video footage and detailed assets) and a structural statement about its dual nature as training tool and game.

The Gaming Landscape: The late 1990s saw a segmentation in the simulation market. On one hand were accessible arcade-style flight games; on the other were impenetrable “hard sims” like Digital: A Love Story or the burgeoning Microsoft Flight Simulator series, which demanded extensive manual study. Apollo 18 squarely aimed for the latter category, betting that the prestige of the Apollo program and the promise of total realism would attract a dedicated, patient audience. Its release in 1999 placed it alongside titans like Microsoft Flight Simulator 98 and mere months before the revolutionary Microsoft Space Simulator, creating a crowded field where realism was a baseline expectation, not a differentiator.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story is the Procedure

Apollo 18 possesses no traditional narrative with characters, cutscenes, or dramatic plot. Its “story” is the Apollo mission itself—a procedural, historical narrative of launch, translunar injection, lunar orbit, descent, and return. The player assumes the role of the unnamed Commander, tasked with executing a fictionalized Apollo 18 mission.

Themes of Procedure and Memory: The game’s core thematic tension is between systematic, checklist-driven order and the chaos of potential failure. The narrative unfolds through:

* Mission Control Dialogues: Text and voiced updates that guide (or mislead, during “radio interference”) the player.

* Logbook Entries: The player’s own actions create a procedural narrative.

* Environmental Storytelling: The meticulously recreated control panels and readouts are the story. Successfully completing a phase—achieving orbit, performing a docking burn—is the narrative climax.

There is no villain but physics and human error. The underlying theme is a quasi-religious reverence for process, echoing the historical Apollo program’s culture of “failure is not an option.” The game posits that the heroism of spaceflight lies not in dogfights but in flawless execution of thousands of mundane steps, a stark contrast to the cinematic space operas dominating popular culture.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Grind of Godlike Precision

This is where Apollo 18‘s philosophy clashes catastrophically with交互 entertainment principles.

Core Loop and The “Checklist Simulator”: The gameplay is a relentless cycle of: 1) Receive a command from Mission Control (e.g., “Initiate fuel cell purge sequence”). 2) Consult the 200+ page manual (or your memory). 3) Physically click the correct toggle switch on the 2D panel or type the precise keyboard command. 4) Verify readouts change correctly. 5) Wait for the next command. This loop persists for hours across the launch, coast, and landing phases. The “game” is essentially an interactive technical manual.

The Radio Interference Mechanic: A nominal innovation, “radio interference” periodically obscures Mission Control’s instructions, forcing the player to recall the next step from memory. Instead of creating tension, this mechanic almost universally induces panic and frustration, as a single forgotten step dooms the mission. It amplifies the game’s punishing difficulty but highlights its lack of a forgiving learning curve.

Arcade Sequences: Tokenistic Breaks: Brief, simple arcade minigames interrupt the monotony—a rudimentary docking alignment challenge or a radar tracking task. Far from being engaging diversions, these feel like afterthoughts, disconnected from the simulation’s rigor and often implemented with clunky controls. They serve only to underscore how alienating the main simulation is by comparison.

UI and Systems: A Masterclass in Inaccessibility: The interface is a double-edged sword. Visually, it looks authentic—a dense forest of switches, lights, and numerical displays. Functionally, it is a nightmare. There is no in-game context-sensitive help. Critical systems like the RCS (Reaction Control System) thrusters or gimbal angles require memorization of specific codes. Players report failing the launch sequence because they “set the gimbal improperly” despite inputting the values Houston provided—a sign of either obscure logic or buggy implementation. The game provides a checklist but no feedback on why a step failed, leading to brute-force trial and error.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Authentic Atmosphere, Failed Execution

Visuals: The game’s aesthetic is one of stark, documentary realism. The orientation disk uses low-resolution, grainy video footage sourced from NASA archives, effectively evoking the 1960s/70s broadcast aesthetic. The simulation disk’s panels are crisp 2D renders with clear, period-accurate labeling. There are no 3D views of the spacecraft exterior; your entire world is the cockpit. This is a strength for authenticity but a fatal flaw for engagement—the “world” is a spreadsheet. Occasional wireframe models during docking are primitive even for 1998.

Sound Design: Sound is almost entirely diegetic. You hear the hum of systems, the beep of alerts, and the crackle of Mission Control’s voice. There is no musical score, which reinforces the clinical, operational tone. However, the audio implementation is often cited as sparse and unhelpful—critical warning tones are not distinct enough, and voiceovers can be muffled, exacerbating the radio interference problem.

Atmosphere vs. Engagement: The world-building succeeds in creating a feeling of being inside a complex machine. It is immersive in the sense of sensory deprivation and procedural focus. However, this atmosphere is antithetical to the “game” part of “video game.” It creates tension through confusion and boredom, not through stakes or narrative investment.

Reception & Legacy: A Critical Catastrophe and a Cult Curio

* contemporary Reception:* The critical response was savagely negative, ranking among the worst-reviewed games of its time.

* German Press (the loudest critics): Magazines like PC Action (9%), PC Games (9%), GameStar (8%), and PC Player (17%) universally panned it. Common complaints: “sterile,” “boring,” “requires a 200-page manual,” “the worst game of the year,” “like watching a test pattern.” PC Joker succinctly stated it was “Realismus… for the developer, for everyone else the most boring game in the world.”

* Anglophone Press: GamePro (US) gave it 1/5 stars, calling it “a mess.” IGN noted it left “feelings of boredom and frustration.” The lone positive outlier was the Danish Privat Computer PC, which awarded it 72% precisely because of its authenticity and monotonous, “robot-like” gameplay, praising it as a genuine simulation.

* Player Reception: MobyGames records an abysmal player average of 2.1/5 (based on a tiny sample). Today, on abandonware sites, comments revolve around technical struggles to run it on modern systems and the desperate search for the indispensable manual.

Evolving Legacy: Apollo 18 has not been rehabilitated. It remains a notorious example of simulation gone too far. Its influence is primarily negative—a cautionary tale about the balance between simulation depth and playability. It is referenced in discussions about “simulation purgatory” and games that mistake complexity for depth. Its preservation on abandonware sites is driven not by love, but by historical curiosity; it is a museum piece of design extremism. The fact that a manual is required to play it at all makes it an outlier in an era of in-game tutorials.

Conclusion: A Flawed Monument to a Forgotten Ideal

Apollo 18: The Moon Missions is not a “good game” by any conventional metric. It is tedious, frustrating, visually sparse, and demands a level of INVESTMENT—in time, in study, in patience—that few players possess or should be expected to give. Its 22% aggregate critic score is not merely deserved; it is a testament to its catastrophic failure as a commercial entertainment product.

Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to ignore its strange, audacious heart. It is one of the few games that genuinely attempts to simulate the cognitive labor of a highly technical profession. Its reverence for the Apollo program’s procedural heritage is almost awe-inspiring in its purity. In its broken way, it achieves a unique form of immersion: the player isn’t just feeling like an astronaut; they are thinking like one, trapped in a loop of verification and command.

Its place in history is not as a classic, but as a critical boundary marker. It defines the outer limit of how far realism can be pushed before the “game” evaporates entirely. For game historians, it is an essential study in design myopia. For the tiny handful of players who mastered it, it is a secret badge of honor—a private journey to the moon that no one else was patient enough to take. For everyone else, it remains a curious, dusty artifact: a monument to a noble but fatally flawed vision of what a video game could be.

Final Verdict: A historically significant failure. Avoid as a game, study as a lesson.