- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Cendant Software Deutschland GmbH

- Genre: Compilation

Description

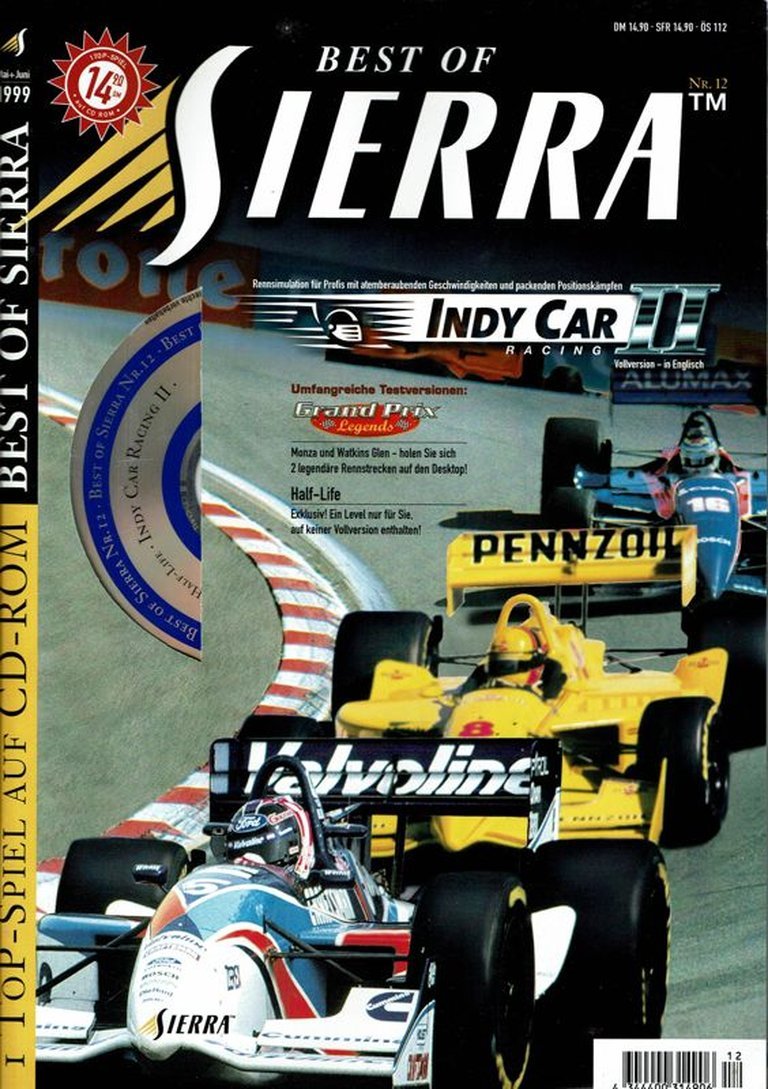

Best of Sierra Nr. 12 is a 1999 Windows compilation CD that serves as the May/June issue of the Best of Sierra series, centering on the full version of IndyCar Racing II—a realistic open-wheel racing simulation set in the IndyCar circuit—while also including exclusive demos of the historic Formula 1 title Grand Prix Legends and the groundbreaking sci-fi shooter Half-Life, showcasing Sierra Entertainment’s diverse game offerings from that era.

Best of Sierra Nr. 12 Reviews & Reception

reddit.com : Golden Age of Sierra, imo: 1992-1993.

retro-replay.com : The Best of Sierra: 12 Top Games compilation delivers an impressive variety of gameplay styles drawn from Sierra’s golden age.

Best of Sierra Nr. 12: Review — A Time Capsule in a CD-ROM Tray

Introduction: The Curator’s Dilemma

To review Best of Sierra Nr. 12 is not to review a single game, but to dissect a deliberate fragment of interactive history—a curated snapshot of a legendary publisher at a pivotal, tumultuous moment. Released in May/June 1999, this issue of the Best of Sierra series arrives not as a cohesive experience but as a historical artifact, a “value pack” embodying the final, uncertain gasp of an era. Its thesis is one of transition: it captures Sierra On-Line (soon to be Sierra Entertainment) as it shifted from premier developer to a beleaguered publisher, its legendary creative engine running out of steam even as its brand name retained immense cachet. The compilation’s true substance lies not in its titular full game, IndyCar Racing II, nor its demo offerings, but in its very existence as a commercial product—a nostalgic, budget-priced time capsule aimed squarely at a PC gamer’s yearning for a simpler, more curated past.

Development History & Context: Sierra at the Edge of the Millennium

The Studio and the Strategy: By 1999, the Sierra of Ken and Roberta Williams’s founding vision was a ghost haunting a sprawling corporate entity. After a series of mergers (CUC, Cendant, Havas, Vivendi), layoffs (including the shuttering of iconic studios like Yosemite Entertainment and Dynamix), and strategic pivots, Sierra’s identity was fractured. The Best of Sierra series itself was a calculated re-packaging exercise. Managed by Cendant Software Deutschland GmbH for the European market, these compilations repackaged earlier “issue” bundles (like Best of Sierra: 12 Top Games derived from Volumes 1-6) into new, attractively priced collections. Nr. 12, part of the main series, was a more focused product: a magazine-format disk containing one full game and two high-profile demos.

Technological Constraints & The Gaming Landscape: 1999 was a year of seismic shift. 3D acceleration (with the Voodoo2 card) and the online multiplayer boom (sparked by Half-Life’s Steam precursor and Ultima Online) defined the cutting edge. Sierra, despite publishing the revolutionary Half-Life in November 1998, was struggling to keep pace internally. Its adventure game legacy—the point-and-click SCI engine titles—was technologically obsolete against Quake and Unreal Tournament. The Best of Sierra series was a direct response to this: a low-cost, low-risk way to monetize a vast back catalog and associate the Sierra brand with current hits via demos. It catered to the nostalgia market and the undecided buyer browsing a software store shelf, offering a “taste” of Sierra’s past glory and future potential with Grand Prix Legends (Papyrus’s acclaimed 1998 sim) and the soon-to-be-legendary Half-Life.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Curating Legacy, Not Crafting Story

Best of Sierra Nr. 12 possesses no singular narrative. Its thematic depth is derived from its intentional curation, which tells a story about Sierra’s self-perception in 1999:

- The Racing Sim Pinnacle: Featuring the full version of IndyCar Racing II (1996), the compilation anchors itself in Sierra’s robust simulation lineage, a direct legacy of the Dynamix and Papyrus acquisitions. This choice highlights a genre where Sierra remained technically competitive, offering hardcore simulation as a counterpoint to the fading adventure genre.

- The “Future” Demo: The exclusive demo for Grand Prix Legends (released October 1998) is a masterstroke of marketing. It touts Sierra’s commitment to cutting-edge simulation—GPL’s physics model and historic 1967 Grand Prix season were industry benchmarks. This signals Sierra’s pivot: its future was in licensed, high-fidelity simulations, not home-grown adventure epics.

- The Blockbuster Hook: The Half-Life demo is the ultimate bait. Sierra’s publication of Valve’s masterpiece was its last great critical and commercial success. Including its demo associates the fading Sierra brand with the zenith of 1990s FPS design and the burgeoning online mod scene (Team Fortress Classic, Counter-Strike). It’s a stark reminder of what Sierra could still accomplish as a publisher, even as its development studios withered.

- The Magazine as Artifact: The “magazine” interface—with its articles, previews, and interviews from the era—is the compilation’s most poignant narrative layer. It’s a frozen moment of corporate optimism, touting upcoming releases like Gabriel Knight 3 and Homeworld (the latter a hit published by Sierra in 1999). Reading these pieces now, with the knowledge of Sierra’s imminent decline and studio closures, creates a dramatic irony. The theme is one of anxious preservation: attempting to bottle the magic of the “golden age” (KQ, SQ, LSL, QFG) while desperately pointing toward a viable future that was rapidly slipping away.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Three Experiences in One

The compilation’s gameplay is a tripartite study in contrast:

-

IndyCar Racing II (Full Game): A deep, demanding Indy car simulation from Papyrus Design Group. Its mechanics are pure 1990s hardcore racing: intricate car setup (tire pressures, wing angles, gear ratios), realistic tire wear and fuel management, and a punishing physics model that rewards finesse over aggression. The career mode and championship structure provide long-term progression. It represents the zenith of Sierra’s simulation branch—complex, uncompromising, and a world away from the point-and-click accessibility of its adventure titles. Its flaw, in a modern context, is an austere, menu-heavy interface and a sheer difficulty curve that intimidates all but the dedicated sim fan.

-

Grand Prix Legends Demo: A curated slice of what was arguably the most accurate and atmospheric racing sim ever made at the time. The demo’s mechanics focus on the visceral connection to a 1967 Lotus-Ford or Ferrari 312: a manual transmission with a физиically modelled clutch, a brutal brake-by-wire system (no ABS), and a chassis that feels alive on the historical tracks like Monza or Spa. The audio—the scream of the V8, the crackle of the gearbox—is half the game. This demo was a proof of concept for simulation realism and historical authenticity.

-

Half-Life Demo: The Opposite Extreme. The demo, likely representing the game’s opening chapter “Black Mesa Inbound,” introduced mechanics that revolutionized FPS design: a fully integrated narrative told through scripted sequences and diegetic exposition (no cutscenes), physics-based puzzles (the iconic crowbar), and a seamless, continuous world without levels. Its controls were tight, responsive, and immediately accessible. In this trio, Half-Life is the harbinger of the future; its demo is a self-contained lesson in immersive, scripted gameplay design that made Sierra’s own adventure mechanics feel archaic.

The Compilation Interface: The menu system is a functional, Windows 95-era launcher. It groups content into “Full Games,” “Game Demos,” and “Magazine,” allowing purists to boot directly into an executable or immerse in the reproduced magazine. This system is not innovative but is robust for its time, though it offers none of the modern conveniences like resolution scaling or controller support.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Museum of Eras

Best of Sierra Nr. 12 is an audio-visual palimpsest, layering the aesthetics of multiple development eras and studios:

- Visuals: The full game, IndyCar Racing II, uses textured 3D polygons for cars and tracks, with a HUD-centric, telemetry-rich interface—the look of serious simulation. The GPL demo, even in its limited content, boasts incredibly detailed, photo-scanned 3D models of 1960s cars and beautifully rendered period-accurate tracksides. The Half-Life demo presents the iconic, grimy industrial architecture of Black Mesa, with a masterful use of limited palette and real-time lighting that created unparalleled atmosphere. The magazine scans are a treasure trove of 1990s graphic design: bold headers, screenshots in “glassy” frames, and promotional art for games like King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity.

- Sound: The soundscape is equally divergent. IndyCar Racing II features engine notes, tire squeals, and spotter commentary. GPL’s audio is legendary—the visceral, analog roar of the 3.0L V8s. Half-Life’s demo introduced a generation to environmental storytelling via sound: the eerie ambient hum of the facility, the distant screams, the precise, impactful weapon sounds. The magazine includes references to Sierra’s full-motion video (FMV) ambitions (like Phantasmagoria), a technology this compilation itself does not showcase, underscoring how quickly multimedia had become a legacy element.

- Atmosphere & Contribution: The compilation’s overall atmosphere is one of robust variety and historical schizophrenia. It doesn’t create a single world but presents three: the high-stakes, technical world of professional racing; the nostalgic, tactile world of 1960s Grand Prix; and the terrifying, corporate-dystopian world of Black Mesa. Together, they argue that Sierra’s legacy was never about a single style, but about authenticity to genre. Whether simulating the slipstream of an oval or the terror of an alien invasion, the goal was immersive verisimilitude.

Reception & Legacy: The Bargain Bin as Preservation

Contemporary Reception (1999): As a budget compilation, Best of Sierra Nr. 12 likely received scant critical attention. Mainstream reviews focused on new releases. Its reception would have been defined by its value proposition: four dollars for a full racing sim and demos of two highly anticipated games. In retail, it was a meant-to-be-impulse-buy title, a way to clear old stock and introduce new franchises. Its lack of a MobyScore and zero critic reviews on the source site speak to its status as a commercial afterthought, not a critical one.

Evolving Reputation & Influence: Today, its legacy is multilayered:

1. As a Historical Document: It is a preservation tool. The included magazine provides unmediated access to Sierra’s marketing, developer interviews, and previews from a specific moment—mid-1999—when Sierra was betting on simulations (Red Baron 3-D, NASCAR Racing 3) and publishing hits (Homeworld, Half-Life) while its adventure legacy was on life support (Gabriel Knight 3 would be its last major adventure). It captures the tail end of the print-magazine-in-a-CD-ROM format Sierra pioneered with its InterAction magazine.

2. Influence on the Industry: The compilation itself had no direct mechanical influence. However, its content represents the apex of two influential lineages: the Papyrus/SimBin racing sim tree (descendant of IndyCar Racing II) and the narrative FPS tree (descendant of Half-Life). The demo function was a crucial marketing tool that built hype for these genres’ future titans.

3. The Sierra Brand’s Swan Song: Released just over a year before Sierra’s Bellevue headquarters was shuttered (June 2004) and the brand was absorbed into Activision, this issue is part of the last wave of products to bear the “Sierra” name with some semblance of its old creative authority. The subsequent 2000s saw Sierra primarily as a publisher for other studios (Relic, Radical Entertainment), a far cry from the in-house powerhouse this compilation’s back catalog represents.

Conclusion: A Definitive Verdict on a Transitional Artifact

Best of Sierra Nr. 12 is not a great game, nor was it intended to be. It is, instead, a brilliantly pragmatic and historically invaluable compilation. Its genius is in its curatorial logic: pairing a full, niche simulation with demos of titles representing the imminent future (GPL’s hyper-realism, Half-Life’s narrative FPS). It serves as a perfect microcosm of Sierra’s final business strategy: leveraging a priceless back catalog to sell a future it no longer had the internal studios to fully build.

For the historian, it is indispensable—a primary source package containing executable software, marketing ephemera, and a snapshot of corporate priorities. For the retro enthusiast, it offers immediate, authentic access to two seminal racing experiences and the landmark Half-Life demo. Its flaws are those of its era: finicky DOS/Windows 95 compatibility, absent modern features, and a conceptual structure more valuable as archive than as a coherent play experience.

Final Verdict: Best of Sierra Nr. 12 earns its place in history not for innovation, but for preservation. It is a carefully packaged bridge between Sierra’s creative golden age and its publisher’s twilight. It is a 4/5 star time capsule: essential for understanding the breadth of Sierra’s legacy and the sheer velocity of change at the close of the 20th century. To play it is to tour a museum where one wing is a 1996 racing sim garage, another is a 1967 Grand Prix paddock, and the third is the moment before a science experiment tears open a portal to another dimension—all under one crumbling, nostalgic roof.