- Release Year: 1984

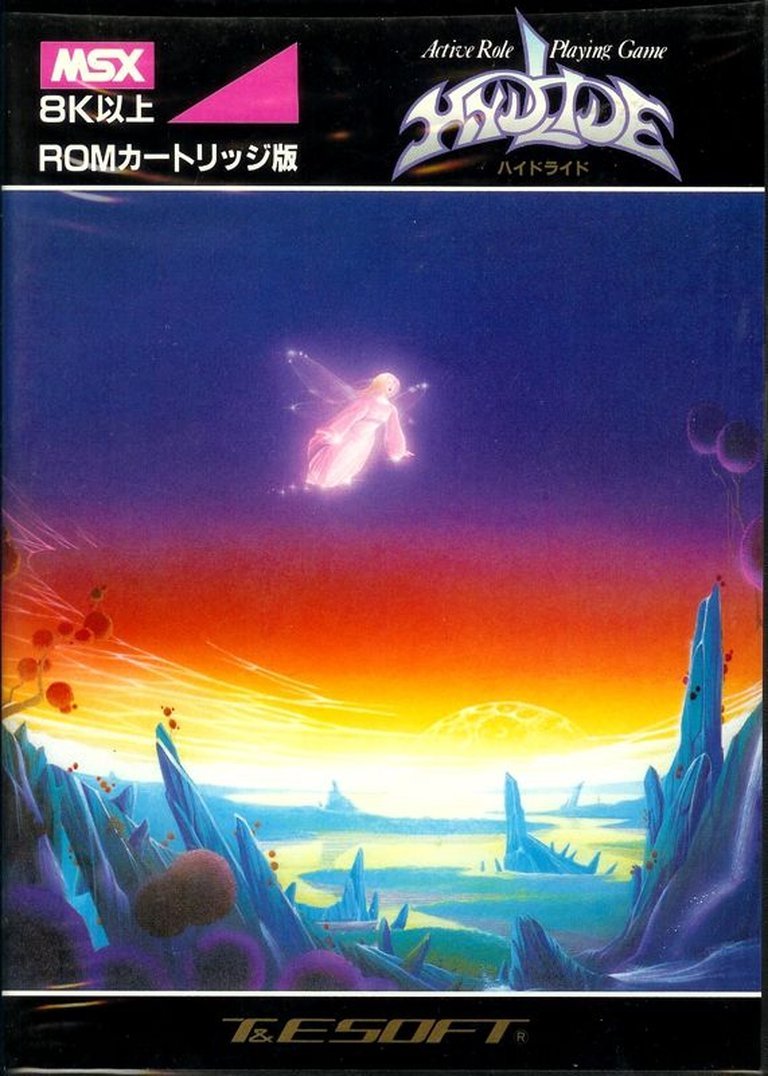

- Platforms: 2000, 2500, FM-7, MSX, NES, Nintendo Switch, PC-6001, PC-88, PC-98, PlayStation 3, PS Vita, PSP, Sharp MZ-80B, Sharp X1, Windows

- Publisher: Carry Lab, D4 Enterprise, Inc., FCI, GungHo Online Entertainment, Inc., Philips Export B.V., T&E Soft, Inc., Toshiba-EMI Ltd.

- Developer: T&E Soft, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Bump combat, Dungeon Crawling, Exploration, Leveling up, Magic, Stance Switching

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

Hydlide is an action RPG set in a fantasy world where the player controls Sir Jim on a quest to rescue Princess Ann, who has been transformed into three fairies by the evil demon Varalys. The game involves exploring vast wilderness areas and dungeons, engaging in combat by bumping into enemies (similar to the Ys series), switching between offensive and defensive stances, and using magic spells. As players progress, their character grows stronger through improved attributes, blending real-time action with role-playing elements in this classic adventure.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Hydlide

PC

Hydlide Free Download

Hydlide Patches & Updates

Hydlide Mods

Hydlide Guides & Walkthroughs

Hydlide Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (60/100): It’s tedious and finishing it can feel like a chore, but there’s a lot of satisfaction in climbing the rungs of power.

flyingomelette.com : I had no real idea what to expect when I went to play it…and was I ever in for a shock!

gamesreviews2010.com : Hydlide was a critical and commercial success upon its release, and it is still considered one of the best RPGs of its era.

Hydlide Cheats & Codes

Hydlide (NES)

Enter passwords in the in-game password menu. Enter Game Genie codes using a Game Genie device. Standard codes require a cheat device or emulator.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 798BLNR7L7BDHN75 | Access to Stage 1 |

| K2GN9PDH08MPQ580 | Access to Stage 2 |

| BH3H6PDB79PN8HM3 | Access to Stage 3 |

| 56BM5H8HM5BDHK11 | Access to Stage 4 |

| KGTLMP8DDB0KQLL6 | Access to Stage 5 |

| DDXGLKXHQ869RTG6 | Access to Stage 6 |

| 8DKKDHQ5H935R4D0 | Access to Stage 7 |

| RDVMMGV6Q7WHWDM6 | Access to Stage 8 |

| JGPMHNX8L9YGP6B5 | Access to Stage 9 |

| BGJM3VRQ88RGGL50 | Access to Stage 10 |

| H48P7BKQGRWPKN00 | Access to Stage 11 |

| XHPBJBPPB1K5KJM4 | Access to Stage 12 |

| ZBKKJKTLD9BBKLR7L | Access to Stage 13 |

| V5YMN8VJJBH52BN7 | Access to Stage 14 |

| 9BLGBPRKB9NPDR31 | Access to Stage 15 |

| PBPKKJKM68RD6VG2 | Access to Stage 16 |

| Y9VNHNLHH9XXD8RL6 | Access to Stage 17 |

| T9V8GBVQ83X9JBN5 | Access to Stage 18 |

| H4QMLBQNH7B6BN73 | Access to Stage 19 |

| RMQMLJVKV3W2PNG5 | Access to Final Stage or Fight Varalys |

| N49P89JNH2HD7M11 | Access to Level 13b |

| XBNMAMPNWQMNQHB2 | Fight Boralis |

| XBNMXMPNWQMNQHB7 | Ending Code: 90% Life, 100% Strength, 90% Magic and access to Boralis’ chamber |

| H75LBMGDN8YPWB74 | Start game with 20 Life, Cross, Pot |

| QHHL8LW59B3BLPL2 | Start outside Sword Dungeon with 20 Life, Sword, Lamp, Key, etc. |

| NKLBGJWBK7QKD653 | Start in Wasp’s Forest with 30 Life, Fairy1, Jewel, etc. |

| TNXDGJ0LD309J3Q7 | Start outside Shield Dungeon with 50 Life, Shield, etc. |

| MVTJLLM8R5WM95G3 | Start on Shore across Boralis’s Castle with 80 Life, Ring, etc. |

| KBYKQHWMWQY8R787 | Start on Shore across Boralis’s Castle with 90 Life, Everything |

| AZKAAVZE | Boost strength, life, magic |

| GTKAAVZA | Super boost strength, life, magic |

| SXSGYYSA | Don’t take damage from most monsters |

| AEUEKVIA | Rapid healing |

| AANOVZZA | Rapid magic healing |

| YYKAAVZA | Start With Full Life, Strength And Magic |

| EPPOZX | Play As Hydlide’s Head |

| PISOZT | Different Colors |

| IIIIII | Scrambled Graphics |

| PAXEYTAA | Have All Items & Have All Caves Open & Have All Events Completed |

| AEUPKUTP | Infinite Fire Magic |

| AEXXZEGL | Infinite Flash Magic |

| AAVOESAZ | Infinite Ice Magic |

| AAUOOLGP | Infinite Turn Magic |

| AEUPKTZL | Infinite Wave Magic |

| AVUKTYAZ | Invincible |

| GTGAAT | Start With Max Life, STR And Magic |

| 0038:64 | Max Health |

| 0039:64 | Max STR |

| 003A:64 | Max Experience |

| 003B:64 | Max Magic |

| 0059:FF | Start With Sword |

| 005A:FF | Start With Shield |

| 005B:FF | Start With Lamp |

| 005C:FF | Start With Cross |

| 005D:FF | Start With Pot |

| 005E:FF | Start With Medicine |

| 005F:FF | Start With Key |

| 0060:FF | Start With Ruby |

| 0061:FF | Start With Ring |

| 0062:FF | Start With Jewel |

Hydlide: The Bumpy Road to the Action RPG

Introduction: A Pioneer Buried by Its Own Rubble

In the sprawling, multi-decade narrative of video game history, few titles embody the dichotomy of pioneering innovation and crippling flaw more starkly than Hydlide. Released in Japan in December 1984 for the NEC PC-8801 and PC-6001, this game from T&E Soft arrived at the precise moment the computer RPG was blossoming. It was not merely another entry in a growing genre; it was a deliberate, audacious attempt to fuse the real-time tension of arcade action with the progression and fantasy of tabletop role-playing. The thesis of Hydlide‘s legacy, however, is a complex one: it is a foundational text for the action RPG and open-world genres, whose technical limitations, idiosyncratic design choices, and a notoriously botched Western localization conspired to bury its innovations under a landslide of frustration for a generation of players. To understand Hydlide is to witness a prototype—brilliant in concept, rough in execution—that cast a long, influential shadow despite (or perhaps because of) its notorious reputation as a “bad game.”

Development History & Context: Forging a New Path in the Japanese PC Wilderness

The Visionary and His Inspirations: Hydlide was the brainchild of Tokihiro Naito, a developer at the nascent T&E Soft. His stated goal was nothing less than to create a new genre: the “active RPG.” Crucially, Naito’s design philosophy was insular, shaped by the Japanese arcade and computer scenes rather than the Western PC RPG canon. He was deeply inspired by Namco’s The Tower of Druaga (1984), which provided the real-time, action-oriented core, and The Black Onyx (1984), which contributed the health meter and RPG progression systems. The resulting synthesis took Druaga‘s formula and applied it to a “colorful open world,” adding leveling and stats. Naito has stated he was completely unaware of seminal Western titles like Ultima or Wizardry during development, having never used an Apple II. He only discovered contemporaries like Dragon Slayer and Courageous Perseus mid-development, underestimating the former and feeling visually outclassed by the latter—a misjudgment that would have profound historical consequences as Dragon Slayer‘s sequels (most notably Sorcerian and the Dragon Slayer series itself) became the more direct ancestors of the modern ARPG.

Technological Constraints and the PC-88 Foundation: The game was built for the NEC PC-8801 (and the less powerful PC-6001), cornerstones of Japan’s “personal computer” boom. These systems had severe memory constraints (64KB for the PC-88), dictating a minimalist aesthetic. Graphics were rendered in a tile-based system with a limited 8-color palette from a fixed RGB set. Sprites were tiny 8×8 pixel entities. Most critically, the hardware could not support smooth scrolling; world transitions were abrupt “flip-screen” changes. This technical limitation fundamentally shaped the game’s pacing and sense of space, creating a disjointed, grid-based world where each screen was a self-contained arena. The sound was generated by the PC’s basic beeper, resulting in simple, repetitive chiptune melodies—a trait that would become infamous in the West.

The 1984 Landscape: In Japan, Hydlide entered a vibrant but uncrowded field. It was part of a vanguard, alongside Dragon Slayer and Courageous Perseus, defining the action RPG. The concept of a seamless, explorable fantasy world was revolutionary. In the West, however, the home computer RPG market was dominated by complex, turn-based titles like Ultima and Wizardry, while consoles were in the early days of the genre with Dragon Quest (1986) and, most significantly, The Legend of Zelda (1986). This temporal and regional disconnect would define Hydlide‘s divided reception.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Skeleton of a Fairy Tale

The plot of Hydlide is a classic, almost archetypal, fairy tale骨架, delivered with the barest of minimums. The kingdom of Fairyland is sustained by three magic jewels. An evil man steals one, breaking the seal on the demon Varalys (called Boralis in some localizations). Varalys steals the remaining jewels, transforms Princess Ann into three scattered fairies, and unleashes monsters. The silent protagonist, Sir Jim, a knight in shining armor, must gather the fairies, recover the jewels, and defeat Varalys in his castle to restore peace.

Execution and Storytelling: The narrative is not told through in-game text, dialogue, or cutscenes in the original versions. All lore, objectives, and backstory are confined to the game’s manual—a common practice in 1984 but one that creates a profound disconnect between the player’s actions and any dramatic weight. The world of Fairyland feels less like a lived-in realm and more like a series of functional obstacles (rivers, dungeons, guardians) on a path to a final boss. There are no NPCs with quests, no townspeople with stories; the “world-building” is purely environmental and mechanical.

Themes and Their Treatment: The themes are straightforward: heroism, the restoration of order, and the classic battle of good versus evil. The transformation of a princess into discrete, collectible entities introduces a faintly mechanics-first approach to storytelling—the fairies are literally power-ups that grant abilities like crossing rivers. This reduces narrative to game logic. The lack of character depth (Jim is a cipher, Ann a mac trope, Varalys a generic demon king) and absent moral ambiguity (unlike its sequels) means the game’s world has no thematic resonance beyond the most basic fairy tale conflict. It is a plot in service of gameplay, not an interactive story.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Bump, the Grind, and the Regeneration

Hydlide‘s gameplay is where its historical importance and its notorious frustrations are born, intertwined.

Core Loop and Exploration: The game presents a 5×6 grid overworld (varies slightly by port) of interconnected screens. Players traverse forests, deserts, lakes, graveyards, and castle grounds in real-time from a top-down view. The goal is non-linear in exploration but linear in ultimate progress: find three fairies (hidden in specific overworld trees or locations), obtain three treasures (Jewel, Ring, Ruby) from dungeons, and confront Varalys. Dungeons are multi-level mazes with traps, secret passages, and locked doors requiring keys found elsewhere.

The “Bump” Combat System: This is Hydlide‘s most defining and divisive mechanic. There is no attack button in the traditional sense. The player holds down a button to enter an Attack Stance, which increases damage dealt but also damage taken. Releasing the button enters Defense Stance, reducing damage taken but also dealt. To attack, the player must ram Jim into an enemy from the sides or rear while in Attack Stance. Hitting an enemy head-on as it approaches often results in mutual damage or the player’s death. This system demands positional awareness, timing, and a complete reversal of conventional combat intuition. It is a system of momentum and risk assessment, not reflexes. Critics describe it as unintuitive and “clunky,” but it introduced a real-time tactical element absent from contemporary turn-based RPGs and even from Zelda‘s simple sword swings.

Progression and Resource Management: Experience points are gained by defeating enemies, filling a progress bar that triggers automatic level-ups, increasing strength (attack power) and maximum HP. A key innovation is the Health Regeneration Mechanic. When Jim stands still outside of combat (on safe overworld tiles), his health slowly replenishes. This was revolutionary in 1984, eliminating the need for constant healing items and encouraging strategic retreats. In dungeons, regeneration is disabled unless the player finds the Lamp, a key item that also illuminates dark areas. There is no gold currency; all progression is tied to finding specific key items (Sword, Shield, Cross, Pot, Keys) in chests guarded by dungeon bosses or environmental puzzles. Inventory management is tight, forcing choices about which quest-critical items to carry.

The Grind and Its Consequences: The leveling system creates a classic “grind” loop. Early areas feature weak slimes and goblins. To survive the desert scorpions or vampire-infested graveyards, players must spend significant time battling respawning weak foes to raise their level. This padding is seen by many as a fundamental flaw—a way to extend playtime through repetition rather than content. The NES port exacerbated this with its infamous control quirks and occasional “instant death” bugs where Jim would seemingly take damage from nothing.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic Minimalism and Auditory Torment

Visual Design and Atmosphere: Hydlide‘s world is a study in minimalist, tile-based environmental storytelling. Each biome (forest, desert, lake, castle) is defined by a single background tile color and basic obstacles (trees, rocks, paths). The overworld is small by modern standards, but its lack of a minimap or clear signs made navigation a memorization task in the pre-internet era. The flip-screen transitions are jarring. Dungeons use simple wireframe-like layouts. The PC-88 original’s limited palette (8 fixed colors) creates a stark, almost abstract fairy tale landscape. The Sharp X1 port, as noted in one source, offered smooth scrolling and more organic river shapes, but purists argue this lost the “order” and clear screen boundaries that defined the original’s tactical exploration. The NES version, while color-rich, is often criticized for its bland, poorly animated sprites and tiny playfield window, making enemies hard to distinguish.

Sound Design and the Infamous Theme: The sound is Hydlide‘s most legendary (and reviled) element in the West. The overworld theme is a repetitive, high-pitched 8-bit melody that bears an uncanny resemblance to the Indiana Jones theme or “It’s a Small World After All.” It loops endlessly across every screen, in every dungeon, and even during the title screen. There is no dynamic music or context-sensitive scoring. Sound effects are crude beeps for attacks, hits, and item acquisition. For Japanese players on the PC-88’s internal speaker, this was a simple chiptune. For Western NES players in 1989, it was an inescapable auditory torment that became a central pillar of the game’s negative reputation, frequently cited in reviews and by personalities like the Angry Video Game Nerd.

Reception & Legacy: A Tale of Two Continents

Japanese Reception and Commercial Triumph: Upon its 1984 release, Hydlide was a critical and commercial darling in Japan. It was hailed as an innovator, a pioneer of the “active RPG.” Its open world and real-time combat were seen as revolutionary. It was a bestseller for two years on PC platforms. By 1990, the series had sold over 2 million copies across all platforms (1 million on home computers, 1 million on Famicom). It was the first computer game to receive a Platinum award from Toshiba EMI. It spawned a series of sequels that iterated on its formula: Hydlide II: Shine of Darkness (1985) introduced a morality meter; Hydlide 3: The Space Memories/Super Hydlide (1987/1989) added time/survival mechanics and multiple classes; and the 1995 Virtual Hydlide attempted a 3D remake for the Sega Saturn.

Western Rejection and the NES Port’s Infamy: The Western story is one of stark contrast. The MSX version had a limited European release, but the defining moment was the 1989 NES release (localized from Hydlide Special by FCI). It arrived three years after The Legend of Zelda, a game that had refined and perfected the very concepts Hydlide was clumsily exploring. Comparisons were inevitable and brutal.

Contemporary reviews were mixed-to-negative:

* Electronic Gaming Monthly gave it 22/40 (5.5/10), with one reviewer calling it “good” but another stating, “I can’t remember what this game was about. That’s how boring it is.”

* Nintendo Power rated it 2.5/5, calling its storyline “beyond what even we are used to.”

* Classic-games.net (2020): “One of the worst NES games of all time… not worth it.”

* Wizard Dojo (2017): “A convoluted bore to play today… its status as a ‘Before Zelda’ adventure title can’t save it.”

* Questicle.net gave it a rare 0%, decrying its “worthless combat system.”

The criticisms coalesced around its:

1. Jerky, headache-inducing scrolling and flip-screens.

2. Repetitive, maddening music.

3. Unintuitive “bump” combat that felt arbitrary and unfair.

4. Sparse, confusing presentation with little in-game guidance.

5. A sense that it was a rough prototype, not a finished product.

Enduring Influence and Historical Reassessment: Despite its Western infamy, Hydlide‘s influence is undeniable and documented.

* The Recharging Health Mechanic: This 1984 innovation directly inspired the similar system in Nihon Falcom’s Ys series (1987 onwards). Decades later, it became a genre staple in games from Halo: Combat Evolved (2001) to countless modern action games.

* Open-World Design: Its seamless, explorable world (within technical limits) inspired Hideo Kojima, who cited it as an influence on the open-world feel of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. Hideki Kamiya of PlatinumGames also cited the series as an influence on the cancelled Scalebound.

* Genre Foundation: Alongside Dragon Slayer and Courageous Perseus, it is considered part of the “holy trinity” that birthed the Japanese action RPG.

* Modern Rediscovery: Recent re-releases, like the 2023 Nintendo Switch port via the EGG Console service, have allowed a new generation to experience the original PC-88 version with modern save-states and translation. Critics like TouchArcade (2024, 60%) note a “compelling quality” for those who enjoy the grind, acknowledging its innovative core beneath dated presentation.

Conclusion: The Flawed Foundation Stone

Hydlide cannot be judged by the standards of polished modern ARPGs or even its contemporary Zelda. It must be assessed on its own terms: as a groundbreaking, 1984 technical prototype born on constrained hardware with a singular, radical vision. Its core mechanics—real-time bump combat, stances, health regeneration, and open exploration—were genuine innovations that rippled through gaming history. It is a game that dreamed of a world you could wander freely and fight in real-time, and in that dream, it succeeded.

However, to play the 1989 NES port today is to confront a frustrating, often unplayable artifact. Its aesthetic minimalism becomes visual poverty; its audio simplicity becomes painful repetition; its innovative combat becomes a confusing, bug-ridden mess. The gap between its ambitious design and its messy execution is cavernous.

Its place in history is therefore dual and paradoxical. On one hand, it is a seminal, must-study text for game historians, a concrete example of how hardware constraints breed creative solutions and how early concepts evolve. It laid a brick in the foundation of the action RPG and the open-world genre. On the other hand, as a playable experience for the modern audience, it is largely a historical curiosity, a game whose own flaws were magnified by an unaltered Western localization that pitted it against a masterpiece.

The verdict is inescapable: Hydlide is a profoundly important failure. It failed to capture the Western imagination at the time, and its gameplay has not aged gracefully. Yet, its DNA is in the games we love. To dismiss it solely as a “bad game” is to miss the larger story of how game genres are forged—not in pristine perfection, but in the rough, uneven, and often painful process of experimentation. Hydlide is that process made manifest: a bumpy, grindy, maddening, and utterly essential step on the road to the action RPGs and open worlds that followed.

Final Historical Verdict: Foundational but Flawed. A Pioneer whose innovations outweighed its immediate playability, cementing its status as a critical, if uncomfortable, milestone.