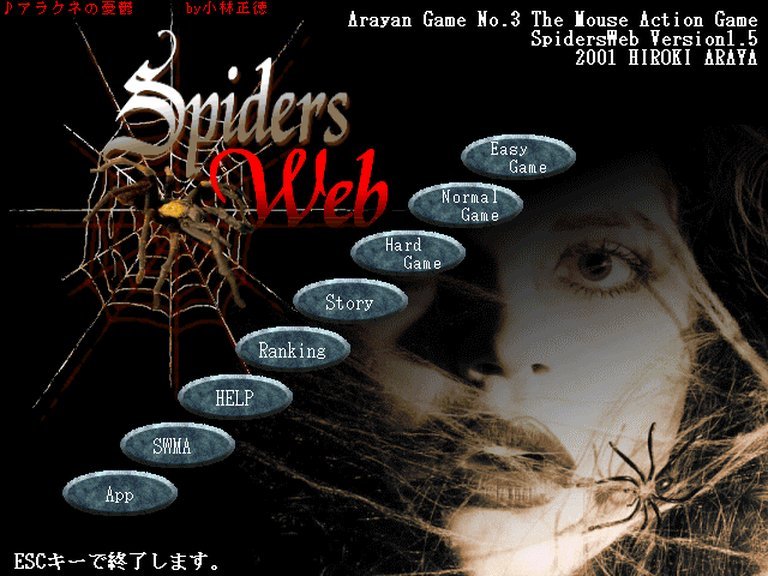

- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Shooter

Description

In Spiders Web, players control a spider from a third-person perspective at the top of the screen, shooting spiderwebs to capture insects and animals like frogs before darting down to eat them. The game progresses through areas ending with boss battles against larger creatures, and defeating bosses allows advancement. Capturing specific insects grants power-ups such as ‘machine gun web’ or ‘capture all’, with occasional bonus levels awarded after completing areas.

Spiders Web Guides & Walkthroughs

Spiders Web Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes in the SPECIAL / CHEATS menu.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| JOELSPEANUTS | Enemies Have Big Heads |

| GIRLNEXTDOOR | Play as Mary Jane |

| HERMANSCHULTZ | Play as The Shocker |

| SERUM | Play as a Scientist |

| REALHERO | Play as a Police Officer |

| CAPTAINSTACEY | Play as Captain Stacey |

| KNUCKLES | Play as Thug Model 1 |

| STICKYRICE | Play as Thug Model 2 |

| THUGRUS | Play as Thug Model 3 |

| KOALA | All Fighting Controls |

| UNDERTHEMASK | First Person View |

| ORGANICWEBBING | Infinite Webbing |

| GOESTOYOURHEAD | Big Head and Feet |

| SPIDERBYTE | Small Spider-Man |

| DODGETHIS | Matrix-Style Attacks |

| CHILLOUT | Super Coolant |

| FREAKOUT | Goblin-Style Costume |

| ARACHNID | Regular Levels,FMVs,Gallery |

| ROMITAS | Level Skip |

| IMIARMAS | Level Select |

| HEADEXPLODY | Bonus Training Levels |

| eel nats | master code |

| xclsior | level select |

| rustcrst | invincibility |

| dcstur | full health |

| strudl | unlimited webbing |

| allsixcc | all comic books |

| cviewen | all gallery characters |

| blkspider | symbiote spidey costume |

| twntyndn | spidey 2099 costume |

| FUNKYTWN | Toon Spidey |

| STICKMAN | Stick Spidey |

| CLUBNOIR | Ben Reilly Costume |

| ADMNTIUM | invulnerable |

| UATUSEES | What If Contest |

| RGSGLLRY | Character Viewer |

| CINEMA | Movie Viewer |

| FANBOY | Comic Collection |

| MME WEB | Level Select |

| KIRBYFAN | Game Comic Covers |

| ROBRTSON | Storyboard Viewer |

| SM LVIII | Quick Change Costume |

| MRWATSON | Peter Parker Costume |

| KICK ME | Amazing Bag Man Costume |

| XILRTRNS | Scarlet Spider Costume |

| SYNOPTIC | Spidey Unlimited Costume |

| TRISNTNL | Captain Universe Costume |

| MIGUELOH | spidey 2099 costume |

| SECRTWAR | symbiote spidey costume |

| RULUR | James Jewett |

| EGOTRIP | pulsating head |

| GLANDS | unlimited webbing |

| LEANEST | everything |

| WEAKNESS | full health |

PlayStation

Select the ‘Special’ option from the main menu, then choose the ‘Cheats’ selection to enter codes.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| CVIEW EM | All Characters In Gallery |

| ALLSIXCC | All Comic Books |

| WATCH EM | All Movies |

| AMZBGMAN | Amazing Bagman Costume |

| BNREILLY | Ben Reilly Costume |

| DULUX | Big Head Mode |

| S COSMIC | Captain Universe Costume |

Spider and Web: A Masterpiece of Interactive Fiction (Not to be Confused with Spiders Web)

A Note on Title and Identity: Before commencing this review, a critical clarification is necessary. The title “Spiders Web” as listed on MobyGames (Moby ID: 58625) refers to a simple, obscure 2001 freeware arcade shooter where a player controls a spider capturing insects. The provided source material, however, is overwhelmingly dominated by discussions of a seminal, award-winning work of interactive fiction titled Spider and Web (1998) by Andrew Plotkin. This review will extensively analyze that game—the one celebrated in Wikipedia, IFDB, TV Tropes, and critical discourse—as it is the only title for which sufficient, detailed source material exists. The 2001 arcade game “Spiders Web” is mentioned here solely to prevent historical conflation; it possesses no documented legacy, reviews, or mechanical depth to warrant an in-depth analysis.

1. Introduction: The Unreliable Nail

In the crowded pantheon of interactive fiction (IF), few titles achieve the sheer, cerebral audacity of Andrew Plotkin’s 1998 Spider and Web. It does not begin with a quest or a mystery, but with a lie. The player, an amnesiac “tourist,” stands in a blind alley, tasked with opening a door. Within minutes, that conceit is violently dismantled, revealing a premise so potent it redefines the player’s relationship with the narrative: you are a captured spy, strapped to a chair, being interrogated by a ruthless enemy agent. The game’s genius lies not in what you do, but in how you do it—by reliving your own mission through forced flashbacks, meticulously constructing a story that must align with the interrogator’s known facts or face lethal consequences. Spider and Web is a landmark not just for its brilliant, twist-driven plot, but for its profound deconstruction of narrative authority, player agency, and the very nature of truth in gaming. This review argues that Spider and Web stands as one of the most intellectually rigorous and mechanically innovative works of interactive fiction ever created, a piece that uses the constraints of its medium to explore themes of espionage, deception, and identity with unmatched elegance.

2. Development History & Context: The Zarf Engine

The Creator & The Scene: Andrew Plotkin, known in the IF community by his handle “Zarf,” was already a respected figure by 1998, having released acclaimed works like So Far (1996) and Shade (1998). He operated at the tail end of the great “IF Renaissance” of the 1990s, a period fueled by the freeware distribution of Inform (the compiler) and the Z-machine (the virtual runtime). This community was intensely creative, producing hundreds of games annually, with the XYZZY Awards serving as its primary honors. Plotkin’s work was distinguished by meticulous prose, parser finesse, and conceptual daring.

Technological & Design Context: Spider and Web was built using Inform 6, targeting the Z-machine. This placed it within a tradition of parser-based, text-only adventures dating back to Infocom. However, Plotkin used these “limitations” as a canvas for innovation. The game’s core mechanic—the interrogation/reliving structure—required a parser that could understand a vast array of actions while remaining silent on the “true” narrative, saving its commentary for the interrogator’s interventions. This demanded exceptional programming discipline. The game was self-published as freeware, disseminated via Plotkin’s website and the IF Archive, embodying the non-commercial, community-driven ethos of the era.

Aesthetic Predecessors: Thematically, it fits within a wave of mid-to-late-90s IF that embraced psychological and philosophical complexity (Photopia, Slouching Towards Bedlam). Structurally, it shares DNA with “interrogation” narratives (e.g., the film The Interview) but subverts them by making the player’s own actions the subject of scrutiny. Its release in 1998 placed it just before the widespread adoption of graphical adventure games and the nascent rise of indie gaming, making it one of the final great masterpieces of the pure text adventure form.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Layers of Deception

The Framing Device & Unreliable Narrator: The entire plot is a framing device. The protagonist (never named, genderless) is a spy captured while infiltrating a totalitarian state. The antagonist is “The Man,” the interrogator, whose personality—cultured, patient, but utterly ruthless—is revealed through his office’s details (books, sketches) and his restrained, analytical dialogue. The player’s primary goal is to survive by recounting the events of the infiltration in a way that does not contradict the physical evidence The Man possesses (e.g., a broken lockpick, a missing package).

Plot Structure & The “Wham Line”: The narrative unfolds in three clear phases:

1. The Cover Story: The initial forced “tourist” flashback, where the player blindly attempts mundane actions (opening doors, looking at sights) only to be interrupted and corrected by The Man. This phase teaches the core mechanic: The Man knows more than you, the player, do.

2. The Spy Story: After a pivotal event—the discovery and use of a hidden device called “Tango” (the “Wham Line” / “Wham Episode”)—the perspective shifts. The player now understands they are the spy, using gadgets to complete a mission. The flashbacks become coherent, and the challenge transforms into avoiding contradictions about how the mission was executed.

3. The Resolution: The endgame involves retrieving the Package (plans for a teleporter) and making a final choice: deliver it, destroy it, or steal it. The nature of the “Package” is a masterful Chekhov’s Gun subversion—it was a lie the spy told to hide his real tool (the gun), making its eventual reality a payoff to the player’s own deception.

Core Themes:

* Truth as Performance: The spy’s life depends on constructing a plausible fiction that aligns with evidence. The game becomes a meta-commentary on storytelling itself—the player is both author and character, editing their own past to satisfy an external editor (The Man).

* The Banality of Evil & The Mirror of Conflict: The Man is not a cartoon villain. He’s intelligent, philosophical, and at one point states, “…we are faces reflected in the mirror of our countries’ border. I think you understand that.” This “Not So Different” Remark forces the player to consider the moral symmetry of espionage.

* Agency & Constraint: True agency is not about freedom, but about navigating a labyrinth of predetermined truths. The most powerful moment is not a physical victory, but the intellectual one where the player outsmarts The Man by finally understanding the real sequence of events.

* Cold War Paranoia & Applied Phlebotinum: The setting is a “Space Cold War” with two moons (linking it to Plotkin’s So Far). The spy’s gadgets—pulse guns, scramblers, teleporters—are treated as mundane tools, creating a sense of grounded, high-tech intrigue.

Dialogue & Character: All “dialogue” with The Man is reduced to binary “yes” or “no” responses, a brilliant minimalist choice that focuses tension on what the player chooses to affirm or deny. The Man is the game’s Best Individual NPC (XYZZY Award winner), a character whose menace is conveyed through what he doesn’t say, his pauses, and his matter-of-fact descriptions of your impending “execution” for lies.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Logic of Interrogation

Core Loop: The game is divided into interrogation sessions. Each session corresponds to a segment of the mission. The player is “placed” in a location via flashback and must perform the actions the spy actually took, which are constrained by the facts The Man already knows.

* The Constraint Mechanic: If an action contradicts evidence (e.g., opening a door that should have triggered an alarm), The Man interrupts, explains the contradiction, “executes” the player (game over), and resets the flashback. The player must then deduce the correct prerequisite action (e.g., “I need to shut off the alarms first”).

* The Puzzle as Revelation: The primary “puzzles” are not inventory-based, but narrative-based. The challenge is inferring the true chronology. As one IFDB review notes, this is often a process of “trial and error” where the interrogator’s corrections are cryptic clues. This creates a unique, frustrating-but-rewarding cognitive loop: Hypothesis → Contradiction → Deduction → Reformation.

Innovative Systems:

1. Dynamic Parser Knowledge: The parser understands actions relevant to the spy’s toolkit (using gadgets, climbing, sneaking) but will reject actions that break cover (e.g., trying to “examine guard” might get “You don’t have time for that in your story”).

2. Inventory as MacGuffin & Red Herring: The “wrapped package” is a central Red Herring. The player is told to acquire it, but for most of the game, attempts to open it are met with “Not yet.” This brilliantly maintains mystery—is it the teleporter plans? The game’s ultimate twist reveals the package was never real, a lie to hide the gun.

3. The “Escape from the Chair” Puzzle: Winner of the Best Individual Puzzle XYZZY Award. Early in the game, the player must physically escape the interrogation chair using items on their person. This puzzle is so well-integrated that many players don’t realize it’s a puzzle at all until they solve it, making it a perfect “Deconstruction Game” moment—you realize you’ve been playing along with a physical constraint you were meant to accept.

4. Unwinnable by Design? The game can become unwinnable if the player makes certain irreversible choices in the flashbacks without key items. However, this is often framed as a narrative dead end—The Man simply notes you’ve contradicted yourself fatally. It’s a harsh but thematically consistent design.

Flaws: The trial-and-error nature can lead to “fumbling” (per a IFDB review), especially in the late game when The Man’s guidance becomes sparser for plot reasons. The final puzzle to secure the teleporter plans requires significant “reading between the lines,” and some players have noted the endgame’s thematic weight slightly misfires, leading to a “whimper of a conclusion” for some, despite the profound choices presented.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Power of Suggestion

As a text-based work, Spider and Web’s “art” is purely descriptive, but its world-building is exceptionally potent.

* Setting & Atmosphere: The world is sketched with minimal, precise strokes. The interrogator’s office reveals a cultured, oppressive state. The flashback locations—the “ethnic” streets, the “historic” capital, the “Old Tree”—are presented through the spy’s utilitarian perspective, making their eventual sinister undertones more chilling. The “Alien Sky” (two moons) is a single, loaded detail that implies a shared universe with So Far and vast, strange history.

* Visual Direction (In Text): Plotkin’s prose is “excellent” (universally noted in reviews). Descriptions are economical but evocative. A guard’s uniform, the feel of a lockpick, the sterile hum of a lab—each detail is chosen to build tension and characterize the world’s technological parity and political tension.

* Sound Design (In Text): In pure IF, sound is implied. The “pulse gun” firing “a corona of sparks” on inanimate objects, the “click” of a lock, The Man’s calm, interruptive voice—these are auditory anchors in the player’s imagination. The lack of actual sound forces the reader to construct the atmosphere mentally, a process that deeply invests them in the scenario.

* Contribution to Experience: This minimalist approach is essential. Any graphical representation would likely flatten the ambiguity. The player’s imagination fills the gaps, making the world feel larger and the consequences more personal. The “severe aesthetic asceticism” (to borrow a term from the Spiderweb Software discussion, though that refers to graphics) here applies to text: every word must earn its place, and they all do.

6. Reception & Legacy: From Cult Classic to Canon

Contemporary Reception (1998): Spider and Web was a phenomenon in the small IF world. It won five XYZZY Awards in 1998, including the prestigious Best Game, and was a finalist for four more (Best Story, Best Writing, etc.). This sweep signaled immediate, widespread critical acclaim from peers and reviewers. As one awards listing shows, it won Best Use of Medium, a crucial nod to its innovative structure.

Long-Term Reputation: Its stature has only grown.

* IFDB & Community Veneration: With 328 ratings on IFDB maintaining a stellar average (effectively 4.5/5 from 328 weighted ratings), and 19 member reviews lavishing praise, it’s considered a foundational classic. It consistently places in the Top 10 of the Interactive Fiction Top 50 polls (1st in 2011, 2nd in 2015, 4th in 2019, 3rd in 2023).

* Mainstream Recognition: PC Gamer included it in their “Top 100 Greatest Games” list in 2015, a stunning acknowledgment from a non-IF-centric publication. They called it “an oldie but a goodie, this spy story is one of the most enjoyable examples of unreliable narration, and a story that couldn’t be told any other way.”

* Critical Consensus: Reviews from Baf’s Guide, Adventure Gamers, SPAG, and others uniformly praise its “sheer genius in terms of premise and construction,” its “brilliance” in framing, and its status as a “real gem.” A common note is the initially steep, trial-and-error difficulty, but the payoff is described as immense—one reviewer on IFDB stated they were “awestruck” within ten minutes.

Influence on the Industry & Genre:

* Interactive Fiction: Spider and Web established the “interrogation flashback” as a viable, profound narrative structure for IF. It demonstrated how to use a limited interface (yes/no) to create immense dramatic tension. Its success influenced later Plotkin works and countless IF authors exploring unreliable narrators and meta-commentary.

* Broader Gaming: Its themes and structure can be seen as a precursor to later narrative-heavy games that play with player knowledge vs. character knowledge, such as Her Story (2015) or even The Stanley Parable (2013). It proved that a game could be about the construction of a story, not just the experiencing of one.

* Academic Study: The game is frequently cited in academic papers on narrative in games, ludology, and interactive storytelling, with its “Deconstruction Game” nature a key subject of analysis. Its source code was released by Plotkin in 2014 for educational purposes, cementing its status as a study text.

Why It Endures: It is not a game about flashy combat or vast worlds. It is a “thinking player’s game” that respects the player’s intelligence. Its themes of truth, propaganda, and the stories we tell to survive remain perennially relevant. As one IFDB reviewer poignantly noted, it’s a game that “forces the player not only to accept someone else’s account of a certain truth… but to replay them in conformity with what he’s told—and the feeling is often unnerving.” That unnerving, cerebral engagement is its lasting legacy.

7. Conclusion: The Verdict and the Legacy

Spider and Web is not merely a great interactive fiction game; it is a definitive masterpiece of the form. Its brief, freeware existence belies a depth and ambition that rivals the works of Infocom’s golden age. By making the player complicit in the construction of a lie to survive, it achieves a level of narrative integration few games have matched. The mechanics are perfectly married to theme: every parser error, every correction from The Man, reinforces the core premise of interrogation and self-editing.

Its flaws are minor and often inherent to its design philosophy—the trial-and-error can frustrate, the open-ended finale can feel unsatisfying to those wanting explicit closure. Yet these are also its strengths, mirroring the confusion and moral ambiguity of espionage itself.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, Spider and Web occupies a unique niche. It is a pinnacle of textual interactive storytelling, a bridge between the literary ambitions of early IF and the narrative experimentation of modern indie games. It proves that profound experiences can be built with nothing but words, a parser, and a brilliant, uncompromising vision. While a different, forgettable 2001 arcade game shares a similar name, Andrew Plotkin’s Spider and Web is the true titan—a “landmark” status work (to quote an IFDB reviewer) that remains, decades later, a “yardstick by which all others are measured” in the realm of narrative innovation.

Final Verdict: 5/5 Stars. An essential, timeless experience for anyone interested in the art of interactive storytelling. Seek it out, play it with patience, and prepare to have your understanding of what a game can be—and what you, as a player, are actually doing—irreparably altered.