- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: eGames, Inc.

- Developer: Zillions Development Corporation

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Board game, Chess

- Setting: Chess board

Description

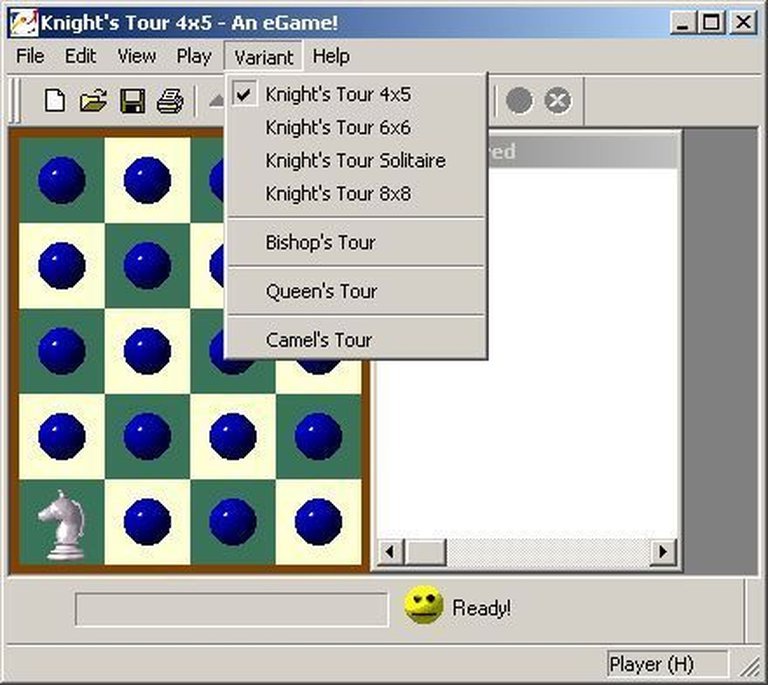

Knight’s Tour is a puzzle game developed by Zillions Development Corporation, featuring a collection of seven chess-based challenges on mini boards of varying sizes. Players maneuver a single chess piece—including knights, a bishop, a queen, or a fictional camel—to solve objectives such as covering every square exactly once with a knight or clearing the board of other pieces in minimal moves, with all solutions provided.

Knight’s Tour Free Download

Knight’s Tour Guides & Walkthroughs

Knight’s Tour: A Digital Reliquary for a Millennium-Old Enigma

Introduction: The Knight’s Labyrinth

To encounter Knight’s Tour (2001) is to open a beautifully carved, yet utterly silent, reliquary. It is not a game of sprawling narratives, cinematic set-pieces, or adaptive AI. Instead, it is a pure, distilled artifact—a digital vessel for one of humanity’s oldest and most beguiling intellectual puzzles. Developed by the prolific but low-profile Zillions Development Corporation and published by eGames, this title’s legacy is not one of commercial blockbuster status or mainstream critical acclaim; its score on MobyGames remains “n/a,” collected by a mere two players. Its true significance lies elsewhere: in its role as a accessible, packaged preservation of a mathematical problem that has captivated poets, mathematicians, and mystics for over a millennium. This review argues that Knight’s Tour is a vital, if minimalist, historical document. It succeeds not through innovation in game design, but through faithful and elegant curation, transforming an abstract graph theory problem into a tactile, solitaire experience that connects the player directly to a continuum of intellectual pursuit stretching from 9th-century Sanskrit scholars to modern computer scientists.

Development History & Context: The Zillions of Games Ecosystem

Knight’s Tour did not emerge into a vacuum; it was a single element within a vast, meticulously assembled ecosystem. The developer, Zillions Development Corporation, was not a household name but a specialist studio synonymous with one core product: Zillions of Games. At version 2.0, this package contained 375 distinct games. The philosophy was clear: build a universal game-playing engine capable of rendering any abstract board or puzzle game via rule-based definitions. Knight’s Tour was one of these definitions—a ruleset specifying a board, a piece (or pieces), and a win condition—plugged into this generic, highly modular framework.

The studio’s vision, led by Concept & Language lead Jeff Mallett and Designer Mark Lefler, was one of exhaustive, encyclopedic completeness rather than artistic auteurism. The technological constraints of the era (Windows 98/2000) favored this approach; a single, robust engine could host hundreds of games without the resource drain of individual development. The gaming landscape of 2001 was dominated by 3D accelerations and online multiplayer, making Knight’s Tour a deliberate niche product. It belonged to the “casual puzzle” and “budget compilation” segment, often sold alongside other eGames titles or as part of collections like Greenstreet’s Board Games (2003). Its context is not The Legend of Zelda or Grand Theft Auto III, but the quiet, enduring tradition of boxed puzzle collections and the early 2000s “casual gaming” boom that valued intellectual engagement over sensory spectacle. The game is a testament to the PC’s power as a universal game board.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Problem as Protagonist

Knight’s Tour possesses no traditional narrative. There are no characters, no dialogue, no plotted conflict. Yet, it is imbued with a profound and deep narrative—the story of the problem itself. The game’s thematic core is the centuries-old quest to find a knight’s tour: a sequence of moves on a chessboard where a knight visits every square exactly once. This is the “plot.”

The history of this problem, detailed extensively in the Wikipedia source, becomes the game’s lore. The player is implicitly engaging with:

* ThePoetic Tradition: The 9th-century Sanskrit Kavyalankara of Rudrata and the 14th-century Paduka Sahasram of Vedanta Desika, where the tour was a citra-alaṅkāra (visual figure of speech), a mnemonic device encoded in verse. The player’s cursor becomes the poet’s stylus, tracing meaning through space.

* The Mathematical Tradition: The formalization by Euler in 1759, the development of Warnsdorf’s heuristic in 1823, and the modern computational proofs by Schwenk, Cull, and Conrad. The player’s struggle to find a path is a hands-on experience of the Hamiltonian path problem.

* The Cultural Mystique: Its appearance in Oulipo literature (Perec’s Life a User’s Manual), its rumored use in the Rennes-le-Château mystery decoding, and its symbolic interpretation as a masonic allegory or a representation of the golden ratio (√5 from the knight’s 1-and-2 move). The “Camel’s Tour” puzzle, featuring a fictitious piece, extends this tradition into speculative game design.

The game’s underlying theme is constrained exploration and universal visitation. The knight’s unique, non-linear movement (an “L” shape: two squares in one direction, one perpendicular) creates a disjointed, leaping traversal. The puzzle asks: Can this discontinuous motion achieve a continuous, all-encompassing coverage? This metaphor extends beyond the board—it speaks to systems thinking, to finding a path that touches all elements of a complex whole without repetition. The minimalist presentation forces the player to focus entirely on this spatial-logical narrative.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegance of Constraint

Knight’s Tour is a masterclass in focused, rule-based design. Its mechanics are Spartan but deeply systemic.

Core Gameplay Loop:

1. Selection: The player selects one of seven puzzles from a simple menu.

2. Observation: A small, top-down, fixed/flip-screen chessboard appears, populated according to the puzzle type (e.g., an empty 5×5 board for a “Knight’s Tour,” or a board with several enemy pieces for the “Bishop Clear” puzzle).

3. Execution: Using the mouse (the only supported input), the player clicks a legal move for the active piece. The move is animated simply (the piece relocates).

4. Evaluation: The game provides immediate, binary feedback. For the four Knight’s Tour puzzles, success is filling every square exactly once. For the Bishop, Queen, and Camel puzzles, success is “clearing the board” (capturing all other pieces) in the fewest possible moves. Solutions are provided for all puzzles, a crucial inclusion that transforms the game from a pure challenge into a learnable system.

Deconstructed Systems:

* The Knight’s Tour Puzzles: These are pure Hamiltonian path problems on varying board sizes (likely standard chessboard subsets and smaller). The challenge is cognitive mapping and planning several moves ahead to avoid isolating unvisited squares (creating “unreachable” islands). The simplicity of the piece’s movement rule generates immense combinatorial complexity.

* The Piece-Clearing Puzzles (Bishop, Queen, Camel): These introduce a minimalist combat/progression system. The objective shifts from visitation to efficient capture. The bishop (diagonal-only) and queen (any direction) must strategize to minimize moves, introducing a layer of optimization metrics (move count) atop the traversal puzzle. The “Camel” (a fictional piece moving 3+1 squares) is a fascinating variant, demonstrating the developers’ understanding that the core fun lies in exploring the rule-space of “knight-like” movement.

* Progression & UI: There is no character progression, no skill trees, no economy. Progression is purely puzzle-to-puzzle. The UI is a triumph of clarity: the board, the piece, and (implicitly) the set of visited squares. The “point and select” interface is perfect—no timing, no dexterity required, only decision-making. The primary “innovative” system is the bundled solution guide. This is not a hint system, but a post-hoc validation and learning tool. It allows for a “productive failure” loop: struggle, give up, study the solution, and internalize the patterns (like Warnsdorf’s rule, where one moves to the square with the fewest onward exits). This makes the game an educational tool for graph theory heuristics.

* Flaws: The package is static. There is no procedural puzzle generation (a notable absence, given the astronomical number of possible tours), no difficulty slider beyond board selection, and no meta-game or unlockables. For a modern audience, the lack of a dynamic puzzle generator for infinite replayability is its greatest limitation. It is a curated museum exhibit, not an endlessly scalable engine.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Notation

The world of Knight’s Tour is the board itself. There is no diegetic setting—no fantasy realm, no abstract space. The “atmosphere” is one of solitary, cerebral focus.

- Visual Direction: The “top-down, fixed/flip-screen” perspective presents the board as a diagram. The art, credited to a team including Colin Gerbode and Brenda Mallett, is functional and clean. Likely utilizing simple 2D sprite graphics common for early-2000s casual titles, the visual language is that of a digital chess set. The squares are clearly demarcated; the pieces are recognizable icons. This aesthetic reinforces the game’s nature as a problem to be solved, not a world to be immersed in. The “world” is the mathematical space of the grid.

- Sound Design: Based on its genre and era, sound was likely minimal: perhaps a simple click for movement, a chime for completion, and silence otherwise. Any ambient track would have been optional or absent. The soundscape would be designed to not distract from the core cognitive task. The dominant sensory input is visual-spatial.

- Contribution to Experience: This stripped-down approach is essential. By removing narrative dressing, atmospheric music, and visual “juice,” Knight’s Tour achieves a state of pure ludic reduction. The experience is not about feeling like a knight; it is about thinking with the knight’s movement graph. The aesthetics serve to eliminate all stimuli except the essential puzzle. This makes it a unique form of digital meditation—a “zen puzzle” where the only tension is the logical gap between current state and solved state.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Influencer

Knight’s Tour (2001) existed in a commercial blind spot. It received no mainstream critic reviews (as evidenced by the empty MobyGames review page and lack of Metacritic entry). Its “reception” was confined to the niche audience for Zillions of Games—puzzle enthusiasts, educators, and casual PC gamers buying bargain bins. Its commercial success is undocumented, but its inclusion in later compilations like Board Games (2003) suggests a modest, steady life.

Its true legacy and influence are indirect and academic:

1. Preservation & Accessibility: It served as a digitization of a classical problem. Before ubiquitous online solvers, having a playable, validated version of the Knight’s Tour on a home PC was a convenience for students and hobbyists. It made the abstract concrete.

2. Pedagogical Tool: The package’s clear rules and built-in solutions made it a quiet staple in computer science and mathematics education for demonstrating Hamiltonian paths, backtracking algorithms, and heuristics like Warnsdorf’s rule. It exists in the same lineage as the “Hello World” program or the “Towers of Hanoi” applet.

3. Genealogy of the “Puzzle Game” Genre: It represents a specific sub-strand: the single-rule, high-depth puzzle. This lineage includes Minesweeper, Lemmings (in its puzzle form), and later, mobile titles like Bloxorz. Knight’s Tour prioritizes a single, elegant mechanic whose depth emerges from the initial conditions (board size, piece rules). It is an anti-“game feel” game, prioritizing logic over kinetics.

4. Cultural Echoes vs. Direct Influence: While the concept of the knight’s tour influenced literature (Perec), art (garden mazes), and even esoteric codes (Rennes-le-Château), this specific 2001 implementation had little direct impact on the broader industry. It did not spawn clones or redefine genres. Its influence is in its existence as a perfect, portable format for the problem, a reference implementation that any curious programmer or mathematician could load and explore.

Its reputation has evolved from obscurity to quaint historical artifact. In an era of mobile puzzle giants like Monument Valley or The Witness, it is seen as a relic—but a pure one. It is appreciated as a counterpoint to modern puzzle design’s emphasis on presentation and gradual onboarding. Here, the onboarding is the puzzle’s history; the