- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

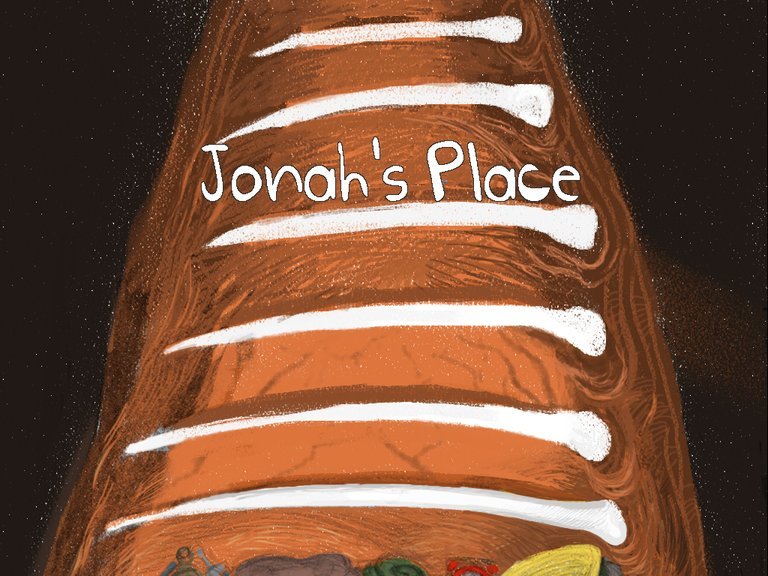

Jonah’s Place is a free 2D point-and-click adventure game where players control a young girl who, after being swallowed by a large fish, awakens in the surreal one-room dwelling of Jonah—an eccentric old sailor surrounded by talking animal heads. The game features meditative pacing, fixed-screen visuals, and puzzle-solving elements as the protagonist navigates this bizarre fantasy setting to find an escape, using only mouse-driven point-and-click interactions to progress through its unique detective-style narrative.

Jonah’s Place Free Download

Jonah’s Place: Review

Introduction

In the vast landscape of video games, few titles dare to embrace radical minimalism. Jonah’s Place, a freeware adventure released in 2012, stands as a defiant outlier—a one-room odyssey distilled to its surreal essence. As a point-and-click adventure born from the MAGS competition’s “The Pub” theme, it defies conventional design by confining players to a single, enigmatic space. This review examines how Jonah’s Place leverages constraint to craft a dreamlike puzzle-box experience, arguing it succeeds as a conceptual experiment despite its technical and narrative shortcomings. Its legacy lies not in polish, but in its fearless exploration of interactive surrealism.

Development History & Context

Kasander and ddq developed Jonah’s Place using the Adventure Game Studio (AGS) engine, a tool democratizing 2D adventure creation. Created for the January 2012 MAGS contest—prompted by the theme “The Pub”—the game subverts expectations by relocating the “pub” to a sailor’s den. Kasander handled art and screenplay, while ddq managed coding, a division reflecting the game’s duality: painterly visuals paired with functional, minimalist mechanics. Released on September 5, 2012, as freeware, it emerged amid the indie boom of the early 2010s, where titles like Minecraft and Limbo celebrated boundary-pushing design. Yet Jonah’s Place occupies a niche: a micro-budget, MAGS-entrant project prioritizing atmosphere over scale. Its one-room concept was both a creative constraint and a deliberate statement against industry trends of sprawling worlds, aligning with the “meditative/zen” pacing specified in its technical specs.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative unfolds with absurdist brevity: a little girl falls into a fish’s belly, is transported to Jonah’s place, and must escape. The plot serves as a surreal framework for existential themes—displacement, the uncanny, and the fragility of identity. Jonah, an old sailor, never appears directly; his presence is inferred through taxidermied animal heads that mock the girl’s attempts at escape. These heads—voiced with dark humor—act as antagonistic guides, their dialogue a mix of nonsense and cryptic warnings: “Beware the tides of change, little one.”

The story operates on dream logic, evoking Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland or Lynchian surrealism. The girl’s journey mirrors a psychological purgatory: the fish’s belly as a womb, Jonah’s room as a liminal space. Thematic weight emerges through environmental storytelling—peeling posters, a broken compass—implying a lost maritime civilization. Yet the narrative’s ambiguity frustrates; without exposition, players must intuit meaning from visual cues alone. This abstraction aligns with the game’s “detective/mystery” genre tag, though the investigation is less about clues and more about interpreting a coded, subjective reality.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Kasander and ddq reduce adventure gaming to its core: observation and interaction. Gameplay is a loop of point-and-click exploration and inventory-based puzzles. The mouse-driven interface is clean but rudimentary, lacking AGS’s more advanced features. Puzzles center on environmental manipulation—aligning symbols, feeding fish bones to a head—but suffer from ambiguity. As one critic noted, “puzzles were too weird… pixel hunting turned me off.”

The game’s signature mechanic is the “glowing animation,” where objects pulse with ethereal light, hinting at interactions. These moments—described as “very Van Gogh”—create moments of clarity amid the surrealism. Yet technical flaws undermine immersion: reported glitches (e.g., unresponsive hotspots) and a poorly timed “quicktime event” break pacing. Inventory management is straightforward but underutilized; items serve only as keys, lacking the multi-layered puzzles of classics like Monkey Island. The absence of combat or progression systems reinforces the game’s meditative intent, but also limits engagement beyond curiosity.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Jonah’s room is a masterclass in claustrophobic design. The 800×600 canvas is filled with decaying nautical artifacts: nets, anchors, and mounted animal heads whose eyes follow the player. Kasander’s hand-drawn art blends realism with caricature, the heads rendered with grotesque expressiveness. Textures—peeling paint, splintered wood—create tactile unease, though a user noted graphics were “less shiny than the spiced up speech lines.”

Color palettes shift from warm sepias (entrance) to cold blues (exit), symbolizing the girl’s emotional journey. Sound design is sparse but effective: the creak of a door, distant seagulls, and a piano-driven soundtrack that avoids thematic overreach. As the AGS review observed, the music “relaxes your mind” but feels detached from the setting, a choice that reinforces the dreamlike unreality. The room itself is a character—its labyrinthine clutter hiding secrets in plain sight, rewarding meticulous observation. This micro-world, confined yet infinitely detailed, exemplifies how art can compensate for narrative brevity.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Jonah’s Place garnered muted attention. MobyGames lists no critic reviews, and player feedback on AGS forums is polarized. One user dismissed it as “glitchy and unattached,” while Kasander defended it as a “one-room MAGS game, made in couple of days.” The AGS review praised its “association of ideas” and glowing animations but critiqued its “inappropriate” humor and tonal disjointedness. Its legacy is modest: it spawned imitators like Purple Place (2023) and Fire Place (2018), forming a loose “Place” series. Yet it remains a footnote, overshadowed by contemporaries like Journey (2012)—which, coincidentally, explores similar themes of liminal spaces and wordless storytelling but with far greater polish. Jonah’s Place endures as a cult curiosity, preserved by the Internet Archive, admired for its audacity more than its execution.

Conclusion

Jonah’s Place is a paradox: a technically flawed, narratively opaque game that achieves a singular artistic vision. Its one-room design is both a limitation and a strength, forcing players into intimate engagement with its surreal ecosystem. Kasander’s art and the AGS engine’s flexibility create a haunting, self-contained world, while the talking heads inject dark humor into its existential undertones. Yet the game’s brevity, ambiguity, and technical issues prevent it from transcending its niche.

In the annals of video game history, Jonah’s Place is a fascinating artifact—a testament to the power of constraint in a medium obsessed with scale. It may not be a masterpiece, but it is a compelling experiment, proving that adventure games need not sprawl to be profound. For those willing to embrace its weirdness, it offers a brief, luminous dive into the uncanny—a place worth visiting, if only to remember how strange a single room can be.