- Release Year: 1993

- Platforms: DOS, Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: 3D Realms Entertainment, Inc., Apogee Software, Ltd., FormGen, Inc., Red Sprite Studios, WizardWorks Group, Inc.

- Developer: Interactive Binary Illusions, SubZero Software

- Genre: Action, Horror

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Jetpack, Platform, Shooter

- Setting: 2030s, Space station, Spaceship, Zombie

- Average Score: 83/100

Description

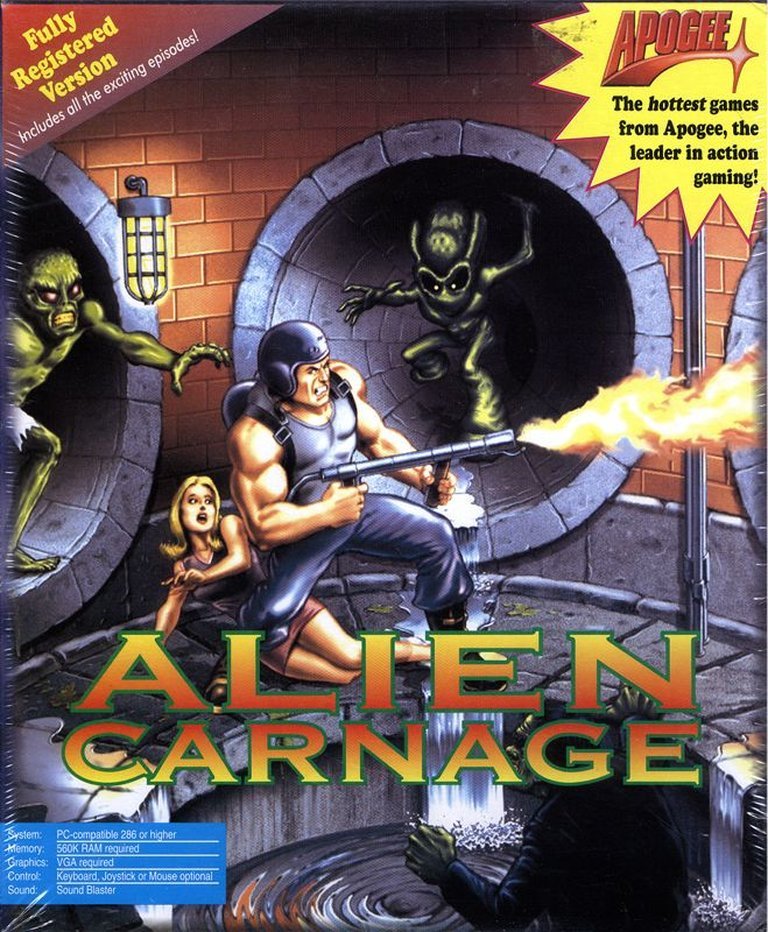

Set in the year 2030, Alien Carnage (also known as Halloween Harry) is a side-scrolling platform shooter where Earth faces invasion by hostile aliens who transform humans into zombies to enslave the planet. As the lone hero Harry, players must navigate through diverse levels including office buildings, factories, sewers, and an alien spaceship, rescuing hostages, battling zombie hordes and bosses, and utilizing a flamethrower-equipped jetpack along with an arsenal of limited-ammo weapons like missiles and nukes to thwart the extraterrestrial threat and save humanity.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Get Alien Carnage

DOS

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (89/100): It featured jaw-dropping VGA graphics and digital music consisting of MOD files.

gamepressure.com (85/100): Pleasant graphics, realized in cartoon style and quite good soundtrack.

myabandonware.com (92/100): It was moderate and in some cases very innovative.

Alien Carnage: Review

Introduction

In the neon-drenched underbelly of 1990s PC gaming, where shareware demos zipped across dial-up modems and Apogee Software reigned as the king of bite-sized action epics, Alien Carnage emerges as a fiery blast from the past—a side-scrolling shooter that torches zombies with gleeful abandon while rescuing hapless civilians from an extraterrestrial nightmare. Originally released as Halloween Harry in 1993, this game marked a pivotal evolution for publisher Apogee, transitioning from EGA’s blocky charm to the lush 256-color splendor of VGA, all while embodying the era’s unapologetic blend of horror, heroism, and high-octane platforming. As a professional game journalist and historian, I’ve revisited countless relics of the DOS golden age, but Alien Carnage stands out for its unpretentious joy: it’s a love letter to the lone gunslinger archetype, wrapped in alien slime and flamethrower fuel. My thesis is simple yet profound: while it doesn’t reinvent the platformer wheel, Alien Carnage exemplifies Apogee’s mastery of accessible, addictive design, cementing its legacy as an underappreciated gem that bridges the gap between arcade thrills and narrative-driven action, deserving a spot in any retro enthusiast’s hall of fame.

Development History & Context

The story of Alien Carnage begins in the sun-baked suburbs of Australia, far from the silicon valleys of Silicon Valley. Developed by Interactive Binary Illusions (later rebranded as Gee-Whiz Entertainment) and SubZero Software, the game was spearheaded by a talented core team including designer John Passfield, writer Robert Crane, and artist Steven Stamatiadis. Passfield, in particular, brings a personal touch: he had previously created an eponymous Halloween Harry in 1985 for the obscure Microbee computer, a rudimentary platformer that captured his early fascination with haunted-house antics. By 1993, however, Passfield and his collaborators had leveled up, aiming to craft a spiritual successor that ditched the seasonal Halloween gimmick for broader appeal.

Apogee Software, the pioneering Texas-based publisher, scooped up the project, recognizing its fit within their shareware empire. Founded by Scott Miller, Apogee revolutionized distribution in the early ’90s by releasing free first episodes to hook players, who then paid for the full game via mail-order. This model fueled hits like Duke Nukem and Commander Keen, and Alien Carnage slotted perfectly into that ecosystem. Released on October 10, 1993, as Halloween Harry version 1.1 (with an incomplete 1.0 shareware demo exclusive to a UK magazine), the game pushed technological boundaries on DOS systems. Programmed in Pascal—a choice that later caused compatibility headaches on faster CPUs—it leveraged 256-color VGA graphics via routines by Tony Ball, parallax scrolling for depth, and MOD-format music by composers Stephen Baker, George Stamatiadis, and Neil Voss. This was Apogee’s first foray into full VGA for platformers, coinciding with contemporaries like Raptor: Call of the Shadows, amid a gaming landscape dominated by id Software’s Doom precursors and Sierra’s adventures.

The era’s constraints were palpable: 286/386 processors, 640KB RAM, and Sound Blaster cards defined the hardware ceiling. Developers navigated floppy-disk limitations (3.5″ or CD-ROM) and the absence of modern tools, relying on hand-drawn sprites and tracker music from the burgeoning MOD scene. Apogee’s vision was clear: create addictive, replayable levels with cinematic intros, positioning Halloween Harry as a non-seasonal powerhouse. By November 2, 1994, it was rebranded Alien Carnage (version 1.0), swapping episode orders (offices and sewers flipped) to optimize shareware playability—half the game free, ensuring viral spread. This strategic pivot, suggested by Apogee to avoid Halloween silos, lowered the price and broadened reach, though it orphaned the original title. Technical quirks, like runtime errors on speedy machines (fixable by disabling L2 cache), highlighted Pascal’s pitfalls, but the team’s passion shone through, blending Australian ingenuity with American shareware savvy in a pre-internet boom that made PC gaming explosively accessible.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Alien Carnage weaves a pulpy sci-fi horror tale set in 2030, where Earth teeters on the brink of subjugation by insidious aliens. The plot kicks off aboard Space Station Liberty, where protagonist Halloween Harry— a rugged, unnamed agent with a penchant for pyrotechnics—receives a dire briefing from his handler, Diane. Via grainy video link, she reveals the invaders’ modus operandi: kidnapping humans, cocooning them in viscous green slime, and transforming survivors into shambling zombies to bolster their ranks. The alien overlord issues an ultimatum—surrender the planet in 24 hours or watch civilization crumble—echoing Cold War paranoia and B-movie tropes like Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Harry, beamed planetside, becomes humanity’s lone bulwark, navigating infested urban wastelands to rescue hostages and dismantle the threat.

The narrative unfolds across four episodic missions—Sewers, Factories, Office Blocks, and the Alien Ship—each comprising five levels culminating in boss fights. Cinematic cutscenes bookend episodes, blending humor with tension: Diane’s flirtatious quips (“Watch out for those spikes, handsome!”) humanize the stakes, while Harry’s silent stoicism evokes a cyberpunk everyman. Characters are archetypal yet endearing; zombies reference pop culture (Elvis Presley clones, Gremlin-like pests, Aliens-inspired xenomorphs), infusing levity into the horror. Hostages, often women in distress, add emotional weight—rescuing them restores health and unlocks elevators, symbolizing heroism amid chaos. Some are mobile, wandering perilously; others immobilized by “green crap,” requiring puzzle-solving via color-coded switches to breach barriers.

Thematically, Alien Carnage delves into invasion anxiety, a staple of ’90s sci-fi post-Terminator, but with a cartoonish twist that undercuts dread. Zombies represent dehumanization and loss of agency, mirroring fears of technological overreach in an era of emerging internet and Y2K whispers. Harry’s jetpack-fueled rampage champions individualism—the lone hero versus hive-mind hordes—while Diane’s guidance nods to partnership, subverting isolationist tropes. Dialogue is sparse but punchy, delivered in MOD-accompanied briefs: warnings about secrets or dangers via collectible disks foster immersion. Underlying motifs of consumption abound—health via junk food (hot dogs, coffee, walnuts) satirizes American excess, while aliens’ zombification critiques conformity. Though plot depth is light (no branching paths or moral choices), its thematic synergy with gameplay elevates it beyond rote shooting, crafting a narrative of defiant humanity in a slime-soaked apocalypse.

Plot Strengths and Limitations

- Strengths: Tight pacing ties action to story; pop references (e.g., THX-1138 boss nod to George Lucas) reward cinephiles.

- Limitations: Linear structure lacks replayability; underdeveloped supporting cast (Diane’s role feels tokenized) misses opportunities for deeper lore.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Alien Carnage thrives as a side-scrolling platform shooter, distilling Apogee’s formula into a relentless loop of exploration, combat, and rescue. Core mechanics revolve around Harry’s dual-purpose flamethrower/jetpack: the former spews fiery arcs to incinerate zombies (yielding coins worth 5 credits each), while the latter propels him vertically, bypassing traditional jumps for fluid aerial maneuvers. Fuel is shared and finite, enforcing strategic restraint—overuse strands you mid-air or ammo-less against foes. Levels demand non-linear traversal: scour offices for hidden passages, flip colored switches to free blocked hostages, and activate terminals for saves. Elevators gate progress, accessible only after all rescues, blending puzzle-solving with action.

Combat evolves via vending-machine upgrades, purchased with coins from slain enemies or money bags (dropped by igniting green drums). Arsenal includes:

– Flamethrower: Default, ammo-hungry but versatile for crowds.

– Photon Gun: Rapid-fire energy blasts for precision.

– Missiles/Grenades: Explosive area denial, ideal for clusters.

– Micro-Nukes/Omega Bomb: Screen-clearing nukes, saved for bosses.

Power-ups abound: wrapped gifts refill current ammo, 1-up icons grant extra lives (with full health), and radar disks summon Diane’s hints on secrets or threats. Health depletes from zombie contact or spikes, replenished by quirky pickups or rescues (full restore). Three lives per episode reset to level starts (or terminals), with three difficulty tiers modulating enemy aggression and fuel costs.

Innovations shine in the jetpack’s “ditch-the-jumps” ethos, emphasizing momentum over pixel-perfect timing, and rotating disks that integrate narrative into gameplay—collect them for real-time tips, turning isolation into guided adventure. UI is minimalist yet effective: a heads-up display tracks health, fuel/ammo, credits, and hostages remaining, with smooth keyboard/mouse controls (Gravis pad optional). Flaws emerge in repetition—hostage hunts mimic key hunts—and fuel scarcity can frustrate novices, though secrets (e.g., walnut caches) reward mastery. Bosses, like the THX-1138 sentry droid, demand pattern recognition, culminating in epic ship assaults. Overall, the systems cohere into an addictive loop: kill, collect, upgrade, rescue—polished yet unforgiving, capturing Apogee’s essence.

Innovative Elements

- Jetpack Integration: Replaces jumps with flight, innovating mobility in a jump-heavy genre.

- Rescue Mechanic: Mandatory for progression, adding purpose beyond destruction.

Flaws in Design

- Fuel Management: Punitive on higher difficulties, potentially alienating casual players.

- Pascal Legacy Issues: Modern runs via DOSBox mitigate, but original runtime errors highlight era-specific bugs.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Alien Carnage‘s world is a dystopian 2030 metropolis warped by invasion: crumbling high-rises, fetid sewers, industrial factories, and biomechanical alien bowels form a parallax-scrolling tapestry of urban decay. Levels evoke a lived-in apocalypse—offices cluttered with desks and flickering monitors, sewers teeming with piping and sludge—fostering claustrophobic tension. Atmosphere builds through horror tropes: dim lighting casts eerie shadows on green-skinned zombies, while alien lairs pulse with organic horror, referencing Aliens in slime-draped corridors. World-building is subtle yet immersive; hostages’ plight humanizes the chaos, and environmental hazards (spikes, collapsing platforms) reinforce vulnerability.

Visually, Steven Stamatiadis’ art direction dazzles for 1993 VGA: 256 colors yield vivid palettes—fiery oranges against slimy greens—with lush details like animated zombie shambles and explosive particle effects. Parallax backgrounds add depth to side-scrolling, making factories feel vast. Cinematic sequences, with full-screen Harry briefings, elevate production values, though cartoonish style tempers gore for accessibility.

Sound design amplifies immersion: MOD tracks by Baker and Stamatiadis pulse with electronic synths—upbeat chiptunes for action, ominous drones for tension—rivaling Apogee’s best (e.g., Mystic Towers). Sound Blaster support delivers crunchy flamethrower roars and zombie gurgles, though PC Speaker fallbacks are tinny. A bundled Studio.exe (dropped in re-releases) lets players remix tunes, nodding to MOD culture. These elements synergize: visuals’ vibrancy contrasts horror, music’s energy propels gameplay, crafting an experience that’s equal parts thrilling and nostalgic, where every torching feels viscerally satisfying.

Reception & Legacy

Upon launch, Alien Carnage garnered strong praise, averaging 89% from critics like ASM (75-90%) and modern retrospectives (90-100% on sites like Hrej! and VictoryGames.pl). Reviewers lauded its “jaw-dropping VGA graphics,” “silky smooth controls,” and addictive flamethrower action, with Katakis on MobyGames calling it a game that “outsmarts any Apogee title.” Players echoed this, rating it 7.7/10 (3.7/5) based on 43 votes, praising its underappreciated charm despite nitpicks like repetition. Commercially, Apogee’s shareware model ensured modest success—bundled in anthologies and WizardWorks packs—though it sold steadily via mail-order, bolstered by re-releases (1994 CD-ROM, 1995 Netherlands edition).

Reputation evolved post-millennium: discontinued in 2000 due to Windows woes, it was freed as shareware in 2007 by 3D Realms (with Passfield’s blessing), recommending DOSBox for compatibility. This revitalized interest, landing it in 3D Realms Anthology (2014 Steam/Mac, 2015; Linux 2023 ports). Player reviews on Abandonware sites and Steam (5.1/10 user aggregate, positive 20 reviews) highlight nostalgia, with comments like “greatly underappreciated” from Tomer Gabel. Influence ripples through Apogee’s catalog—inspiring Duke Nukem‘s weaponry and Bio Menace‘s rescues—while its zombie-alien hybrid prefigured Zombie Wars (1996 sequel, featuring playable Diane and NPCs). Unrealized plans for a third game and animated series underscore untapped potential. In industry terms, it epitomized shareware’s democratizing force, paving ways for indie booms, and remains a benchmark for retro platformers, influencing modders and remakes in the freeware era.

Critical vs. Commercial Divide

- Launch Buzz: High marks for tech; seen as “Duke’s twin” by Zovni.

- Modern View: Freeware status boosts accessibility, though dated mechanics temper scores.

Conclusion

Alien Carnage is a combustible cocktail of Apogee innovation and ’90s excess: its VGA-fueled visuals, MOD-driven soundtrack, and jetpack-flamethrower synergy deliver pure, unadulterated fun amid zombie hordes and alien intrigue. From Passfield’s humble Microbee roots to its freeware resurrection, the game navigates development hurdles with spirited design, crafting a narrative of heroic defiance that resonates despite simplicity. Gameplay’s tight loops and atmospheric worlds outweigh flaws like fuel frustrations, while its reception cements a legacy as an accessible horror-platformer that influenced shareware’s golden age. Verdict: Essential for retro collectors—8.5/10. In video game history, Alien Carnage isn’t a revolutionary titan like Doom, but a fiery footnote that reminds us why we fell for PC gaming: because torching zombies with a jetpack never gets old. Fire it up in DOSBox today; your inner Harry awaits.