- Release Year: 2013

- Platforms: iPad, iPhone, Linux, Macintosh, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, Windows, Xbox One

- Publisher: Annapurna Games, LLC, Fullbright Company LLC, The, Headup Games GmbH & Co. KG, Majesco Entertainment Company, Midnight City

- Developer: The Fullbright Company

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Exploration, Puzzle elements

- Setting: 1990s, Contemporary

- Average Score: 87/100

Description

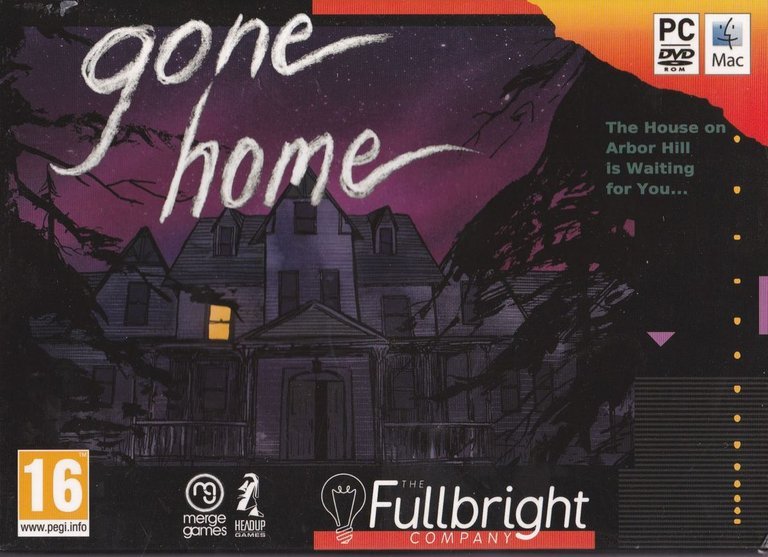

Gone Home is a first-person story-driven adventure game centered on exploration within a single deserted family house set in the USA on June 7, 1995. Protagonist Kaitlin Greenbriar returns from a long trip in Europe to find her parents and sister Samantha missing, with only a note from Sam urging her not to search; players freely investigate rooms and interact with everyday items like notes, letters, photographs, and household objects to piece together the family’s narrative through environmental clues and optional audio diaries, in a non-linear experience without traditional puzzles.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Get Gone Home

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (86/100): Gone Home does only one thing but does it superbly, telling a touching story solely through exploration that makes it well worth experiencing.

ign.com : Gone Home’s world just feels straight-up real.

eu.usatoday.com (88/100): it’s a refreshingly fun and atmospheric experience worthy of your time and $20 investment.

imdb.com : Gone Home is a unique bizarre little creature… tasteful, poignant, thought provoking and a brilliant story though it’s more of an experience than an actual video game.

Gone Home: Review

Introduction

Imagine stumbling through a rain-lashed night in 1995, suitcase in hand, only to find your family home—a sprawling, shadowed mansion—utterly deserted. No warm lights, no welcoming voices, just the creak of floorboards and the whisper of secrets etched into forgotten drawers. This is the haunting premise of Gone Home, a 2013 indie gem that thrust players into a quiet revolution: a video game that dares to forgo explosions and epic quests in favor of intimate, personal discovery. Developed by the nascent Fullbright Company, Gone Home arrived amid a gaming landscape dominated by blockbuster shooters and sprawling open worlds, yet it carved out a legacy as a pioneer of environmental narrative, proving that “walking simulators” could evoke deeper empathy and reflection than many action-packed epics. As a game historian, I’ve seen countless titles chase spectacle, but Gone Home endures as a testament to the medium’s potential for quiet profundity. My thesis: This unassuming exploration game not only redefined interactive storytelling by centering queer identity and familial dysfunction in a hyper-detailed domestic space but also democratized narrative depth, influencing a wave of introspective titles that prioritize emotional archaeology over mechanical bravado.

Development History & Context

The Fullbright Company—founded in 2012 by Steve Gaynor, Karla Zimonja, and Johnnemann Nordhagen—emerged from the ashes of their collaborative work on BioShock Infinite at 2K Games. Frustrated by the constraints of AAA development, the trio relocated to a modest Portland, Oregon house, transforming its basement into a makeshift studio to birth their debut. With a budget under $200,000 and a team of just three core members (bolstered by remote contributors like 3D artist Kate Craig and UI designer Emily Carroll), Gone Home was a deliberate pivot from high-stakes sci-fi to grounded realism. Gaynor, the lead writer and director, envisioned a “non-game” that stripped away combat and puzzles, drawing from BioShock‘s environmental storytelling but amplifying its introspective elements. Early prototypes, prototyped in the HPL Engine 2 before migrating to Unity 4, explored a smart house overrun by AI robots—a nod to System Shock‘s legacy—but the team quickly pared it down to a single, empty family home to keep scope manageable.

This restraint was born of necessity and vision: Fullbright’s small size precluded voice acting for all characters or complex animations, so they leaned into absence as a narrative tool. The 1995 setting was no accident; it predated ubiquitous digital communication, allowing analog artifacts like letters and cassettes to drive the plot without cell phones diluting the isolation. Technologically, Unity’s flexibility enabled rich interactivity—opening drawers, flipping lights—without demanding photorealism, though the era’s hardware limitations meant a focus on atmospheric lighting over graphical fireworks. Released on August 15, 2013, for PC, Mac, and Linux at $19.99, Gone Home entered a gaming landscape ripe for disruption. The indie scene was burgeoning post-Braid and World of Goo, with Kickstarter fueling personal tales like Papers, Please, but mainstream hits like Grand Theft Auto V and The Last of Us still equated immersion with violence. Fullbright’s output—17 months from concept to launch—challenged this, proving a tiny team could craft an emotionally resonant experience that felt revolutionary in its minimalism, influencing the “walking sim” genre’s rise.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its heart, Gone Home is a mosaic of unspoken truths, pieced together through the detritus of everyday life. You embody Kaitlin “Katie” Greenbriar (voiced by Sarah Elmaleh), a 21-year-old returning from a year abroad in Europe to the family’s new Oregon mansion, inherited from the reclusive Uncle Oscar. The plot unfolds non-linearly via exploration: no cutscenes, no overt guidance, just the player’s curiosity unraveling the past eight months. Central is Katie’s 17-year-old sister, Samantha “Sam” (Sarah Grayson), whose 23 audio diaries—triggered by key items—form the emotional spine. Sam’s entries chronicle her turbulent senior year: isolation in a new high school, rebellion via riot grrrl zines and punk cassettes (featuring real bands like Heavens to Betsy and Bratmobile), and her blossoming romance with JROTC cadet Lonnie DeSoto (voiced uncredited by Zimonja). What begins as teen angst evolves into a poignant coming-out story, as Sam grapples with her lesbian identity amid parental denial and societal pressures like “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

Subtler threads enrich the family tapestry. Father Terry (implied through notes and manuscripts) is a blocked sci-fi author, his Accidental series fixated on averting the 1963 Kennedy assassination—a cipher for his own buried trauma. Clues in the basement—Oscar’s safe (combination: 1963), a defaced portrait of his father, halted height marks—substantiate fan theories (later confirmed by Gaynor) of childhood sexual abuse by Oscar, an opiate-addicted recluse who sold his pharmacy for a dollar to evade “temptation.” Mother Janice’s arc hints at midlife discontent: a near-affair with coworker Rick, evidenced by concert tickets, a steamy novel, and a condom in her drawer, compounded by her promotion to wildlife conservation director straining the marriage. Their “anniversary camping trip” is revealed as a couples’ retreat, complete with self-help books on intimacy.

Thematically, Gone Home excavates the domestic as a site of hidden horrors and quiet triumphs. Home isn’t sanctuary but a “queer archive” (as scholar Florence Smith Nicholls terms it), where objects unearth suppressed identities—Sam’s posters and mixtapes versus Terry’s whiskey-stocked study. It confronts LGBTQ+ erasure with raw authenticity: Sam’s joy in her first kiss contrasts the terror of parental intervention, invoking conversion therapy pamphlets and fundamentalist overtones. Broader motifs include generational trauma (Terry’s abuse echoing in family dysfunction) and the “archaeological uncanny” (Moshenska, 2006), where familiar spaces turn alien through absence. Dialogue is sparse but potent—Sam’s voiceovers feel confessional, her evolving tone from loneliness to defiant hope underscoring themes of self-discovery and resilience. No villains emerge; instead, the narrative humanizes flawed individuals, culminating in Sam’s elopement with Lonnie, a bittersweet exodus funded by pilfered valuables like Terry’s laserdisc player. This layered, player-driven plot—flexible enough for missed clues—transforms Gone Home into an empathetic reconstruction of lives at crossroads, where silence speaks loudest.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Gone Home subverts traditional gameplay, embracing its “notgame” status (as player reviews note) to prioritize contemplative wandering over challenge. Core loops revolve around free-form exploration in the 24-room mansion: WASD movement and mouse-look in first-person, with interactions highlighted for drawers, doors, and objects. Pick up, rotate, and examine items—letters, photos, VHS tapes—to trigger insights; most serve narrative, not utility. Minimal progression gates access via four keys and codes (e.g., 1963 for Oscar’s safe), but these are intuitive, discovered through contextual clues like calendars or journals, avoiding frustration. No combat, no health bars, no failure states—innovation lies in emergent discovery, where players forge their path, backtracking at will.

The UI is elegantly sparse: a flashlight (toggleable) pierces the initial darkness, an optional map tracks explored rooms, and Sam’s diaries auto-collect in a menu for review. Inventory is vestigial, holding only plot keys like the bathroom combination (hinted by a calendar). Audio logs play on discovery, immersing without interruption, though the “put back” mechanic for objects adds tactile realism, letting players tidy without consequence. Flaws emerge in linearity’s guise: while non-linear, thoroughness is optional, leading to incomplete stories on first playthroughs (e.g., missing Terry’s basement horrors). Replayability is low—absent branching choices or randomization—exacerbating its 2-3 hour runtime, criticized as overpriced at launch ($19.99). Yet innovations shine: environmental interactivity (playing cassettes, flushing toilets) fosters immersion, making the house a reactive character. Developer commentary (added post-launch) enhances meta-analysis, with Gaynor et al. explaining design intent at hotspots. No progression trees or RPG elements; instead, “character growth” mirrors narrative piecing, rewarding curiosity over skill. This “interactive theater” (as one MobyGames review dubs it) deconstructs gameplay itself, challenging players to redefine engagement beyond adrenaline.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Greenbriar mansion on fictional Arbor Hill is a masterclass in microcosmic world-building: a ’90s Pacific Northwest relic, creaking with haikyo-inspired abandonment (Japanese urban ruins influencing Gaynor). Divided into floors—foyer clutter signaling recent move, Sam’s punk-strewn attic, Terry’s book-lined study, Janice’s greenhouse—it evokes a lived-in tomb, boxes half-unpacked amid riot grrrl flyers and wildlife posters. Atmosphere builds through spatial storytelling: dim halls foster unease, rain-lashed windows amplify isolation, while subtle details (a duck decoy hiding a key, Bibles clashing with Ouija boards) layer familial tension. Visually, Unity 4’s low-poly aesthetic prioritizes texture over fidelity—wood grains, cluttered shelves, faded photos—creating a tangible ’90s nostalgia without dated sheen. Lighting is pivotal: initial blackout forces light switches, revealing details gradually, mirroring revelation.

Sound design elevates immersion: Chris Remo’s original score—30+ minutes of ambient piano and strings—pulses with melancholy, swelling during diaries for emotional punctuation. Sam’s voice acting, raw and adolescent, conveys vulnerability; effects like thunder, dripping faucets, and cassette whirs ground the mundane horror. Licensed riot grrrl tracks (Heavens to Betsy, Bratmobile) blast from boomboxes, evoking Sam’s rebellion, while TV static and answering machine beeps add verisimilitude. These elements coalesce into a symphony of absence: the house “speaks” through echoes and objects, contributing to a pervasive unease that transitions from thriller tropes (ghostly creaks) to poignant intimacy. As one Polygon review notes, it’s a “nostalgia hit” for youth’s infinite-yet-tiny world, where every cranny whispers personal epic.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Gone Home polarized yet predominantly dazzled critics, earning an 86/100 on MobyGames (57 ratings) and 85/100 on Metacritic. Outlets like Giant Bomb, Polygon, and GamesRadar awarded perfect 100/100 scores, praising its “transcendent storytelling” and emotional heft—Polygon named it 2013 Game of the Year, hailing it as a “masterfully executed environmental storytelling” breakthrough. IGN (9.5/10) lauded its “powerful experience” evoking Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again, while GameSpot (9.5/10) celebrated its focus on “complex individuals” in a “believable story grounded in the real world.” Player scores averaged 7.9/10 on Moby (79 ratings), with praise for immersion but gripes over brevity and “not a real game” (one review likens it to “independent theater”). Commercially, it sold 50,000 copies in weeks, 250,000 by 2014, and over 700,000 by 2017, modest for indies but profitable, spawning ports to PS4/Xbox One (2016), Switch (2018), and iOS (2018) with Unity 5 upgrades.

Its reputation evolved from controversy—sparking “walking simulator” derision amid Gamergate’s 2014 backlash, where detractors decried its lack of “traditional” mechanics and LGBTQ+ themes—to veneration as a genre-definer. Fullbright’s withdrawal from PAX Prime over anti-LGBTQ+ remarks amplified its cultural impact, inspiring diversity initiatives. Legacy-wise, it birthed the walking sim boom: Firewatch, What Remains of Edith Finch, Tacoma (Fullbright’s follow-up), and even elements of Prey and Uncharted 4 echo its quiet moments. As Polygon reflected in 2019, it’s the decade’s most important game for shifting focus to exploration and underrepresented voices, influencing indie narratives on identity (e.g., Life is Strange). Academically cited over 1,000 times, it exemplifies games as art, challenging biases and paving for empathetic, non-violent interactivity.

Conclusion

Gone Home distills the essence of interactive fiction into two transformative hours: a rain-soaked homecoming that unearths a family’s fractures and rebirths through punk anthems and scribbled notes. From its scrappy indie origins to its emotional core—Sam’s queer awakening amid parental strife, Terry’s trauma-fueled reinvention— it weaves profound themes with surgical subtlety. Mechanically minimalist yet narratively rich, its world pulses with ’90s authenticity, sound and art conspiring to make absence profoundly present. Critically acclaimed and commercially viable, its legacy as a walking sim trailblazer endures, democratizing deep storytelling and affirming games’ artistic legitimacy. In video game history, Gone Home claims a pivotal perch: not just a debut, but a quiet manifesto proving that the most epic tales unfold in the ordinary, one drawer at a time. Definitive verdict: Essential, timeless—a 9.5/10 milestone that every gamer should wander through.