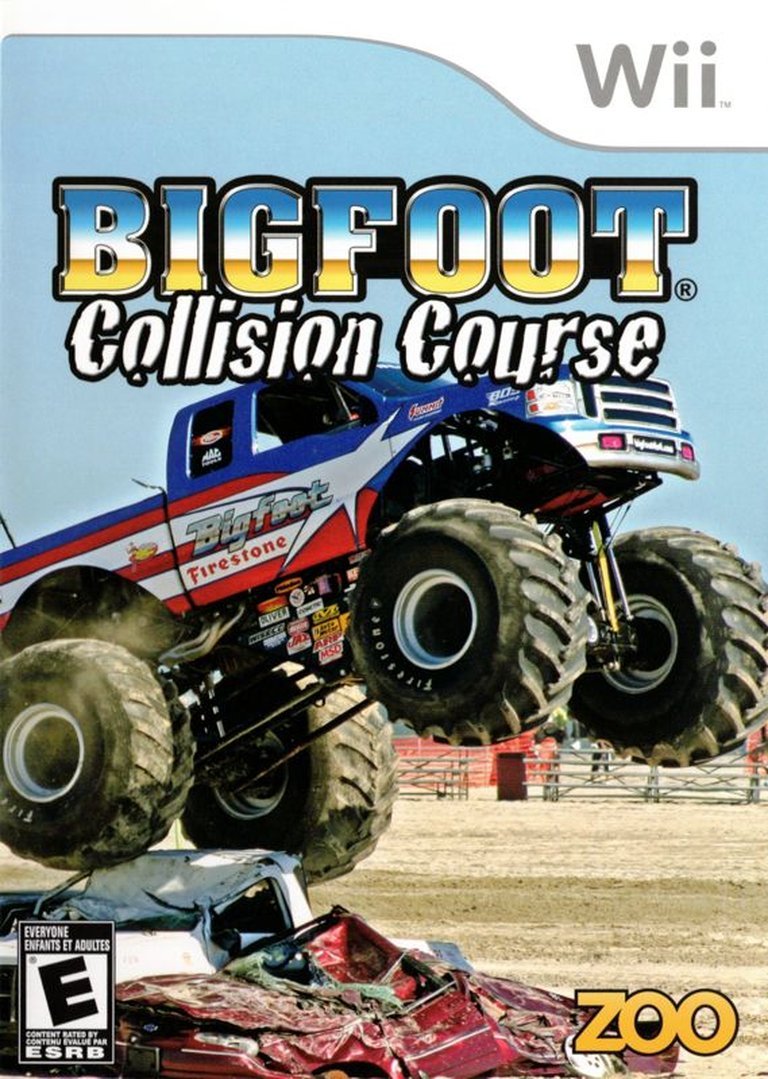

- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Wii, Windows

- Publisher: Zoo Games, Inc.

- Developer: Alpine Studios, Inc., Q90 Corporation

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Monster Truck driving

- Average Score: 25/100

Description

Bigfoot: Collision Course is a 2008 monster truck racing game developed by Destination Software and published by Zoo Games, centered around the legendary Bigfoot, the first monster truck. Players compete in high-octane races using three vehicle classes—light amateur monster trucks, pro stock monster trucks, and pro modified monster trucks—each with tailored course configurations that emphasize speed, destruction, and vehicular combat across various off-road and collision-heavy tracks.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (26/100): mildly enjoyable, if seriously flawed, racing romp

ign.com (21/100): Oh Bigfoot, how far you’ve fallen.

Bigfoot: Collision Course: Review

Introduction

In the roaring annals of video game history, few icons have bridged the gap between real-world spectacle and digital mayhem quite like Bigfoot, the legendary monster truck that kicked off an entire genre of automotive absurdity back in the late 1970s. Born from a backyard tinkering session in 1979 by truck enthusiast Bob Chandler, Bigfoot became synonymous with crushing cars, leaping over obstacles, and embodying the wild, unbridled spirit of American excess. Fast-forward to 2008, and the gaming world saw an attempt to immortalize this beast on consoles and handhelds with Bigfoot: Collision Course, a racing title that promised “mind-blowing 4×4 car-crushing action.” Yet, as a historian of interactive entertainment, I approach this game not as a triumphant revival but as a cautionary tale of licensed mediocrity. Developed amid the Wii’s motion-control boom and the DS’s portable dominance, Collision Course squanders its pedigree on simplistic mechanics and a lack of innovation, ultimately failing to rev the engines of excitement. My thesis: While it nods to Bigfoot’s cultural legacy, this game is a forgettable skid mark on the monster truck genre, more notable for its flaws than its features, serving as a reminder of how even iconic brands can stall out in the hands of under-resourced developers.

Development History & Context

The story of Bigfoot: Collision Course is one of opportunistic licensing meeting the tail end of the seventh console generation, a period when the gaming industry was awash in shovelware—budget titles rushed to market to capitalize on popular hardware like Nintendo’s Wii and DS. Published by Zoo Games (a subsidiary of Zoo Digital Publishing, known for family-friendly but often lackluster fare), the game was developed primarily by Destination Software, with contributions from smaller studios like Q90 Corporation and Alpine Studios. Credits reveal a modest team: 18 individuals for the Wii version, led by figures such as Pierre Roux (Vice President of Development, with a resume spanning over 80 games, many in the casual space) and Les Pardew (President, involved in 48 titles, often educational or licensed properties). Lead Programmer Richard Terranova and Lead Artist Daniel W. Whittington (credited as Dan Whittington) handled core technical and visual duties, while audio came from Eric Nunamaker, and even a licensed track like “Forgot About the Man” by Trevor Menear added a touch of polish.

Released on December 5, 2008, for Wii in North America—mere months after the financial crisis hit, squeezing budgets for non-AAA titles—the game arrived in a landscape dominated by polished racers like Mario Kart Wii (April 2008), which sold over 37 million copies with its accessible fun and multiplayer mayhem. The Wii’s motion controls were a hot commodity, promising intuitive steering via the Wii Remote, but Collision Course barely scratches that surface. Ports followed for Nintendo DS (January 9, 2009, NA) and Windows (January 9, 2009, NA; July 31, 2009, PAL), with planned but unfulfilled releases for PlayStation 2 in some regions. Technological constraints of the era played a role: The Wii’s underpowered hardware (729 MHz CPU, 88 MB RAM) limited graphical fidelity, while the DS’s dual screens and touch capabilities were underutilized. Zoo Games, riding the wave of licensed games (e.g., Jeep Thrills, another off-road title from the same team), aimed to tap into Bigfoot’s real-world fame— the truck had inspired earlier games like the 1990 NES title Bigfoot. However, the vision here feels diluted: Bigfoot 4×4 Inc., the licensor, sought to promote its anniversary models (like Bigfoot 30th Anniversary), but the result was a cookie-cutter racer built on recycled assets, emblematic of the mid-2000s budget boom where quantity trumped quality. In an industry shifting toward open-world epics like Grand Theft Auto IV (2008), Collision Course feels like a relic, constrained by its era’s push for quick, ESRB Everyone-rated cash-ins.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Bigfoot: Collision Course isn’t a game rich in storytelling; it’s a racing sim where plot takes a backseat to pedal-to-the-metal action, much like its genre forebears. The “narrative,” if it can be called that, follows a loose career mode framing the player’s ascent as a monster truck driver, culminating in a showdown against the “Original Bigfoot” itself—the 1979 Ford F-250 that started it all. This allusion to the Sasquatch mythos (Bigfoot as the elusive beast) is played straight in the ad blurb, positioning the truck as a mythical powerhouse, but in-game, it’s reduced to perfunctory cutscenes and menu text. You begin in the Amateur Circuit, progressing through Pro Stock and Pro Modified classes by earning points (36 for Pro Stock unlock, 40 for Pro Modified, 44 for the final Bigfoot Race), unlocking trucks like “The Original Bigfoot (Bigfoot 1),” “Bigfoot 4x4x4 (30th Anniversary),” and themed variants such as “Pink Bigfoot” (breast cancer awareness scheme) or “Blue Flame Bigfoot” (2008-2011 paint job).

Characters are absent in any meaningful sense—no drivers with backstories, no rival personalities barking taunts over the radio. Dialogue is minimal, limited to generic announcer lines like “Crush those cars!” during races, echoing the spectacle of real Bigfoot events but lacking depth. Thematically, the game channels the raw, destructive ethos of monster truck culture: innovation through chaos, as Bigfoot historically pioneered big tires and car-crushing stunts. Tracks evoke natural and industrial arenas—deserts, mountains, forests, winterscapes, and urban wastelands—symbolizing humanity’s conquest over terrain, with power-ups representing opportunistic boosts in a Darwinian race. Yet, this thematic potential fizzles; the “career” feels like a checklist, not an epic journey. Subtle nods to Bigfoot’s lore (e.g., playable trucks like “Bigwheels (Bigfoot 5)” or “Madusa Bigfoot”) honor the franchise’s 30-year history, but without narrative heft, it comes off as promotional fluff. In extreme detail, the progression mirrors real monster truck circuits: Amateur for light-hearted romps, Pro Stock for balanced competition, Pro Modified for high-stakes nitro-fueled battles. But absent are interpersonal drama or lore dumps—contrast this with Monster Truck Madness (1996), which wove promotional vignettes into its races. Ultimately, the themes of legacy and destruction are surface-level, undermined by repetitive loops that make the “story” feel like an afterthought, more ad than adventure.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Bigfoot: Collision Course is a straightforward arcade racer built around monster truck tropes: smashing obstacles, collecting power-ups, and outpacing AI foes across circuit-based tracks. The primary loop involves selecting a truck class—Light (Amateur) for nimble handling and low power, Pro Stock for balanced speed and durability, Pro Modified for aggressive boosts and heavy damage—and tackling races in varied environments. Single-player mode progresses through four circuits (Amateur unlocked at start; others via points), while Head-to-Head supports 2-4 players locally (1-2 on Wii/DS). Controls are basic: Wii Remote tilting for steering, acceleration/braking via buttons or shakes, with DS touch for menus but standard D-pad/stylus for driving. Power-ups—scattered nitro bursts, repairs, and “carnage” meters filled by crushing cars or obstacles—add bursts of chaos, charging a boost that propels you ahead, echoing real Bigfoot jumps.

Deconstructing the systems reveals both innovation and glaring flaws. Vehicle progression is tied to unlocks: Win races to access 15+ trucks (e.g., “The Stalker,” “Red Snake Bite,” “Dr. Bonez”), each with stats for speed, handling, and crush resistance, but customization is absent—no upgrades beyond basic repairs post-race. Tracks feature class-specific layouts: Amateur courses emphasize jumps and ramps for spectacle, Pro Modified adds tight turns and destructible environments for strategy. Combat is informal—ramming opponents yields points but risks flips—yet AI is predictably dumb, often veering into walls or ignoring power-ups, leading to unchallenging wins. The UI is cluttered: Wii’s widescreen menus feel ported from DS, with pixelated icons and laggy transitions; DS dual-screen splits track map above, but touch integration is minimal. Innovative elements include the “Season Mode,” a progressive campaign blending races and challenges (e.g., time trials, obstacle courses) to culminate in a Bigfoot boss race, but it’s shallow—17 races completable in under two hours, per critics. Flaws abound: Physics are janky, with trucks prone to unnatural flips on flat ground (reminiscent of the infamous Big Rigs: Over the Road Racing, earning a 2.0/10 from IGN for similar uncanny handling); no online multiplayer, limited replayability, and trial-and-error jumps frustrate without checkpoints. On PC/Windows, keyboard/joystick support adds accessibility, but low requirements (Pentium II 300 MHz, 64 MB RAM) highlight its dated engine. Overall, the mechanics promise destructive fun but deliver a pedestrian loop, lacking the depth of contemporaries like Burnout Paradise.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Bigfoot: Collision Course constructs a world that’s more diorama than immersive sandbox, prioritizing functional tracks over expansive lore. Settings draw from Bigfoot’s event history: arid deserts with sand dunes and car piles, forested trails mimicking rallycross, snowy mountains for slippery drifts, industrial yards with crushable machinery, and urban circuits evoking stadium shows. Atmosphere builds tension through escalating circuits—Amateur feels playful, Pro Modified chaotic with nitro flares and debris—but variety is superficial; tracks loop predictably, with “depth” from environmental hazards like mud pits or ramps rather than dynamic weather or day-night cycles.

Visually, the art direction is competent but uninspired, constrained by Wii/DS hardware. Models for trucks shine: Detailed Bigfoot variants (e.g., “Green Ghost Stang” with spectral decals, “Pink Bigfoot” for awareness) capture the brand’s chrome-and-tire aesthetic, with animations for crushing (cars crumpling realistically) and jumps (suspension compressing). However, environments are bland—low-poly textures, repetitive assets (endless identical cars to smash), and aliasing plague Wii renders. DS versions suffer more, with 2D sprites overlaying 3D tracks, leading to pop-in and frame drops. Sound design fares better: Roaring engines (authentic Bigfoot samples?) and crunching metal provide visceral feedback, amplified by power-up jingles and crowd cheers. The licensed track “Forgot About the Man” plays in menus, adding a rock edge, while Eric Nunamaker’s SFX (tire screeches, explosions) immerse during collisions. Yet, audio loops tiresomely—no dynamic soundtrack shifts—and announcer voiceovers are wooden. These elements contribute to a fleeting thrill: The crush mechanics heighten spectacle, making brief moments feel epic, but repetition erodes the atmosphere, turning potential chaos into monotonous noise.

Reception & Legacy

Upon launch, Bigfoot: Collision Course crashed and burned critically, earning a Metacritic score of 26/100 for DS (based on four reviews: 20/100 from GameSpot for its brevity, 20/100 from Gamers’ Temple for simplicity, 30/100 from Worth Playing for mismatched themes, 40/100 from GameZone for mild appeal to kids). Wii and PC versions fared similarly unremarked, with IGN’s 2.1/10 decrying its “painful” resemblance to glitchy racers. No player reviews on MobyGames, but user scores on Metacritic average 5.5/10, praising short-term fun for truck fans while slamming AI and length. Commercially, it flopped: VGChartz estimates 0.15 million units sold globally (0.14m NA DS, minimal elsewhere), dwarfed by Monster Jam rivals. Priced at $13-20, used copies now fetch $2-5, signaling obscurity.

Its reputation has evolved into cult curiosity rather than redemption—fandom wikis note its negative unanimity, while abandonware sites preserve it for nostalgia. Influence is negligible: It didn’t spawn sequels (unlike Bigfoot: King of Crush in 2011, a mobile pivot), but underscores the pitfalls of licensed shovelware, paving the way for better monster truck sims like Monster Jam Steel Titans (2019). In industry terms, it highlights the Wii/DS era’s oversaturation, where brands like Bigfoot enabled quick ports but diluted quality, influencing publishers to prioritize depth in later titles. As a historian, I see it as a footnote: A missed opportunity that reminds us legacy demands more than a logo.

Conclusion

Synthesizing its modest development, threadbare narrative, clunky mechanics, utilitarian world, and dismal reception, Bigfoot: Collision Course emerges as a relic of rushed ambition—a game that honors its namesake’s crushing spirit in theory but fumbles the execution. For die-hard monster truck enthusiasts or bargain-bin hunters seeking a 2-4 hour diversion, it offers fleeting crunches and unlocks; for anyone else, it’s skippable. In video game history, it occupies a lowly rung: Not the worst (that dubious honor goes to glitches like Big Rigs), but a stark reminder that even icons need strong steering to avoid the ditch. Verdict: 3/10—Approach with caution, or better yet, watch real Bigfoot highlights on YouTube for the authentic roar.