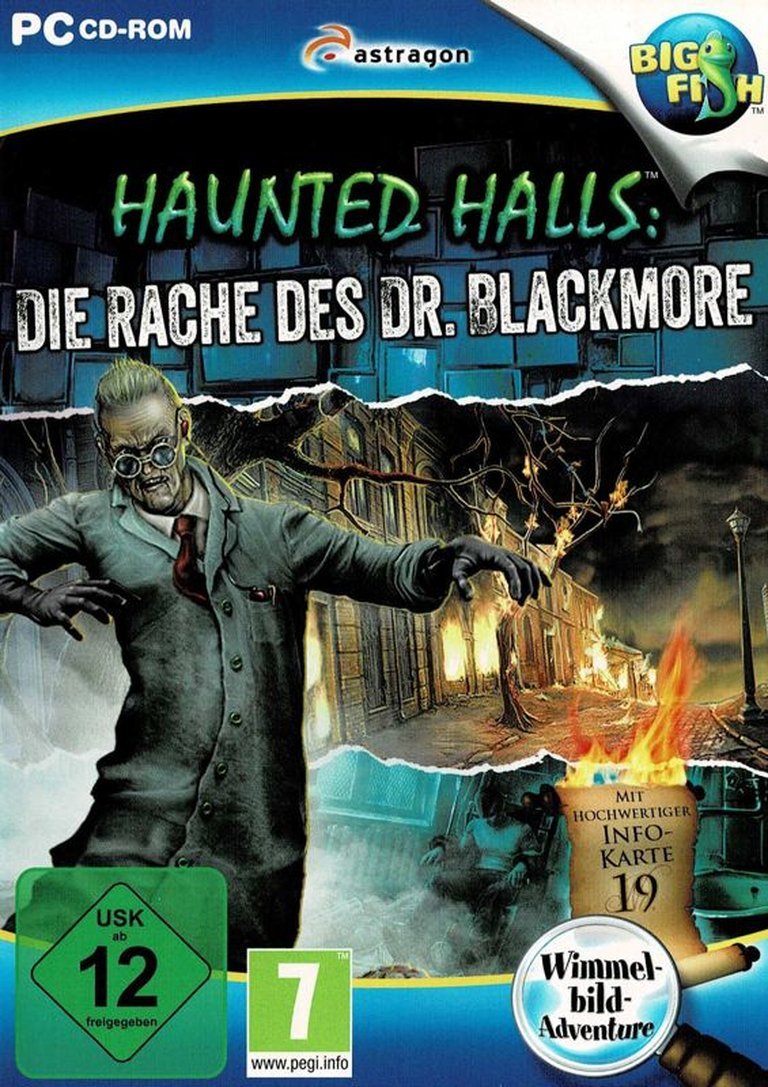

- Release Year: 2013

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc

- Developer: ERS G-Studio

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

In Haunted Halls: Revenge of Doctor Blackmore, players embark on a mind-bending hidden object adventure as a detective unraveling the vengeful plot of the sinister Dr. Blackmore, who has trapped victims—including the protagonist’s fiancé—in bizarre, haunted realms across various times and historical locations. Navigating eerie settings with first-person perspective, puzzle-solving mini-games, and detective mystery elements, the game challenges players to explore the weird and unexpected to rescue the trapped souls and thwart Blackmore’s revenge.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

Haunted Halls: Revenge of Doctor Blackmore: Review

Introduction

Imagine awakening in a labyrinthine lair, surrounded by grotesque experiments and the taunting holograms of a mad scientist who’s rewritten history just to settle a grudge. This is the disorienting hook of Haunted Halls: Revenge of Doctor Blackmore, the third installment in ERS Games’ quirky hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA) series. Released in 2012 amid the peak of casual gaming’s golden age, it builds on the eerie foundations of Green Hills Sanitarium (2010) and Fears from Childhood (2012), thrusting players into a time-hopping rescue mission against the vengeful Dr. Blackmore. As a game historian, I’ve seen countless HOPAs chase thrills through supernatural tropes, but this one stands out for its unapologetic weirdness—kangaroos in rocking chairs, ostriches hatching from vents, and portals to disasters like the Chicago Fire and Chernobyl. My thesis: While Revenge of Doctor Blackmore delivers inventive puzzles and a delightfully bizarre narrative that cements the series’ legacy as a cult favorite in casual horror, its uneven pacing, inconsistent mechanics, and controversial bonus content monetization reveal the era’s growing pains in the free-to-play-adjacent market, ultimately making it a flawed but memorable capstone to the Haunted Halls trilogy.

Development History & Context

ERS Games, a Ukrainian studio founded in the mid-2000s, specialized in crafting accessible yet atmospheric HOPAs for Big Fish Games, the dominant publisher in the casual gaming space during the early 2010s. Under the banner of ERS G-Studio (a subsidiary focused on graphical innovation), developers like Elena Afonina and the core team envisioned Revenge of Doctor Blackmore as a bold evolution of the series’ psychological horror roots. Drawing from the success of the first game’s sanitarium-set chills and the second’s childhood fear explorations, the team aimed to amplify the weird factor—blending mad science with temporal anomalies—to differentiate from competitors like Artifex Mundi or Elephant Games. The plot device of time portals, inspired by pulp sci-fi like H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine but filtered through B-movie aesthetics, reflected ERS’s vision of “mind-bending journeys into the realm of the weird,” as per the official ad blurb.

Technologically, the game was constrained by the era’s standards: built for Windows and Mac using fixed/flip-screen perspectives and pre-rendered 2D art assets to ensure smooth performance on modest hardware like 1.4 GHz CPUs and 1 GB RAM. This was the heyday of browser-based and downloadable casual games, where Big Fish’s portal dominated with titles emphasizing quick sessions and low barriers to entry. The 2012 landscape was saturated—Mystery Case Files and Mortimer Beckett series ruled sales charts—but ERS carved a niche with collectible editions (CEs), bundling extras like concept art and soundtracks to justify premium pricing ($6.99 standard, $9.99 CE). Release dates varied: September 27 for the standard edition on Big Fish, with a May 2013 MobyGames listing possibly reflecting a retail or international rollout. Amid economic recovery post-2008, casual games like this thrived on escapism, but monetization experiments (e.g., teasing incomplete stories) foreshadowed the freemium model’s rise, influencing later titles in the genre.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Revenge of Doctor Blackmore is a revenge-fueled detective mystery wrapped in temporal horror, where the player embodies an unnamed protagonist awakening in Blackmore’s fortified lair. The plot kicks off with a cutscene establishing the stakes: Dr. Blackmore, the cyborg-octopus hybrid villain from prior games (revived from outer space, no less), has kidnapped the protagonist’s fiancé and three others, sentencing them to perish in recreated historical disasters via interdimensional portals. Chapters unfold chronologically through these vignettes—starting in the modern lair (Chapter 1: Doctor Blackmore’s Return), then Chicago’s 1871 Great Fire (Chapter 2), Chernobyl’s 1986 meltdown (Chapter 3), Pompeii’s 79 AD eruption (Chapter 4), and oddly, a freezing Alaskan wilderness (Chapter 5)—culminating in a lair showdown. The narrative arcs toward empowerment, with the protagonist crafting antidotes and banishing hallucinations to free victims, but it’s punctuated by Blackmore’s holographic taunts, voiced with sneering charisma that elevates him beyond a stock mad scientist.

Characters are archetypal yet endearing in their simplicity: the fiancé is a passive damsel in the corner ward, pleading for rescue; victims like the restrained man in Chicago or the imprisoned woman in Pompeii offer perfunctory dialogue (“Please save me!”) that serves exposition rather than depth. Blackmore steals the show, his monologues dripping with nasty humor—mocking the player’s futile struggles while revealing his grudge against humanity. Dialogue is sparse and functional, delivered in limited voice acting that prioritizes atmosphere over nuance; lines like “Brace yourself for the unexpected!” from the synopsis set a tone of campy dread. Thematically, the game delves into revenge as a corrupting force, mirroring Blackmore’s transformation from scientist to monster, while exploring human resilience amid chaos. Time manipulation critiques hubris—disasters as “experiments” echo real historical traumas, blending education with horror. Yet, inconsistencies abound: Alaska as a “natural disaster” feels tacked-on, and random animal sidekicks (e.g., a bespectacled kangaroo or helpful beaver) inject whimsy that undercuts tension, emphasizing the series’ shift from psychological fears to absurdist weirdness. This thematic mishmash—mad science meets historical tragedy—creates a narrative that’s engagingly pulpy but narratively thin, rewarding players who embrace its eccentricity over those seeking emotional depth.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Revenge of Doctor Blackmore epitomizes HOPA design with a core loop of exploration, hidden object scenes (HOS), and mini-games, all in first-person perspective. Progression hinges on collecting key items (circled in red in walkthroughs) from interactive environments, solving puzzles to access portals, and crafting via the Portable Laboratory—a suitcase-shaped UI that appears when raw materials are found. Chapters average 30-45 minutes, with players navigating fixed scenes (e.g., Chicago’s fiery streets or Pompeii’s ashen courtyards) via glowing cursor arrows, using hints (recharging slower in Advanced/Hard modes) to highlight active zones.

HOS vary innovatively: traditional list-based (randomized items), silhouette-matching (non-random, cursor-teased previews), interactive assembly (e.g., building scissors from parts to reveal codes), and fragmented searches (piecing silhouettes). Two per chapter keep variety, but inconsistency—jumping from assembly to lists without warning—can frustrate, as noted in reviews. Mini-games shine as the mechanical highlight: gear alignments in the lair’s machine, pipe-connecting in Chernobyl’s well, or totem-assembly in Pompeii’s chest demand logical deduction, often with multiple steps (e.g., rotating segments or inputting codes like “268-47” from newspapers). Recurring elements add rhythm: hallucination banishments (using crafted items like Eye Drops or Pills), animal-assisted puzzles (feeding wheat to a chick for an ostrich path), and bomb-defusing (positioning hands via buttons). The Portable Lab innovates crafting—grinding flowers into powder, liquifying crystals—tying into themes of mad science, with 10-15 step sequences blending chemistry nods (e.g., mixing venom and lemon for acid).

Combat is absent, replaced by indirect confrontations like tomahawk-throwing at animated armor or banishing tentacles with extinguishers. Character progression is light: inventory bar (navigable via arrows) holds tools like the tomahawk or crowbar, with no upgrades but escalating complexity (e.g., Hard mode disables sparkles and text hints). UI is intuitive—menu for options, notes for clues—but cluttered in dense scenes, and the Skip button’s slow recharge in higher difficulties tests patience. Flaws include repetitive fetching (backtracking for items like the worm or hose) and the CE’s “bonus chapter” tease, which GameCola calls a “scam” by withholding content behind paywalls, shortening the base game to 3-4 hours. Overall, mechanics are solid for casual play, innovative in blending HOS with crafting, but pacing falters in longer chapters, making it accessible yet occasionally rote.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world-building thrives on juxtaposition: a sterile, gadget-filled lair (monitors clustering portals to disasters) contrasts vividly with historical recreations, fostering an atmosphere of disorienting weirdness. Settings evoke dread through detail—Chicago’s smoke-choked shacks with flickering flames, Chernobyl’s irradiated plazas littered with newspapers bearing codes, Pompeii’s ash-dusted courtyards guarded by sneezing bulls, and Alaska’s icy clearings with shipwrecks and chained bears. Portals serve as narrative glue, but the lair’s recurring motifs (e.g., Native American statues, pirate heads) add eccentric flavor, reinforcing Blackmore’s collector-like madness. Atmosphere builds via environmental storytelling: hallucinations warp reality (e.g., ghostly figures in school halls), while animal anomalies (kangaroos in test chambers, beavers carving ladders) inject surreal humor, contributing to a tone that’s more whimsically eerie than outright terrifying—less Fears from Childhood‘s psychological hauntings, more B-movie romp.

Visually, fixed/flip-screen art excels in pre-rendered 2D splendor: detailed hand-drawn scenes burst with cluttered interactivity (e.g., Pompeii’s herb-hung dining areas), using warm oranges for fires and sickly greens for radiation. Sparkles guide casual players, but higher difficulties demand keen eyes amid busy compositions. Animations are smooth but limited—tentacles writhing, statues animating—enhanced by subtle effects like drifting ash or melting ice. Sound design amplifies immersion: a haunting orchestral score swells during puzzles, punctuated by eerie drones and historical cues (crackling fires in Chicago, Geiger-like ticks in Chernobyl). Voice acting is sparse but effective—Blackmore’s gravelly taunts provide villainous flair, while ambient effects (dripping water, animal chirps) heighten tension. Collectively, these elements craft a cohesive, if bizarre, experience: the art’s richness draws players into the weird realm, while sound’s subtlety underscores themes of isolation and impending doom, making even mundane fetches feel perilously alive.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release in late 2012, Revenge of Doctor Blackmore garnered modest attention in the casual gaming sphere, with Big Fish sales buoyed by the series’ cult following but no widespread critical acclaim—MobyGames lists no scores, reflecting its niche status. Player feedback on forums and walkthrough sites praised its puzzles and weird charm, but complaints about length (3-4 hours base) and the CE’s “fake bonus chapter” (a withheld finale requiring extra purchase) drew ire; GameCola’s 5/5 “Average” review lambasts this as a “blatant scam,” akin to truncating a film. Commercially, it performed adequately for Big Fish, bundled later in Haunted Halls: Collection (2018), but didn’t chart like flagship HOPAs.

Over time, its reputation has warmed among retro enthusiasts, evolving from “short but sweet” to a quirky series endpoint—praised on Fandom wikis for concluding Blackmore’s arc, though critiqued for diluting horror with whimsy (e.g., Alaska’s odd inclusion). Influence-wise, it epitomizes early 2010s HOPA trends: time-travel mechanics inspired later Big Fish titles like Time Mysteries, while the portable crafting lab foreshadowed inventory systems in games like The Room series. In the broader industry, it highlights casual gaming’s shift toward monetized extras, prefiguring mobile freemium models and ethical debates in digital distribution. As a historian, I see it as a microcosm of the era—innovative yet imperfect, influencing indie HOPAs on Steam but overshadowed by AAA narratives. Its legacy endures in fan walkthroughs and Let’s Plays (e.g., 123Pazu’s video series), preserving its place as an underappreciated gem in casual horror history.

Conclusion

Haunted Halls: Revenge of Doctor Blackmore weaves a tapestry of mad science, historical peril, and animal absurdity into a HOPA that’s equal parts inventive and idiosyncratic, with standout puzzles, evocative art, and a narrative that revels in its weirdness. Yet, pacing inconsistencies, mechanical repetition, and exploitative bonus content temper its highs, revealing the commercial pressures of 2012’s casual market. As the trilogy’s finale, it satisfyingly ties Blackmore’s saga while embodying ERS Games’ bold experimentation. For fans of lighthearted horror HOPAs, it’s a worthwhile dive into the bizarre; for purists, a cautionary tale of genre evolution. Verdict: 7/10—a cult classic that earns its place in video game history as a quirky, if flawed, time-traveling triumph, deserving rediscovery amid today’s puzzle-adventure renaissance.