- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Idigicon Limited

- Genre: Educational, logic, Math

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Lifelines, Multiple Choice, Sudden Death, Timed

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

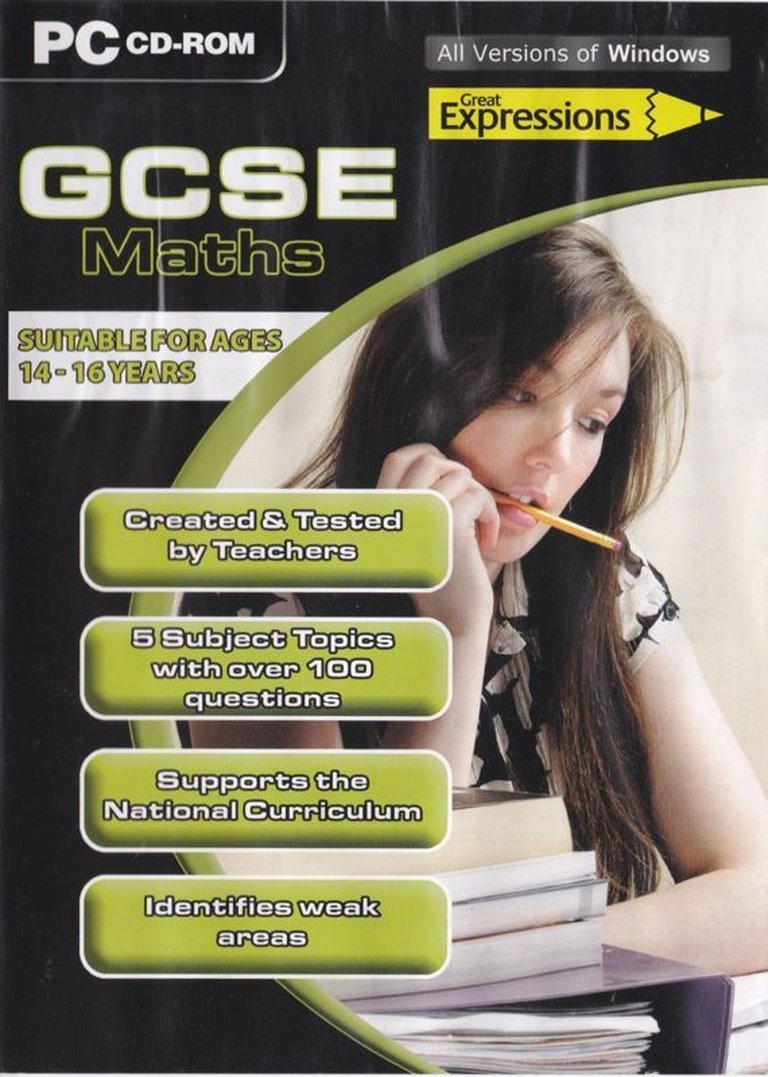

Great Expressions: GCSE Maths is an educational quiz game designed as a revision aid for UK teenagers aged 14-16 preparing for their GCSE mathematics exams, featuring over 100 multiple-choice questions drawn from a bank to create timed, random 10-question quizzes in a sudden-death format where the game ends on a wrong answer but offers three lifelines: removing two incorrect options, skipping questions, or gaining extra time. Marketed affordably through Poundland stores, the Windows-based title from 2008 emphasizes interactive learning via mouse controls for gameplay and keyboard input for high-score entries, blending straightforward quiz mechanics with logic-based math challenges in a first-person perspective.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Great Expressions: GCSE Maths: Review

Introduction

In the annals of video game history, few titles evoke the quiet heroism of educational software quite like Great Expressions: GCSE Maths, a 2008 relic from the Poundland bargain bins that transformed rote learning into a pulse-pounding quiz showdown. Released during a time when gaming was exploding into mainstream entertainment with titles like Grand Theft Auto IV dominating headlines, this unassuming edutainment program dared to blend the drudgery of GCSE mathematics revision with the tension of a game show. Aimed squarely at UK teenagers aged 14 to 16 preparing for their pivotal General Certificate of Secondary Education exams, it stands as a testament to the niche but vital role of budget educational games in bridging academia and interactivity. While it lacks the grandeur of blockbuster adventures, its legacy lies in democratizing math education through accessible, low-cost tech—proving that even the simplest mechanics can foster genuine engagement. My thesis: Great Expressions: GCSE Maths is a pioneering, if flawed, artifact of early 21st-century edutainment, whose innovative use of gamified tension elevates basic quiz formats into a surprisingly addictive tool for learning, influencing the subtle evolution of educational gaming despite its obscurity.

Development History & Context

The development of Great Expressions: GCSE Maths emerged from the modest confines of Idigicon Limited, a UK-based publisher and developer specializing in low-budget educational titles. Founded in the early 2000s, Idigicon focused on creating revision aids tailored to the British curriculum, leveraging the CD-ROM boom to distribute affordable software through discount retailers like Poundland. This game, released in 2008 exclusively for Windows PCs, was part of a broader “Great Expressions” series that included quizzes on subjects like English and science, all marketed as “Poundland: Revision Quiz” variants to capitalize on the chain’s reputation for £1 bargains.

The creators’ vision was pragmatic rather than revolutionary: to combat the monotony of GCSE prep by infusing quizzes with game-like stakes, drawing inspiration from TV shows like Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? (which popularized lifelines) and early edutainment hits like The Oregon Trail or Reader Rabbit. Idigicon’s team, likely a small group of educators and programmers without marquee talent, prioritized curriculum alignment over flashy production. The game’s specs reflect the technological constraints of the era—requiring only an Intel Pentium III processor, 256 MB RAM, DirectX 9.0, and a basic 4X CD-ROM drive—making it runnable on aging school computers or family PCs running Windows XP. This low barrier to entry was deliberate, ensuring accessibility in an age when broadband was still spotty and high-end gaming rigs were luxuries.

The broader gaming landscape in 2008 was a far cry from today’s mobile app-dominated edutainment scene. Consoles like the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 were pushing graphical boundaries with open-world epics, while the indie wave was just beginning with browser-based experiments. Educational games, however, occupied a marginalized space, often dismissed as “kiddie software.” Titles like World of Maths (2002) or Reader Rabbit Maths Ages 6-9 (1998) had paved the way, but they leaned on colorful animations rather than competitive tension. Great Expressions arrived amid economic pressures—the 2008 financial crisis made budget options like Poundland’s £1 discs a lifeline for cash-strapped families—positioning it as a stealthy counterpoint to the industry’s AAA excess. Its licensed, commercial model (tied to GCSE standards) underscored a vision of gaming as a societal tool, not just entertainment, though Idigicon’s obscurity meant limited marketing beyond in-store displays.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Great Expressions: GCSE Maths eschews traditional narrative arcs for a minimalist structure centered on the player’s journey through mathematical mastery—a meta-story of academic triumph over algebraic adversity. There is no overwrought plot or voiced protagonists; instead, the “narrative” unfolds as a series of 10-question quizzes drawn randomly from a bank of over 100 multiple-choice prompts covering GCSE topics like expressions, equations, inequalities, and basic geometry. The player’s avatar is implicitly themselves: a 14-16-year-old student racing against the clock to build confidence for real-world exams. This self-insertion creates a personal stakes-driven tale, where each correct answer propels the “hero” toward high-score glory, and a single error triggers sudden death, symbolizing the unforgiving nature of exam pressure.

Characters are absent in the conventional sense—no quirky hosts or animated mascots—but the game’s three lifelines personify supportive archetypes: the “remove two incorrect answers” lifeline acts as a wise mentor eliminating distractions; the “skip” option embodies resilience, allowing a momentary retreat; and “extra time” represents thoughtful introspection amid haste. Dialogue is sparse, limited to on-screen prompts like “Correct!” or “Time’s up!” delivered in plain, sans-serif fonts, evoking the stark efficiency of a classroom blackboard. This austerity amplifies the thematic depth: the game explores perseverance and strategic risk-taking, themes resonant with teenage exam anxiety. Underlying motifs of empowerment through knowledge critique the rote-learning paradigm, suggesting math isn’t a chore but a game to be won. In extreme detail, questions might probe simplifying expressions (e.g., “Expand (x + 2)(x – 3)”), forcing players to confront abstract concepts in a high-pressure format that mirrors the GCSE’s multiple-choice sections. The absence of a broader lore—unlike narrative-heavy edutainment like Math Blaster—highlights its thematic purity: learning as an intrinsic reward, unadorned by fluff, fostering a quiet rebellion against passive study methods.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Great Expressions: GCSE Maths distills edutainment to its essence: a core loop of timed quizzes punctuated by lifeline decisions, creating a surprisingly taut experience despite its simplicity. The primary gameplay revolves around 10-question sessions, where each prompt appears with four multiple-choice options, and players must select via mouse clicks within a strict timer—typically 30-60 seconds per question, though exact durations aren’t specified in available data. Random selection from the 100+ question bank ensures replayability, preventing memorization and encouraging genuine comprehension of GCSE maths like algebraic manipulation, substitution, and factorization.

The “sudden death” mechanic is the game’s innovative hook: one wrong answer ends the quiz, ratcheting tension akin to a permadeath roguelike but in quiz form. This flawlessly integrates risk management, as players ration three lifelines per session—eliminating two wrong answers (narrowing to a 50/50 guess), skipping (preserving momentum at the cost of a potential point), or gaining extra time (mitigating panic under pressure). These systems promote strategic depth; for instance, hoarding lifelines for tougher questions builds a meta-layer of resource allocation, rewarding cautious playstyles. Post-quiz, a high-score table (entered via keyboard) adds competitive longevity, potentially tracking total correct answers or survival streaks, though specifics are undocumented.

UI is utilitarian: a first-person perspective (likely a misnomer for a static screen view) centers the question in a clean window, with options below and a timer bar ticking down. Mouse-only navigation keeps it intuitive for young users, but the keyboard’s sole role in name entry feels tacked-on, a minor UI flaw exposing the game’s budget roots. Progression is linear yet emergent—unlocking nothing explicitly, but implicit growth via repeated quizzes hones skills, akin to skill trees in RPGs. Flaws abound: no adaptive difficulty means easy questions might frustrate advanced players, and the lack of tutorials could alienate beginners. Yet, innovations like lifeline integration elevate it beyond rote drills, creating addictive “one more try” loops that make math feel like a skill-based challenge rather than drudgery.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The “world” of Great Expressions: GCSE Maths is a Spartan digital classroom, devoid of expansive lore but rich in atmospheric minimalism that underscores its educational focus. Set in an abstract void—likely a plain white or pastel backdrop to avoid distracting from content—the game’s first-person perspective immerses players in a solitary study session, evoking the isolation of late-night revision. No explorable environments exist; instead, the setting is the quiz interface itself, a functional diorama of buttons, timers, and text boxes that builds tension through confinement, mirroring the pressure-cooker of exam halls.

Visual direction is stark and era-appropriate: low-res 2D graphics (suitable for 32 MB VRAM) feature basic icons for lifelines—perhaps a red “X” for elimination or a clock for time extension—and sans-serif text for questions, prioritizing readability over flair. Colors are subdued blues and whites, contributing to a clinical, focused atmosphere that aids concentration, though it risks visual monotony. Art contributes by stripping away excess, allowing maths to shine; the absence of animations (inferred from specs) keeps sessions snappy, preventing the bloat seen in flashier edutainment like JumpStart.

Sound design amplifies the experience’s intimacy: no orchestral scores or voice acting, but likely simple beeps for correct/incorrect answers—a satisfying “ding” for successes and a buzzer for failures—paired with a subtle timer tick to heighten urgency. Background music, if present, would be ambient and non-intrusive, perhaps soft chimes evoking a study hall, fostering immersion without overwhelming young learners. These elements collectively craft a cohesive, no-frills aesthetic: the game’s “world” isn’t built for escapism but for efficacy, where silence and simplicity enhance cognitive absorption, turning potential boredom into purposeful quietude.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 2008 launch, Great Expressions: GCSE Maths flew under the radar, receiving no critic reviews on platforms like Metacritic or GameFAQs, and zero player reviews on MobyGames—a Moby Score of n/a reflecting its obscurity. Commercially, it succeeded modestly as a Poundland exclusive, selling at £1 to budget-conscious UK families, with distribution via CD-ROM ensuring school adoptions. The lack of buzz stemmed from its niche appeal; in a year dominated by Super Smash Bros. Brawl and Fallout 3, edutainment rarely garnered press. User anecdotes (scarce online) suggest it was a hit in classrooms for its quick sessions, but commercial metrics remain elusive—likely thousands of units moved through discount chains.

Over time, its reputation has evolved into cult obscurity, preserved by retro enthusiasts on sites like MobyGames (added in 2014). No major controversies or rediscoveries have occurred, but its legacy endures in the gamification of education. By adapting game-show tropes to curriculum content, it prefigured modern apps like Duolingo or Khan Academy’s quizzes, influencing subtle shifts toward interactive learning tools. In the UK edutainment space, it echoes predecessors like Fun School: Maths (1997) while paving for post-2010 titles like Madu Maths (2017). Industrially, it highlights the value of accessible software in underserved markets, inspiring low-cost digital aids amid rising edtech. Though not revolutionary, its place as a bridge between 90s drill-and-kill games and today’s adaptive platforms cements a quiet influence—proof that even bargain-bin titles can shape pedagogical evolution.

Conclusion

Great Expressions: GCSE Maths is a diamond in the rough of educational gaming: a lean, tension-filled quiz that transforms GCSE revision into an engaging duel with numbers, bolstered by smart lifelines and random variety, yet hampered by minimalism and obscurity. Its development by Idigicon captured a era of budget innovation, while sparse narrative and mechanics cleverly gamify learning’s trials. Though visuals and sound prioritize function over form, they enhance focus; reception was muted, but legacy as an edutainment precursor endures. Ultimately, this 2008 curio earns a definitive verdict as a historical footnote—essential for understanding how games quietly revolutionized education, deserving emulation in today’s app-driven world. For math-wary teens or retro collectors, it’s a worthwhile curiosity; in video game history, a humble hero of hidden knowledge.