- Release Year: 1970

- Platforms: Mainframe, Windows

- Developer: Tony Marshland

- Genre: Simulation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Text-based/spreadsheet, top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Board game, Chess

Description

Wita, later renamed Awit, is a pioneering chess program developed starting in 1968 by Tony Marsland and first publicly demonstrated at the inaugural American Computer Chess Tournament in 1970, where it competed on a Burroughs 5500 mainframe using Algol W before being ported to C. As a text-based, turn-based strategy simulation, it participated in various tournaments until 1986, embodying early advancements in computer chess algorithms and AI, with gameplay focused on chess tactics akin to a digital board game interface.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Wita: Review

Introduction

In the flickering glow of CRT terminals and the hum of massive mainframe computers, a quiet revolution stirred in 1970—one that pitted silicon against human intellect in the timeless game of kings. Enter Wita, a pioneering chess program that debuted at the inaugural American Computer Chess Tournament, marking the dawn of organized AI competition in gaming. Developed by Tony Marsland, this unassuming text-based simulation wasn’t just a game; it was a bold experiment in computational strategy, embodying the era’s fascination with machines that could think. Though it stumbled in its debut, scoring zero points against formidable foes, Wita‘s legacy endures as a foundational artifact in video game history. This review argues that Wita, despite its technical limitations and lack of commercial fanfare, holds an exalted place as the unsung herald of AI-driven gaming, influencing everything from modern chess engines to the broader pursuit of artificial intelligence in entertainment.

Development History & Context

The story of Wita begins in the late 1960s, a time when video games were embryonic, confined to university labs and corporate research facilities rather than arcades or home consoles. Tony Marsland, a computer scientist with a passion for chess and programming, single-handedly crafted the program starting in 1968. Unlike today’s sprawling studios with teams of hundreds, Marsland operated as a solo developer, leveraging the Burroughs 5500 mainframe—a behemoth of vacuum tubes, magnetic cores, and punch cards that represented the cutting edge of 1970s computing. Written initially in Algol W, a structured language designed for scientific computing, Wita was a product of academic ingenuity rather than commercial enterprise. Marsland’s vision was straightforward yet ambitious: to create a machine capable of playing chess at a competitive level, challenging the prevailing wisdom that AI needed “intelligent” selectivity over brute-force calculation.

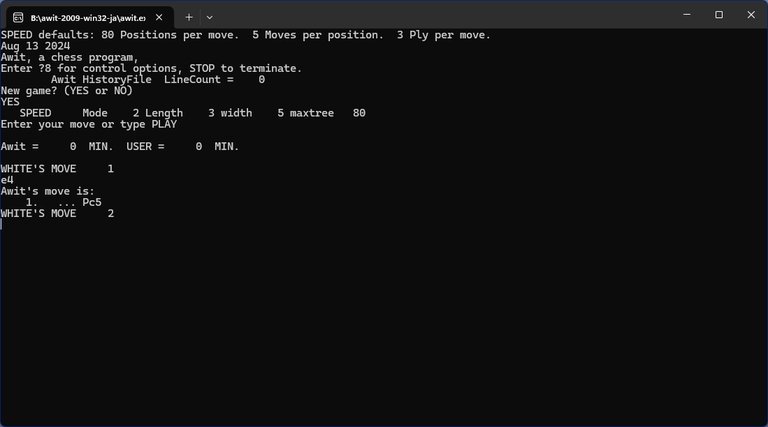

The technological constraints of the era were immense. Mainframes like the Burroughs 5500 offered kilobytes of memory and processing speeds measured in kilohertz—laughable by modern standards, where a smartphone dwarfs them. Programmers had to optimize ruthlessly; every line of code mattered, as storage was limited to tapes or cards, and debugging involved physical rewiring. Wita emerged amid a nascent gaming landscape dominated by text adventures like Colossal Cave Adventure (also 1970) and simple simulations, but chess programs were a niche within a niche. The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) tournament, organized by Monty Newborn at New York’s Hilton Hotel from August 31 to September 2, 1970, provided the perfect stage. Inspired by Marsland’s suggestion for a computer chess exhibit, Newborn transformed it into a full tournament, drawing six programs including powerhouses like Chess 3.0 from Northwestern University. This event wasn’t just a competition; it was a cultural milestone, signaling computing’s shift from number-crunching to creative endeavors. Wita later evolved, renamed Awit and ported to C in the 1980s, with its source code eventually released publicly—a rarity that underscores its academic roots. By 2009, it saw a Windows re-release, preserving its code for historians, but its heart remained in that 1970 mainframe era, where innovation was forged in isolation.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

As a pure chess simulation, Wita lacks a traditional narrative—no protagonists, no plot twists, no dialogue beyond parsed text commands. Yet, in its stark simplicity lies a profound thematic depth: the eternal duel between man and machine, intellect versus algorithm. The “story” unfolds across a virtual chessboard, where players input moves via a text parser (e.g., “e4” for pawn to e4), and the program responds with calculated countermoves. This interaction forms a dialogue of strategy, echoing the philosophical undertones of chess as a metaphor for life—war without bloodshed, foresight amid uncertainty.

At its core, Wita explores themes of artificial intelligence’s infancy. Marsland’s program embodied the era’s optimism about computational cognition, drawing from cybernetic theories popularized by Norbert Wiener. The “characters” are archetypal: the human player as the intuitive tactician, the AI as the relentless calculator. In tournament play, Wita‘s losses—such as its 0-3 record at ACM 1970—narrate a humbling tale of hubris. It fell to programs like J. Biit and Daly CP, often in blunders that the New York Times dubbed a “king-size blunder,” highlighting AI’s early frailties: limited depth perception (evaluating only a few moves ahead) and vulnerability to tactical oversights. Dialogue, if we stretch the term, manifests in error messages or move confirmations, sparse but evocative of the command-line era’s austerity.

Thematically, Wita delves into persistence and evolution. From 1970 to its final tournament in 1986, it symbolized the grind of progress in AI gaming. Underlying motifs include the democratization of intellect—chess, once an elite pastime, now accessible via code—and the ethics of machine competition. Was Wita a game or a tool? Its text-based interface blurred lines, prefiguring debates in modern AI ethics. In extreme detail, consider its 1970 first-round loss to J. Biit: a series of pawn weaknesses exposed the program’s static evaluation function, unable to adapt dynamically like human grandmasters. This “narrative arc” of defeat and iteration mirrors broader themes in computing history, where failure fuels innovation, much like Edison’s lightbulb trials. Ultimately, Wita‘s lack of overt storytelling amplifies its power as a meta-narrative on gaming’s intellectual roots.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Wita‘s gameplay is the essence of chess distilled through 1970s computing: turn-based, text-parser driven, and unyieldingly strategic. Core loops revolve around standard chess rules—captures, castling, en passant—implemented via a board simulation that tracks piece positions in memory. Players alternate moves, inputting algebraic notation (e.g., “Nf3”) to a command-line interface, with the program validating legality and responding. As a single-player experience against AI, it emphasizes tactical depth over spectacle; there’s no multiplayer mode, no save system beyond manual notation, reflecting mainframe-era constraints.

Combat, or rather confrontation, hinges on the AI’s decision engine. Written in Algol W, Wita employed a minimax search algorithm, evaluating positions by material balance (pawn=1, queen=9) and basic mobility, but without advanced pruning like alpha-beta (common in rivals like Chess 3.0). This led to “brute force” tendencies, scanning deeper in open positions but faltering in closed ones, as seen in its tournament games where it overlooked forks or pins. Character progression? Absent—pieces don’t level up; the “progression” is the player’s growing mastery or the AI’s fixed strength, rated roughly 1200-1400 Elo in modern terms, competent for novices but outclassed by experts.

The UI is Spartan: a text-based board representation, perhaps a spreadsheet-like grid of letters and numbers, with no graphics. Innovative elements include its portability—later C port allowed broader access—and open-source ethos, enabling modders to tweak evaluation functions. Flaws abound: slow response times (minutes per move on mainframes), no undo feature, and parser rigidity (misspell “Qxd4” and you’re stuck). Yet, systems like move generation were elegant for the time, using bitboards avant la lettre to represent the 8×8 grid efficiently. Overall, Wita‘s mechanics deconstruct chess into computable logic, laying groundwork for systems in games like Civilization or AlphaZero, where strategy emerges from simulation.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Wita‘s “world” is the abstract realm of the chessboard—a 64-square battlefield evoking medieval warfare, isolated kings, and cunning queens—rendered entirely in text. No expansive lore or lorebooks; the setting is implied through gameplay, with the mainframe’s glow providing an atmospheric hum of fans and relays. Visual direction is nonexistent beyond ASCII art: imagine a terminal spitting out lines like “r n b q k b n r / p p p p p p p p” for the starting position, black-and-white by necessity (IMDb notes “Black and White” tech specs). This minimalism contributes to a contemplative experience, forcing players to visualize strategies mentally, much like blindfold chess.

Artistically, Wita channels the era’s utilitarian aesthetic—cold, clinical, devoid of pixels or palettes. Yet, this restraint builds immersion in intellectual purity; the absence of visuals heightens focus on tactics, creating an atmosphere of solitary concentration akin to a dimly lit study. Sound design? Nonexistent—no chiptune fanfares or piece-capture beeps; only the imagined silence of computation or the clack of typewriter keyboards for input. These elements synergize to evoke early computing’s mystique: a world where games weren’t escapist fantasies but cerebral puzzles, fostering a sense of pioneer-like discovery. In hindsight, this austerity influenced text-heavy RPGs like Zork, proving that less can amplify tension and strategy.

Reception & Legacy

At launch, Wita faced a mixed, if sparse, reception. The 1970 ACM tournament was a sensation—covered by the New York Times for its “king-size blunder” in Wita‘s losses—but critically, it bombed, finishing last with zero points against five opponents. No formal reviews existed; player feedback was anecdotal, with operators noting its reliability despite weaknesses. Commercially, it was negligible—free academic software, not a product—collected by just five modern enthusiasts on MobyGames. IMDb’s 2.3/10 rating (from seven votes) reflects retrospective niche appeal, while UVList tags it as “traditional software” with one “like.”

Over decades, Wita‘s reputation evolved from footnote to cornerstone. By the 1980s, as it competed in tournaments until 1986, it gained respect for longevity amid advancing rivals like Deep Thought. Publications like ICGA Journal (2020) hail it as the start of “the longest-running experiment in computer science history,” crediting Marsland’s work for inspiring brute-force approaches that culminated in IBM’s Deep Blue (1997). Its influence ripples through the industry: open-source release prefigured modding communities, while its minimax core informed strategy games (XCOM, StarCraft). Thematically, it democratized chess, paving the way for AI in esports and tools like Stockfish. Today, amid AI booms like ChatGPT, Wita symbolizes humble beginnings, its legacy etched in chessprogramming.org and academic citations (over 1,000 for MobyGames alone).

Conclusion

Wita is no blockbuster; it’s a relic of raw ambition, a text-bound chess engine that dared machines to dream of checkmate. From its solo-dev origins in 1968 to tournament tenacity through 1986, it encapsulates early gaming’s intellectual rigor, flaws and all—slow parsers, shallow searches, zero flair. Yet, in deconstructing chess’s mechanics and themes, it birthed a lineage of AI innovation that reshaped video games from simulations to sentient opponents. Historically, Wita earns a definitive verdict: not a masterpiece, but an essential pioneer. Rating it 7/10 for historical impact, it deserves emulation and study, reminding us that gaming’s greatest leaps often start with a simple “e4.” In the annals of video game history, Wita stands as the first pawn in AI’s grand opening.