- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Akella, DreamCatcher Interactive Inc.

- Developer: Legacy Interactive Inc.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Courtroom simulation, Cross-examination, Detective Investigation, Evidence Collection, Mystery, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Law enforcement, Law practice, New York

- Average Score: 72/100

Description

Law & Order II: Double or Nothing is an adventure game set in the gritty streets of New York City, where players take on dual roles as a detective and prosecutor to solve a high-stakes murder case inspired by the iconic TV series. Beginning with the discovery of a victim in a car, players must meticulously investigate crime scenes, question dynamic witnesses, process evidence through labs and departments, secure warrants, and build an airtight case for trial, all while adhering strictly to legal procedures to avoid courtroom setbacks and achieve a guilty verdict.

Gameplay Videos

Law & Order II: Double or Nothing Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (74/100): It may be a conventional, paint-by-numbers murder mystery, but the resulting portrait is a rather generous one that provides two unique perspectives, a complex story, and hours of fun.

gamespot.com : If you have even a passing interest in Law & Order, you should give Double or Nothing a look.

Law & Order II: Double or Nothing: Review

Introduction

In the gritty underbelly of 2003’s adventure game scene, where point-and-click mysteries jostled for attention amid the rise of 3D blockbusters like Half-Life 2 and Doom 3, Law & Order II: Double or Nothing emerged as a procedural drama distilled into pixels—a digital courtroom where the badge of justice weighed heavier than any inventory puzzle. As the second entry in Legacy Interactive’s adaptation of Dick Wolf’s iconic TV franchise, it built on the foundation of 2002’s Law & Order: Dead on the Money, promising fans a chance to step into the shoes of New York’s finest detectives and prosecutors. Yet, for all its procedural rigor, the game reminds us that not every case closes with a tidy verdict; some linger in the files of mediocrity. My thesis: Double or Nothing is a faithful, if flawed, tribute to the Law & Order ethos—excelling in narrative immersion for series devotees but stumbling in innovation, leaving it as a niche relic rather than a genre-defining triumph in video game history.

Development History & Context

Legacy Interactive, a boutique studio founded in 1987 and helmed by visionaries like Ariella Lehrer (Ph.D.) as executive producer and Christina Taylor Oliver as director, specialized in licensed adventure titles that bridged pop culture and interactive storytelling. By 2003, the Montreal-based outfit had carved a niche in TV tie-ins, having previously tackled properties like Murder, She Wrote and The Weakest Link. For Double or Nothing, their goal was clear: refine the formula of the first game, which had sold modestly but drawn criticism for its rigid time limits and clunky interface. Writers Douglas Stark and Dick Wolf himself contributed to the script, ensuring the game’s “ripped from the headlines” vibe mirrored the show’s blend of real-world ethics and dramatic flair—here, weaving genetic engineering controversies into a murder plot, echoing early-2000s debates on biotech ethics post-Jurassic Park and cloning headlines.

Technological constraints of the era played a pivotal role. Built on a custom engine using motion-capture for animations, the game ran on Windows PCs with Pentium III processors and 128MB RAM—humble specs compared to the GeForce 4-era GPUs pushing graphical frontiers elsewhere. This led to a static, “boxed” 3D perspective: full panning views but no free-roaming exploration, a holdover from pre-Myst III adventure tech. Legacy’s small team (76 credits, including QA leads like Mike Mitres) prioritized voice acting over visuals, securing reprisals from Jerry Orbach, S. Epatha Merkerson, and Elisabeth Röhm, whose likenesses were scanned for authenticity. Publishers like DreamCatcher Interactive (North America/Europe) and Akella (Russia) handled distribution, but the game’s CD-ROM format and ESRB Teen rating limited its reach to casual PC gamers.

The 2003 gaming landscape was one of transition: adventure games were fading against RPGs like Knights of the Old Republic and shooters like Call of Duty, yet procedural sims like CSI: Dark Motives (also 2003) proved demand for detective titles. Double or Nothing released in North America on October 1 (EU November 21), capitalizing on the show’s 13th season buzz, but faced headwinds from a saturated market and its predecessor’s lukewarm reception. Patches addressed glitches (e.g., cursor lockups, sound drops), but a 2007 UK controversy—using an unaltered CCTV still of the tragic James Bulger abduction—forced a temporary recall and image removal, underscoring ethical pitfalls in asset sourcing for licensed games.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

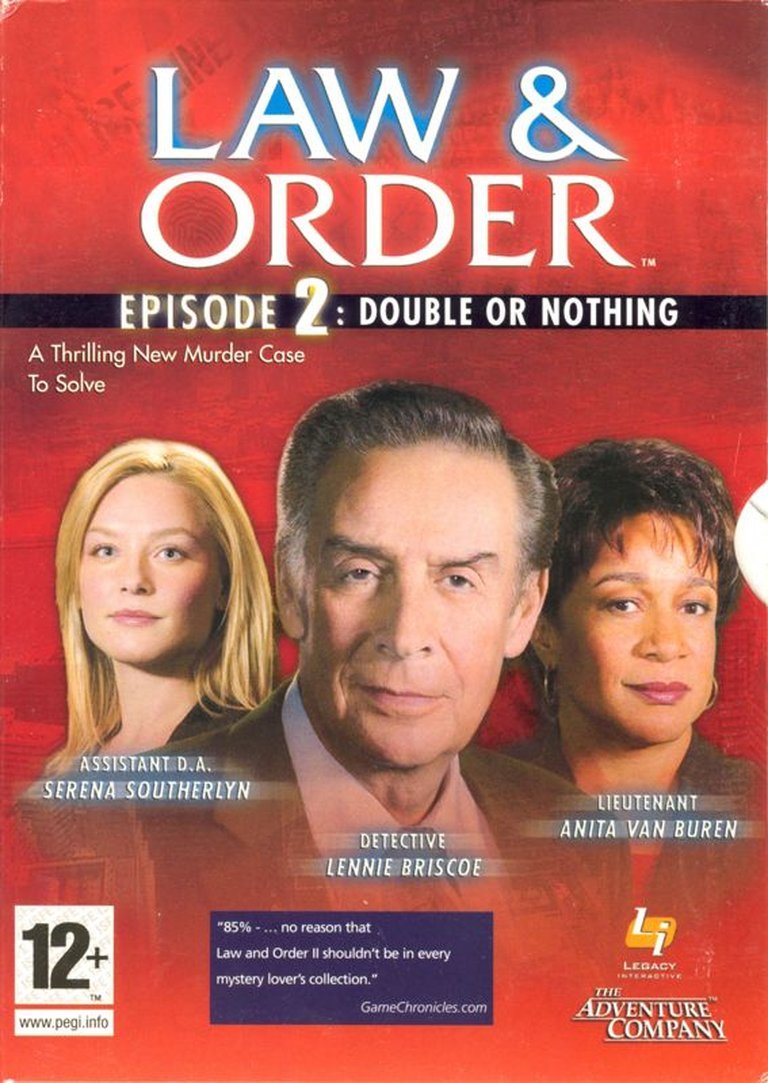

At its core, Double or Nothing unfolds as a taut, two-act procedural: the investigation of a geneticist’s shooting in his Midtown Manhattan car, followed by a courtroom battle to secure a guilty verdict. The plot kicks off with the victim, Dr. Richard Blythe (voiced by Jeff Harlan), slumped over his wheel— a seemingly random hit that unravels into a web of corporate intrigue, illicit affairs, and biotech espionage. Partnering with the grizzled Detective Lennie Briscoe (Jerry Orbach’s gravelly timbre intact), players scour crime scenes, interview a colorful cast (e.g., the evasive Paul Kim by Keone Young, or the ethically torn Dr. Ann Galloway by Keri Tombazian), and dispatch evidence to labs. Mid-game, the baton passes to Assistant District Attorney Serena Southerlyn (Elisabeth Röhm, delivering poised but occasionally stiff line reads), who navigates subpoenas, cross-examinations, and objections under the watchful eye of a game-original DA, Douglas Wade (Victor Brandt).

Characters shine through their Law & Order authenticity: Lieutenant Anita Van Buren (S. Epatha Merkerson) provides commanding oversight, her dialogue laced with precinct banter that grounds the player’s rookie status. Supporting roles, like defense attorney Miles Duncan (James Handy) or Judge Emily Greenwood (Florence Stanley in her final role), add procedural depth—objections hinge on hearsay rules or chain-of-custody lapses, forcing players to recall investigative missteps. Dialogue is sharp and dynamic: questioning branches based on prior evidence, with redos for botched interviews preventing dead-ends, a nod to the show’s improvisational twists. Yet, scripts occasionally falter in exposition dumps, revealing motives (e.g., financial embezzlement tied to genetic patents) through clunky research reports.

Thematically, the game probes the intersection of law and morality in a post-9/11 New York, where “futuristic means” like genetic manipulation clash with “traditional desires” (jealousy, greed). It echoes the series’ ripped-from-headlines ethos—biotech scandals mirroring real 2000s cloning debates—while critiquing systemic flaws: evidence inadmissibility due to warrant oversights underscores due process fragility. Subtle motifs of identity (cloned secrets) and justice’s double-edged sword emerge, but the narrative’s linearity curbs deeper exploration, prioritizing verdict over moral ambiguity. Clocking 10-15 hours, it’s a satisfying puzzle of human frailties, though lacking the emotional gut-punches of contemporaries like Syberia.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Double or Nothing eschews combat for cerebral loops: investigate, evidence-gather, prosecute. Core gameplay splits into detective and DA phases, unified by the “briefcase” UI—a drag-and-drop hub for inventory, suspect files, and actions. As detective, players navigate static scenes (pannable 360-degree views) to collect items—no pixel-hunting, as hotspots glow—but discernment is key: an inventory cap forces discards, with no retrieval, mirroring real case triage. Evidence processing involves requesting analyses (ballistics, psych evals) from departments; results arrive via phone cues, blending waiting with strategy. Warrants assemble via click-combos: link suspect profiles to proofs (e.g., surveillance photos tying alibis to lies), a satisfying “eureka” mechanic that rewards thoroughness.

Interviews are dynamic: multiple-choice questions unlock branches, but wrong paths can alienate witnesses (e.g., aggressive probing on affairs yields hostility). Redo options mitigate frustration, an improvement over the first game’s permanence. Progression ties to milestones—arrests unlock trials—without overt leveling, though skill selection at start (e.g., “interview skills” prunes bad options, “evidence collection” highlights items) shapes difficulty. Two skills max add replay value, but locking them post-start frustrates experimentation.

The trial phase innovates with courtroom simulation: select witnesses/evidence, then question via tiered dialogues, objecting to defense queries (e.g., relevance, speculation). Objections use multiple-choice rulings, with judges (like Greenwood) sustaining based on logic—flawed picks weaken your case score, potentially forcing recess investigations. No multiplayer exists despite Wikipedia’s note (likely erroneous), and the single case lacks branches, though mid-trial clues enable pivots.

Flaws abound: UI feels clunky—briefcase menus overload with tabs—and linearity (one path to victory) stifles agency. Puzzles lean logical (warrant assembly) over obtuse, suiting casuals, but glitches (patched cursor freezes) and guesswork (fading hotspots late-game) disrupt flow. Patches fixed crashes, yet the system’s Eurocentric (T for Teen, mild blood/violence) belies its intellectual rigor. Overall, it’s accessible procedural sim, innovative in legal fidelity but flawed by repetition.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Set in a bustling yet abstracted New York City, Double or Nothing evokes the show’s urban pulse without sprawling openness. Locations—precincts, labs, high-rises—feel procedural: Midtown streets hum with implied traffic, crime scenes scarred by yellow tape. Atmosphere builds through narrative cues—rain-slicked alleys mirror moral murk—but world-building is sparse; no deep lore beyond Law & Order canon, focusing on case silos over systemic NYC grit.

Visually, it’s a product of 2003’s budget constraints: low-res 3D models (blocky characters, pasted-on lip-sync) in static panoramas, panning fluidly but evoking a “box” diorama. Textures are adequate—grimy car interiors, sterile labs—but dated, paling against Beyond Good & Evil‘s vibrancy. Motion-capture lends believable gestures (Briscoe’s weary slouch), yet animations stutter, and no dynamic lighting persists. It’s functional for immersion, not spectacle, prioritizing readability for evidence hunts.

Sound design elevates the package: Orbach’s world-weary quips and Merkerson’s authoritative barks anchor authenticity, with supporting cast (e.g., Richardson as suspect Mark Rawlins) delivering nuanced menace. Scripts crackle with idiom—”shunned off” realism—but Röhm’s delivery borders wooden. Music is minimal—pulsing synth intros set tension, fading to silence elsewhere—while SFX (footsteps, phone rings) are sparse, amplifying procedural quietude. Subtitles and options (graphics tweaks, unlimited saves) enhance accessibility, but absent ambiance (no city hum) leaves scenes feeling isolated. Collectively, these elements forge a courtroom drama vibe: austere, tense, and show-true, contributing to empathetic immersion for fans, though underwhelming for sensory seekers.

Reception & Legacy

At launch, Double or Nothing garnered mixed reviews, averaging 69% on GameRankings and 74/100 on Metacritic—praised for narrative fidelity but dinged for dated tech. Critics like Adventure Gamers (80%) lauded its “deep, quality mystery” and no-time-limit freedom, calling it a “peeling onion” of twists sans tears from the first game’s flaws. Armchair Empire (80%) highlighted writing and TV translation, deeming it a “solid purchase for fans.” Yet, outlets like GameStar Germany (29%) branded it a “Frechheit” (outrage)—stale puzzles, poor graphics—while PC Gamer UK (35%) slammed its blandness. Player scores echoed: MobyGames’ 3.6/5 noted “potential unmet,” with Jeanne’s 2005 review praising concept but critiquing presentation.

Commercially, it underperformed: PC Data tracked 37,714 North American units by December 2003, modest against CSI‘s sales. The 2007 Bulger controversy briefly tarnished its rep, prompting a patch and withdrawal in the UK, highlighting insensitivity in asset use. Post-launch, reputation stabilized as a fan service—bundled in Adventure Chest 2 (2005)—but evolved little; modern retrospectives (e.g., Wikipedia) frame it as “average to mixed,” influential in procedural subgenre yet overshadowed by L.A. Noire (2011).

Legacy-wise, it paved the Law & Order series (Justice is Served, Criminal Intent), influencing tie-in sims like CSI sequels by emphasizing dual-phase (cop/prosecutor) play. It underscored licensed games’ pitfalls—authenticity vs. innovation—and boosted casual adventure’s appeal amid genre decline. Though not revolutionary, it preserved TV-to-game adaptation as viable, inspiring later efforts like Ace Attorney.

Conclusion

Law & Order II: Double or Nothing stands as a procedural purist’s delight: a meticulously scripted homage that lets players wield the scales of justice, refining its predecessor’s edges into a more playable whole. Its narrative depth and voice-cast charisma capture the TV show’s pulse, while mechanics like dynamic questioning and objection systems deliver intellectual thrills. Yet, dated visuals, linear structure, and technical hiccups cap its ambition, rendering it a comfortable but unremarkable adventure in 2003’s crowded docket.

In video game history, it occupies a footnote as a bridge between episodic TV and interactive mystery—valuable for Law & Order aficionados, emblematic of licensed games’ highs and lows. Verdict: 7/10—a guilty pleasure for procedural fans, but not compelling enough to acquit its era’s limitations. If you’re a series devotee craving digital dun-dun, prosecute this case; otherwise, let it rest in the archives.