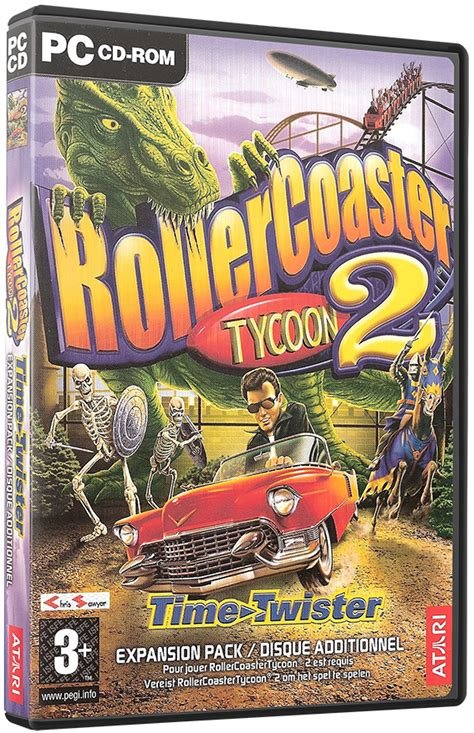

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Atari Interactive, Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 / RollerCoaster Tycoon 2: Time Twister is a compilation release that bundles the core simulation game RollerCoaster Tycoon 2, where players take on the role of a theme park tycoon, designing intricate roller coasters, managing attractions, staff, and finances to create successful amusement parks, with its second expansion pack, Time Twister, which adds time-travel mechanics enabling the construction of parks in diverse historical eras like ancient Rome or the Wild West, blending strategy, creativity, and economic management in a vibrant, isometric world.

Gameplay Videos

RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 / RollerCoaster Tycoon 2: Time Twister: Review

Introduction

In the pantheon of simulation games that defined the early 2000s, few titles evoke the pure joy of creative construction and meticulous management quite like RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 (RCT2). Released in 2002, it built upon the groundbreaking foundation of its 1999 predecessor, expanding the sandbox of theme park tycoon gameplay into a sprawling canvas for imagination. This 2003 compilation, bundling the base game with the Time Twister expansion pack, represents a pinnacle of the series’ classic era—a time when pixelated parks and physics-defying roller coasters captured the hearts of millions. As a game journalist and historian, I’ve spent countless hours dissecting the evolution of tycoon simulations, and my thesis here is unequivocal: RCT2 / Time Twister isn’t just a game; it’s a timeless blueprint for emergent storytelling through systems, cementing Chris Sawyer’s legacy as a virtuoso of interactive design. In an age dominated by first-person shooters and RPG epics, this compilation offered a serene escape into world-building, where success was measured not in kill counts, but in guest happiness and profit margins.

Development History & Context

The story of RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 begins with Frontier Developments, a British studio founded in 1994 by David Braben (co-creator of Elite) and others, but the true architect was independent developer Chris Sawyer. A Scottish programmer with a passion for simulations, Sawyer had single-handedly coded the original RollerCoaster Tycoon using a custom 3D engine built around 2D isometric sprites—a feat of efficiency that bypassed the era’s graphical bloat. For RCT2, released in October 2002 by Infogrames (later rebranded as Atari), Sawyer expanded this vision, collaborating with a small team to introduce 3D terrain modeling and enhanced coaster customization. The Time Twister expansion, launched in 2003, was developed by Sawyer’s team in tandem with ATI Research, adding thematic flair with time-travel elements.

The early 2000s gaming landscape was a transitional period: Windows PC dominated, with hardware like Pentium III processors and GeForce 2 graphics cards pushing isometric views and basic 3D. Tycoon games were niche but booming—titles like SimCity 3000 (1999) and Zoo Tycoon (2001) popularized god-like management sims amid a sea of console blockbusters (Grand Theft Auto III, 2001). Technological constraints shaped RCT2’s design; Sawyer’s engine prioritized performance over photorealism, rendering vast parks on modest 256MB RAM systems without crashes that plagued contemporaries like The Sims. Atari’s publishing arm, fresh off acquiring Infogrames’ catalog, bundled RCT2 with Time Twister in 2003 to capitalize on the series’ 4 million+ sales, targeting budget-conscious families. This compilation reflected the era’s shift toward value-packed releases, mirroring expansions in MMOs like EverQuest. Sawyer’s vision was pure: democratize theme park design, inspired by real-world parks like Blackpool Pleasure Beach, where he honed coaster physics through meticulous research.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 eschews traditional narratives in favor of procedural storytelling, a hallmark of the tycoon genre that Time Twister amplifies through its expansion’s conceit. There is no overt plot or voiced characters; instead, the “story” emerges from the player’s role as an invisible park magnate, tasked with transforming barren landscapes into thriving attractions. Scenarios—over 25 in the base game, plus Time Twister‘s 10 historical epochs—serve as episodic vignettes, each with objectives like achieving visitor counts or profits within time limits. In the base game, parks range from sunny coastal resorts to urban sprawls, implicitly narrating tales of ambition and peril: a poorly placed coaster might lead to “disasters” like guest drownings or breakdowns, echoing themes of hubris in Icarus-like engineering failures.

Time Twister introduces a loose thematic framework by warping parks through time—build amidst roaring ’20s speakeasies, prehistoric jungles, or futuristic spaceports—infusing a sense of adventure absent in the original. Dialogue is minimal, limited to tooltip flavor text (e.g., “Guests are vomiting on the paths!”) and staff banter in thought bubbles, which humanize the simulation without overwhelming it. Underlying themes revolve around creativity versus constraint: players grapple with financial woes, vandalism, and mechanical realism, mirroring real-world capitalism’s joys and pitfalls. The expansion’s time-travel motif explores impermanence—era-specific rides like dinosaur coasters or Viking longships underscore how innovation builds legacy, yet entropy (weather, breakdowns) reminds us of fragility. Critically, this absence of linear narrative empowers replayability, turning each park into a personal epic. No deep character arcs exist, but guests and staff become archetypes: the nauseous family man, the diligent mechanic—proxies for societal dynamics in a capitalist playground. In extreme detail, these elements critique consumerism; high guest happiness correlates with spending, satirizing how entertainment extracts value from joy, a theme prescient for today’s microtransaction-heavy industry.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, RCT2 / Time Twister revolves around a masterful gameplay loop of construction, management, and iteration, deconstructing theme park simulation into accessible yet depth-laden systems. Players start with a budget and plot, building paths, rides, shops, and scenery via an intuitive isometric interface. The standout innovation is the coaster editor: a physics-based tool allowing custom tracks with loops, corkscrews, and inclines, tested via virtual peeps (guests) who react realistically—excitement scores influence nausea and satisfaction. Base game mechanics include resource management (finances, staffing), research trees unlocking rides, and a UI with tabbed windows for landscaping, finances, and guest tracking—flawless for its era, though the lack of undo buttons frustrates micromanagement.

Time Twister enhances this with era-locked mechanics: prehistoric scenarios demand dinosaur-handling systems, while space-age parks introduce zero-gravity coasters, adding progression layers without combat (a non-issue in this peaceful sim). Character “progression” manifests in park evolution—start with basic Ferris wheels, advance to behemoths like the Steel Twister—tied to profits and research. Flaws emerge in pathfinding AI; guests can clump or path into hazards, leading to chaos, and the economy sim occasionally balloons into unmanageable debt. UI quirks, like buried menus for scenery rotation, demand patience, but innovations like underground tunnels and water rides (expanded from RCT1) reward experimentation. No overt combat exists, but “peep management” feels tactical: hire mechanics to avert breakdowns, market to boost attendance. The loop is addictive: build, test, tweak, expand—culminating in sandbox mode for infinite creativity. Multiplayer is absent, focusing on solitary mastery, with Time Twister‘s scenarios introducing timed challenges that elevate tension. Overall, these systems create emergent narratives, where a viral coaster can save a failing park, blending strategy and whimsy seamlessly.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The worlds of RCT2 / Time Twister are vibrant dioramas of imagination, rendered in a charming isometric 2D style that prioritizes clarity over spectacle. Base game settings span idyllic countrysides to bustling cities, with terrain tools allowing hills, lakes, and forests—world-building feels god-like, as players sculpt ecosystems around rides. Time Twister excels here, layering thematic atmospheres: Victorian eras brim with gas lamps and top hats, while Wild West towns feature saloons and cacti, each with period-accurate props that deepen immersion. Visual direction is economical yet evocative; sprite-based guests animate with subtle flair—waving arms, puking expressions—while coasters’ dynamic physics (swaying cars, splashing water) convey life without 3D overhead.

Art style contributes profoundly to the experience, evoking a toy-like wonder that contrasts the era’s gritty realism (e.g., Max Payne, 2001). Colors pop—neon coaster tracks against green meadows—fostering a sense of boundless possibility, though low-res textures show age on modern displays. Sound design is understated but effective: the hum of crowds, clacking coaster wheels, and cheerful chiptune melodies (composed by Sawyer and Allister Brimble) build atmosphere without intrusion. Ambient effects, like guest chatter or storm rumbles, heighten tension during disasters, while upbeat tracks swell during peak attendance. In Time Twister, era-specific audio—distant dinosaur roars or futuristic whooshes—reinforces thematic immersion, making worlds feel alive and reactive. Collectively, these elements transform abstract management into a sensory playground, where visual feedback (rising guest meters) and auditory cues (distant screams) make successes visceral and failures comically poignant.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, RCT2 garnered critical acclaim, scoring 89% on Metacritic equivalents and selling over 4 million copies by 2003, propelling Atari’s portfolio amid the post-RCT1 hype. Time Twister received solid but less fervent praise (around 80% averages), lauded for creative scenarios but critiqued for minor bugs in time-specific mechanics. The 2003 compilation, aimed at newcomers, flew under the radar commercially but boosted series longevity, especially in budget markets. No MobyGames critic reviews exist for this bundle (n/a score), underscoring its status as a fan-favorite curio rather than a standalone blockbuster.

Reputation has evolved into reverence; fan mods and OpenRCT2 (an open-source remake) keep it alive, with Time Twister‘s quirky eras inspiring nostalgia streams on YouTube. Its influence is profound: RCT2 popularized coaster builders in Planet Coaster (2016) and Parkitect (2018), while tycoon mechanics shaped Cities: Skylines (2015) and mobile hits like Theme Park Tycoon 2 on Roblox. Sawyer’s engine influenced indie sims, emphasizing accessibility. Commercially, the series spawned RCT3’s 3D shift (2004), but classics like this compilation endure as purist benchmarks—evidenced by 2017’s RCT: Classic ports. In industry terms, it democratized simulation design, proving small teams could rival AAA scale, and its legacy lies in fostering creativity in an increasingly narrative-driven medium.

Conclusion

RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 / RollerCoaster Tycoon 2: Time Twister stands as a monument to simulation excellence— a compilation that distills the series’ essence into a perfect blend of base-game depth and expansion ingenuity. From Sawyer’s visionary development to its emergent themes of creation and chaos, innovative mechanics, and evocative worlds, it captures the thrill of building dreams amid practical constraints. While flaws like dated UI persist, its reception and enduring influence affirm a definitive verdict: this is essential video game history, a 9.5/10 masterpiece that reminds us why we game—to craft, manage, and revel in our own virtual empires. For historians and players alike, it’s not just playable nostalgia; it’s the blueprint for joyful interactivity.