- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Markus Sabadello

- Developer: Markus Sabadello

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Hotseat, LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

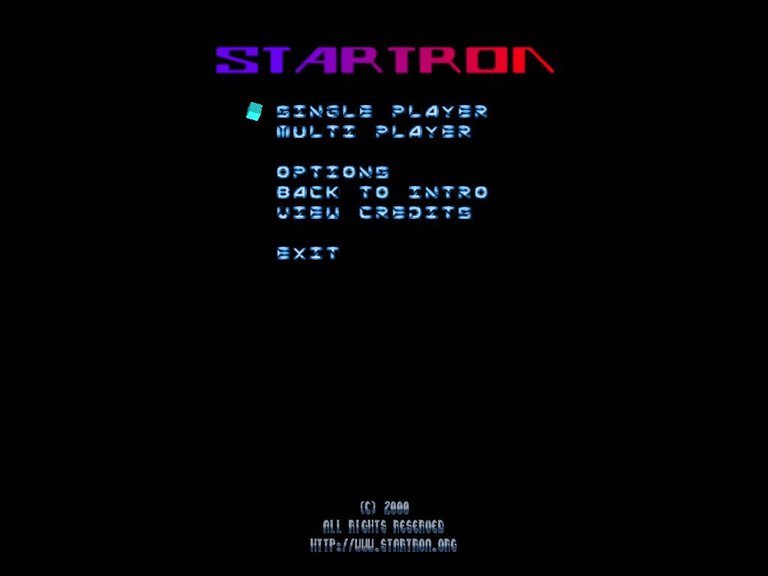

Startron is a sci-fi arcade game where players pilot a spaceship across a two-dimensional surface in a futuristic setting, leaving behind a trail that functions as an impassable wall—colliding with it results in a crash. The objective is to collect colorful crystals scattered on the field, with collected items persisting after each death as the trail resets; spanning three worlds with 24 levels, it offers a third-person 3D view behind the ship or an optional top-down 2D perspective, and emphasizes multiplayer competition where up to eight players aim to trap opponents using their trails.

Where to Buy Startron

PC

Startron Free Download

PC

Startron: A Forgotten Gem of Early 2000s Indie Arcade Gaming

Introduction

Imagine hurtling through a neon-lit void on a sleek spaceship, your every maneuver etching a fatal trail of light behind you—one wrong turn, and it’s game over in a spectacular crash. This is the addictive thrill of Startron, a 2000 freeware Windows title that channels the spirit of arcade classics like Tron‘s light cycles and Pac-Man‘s maze-chasing frenzy into a sci-fi wrapper. Released at the dawn of the new millennium, Startron emerged from the indie scene as a passion project, quietly influencing the light-cycle genre while fading into obscurity amid the rise of 3D blockbusters. As a game historian, I’ve pored over archived downloads and fragmented reviews, and my thesis is clear: Startron is a testament to resourceful indie development, blending simple yet elegant mechanics with a poignant narrative of human resilience, earning it a rightful place as an underappreciated artifact of early PC freeware gaming.

Development History & Context

Startron was the brainchild of Markus Sabadello, a solo developer who handled both management and software development for this Windows-exclusive title, released on December 21, 2000. Operating in an era before widespread indie platforms like Steam, Sabadello crafted the game using accessible tools of the time, likely leveraging early 3D engines or custom code to render its hybrid 3D/2D perspectives. The credits reveal a small but dedicated team: Robert Glashuettner contributed the soundtrack and storyline, infusing the project with narrative depth, while Lukas Stattin designed the 3D objects, giving the ships and environments a polished, futuristic sheen despite modest resources. A whopping 18 beta testers—names like Christina Baptist, Andreas Engl, and Tobias Wessely—ensured the game’s multiplayer stability, a rarity for freeware.

The technological constraints of 2000 were stark: PCs varied wildly in specs, with DirectX just gaining traction and broadband a luxury. Startron navigated this by sticking to keyboard controls and lightweight downloads (around 5MB, per archived files), making it accessible on era-typical hardware without demanding high-end graphics cards. The gaming landscape was shifting dramatically—The Sims and Half-Life dominated retail shelves, while freeware sites like Caiman.us hosted hidden gems for hobbyists. Indie development was nascent, fueled by shareware culture, and Startron fit perfectly as public domain software, downloadable for free but begging for community support. Sabadello’s vision, evident in the Tron-inspired “light cycle” group tag on MobyGames, was to modernize arcade purity with sci-fi lore, creating a multiplayer arena game that echoed LAN parties of the dial-up age. Tragically, the listed website (http://www.startron.org) was a dead end even at launch, symbolizing the fragility of early online distribution—yet the game endured via mirrors like Archive.org.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Startron‘s story is a compact sci-fi epic, unfolding through in-game text and level intros rather than voice acting or cutscenes—a budget-conscious choice that amplifies its thematic intimacy. Set in 2838, the narrative opens with cataclysm: Earth and swathes of the solar system obliterated in a nuclear world war, forcing humanity to colonize distant planets. This loss breeds vulnerability; twenty years later, the technologically superior Yolons—ruthless alien conquerors—enslave the scattered Terrans in a “furious race through space.” Resistance crumbles, and most humans resign to servitude, their spirits dulled by years of oppression.

Enter the protagonists: a cadre of “legendary startron-explorers,” plucky rebels who dare to return to Earth’s ruins in search of “superior technology hidden in the ashes.” The plot casts the player as one of these fighters, tasked with battling aliens, collecting crystals (symbolizing lost artifacts or energy sources), and reclaiming humanity’s destiny. Dialogue is sparse but evocative—brief logs and mission briefs delivered in Glashuettner’s straightforward prose, like calls to “discover the startron-explorers, battle the aliens, fly home, and free your people!” No named characters dominate; instead, the narrative personifies the ship as an extension of the pilot’s will, emphasizing themes of isolation and defiance.

Thematically, Startron grapples with loss and redemption in a post-apocalyptic cosmos. Earth’s destruction mirrors real-world anxieties of the Y2K era and Cold War echoes, while the Yolons represent imperial overreach, critiquing unchecked technological hubris. Crystals serve as metaphors for hope—persistent across deaths, they accumulate like memories, urging perseverance. The three worlds (likely representing colonized frontiers, alien territories, and Earth’s remnants) escalate this arc: early levels evoke scavenging survival, mid-game ramps up rebellion, and finales culminate in liberation. Multiplayer shifts to pure territorial conflict, trapping foes in trails as a microcosm of interstellar conquest. Flaws abound—no deep character arcs or branching paths—but the storyline’s efficiency amplifies its punch, turning arcade runs into a fable of human tenacity.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Startron‘s core loop is a masterful deconstruction of light-cycle mechanics, wrapped in arcade action. You pilot a spaceship across a two-dimensional plane (rendered in 3D perspective with a fixed camera trailing behind), leaving an indestructible trail that acts as both shield and hazard—collide with it, an enemy’s, or the boundary, and you crash, resetting your trail but retaining collected crystals. The objective? Hunt colored crystals scattered across procedurally feel-like arenas, powering up your score and unlocking progression. Single-player spans three worlds with 24 levels, each escalating in size, crystal density, and hazards like moving obstacles or AI pursuers simulating Yolon drones.

Combat emerges organically: no guns, but strategic trail-laying traps enemies, forcing dodges that expose vulnerabilities. In multiplayer (1-8 offline via LAN, 2-8 online—ambitious for 2000 freeware), the goal flips to elimination, with players weaving deadly webs to box in opponents. An optional top-down 2D view toggles for tactical oversight, a smart nod to accessibility. Character progression is light: crystals persist post-death, building toward level clears and perhaps ship upgrades (implied in lore but mechanically basic). The UI is minimalist—keyboard-driven (WASD or arrows for movement, space for boost?), with a HUD tracking crystals, lives, and timers—clean but unforgiving, lacking tutorials that could’ve eased newcomers.

Innovations shine in persistence: deaths aren’t total failures, encouraging risky plays for high-reward crystal grabs. Flaws include repetitive level design (arenas feel grid-like, echoing Tron but lacking variety) and finicky controls on era hardware, where input lag could doom precision maneuvers. Multiplayer latency over dial-up internet was a gamble, yet it fostered emergent chaos. Overall, the systems cohere into tense, replayable loops, rewarding spatial awareness over reflexes alone—a flawed but innovative evolution of arcade purity.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Startron‘s universe is a desolate yet vibrant sci-fi tapestry, blending post-apocalyptic grit with neon futurism. The setting spans colonized outposts, Yolon-infested voids, and Earth’s scorched ruins—evident in level themes where arenas morph from starry expanses to debris-littered grids. World-building is lore-driven: crystals pulse as remnants of Terran tech, trails mimic energy wakes from warp drives, and crashes evoke hull breaches. This creates an atmosphere of fragile hope amid cosmic ruin, where every level feels like a skirmish in humanity’s reclamation.

Visually, the art direction punches above its indie weight. 3D models by Lukas Stattin give ships angular, Tron-esque sleekness—glowing hulls in primary colors against wireframe arenas. The fixed third-person camera immerses you in velocity, with trails rendering as luminous barriers that build claustrophobia. Textures are basic (low-poly polygons standard for 2000), but particle effects for explosions and crystal pickups add flair. The optional 2D top-down view strips to essentials, prioritizing strategy over spectacle. Drawbacks? Repetition breeds visual fatigue, and no dynamic lighting limits depth.

Sound design, courtesy of Robert Glashuettner, elevates the experience with a synth-heavy soundtrack—pulsing electronic beats that evoke Tron‘s arcade pulse, syncing to acceleration and crashes for rhythmic tension. SFX are crisp: whooshes for trails, crystalline chimes for pickups, and explosive booms for deaths. No voice work, but ambient hums simulate spaceship isolation, fostering immersion. Together, these elements craft a lean, atmospheric package—art and sound not revolutionizing the era, but synergizing to make Startron‘s arenas feel alive and perilous, amplifying the thrill of narrow escapes.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Startron garnered modest attention in freeware circles, with critical reception averaging 60% from two reviews on MobyGames. GameHippo.com praised it effusively (90/100) in 2001, lauding its fusion of Pac-Man collection and Tron trails as “ingredients from several classic arcade games,” highlighting addictive multiplayer. Conversely, Germany’s PC Player dismissed the single-player as “quickly tiresome” (30/100), valuing only the multiplayer variant—a fair critique of its arcade brevity. Player scores averaged 3/5 from one rating, reflecting niche appeal. Commercially, as public domain freeware, it saw no sales but spread via downloads on sites like Caiman, amassing a small cult following in LAN parties.

Over two decades, Startron‘s reputation has evolved from forgotten curiosity to preservationist darling. Archived on Internet Archive since 2016, it’s celebrated in retro communities for embodying early indie ethos—raw, unpolished, and innovative. Its legacy echoes in the light-cycle genre: games like Polytron’s Fez (2012) or modern takes like Tron: Evolution (2010) borrow trail mechanics, while freeware revivals nod to its multiplayer DNA. Industry influence is subtler; it prefigured indie arcade resurgences on itch.io and Steam, inspiring devs to blend nostalgia with sci-fi narratives. Yet, its broken website trivia underscores ephemerality—without emulation pushes, it risks vanishing. Today, amid remakes of Tron, Startron deserves rediscovery as a bridge between arcade roots and digital distribution’s dawn.

Conclusion

Startron distills the essence of 2000s indie gaming into a taut package: elegant trail-laying mechanics, a resonant sci-fi tale of defiance, and communal multiplayer joy, all undercut by repetition and era limitations. From Sabadello’s solo vision to Glashuettner’s lore-infused soundscape, it exemplifies resourceful creativity in a blockbuster-dominated landscape. While not a masterpiece, its persistence—crystals enduring crashes—mirrors its own survival. In video game history, Startron claims a niche as a freeware pioneer, a must-play for arcade aficionados and retro historians. Verdict: 7.5/10—a sparkling relic worth firing up on a virtual machine, reminding us that even in digital ashes, innovation can ignite new worlds.