- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Interplay Productions, Inc.

- Developer: Tribal Dreams

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 67/100

Description

Of Light and Darkness: The Prophecy is a 1998 first-person adventure game set in a sci-fi/futuristic world at the end of the millennium, where the fate of humanity teeters on the brink of apocalypse. Players must collect colored orbs and artifacts to redeem evil spirits by solving puzzles that involve identifying each spirit’s associated sin, representative artifact, and corresponding color, navigating real-time challenges through sin-themed rooms to thwart impending doom.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Of Light and Darkness: The Prophecy

PC

Of Light and Darkness: The Prophecy Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (58/100): Imagine combining the realtime elements of The Last Express and the graphic style of Zork Nemesis with the play mechanics of Myst. It’s an intriguing idea, but not one that will keep anyone sitting in front of a computer for more than a day or two.

metacritic.com (58/100): At its best, Of Light and Darkness will remind you of the classic TV series The Prisoner. It can be artfully disorienting and promise hidden depths of meaning.

myabandonware.com (90/100): It lives up to its mysterious, surreal and fantastic promises.

mobygames.com (64/100): Sparkling but flawed gem.

Of Light and Darkness: The Prophecy: Review

Introduction

In the shadow of Y2K fears and millennial anxieties, Of Light and Darkness: The Prophecy emerged as a bold, surreal fever dream from Interplay Entertainment, a publisher riding high on RPG successes like Fallout but eager to dip into experimental adventures. Released in 1998 for Windows, this first-person point-and-click title promised an apocalyptic odyssey blending redemption, sin, and end-times prophecy into a real-time puzzle gauntlet. As the Chosen One, players must thwart Gar Hob, the Dark Lord of the Seventh Millennium, by redeeming the tormented souls of history’s greatest villains—from Caligula to modern-day killers—before a doomsday clock ticks to zero. Drawing from Nostradamus, the Book of Revelations, and global mythologies, the game weaves a tapestry of light versus darkness that feels both prophetic and profoundly weird.

What sets Of Light and Darkness apart in the late-90s adventure landscape—dominated by static puzzle epics like Myst and Riven—is its audacious fusion of real-time urgency, Hollywood voice talent (James Woods as the snarling Gar Hob, Lolita Davidovich as the ethereal Angel Gemini), and surreal art by French painter Gil Bruvel. Yet, for all its atmospheric ambition, the game stumbles into repetition and frustration, turning what could have been a transcendent experience into a polarizing curio. My thesis: Of Light and Darkness stands as a flawed masterpiece of artistic intent over mechanical polish, a testament to the era’s experimental spirit that rewards patient historians but alienates casual players, influencing niche surreal adventures while fading into obscurity.

Development History & Context

The late 1990s were a golden age for CD-ROM adventures, with pre-rendered visuals and FMV pushing the boundaries of what games could evoke. Interplay, founded by Brian Fargo in 1983 and known for innovative titles like The Bard’s Tale and Wasteland, sought to capitalize on this trend amid a shifting industry. The company was diversifying beyond RPGs, funding experimental projects to compete with Sierra and LucasArts. Of Light and Darkness was one such venture, born from millennial hysteria—the Y2K bug, apocalyptic cults, and fears of technological Armageddon—making it a timely reflection of cultural unease.

Development began with Heartland Enterprises, a now-defunct UK studio in Harrogate, North Yorkshire, using their proprietary EDEN engine. Heartland’s vision emphasized surreal, psychedelic worlds, but tensions arose when Interplay halted payments, pulling the plug mid-production. Surviving promo assets from Heartland (visible in archival YouTube footage) show a more ethereal, less polished prototype, hinting at what might have been a dreamier affair. Interplay reassigned the project to Tribal Dreams, a California-based team of SGI graphics wizards assembled by Fargo. Directed by David Riordan (Voyeur), produced by Brian F. Christian, and designed by puzzle maestro Cliff Johnson (The Fool’s Errand), the core team blended narrative expertise with technical prowess.

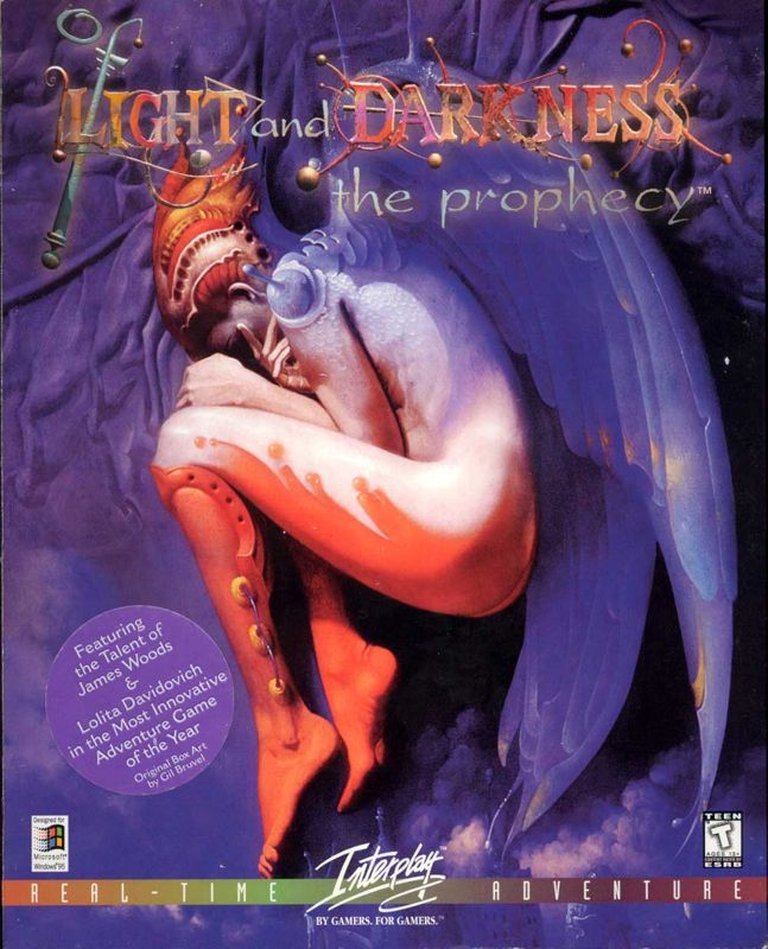

Key contributors included writer Kenneth Melville (Sewer Shark), programmer Eric Whelpley, lead artist Wes Burian, and art director Todd J. Camasta. The surreal visuals were helmed by Gil Bruvel, an award-winning French surrealist whose oil paintings infused the game with dreamlike distortions—think Salvador Dalí meets carnival grotesquerie. Bruvel’s nude fetal-position artwork for the box (featuring Angel Gemini) sparked controversy; retailers like Costco refused to stock it, deeming it too provocative compared to Tomb Raider‘s Lara Croft. Interplay’s VP of sales, Kim Motika, decried the hypocrisy, but internal admissions suggested the ad campaign alienated family-oriented chains.

Technological constraints of 1998 shaped the game profoundly. Running on Windows 95/98 with Pentium 133 MHz minimum specs, no hardware acceleration, and 16 MB RAM, it relied on pre-rendered 3D via SGI’s 3Di engine and Lightwave for motion-captured animations (Davidovich’s Angel sequences). FMV cutscenes and voice acting demanded three CDs, with no mid-level swaps—a rarity for the era. The game debuted at E3 1996 and 1997, generating buzz for its Hollywood flair, but ballooning costs (fueled by celebrity talent and Bruvel’s custom art) contributed to its commercial doom. Released April 1, 1998 (NA) and later in Europe, it arrived in a saturated market, squeezed between Blade Runner (1997) and The Last Express (1997), both more narrative-driven. Interplay’s financial woes—exacerbated by flops like this—foreshadowed its 2000s decline, but Of Light and Darkness endures as a snapshot of bold, budget-strapped innovation.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Of Light and Darkness is a metaphysical courtroom drama masquerading as an apocalypse thriller, pitting the forces of light against eternal darkness in a cyclical battle every millennium. The player awakens as the unnamed Chosen One in Studio M’Fer—a dimly lit, lava-lamp-adorned radio booth where the Millennium Fakers (MF’ers), an invisible jury of cosmic judges, convene. Voiced with gravitas (Valeri Ross as the Judge, William Utay as the Bailiff), they indict Gar Hob (James Woods’ gravelly menace) for unleashing 51 damned souls to trigger seven biblical catastrophes: Pollution, Radiation, Flood, Plague, War, Earth Shifts, and Poisoned Air. These sins manifest in the Village of the Damned, a limbo between heaven and hell, where apparitions—floating masks of historical villains—wander, depositing sin-linked artifacts into disaster rooms to accelerate doomsday.

The plot unfolds across three escalating levels, each a randomized rematch where redeemed souls respawn, symbolizing humanity’s recurring flaws. Players must deduce each apparition’s deadly sin (from the seven: Sloth/Accidie, Anger, Avarice/Greed, Envy, Gluttony, Lust, Pride) using the Book of the Damned manual, which profiles 32 real and mythical figures like Caligula (Pride, via a sword artifact), Ivan the Terrible (Anger), Cain (Envy), and even modern ones like John Wayne Gacy (Lust). Clues emerge from artifact victim testimonies at the Clock of Judgment, apparition taunts, and colored stars in the Mask Room grouping three souls by redemption hue (blue, red, etc.). Successful redemptions trigger hilarious FMV trials: the Bailiff calls the soul, the Judge demands a confession, and the apparition quips wittily—e.g., Caligula’s defiant “I was emperor!”—before addressing Gar Hob’s fury. Woods’ performance shines here, channeling Disney’s Hades with sardonic glee.

Interwoven is Angel Gemini’s subplot: a Vegas showgirl turned prophetess (Davidovich’s luminous motion-capture), shot mid-revelation after slaying her dark-hearted lover. Her visions—seated amid blue dolphins, tempted by sins—reveal her as the Vessel of Resolution, tying player fate to hers and Gar’s. The narrative culminates in the Dark Isle confrontation, solving pyramid puzzles to free her and banish Gar, yielding multiple endings based on performance—one resets the cycle for the Eighth Millennium, underscoring themes of inevitable recurrence.

Thematically, the game grapples with millennial dread, redemption’s futility, and sin’s universality, drawing from global lore (Quechua god-kings to Marie Antoinette) for a multicultural critique of evil. Dialogue crackles with clever, tongue-in-cheek humor—apparitions’ excuses evoke Clue meets The Twilight Zone—but pretension lurks: sins are abstract, clues opaque, demanding manual consultation. This opacity critiques blind faith in prophecy, mirroring Y2K paranoia, yet frustrates coherence. Characters like Mad Jackson (Graham Beckel) or The Amazing Zandi (Jacob Witkin) add flavorful cameos, but the story’s surrealism often obscures emotional stakes, prioritizing allegory over empathy. Still, in an era of linear tales, its randomized souls and philosophical loops innovated narrative replayability, influencing later metaphysical adventures like Kentucky Route Zero.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Of Light and Darkness innovates on the point-and-click formula by injecting real-time pressure into a puzzle-adventure shell, creating a frantic “exorcism sim” that demands memory, speed, and strategy over leisurely exploration. Core loops revolve around three levels of the Village: scout for randomized colored orbs (redemption tools), snatch artifacts from disaster rooms (activating aggressive apparitions), deduce sins via manual/clues, and redeem in sin rooms before the Judgment Clock depletes (15-20 minutes per level, extendable by white light blasts or portal shortcuts).

Inventory is minimalist—only orbs, trans-portals (pyramid teleporters dropped on use), artifacts, and keys—accessed via right-click hold, left-select, spacebar activation. Movement is node-based: cursor turns to harlequin shoes for fluid, animated pans (360° rotation, occasional up/down views), evoking a rollercoaster through surreal spaces. No complex verb commands; interactions are intuitive grabs or spacebar uses, but real-time pursuit adds tension—apparitions stalk artifact thieves, teleporting players or cursing them (paralysis in later levels requires cures). Dark Lords (e.g., skulls with colored eyes) escalate: they steal items, block paths, or lock rooms, forcing adaptive routing.

Progression ties to redemption: each soul saved unlocks areas, but respawns per level simulate Gar’s “second chances,” randomizing orb/mask colors while fixing sins/artifacts for consistency. Free Tour mode (post-level) scouts layouts, revealing lock requirements without apparitions, aiding planning. Customization shuffles souls for replay, and an add-on (Premonitions, 1998) adds practice mini-games. UI is clean but clunky: escape to Game Booth for saves (no in-game hotkeys), gamma/rotation tweaks via F-keys, and password cheats from online puzzles (now defunct).

Flaws abound: repetition grinds early—endless backtracking, trial-and-error deductions (manual essential, frustrating sans it)—and timer punishes hesitation, yielding motion sickness from rapid pans. Puzzles lack variety beyond deduction/chase; no branching dialogues or environmental riddles, just mechanical matching. Compared to Myst‘s static logic, this feels dynamic but shallow, rewarding reflexes over intellect. Yet, innovations like randomization and pursuit AI prefigure action-adventures (The Last Express), though execution falters, making it a bold but uneven system.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Village of the Damned is a phantasmagoric masterpiece, a post-apocalyptic fairground limbo where heaven’s glow clashes with hell’s carnival decay. Gil Bruvel’s 3D environments—pre-rendered in 640×480, 256 colors—pulse with surreal vibrancy: twisted spires house sin rooms (Lust’s erotic murals unsettle teens), disaster hubs spew thematic horrors (Radiation’s crackling Geiger wastes), and the central Clock ticks like a heartbeat. Masks float ethereally, artifacts (swords, skulls) whisper lore, creating a cohesive, immersive nexus. Free Tours reveal layered details—locked doors taunt with hints—building a world that feels alive, oppressive, and prophetic.

Art direction elevates the experience: Bruvel’s surrealism (fetal angels, psychedelic skies) evokes The Prisoner or Twin Peaks, with motion-captured FMVs (Angel’s dolphin-flanked visions) adding cinematic intimacy. Sound design amplifies immersion: Steve Gutheinz and Kenneth Melville’s score blends post-rock dirges, choral wails, and MF’ers jams (e.g., “Mondo Apocalypso” trailer tune), shifting per room—Plague’s moans, War’s drums—for atmospheric dread. Voices are stellar: Woods’ Gar Hob snarls with villainous charm, Davidovich’s Angel whispers redemption, while ensemble (Lois Chiles, Victor Love) infuses trials with wit. Effects—swishing doors, static bursts, apparition howls—blend seamlessly, but the grating female announcer (“One minute remaining!”) jars, underscoring thematic irritation.

Collectively, these elements forge a hypnotic mood: visuals and audio make disasters visceral (Flood’s drowning cries), sins introspective, turning gameplay’s tedium into a trance-like ritual. In 1998 hardware limits, it’s a triumph of artistry, contributing to the game’s cult allure despite mechanical woes.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Of Light and Darkness garnered mixed acclaim, averaging 63% from 23 critics (MobyGames) and 58/100 on Metacritic. Highs included Attack Games’ 90% (“fullpoängare” near-perfect for visuals/story) and Power Unlimited’s 85% (sfeervol, freaky adventure for serious fans). Computer Gaming World (80%) hailed it “fresh, fascinating, mesmerizing,” praising patience-rewarding depth, while Gamezilla (82%) lauded unique ideas, humor, and replayability via randomization. Electric Games (82%) and Techtite (80%) spotlighted surreal art and voice acting, likening redemptions to elevated Clue.

Criticisms centered on repetition and opacity: Game Revolution’s 33% called it “not fun,” with boring puzzles and average graphics; PC Joker (39%) mocked its “krude” esotericism and timer frustration; Quandary’s 20% deemed it “mind-numbingly repetitive” post-mastery. German outlets like PC Games (31%) and GameStar (52%) panned the unintuitive manual reliance and monochromatic dreariness. Player scores averaged 3.2/5 (MobyGames), with Scott Monster’s review capturing the consensus: “sparkling but flawed gem”—great visuals/story, but redundant trial-and-error.

Commercially, it flopped disastrously, burdened by high costs (celebrity VO, custom art) and controversy (box art boycott). Interplay’s woes mounted, contributing to its 2002 sale. Reputation evolved from “pretentious obscurity” to cult curiosity; 2012’s Complex ranked its ending among gaming’s worst (abrupt cycle reset), yet GOG/Steam re-releases (2016) sparked nostalgia. User reviews praise artistry (bloodhawkone: “Forgotten Classic”) but decry tedium (ZwaanME: “Hard to recommend”). Influence is subtle: prefigured surreal real-time adventures (Kentucky Route Zero, The Swapper), inspired indie eschatology (e.g., The Light in the Darkness, 2023), and highlighted adventure pitfalls (manual dependency, timer fatigue). As a Y2K relic, it endures in academic citations (MobyGames notes 1,000+), a polarizing footnote in Interplay’s legacy.

Conclusion

Of Light and Darkness: The Prophecy is a mesmerizing mirage—visually stunning, thematically ambitious, sonically enveloping—yet undermined by repetitive chases, cryptic puzzles, and a timer that turns exploration into endurance. Its development turbulence mirrors the game’s chaotic limbo, birthing a title that captures 1998’s experimental zeal but falters in accessibility. Redeeming 51 souls across randomized levels offers intellectual thrills for puzzle aficionados, bolstered by Woods’ charisma and Bruvel’s visions, but casual players face frustration.

In video game history, it occupies a niche as Interplay’s boldest adventure swing, a commercial casualty that influenced surreal indies while warning of overambition. For historians, it’s essential: a snapshot of millennial dread and artistic risk-taking. Verdict: Play for the atmosphere (7/10), but brace for flaws— a flawed prophecy worth heeding, if only to ponder what light might pierce its darkness.