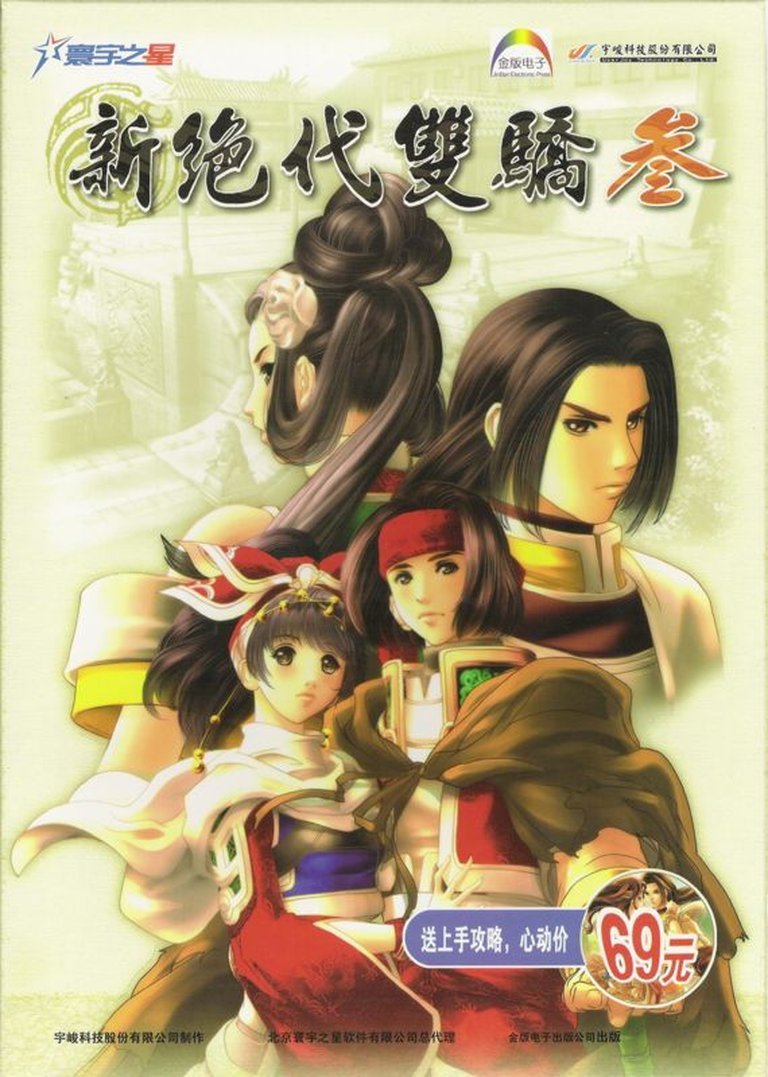

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Beijing Unistar Software Co., Ltd.

- Developer: UserJoy Technology Co., Ltd.

- Genre: Role-playing

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Active Time Battle, Isometric, Random encounters

- Setting: Chinese, Fantasy

Description

Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 is a fantasy RPG set in a Chinese-inspired world, continuing the saga of the twin brothers Jiang Xiaoyu and Hua Wuque, whose family strife leads to tragedy. Eight years after Hua Wuque and his son vanish during a visit to the Chouhuang palace, Jiang Xiaoyu’s sly son Jiang Xia embarks on a quest to find his cousin and reunite the fractured family, only for fate to replay the old drama in an isometric adventure featuring pre-rendered backgrounds, 3D characters, and active time battles reminiscent of Final Fantasy.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3: A Wuxia Legacy Revisited

Introduction

In the shadowed realms of ancient Chinese lore, where twin heroes clash not just with swords but with the inexorable pull of destiny, Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 emerges as a poignant epilogue to a storied saga. Released in February 2003 for Windows, this RPG draws from the well of Gu Long’s iconic wuxia novel series The Legendary Siblings (also known as Twin Heroes), but carves its own path by diverging from direct adaptation. As the third installment in a trilogy that began in 1999, it captures the essence of familial tragedy and martial intrigue that defined its predecessors, blending turn-based tactics with a narrative of fractured bloodlines. For gamers nostalgic for the golden age of isometric RPGs or enthusiasts of East Asian storytelling in video games, Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 (or Twin Heroes III) offers a window into early 2000s Chinese game development—a time when local studios were adapting global influences like Final Fantasy into culturally resonant epics. My thesis: While hampered by technical limitations of its era, Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 stands as a heartfelt continuation of its series, enriching the wuxia genre’s digital legacy through its emphasis on fate-driven drama and tactical depth, though it ultimately falls short of innovating beyond its roots.

Development History & Context

The development of Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 reflects the burgeoning ambitions of Taiwan’s UserJoy Technology Co., Ltd., a studio founded in 1995 and known for producing RPGs that bridged Western mechanics with Eastern narratives. UserJoy, which also worked on titles like UFO Aftermath and later MMORPGs such as Aurora Blade, handled the core development here, infusing the project with a vision to extend the Twin Heroes series beyond its literary origins. Publisher Beijing Unistar Software Co., Ltd., a mainland Chinese firm focused on localizing and distributing PC games during China’s rapid internet boom, ensured the title reached a domestic audience hungry for homegrown content amid strict content regulations.

Released in 2003, the game arrived during a pivotal moment in global gaming. The early 2000s saw RPGs exploding with Japanese imports like Final Fantasy X (2001) and Western open-world experiments like The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (2002), but China’s PC market was still nascent, dominated by pirated copies and a push toward original IP. Technological constraints were stark: Running on Windows 95/98 with a minimum Intel Pentium II processor, 64 MB RAM, and DirectX 8.1a, Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 was designed for modest hardware common in Chinese households. It utilized Direct3D for rendering isometric views, pre-rendered backgrounds to mask hardware limits, and small 3D character models to evoke the era’s hybrid aesthetics—think Diablo II (2000) meets early 3D experiments. Middleware like Bink Video handled cutscenes, allowing for cinematic storytelling without taxing systems.

UserJoy’s vision, as inferred from the series’ progression, was to evolve from 2D roots in the 1999 original to a more dynamic 3D-hybrid in this entry, emphasizing active time battles (ATB) inspired by Square Enix’s systems. However, budget constraints—typical for a mid-tier Chinese studio—meant compromises: No online features, single-player focus, and a reliance on CD-ROM distribution at 8X speeds. In the broader landscape, this game contributed to the “Chinese RPG wave,” alongside contemporaries like Xin Xianjian Qixia Zhuan (2001), signaling how developers were localizing global tropes (e.g., ATB combat) to wuxia themes, fostering a genre that would influence later hits like Genshin Impact. Yet, piracy and limited international export kept it obscure outside Asia, a fate shared by many titles from this period.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its heart, Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 is a tapestry of tragedy, weaving the threads of Gu Long’s wuxia universe into a sequel that prioritizes emotional resonance over strict fidelity. The plot picks up after the “mortal strife” between twin brothers Jiang Xiaoyu and Hua Wuque, resolved in prior games but leaving scars that ripple across generations. Hua Wuque, reclaiming his Jiang lineage, entrusts his son Jiang Yun to the enigmatic chairman of the Chouhuang Palace—a decision born of caution that spirals into loss. Hua’s final visit to the palace marks the brothers’ last encounter; neither he nor young Jiang Yun returns, vanishing into the mists of fate.

Eight years on, Jiang Xiaoyu—ever the relentless seeker—remains haunted by absence. His son, Jiang Xia, embodies a sly, “slightly demonic” inheritance, blending cunning with a familial drive to reunite the bloodline. The protagonist’s quest to find his cousin Jiang Yun unfolds against a backdrop of recurring tragedy: “Fate is not to be stopped, and it plays the old tragedy again.” Unlike the first two games, which hewed closely to Gu Long’s 1966-1969 novel, this entry forges an original tale, exploring post-canon consequences. The narrative unfolds through branching dialogues and key events, emphasizing themes of inherited destiny, the fragility of brotherhood, and the cyclical nature of wuxia vendettas.

Characters are richly archetypal yet nuanced. Jiang Xia, the sly heir, serves as a player avatar whose choices influence alliances, echoing the moral ambiguity of Gu Long’s protagonists—think Hua Wuque’s stoic nobility contrasted with Xiaoyu’s roguish charm, now passed to the next generation. Supporting cast, including palace guardians and shadowy antagonists from the Chouhuang faction, deepen the intrigue; dialogues, delivered in traditional Chinese script with simplified variants for accessibility, brim with poetic flair, laden with idioms like “blood thicker than water” twisted into ironic betrayals. Themes delve into filial piety versus personal ambition, the illusion of control in a fate-ordained world, and the erosion of legacy—profound for a culture steeped in Confucian ideals. Subtle motifs, such as recurring twin imagery and dreamlike sequences (likely via Bink Video), underscore how history repeats, critiquing the wuxia trope of endless feuds. While plot holes arise from its non-canon divergence—e.g., unresolved palace mysteries— the storytelling captivates through emotional beats, making it a thematic triumph in serialized RPG narrative.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 anchors its experience in classic RPG loops, refined for tactical depth in a wuxia framework. Exploration adopts an isometric perspective, blending point-and-click navigation with light puzzle-solving across pre-rendered environments like misty palaces and forested trails. Players control Jiang Xia and recruited allies, scouring maps for clues to the missing kin; random encounters in certain zones heighten tension, while visible enemies in others allow preemptive strikes, adding strategic scouting akin to Fallout‘s hybrid model but simplified for 2003 hardware.

Combat is the game’s crown jewel: An active time battle (ATB) system, directly echoing Final Fantasy‘s gauge-filling mechanics, where characters act in real-time turns based on speed stats. Battles pit parties against foes in isometric arenas, with commands for martial arts combos, qi-based spells, and item use. Turn-based pacing ensures thoughtful decisions—queueing attacks, exploiting elemental weaknesses (fire vs. wind, rooted in wuxia lore)—but the ATB twist injects urgency, preventing stagnation. Party management shines: Recruitable NPCs like sly informants or stoic warriors customize builds, with character progression via experience points unlocking skill trees for dual-wielding swords or illusionary dodges, reflecting Gu Long’s fluid fight choreography.

However, flaws mar the systems. The UI, mouse-and-keyboard driven, feels clunky on 800×600 resolution: Tiny icons and dense menus demand pixel-hunting, a relic of era constraints. Progression is linear, with grinding for levels in random battles feeling rote, and no autosave exacerbates CD-ROM load times. Innovations include “fate events”—choice-driven branches altering companion loyalty and plot forks—but they’re underutilized, lacking the replayability of contemporaries like Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (2003). Overall, the loops deliver satisfying tactical wuxia skirmishes, but technical jank and limited scope hold it back from greatness.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world is a evocative recreation of a fantastical ancient China, steeped in wuxia aesthetics: Towering pagodas of the Chouhuang Palace, fog-shrouded bamboo groves, and hidden sects evoke Gu Long’s blend of myth and martial realism. Exploration fosters immersion through interconnected hubs—riverside villages to imperial courts—where lore drips via environmental storytelling, like ancestral scrolls hinting at twin curses. Atmosphere builds dread through fate’s shadow; dynamic weather (rain-slicked duels) and day-night cycles subtly influence encounters, contributing to a sense of inexorable progression.

Visually, pre-rendered backgrounds provide painterly detail—silk scrolls come to life with lush inks and golds—while small 3D models animate fluidly in combat, their exaggerated poses capturing wuxia grace (leaping slashes, qi auras). The isometric view enhances tactical readability but constrains openness, with full-screen 800×600 limiting grandeur; textures pop on period hardware, though aliasing creeps in. Art direction honors Chinese heritage: Ornate UI motifs, like dragon engravings, and character designs drawing from novel illustrations (flowing robes, stern gazes) create cultural authenticity.

Sound design, though sparse in documentation, leans on era tropes: MIDI-inspired orchestral scores with erhu strings and pipa plucks swell during battles, evoking melancholy destiny. Voice acting—likely in Mandarin—adds gravitas to dialogues, with Bink cutscenes featuring dramatic readings. SFX, from sword clashes to ethereal qi hums, enhance immersion, but the lack of dynamic audio (e.g., no adaptive music) feels dated. Collectively, these elements forge a cohesive, atmospheric wuxia realm that punches above its tech weight, immersing players in a world where every vista whispers of tragic legacies.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 2003 launch, Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 garnered modest attention in Chinese gaming circles, praised for narrative continuity but critiqued for uninnovative mechanics. No major critic reviews exist in English databases, but player ratings on MobyGames average 3.4/5 from two votes—suggesting niche appeal among series fans, tempered by technical gripes. Commercially, as a CD-ROM title from Beijing Unistar, it likely sold steadily in Asia’s PC market, bolstered by the Twin Heroes brand, but piracy diluted profits. Internationally, obscurity reigned; Western sites like Kotaku note its Gu Long roots but offer no analysis, while Giant Bomb’s barren review page underscores its cult status.

Over two decades, reputation has evolved into quiet reverence. Collected by only five MobyGames users, it’s a hidden gem for wuxia RPG historians, influencing later Chinese titles like The Sword and Fairy remakes by emphasizing ATB in fantasy settings. Its legacy lies in pioneering digital wuxia serialization—paving for mobile adaptations and MMOs—while highlighting 2000s constraints that spurred innovation elsewhere. Though not a blockbuster, it endures as a testament to UserJoy’s vision, subtly shaping the industry’s embrace of literary IPs in interactive media.

Conclusion

Xin Juedai Shuangjiao 3 masterfully extends its series’ tragic arc, blending heartfelt wuxia narrative with tactical ATB combat and evocative Chinese-inspired world-building, all within the humble confines of 2003 PC tech. Strengths in thematic depth and cultural fidelity shine, but clunky UI, linear progression, and era-limited visuals prevent it from transcending its niche. As a bridge between literature and gaming in Asia’s rising industry, it earns a solid place in RPG history—not as a revolutionary force like Final Fantasy VII, but as a poignant chapter in the digital adaptation of Gu Long’s enduring twins. Recommended for wuxia aficionados seeking nostalgic tactical depth; 7.5/10— a worthy, if flawed, finale to a legendary saga.