- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: MarBit

- Developer: MarBit

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Tile matching puzzle

Description

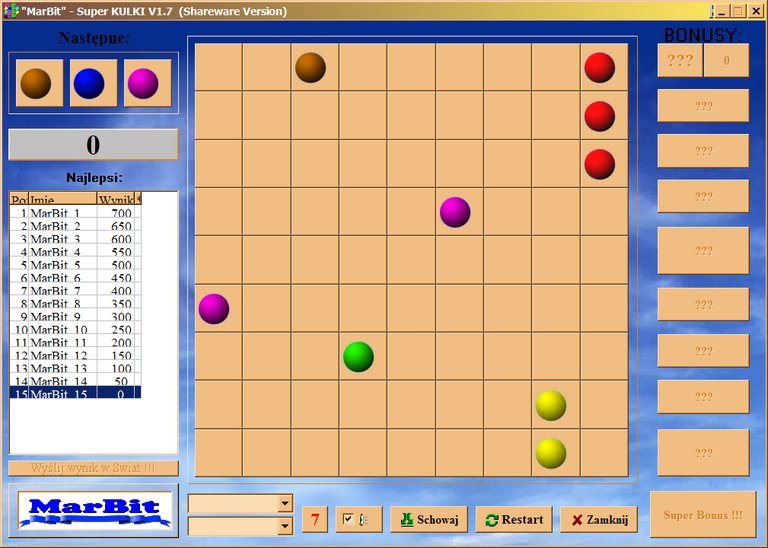

Super Balls is a classic tile-matching puzzle game inspired by the Color Lines concept, set on a grid board where players strategically move colorful marbles to form rows, columns, or diagonals of at least five identical colors. Each move allows repositioning a marble along a clear path, followed by the random appearance of three new marbles, with successful lines vanishing for points and bonus moves, while forming larger groups unlocks powerful bonuses ranging from random effects to enhanced abilities.

Gameplay Videos

Reviews & Reception

sharewarejunkies.com : Another of the type of puzzle games where you move balls into rows of five or more, with unique bonus buttons but lacking clear directions.

Super Balls: Review

Introduction

In the vast tapestry of video game history, few titles evoke the quiet thrill of intellectual conquest quite like Super Balls, a 2000 Windows shareware puzzle that distills the addictive essence of tile-matching into a deceptively simple grid of colorful marbles. Released at the dawn of the new millennium, when personal computing was exploding with casual games that promised quick dopamine hits amid the rise of browser-based entertainment, Super Balls stands as a humble yet enduring artifact of the shareware era. Drawing from the foundational Color Lines mechanic pioneered in the early 1990s, it challenges players to orchestrate chaos into order, one strategic move at a time. As a game journalist and historian with decades of dissecting digital pastimes, I argue that Super Balls transcends its modest origins to embody the pure, unadorned joy of puzzle design—proving that brilliance need not rely on spectacle, but on the elegant interplay of foresight, luck, and satisfaction in clearing the board.

Development History & Context

Super Balls, also known internationally as Super Kulki, emerged from the small Polish studio MarBit, a outfit active from the early 1990s through the early 2000s, specializing in accessible shareware titles for the burgeoning PC market. Founded amid the post-Communist economic liberalization in Poland, MarBit represented the grassroots ingenuity of Eastern European developers who leveraged affordable programming tools to compete in the global software scene. The game’s primary architect was Artur Majtczak (credited as “Arczi”), a solo developer whose vision was to refine and expand upon the Color Lines formula—a Russian-origin puzzle mechanic that had captivated players since its 1992 debut on MS-DOS systems via games like Color Lines by Oleg Delyagin.

The year 2000 placed Super Balls in a pivotal gaming landscape: Windows 95/98 dominated desktops, shareware distribution via floppy disks, CDs, and early internet downloads was king, and the industry was shifting from arcade ports to native PC experiences. Technological constraints were minimal for a 2D puzzle—requiring only basic DirectX support for smooth mouse input—but MarBit’s implementation highlighted the era’s DIY ethos. With an installed size of just under 500KB (version 1.4), it was lightweight enough for dial-up era machines, reflecting the shareware model’s emphasis on low barriers to entry. Priced at $12 for registration, it followed the classic freemium tease: full play with nagging reminders to buy, a tactic common in titles from CNET’s Download.com or Shareware Junkies.

Majtczak’s creative intent, inferred from the game’s evolution (an older version archived on MarBit’s site via the Wayback Machine), was to inject replayability into a saturated genre. Amid competitors like Magic Balls (1994, Amiga) and Rainbow Balls (1995, Windows), Super Balls arrived as a variant in the “Color Lines” group, adapting the core loop for solo mouse-driven play. The Polish development context added a layer of cultural resilience; MarBit’s output, including bundled CDs with demos like Delfin Willy, catered to a market hungry for affordable entertainment in an age before Steam’s dominance. This era’s gaming scene was fragmented—dominated by giants like id Software’s Quake sequels and Blizzard’s StarCraft—yet niches like puzzles thrived on sites like MobyGames, where Super Balls would later be cataloged in 2018 by contributor Havoc Crow, underscoring its underground persistence.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Super Balls eschews traditional storytelling for an abstract, emergent narrative woven through gameplay—a hallmark of pure puzzle games that prioritize mechanical poetry over scripted drama. There is no plot, no protagonists, and no dialogue; instead, the “story” unfolds as a silent battle against entropy on a 9×9 grid (the standard Color Lines board size). Players inherit a nascent chaos: scattered marbles of vibrant hues—reds, blues, greens, yellows, and purples—appearing in random trios after each move, threatening to overwhelm the board like an encroaching digital clutter.

Thematically, Super Balls explores order from disorder, a motif resonant with philosophical puzzles from Tetris to Dr. Mario. Each marble represents potential: a red orb might be a pawn in a grand diagonal alignment, but poor placement dooms it to isolation. The absence of characters amplifies this introspection; you’re the unseen strategist, imposing structure on randomness. Dialogue is nil, save for the shareware nags—pop-up blurbs in English (after initial Polish prompts) urging registration after 10 seconds of inactivity, which ironically underscore themes of impermanence and interruption. These serve as meta-narrative intrusions, reminding players of the game’s commercial reality in an era of freeware abundance.

Deeper analysis reveals undertones of risk and reward. Bonuses for lines of six or more evoke a gambler’s thrill: the “random effect” bonus, a wildcard with good (e.g., clearing spaces) or bad (e.g., spawning extras) outcomes, mirrors life’s unpredictability. Larger clears unlock escalating perks—immediate activations for instant gratification, savable ones for tactical depth—symbolizing accumulated wisdom. In a post-Cold War context, Majtczak’s Polish roots might infuse subtle resilience; the game’s persistence against board-filling doom parallels Eastern Europe’s navigated transitions. Ultimately, the narrative arc is player-driven: from tentative probes to masterful cascades, culminating in high-score triumphs or humiliating restarts. It’s a meditation on patience and foresight, where themes of harmony (aligned colors vanishing in satisfying pops) contrast the void of failure, making every session a micro-epic of cognitive triumph.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Super Balls distills tile-matching into a taut, unforgiving loop that rewards spatial intelligence while punishing hesitation, building on Color Lines‘ foundation with subtle innovations. The core board is a 9×9 grid, starting partially populated; your objective is endless survival, scoring points until the board fills—a “game over” triggered by no valid moves amid 15+ marbles. Each turn grants one relocation: select a marble and drag it to an empty adjacent square via free path (no blocking orbs), adhering to point-and-click mouse interface for precise, intuitive control.

Post-move, three new marbles spawn randomly, injecting peril—colors match the palette of five to seven hues, forcing constant adaptation. Success hinges on forming horizontal, vertical, or diagonal lines of five or more identical colors; upon alignment, they vanish with a point bonus (scaling by length) and an extra turn, creating chain-reaction potential for high scores. This loop—plan, move, spawn, clear—escalates tension as the board densifies, demanding foresight: a single misplacement can block future paths, turning abundance into impasse.

Innovations shine in the bonus system, a layer absent in vanilla Color Lines. Clearing six yields a “random effect” token, activatable for unpredictable outcomes (e.g., bomb clears or marble shuffles—good or bad, per source ambiguity). Seven or more unlocks superior bonuses: some auto-activate (like space creators), others queue on a right-side panel as clickable icons. The shareware review notes these “bonus buttons” altering upcoming spawns—e.g., forcing different colors—adding strategic depth; hit one mid-game to manipulate the RNG, turning luck into leverage. A high-score tracker on the left tallies points, while “restart” ends sessions abruptly, emphasizing roguelike restarts over saves.

Flaws emerge in UI simplicity: no tutorials (directions limited to registration prompts), leading to stumbling discovery. Mouse-only input suits the era but lacks modern accessibility (e.g., no keyboard shortcuts). Progression is score-based, not leveled, fostering replayability via personal bests. Overall, the systems cohere into addictive elegance—innovative bonuses mitigate Color Lines‘ frustration, yet the free-path rule enforces tactical purity, making Super Balls a masterclass in constrained creativity.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Super Balls‘ world is a minimalist abstraction: a stark 9×9 grid floating in digital void, where colorful marbles serve as the sole inhabitants. No lore-rich settings or expansive lore—it’s a pure puzzle plane, evoking the clinical labs of The Incredible Machine or the void of Lines. Atmosphere builds through progression: early boards feel open and hopeful, like a blank canvas; later clutter evokes claustrophobic tension, the grid a battlefield of encroaching marbles. This binary evolution—from sparse potential to jammed despair—crafts immersion via implication, the player’s mind filling narrative gaps.

Visual direction is era-appropriate austerity: Windows-native graphics with bold, primary-colored spheres (glossy 2D sprites, per MobyGames specs) against a plain backdrop, optimized for 800×600 resolutions. No animations beyond basic pops for clears, yet the palette’s vibrancy—crisp reds against teal empties—pops on CRT monitors, contributing to hypnotic focus. Art supports accessibility, with clear color differentiation aiding color-blind play marginally, though lacks modern contrasts.

Sound design is equally spartan: subtle clicks for moves, satisfying chimes or whooshes for clears (inferred from genre norms, as sources omit specifics), and silence otherwise. No soundtrack—perhaps a faint ambient hum in registered versions—keeps distraction low, enhancing the zen-like trance. Shareware nags disrupt with beeps, but overall, audio reinforces themes of quiet strategy. These elements coalesce into an experience of purified tension: visuals and sounds as unobtrusive frames, letting mechanics shine, much like Minesweeper‘s blank slate. In a bombastic 2000 landscape, this restraint fosters timeless intimacy, the grid’s subtle shifts more evocative than any rendered vista.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 2000 shareware release, Super Balls flew under the radar, emblematic of the era’s deluge of indie puzzles. Critical reception was scant; MobyGames lists no formal reviews, with an unranked Moby Score and a lone player rating of 3.6/5 (from one anonymous vote, no text). Shareware Junkies’ 2000 review by Stormy Strock praised its logical depth but dinged absent directions and nag screens, scoring it neutrally on user-friendliness and graphics. Commercially, it likely sold modestly via downloads and CDs (bundled in Polish magazine compilations per Archive.org), aligning with MarBit’s niche output—$12 registrations sustaining a small operation amid free alternatives.

Over time, reputation has warmed through nostalgia. Added to MobyGames in 2018 and last updated in 2023, it’s grouped with Color Lines variants, collected by three players, underscoring cult endurance. No blockbuster sales, but its influence ripples subtly: mechanics echo in modern match-3s like Candy Crush Saga (2012), where line-clearing and spawns evolved into monetized loops. Variants like Magic Balls (2021 remake) and Rainbow Balls cite Color Lines lineage, with Super Balls‘ bonuses prefiguring power-ups in Bejeweled. In industry terms, it exemplifies shareware’s democratization—paving for itch.io indies—while Polish devs like Majtczak influenced later Eastern European hits (e.g., CD Projekt RED’s roots in accessible gaming). Legacy-wise, it’s a preserved relic: archived on Internet Archive, a testament to puzzles’ shelf-life, influencing casual mobile titles like Jumping Balls! (2016) in spirit if not direct credit.

Conclusion

Synthesizing its unpretentious design, Super Balls emerges as a understated masterpiece of puzzle minimalism—a shareware survivor that captures the era’s ingenuity while offering timeless strategic depth. From MarBit’s humble origins to its bonus-laden evolutions of Color Lines, it masterfully balances accessibility with challenge, though UI quibbles and narrative voids temper its polish. In video game history, it claims a niche as an evolutionary link in tile-matching’s chain, influencing casual gaming’s addictive core without fanfare. Verdict: Essential for puzzle aficionados, a solid 8/10—play it today via emulators to appreciate how simple spheres can spark profound engagement.