- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: PLAY Sp. z o.o.

- Developer: Mad Hog Games

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Fighting

- Setting: Europe

- Average Score: 52/100

Description

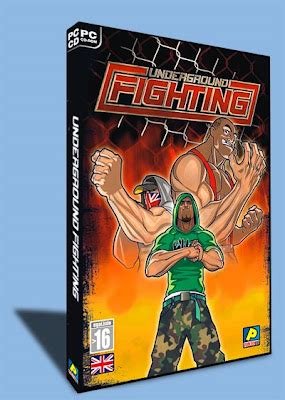

Underground Fighting is a straightforward one-on-one fighting game set in Europe, developed by Mad Hog Games and released in 2007. Players choose from twelve different characters and battle across six locations using dozens of weapons. The game features two primary modes: a Story mode, where players progress through a series of fights to ultimately challenge a mysterious underground fighting master, and a Quick Fight mode for immediate skirmishes against AI or another player.

Gameplay Videos

Underground Fighting Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamepressure.com (52/100): Underground Fighting takes you in the world of illegal fights and dirty alleys where no sane person dare to tread.

mobygames.com : Underground Fighting is a simple one on one fighting game that includes twelve characters, six locations, and dozens of weapons.

Underground Fighting: A Forgotten Relic of Poland’s Fighting Game Foray

In the vast, shadowy archives of gaming history, nestled between the blockbuster hits and the infamous failures, lie titles like Underground Fighting. It is a game that exists not as a landmark, but as a curious footnote—a brief, gritty echo from a small Polish studio attempting to carve its name into the competitive world of 3D brawlers. This is not a review of a masterpiece, but an archaeological dig into a forgotten artifact, an examination of ambition constrained by reality, and a look at the humble origins of developers who would later shape some of the industry’s biggest titles.

Introduction: A Fistful of Obscurity

To review Underground Fighting is to review a ghost. Released in January 2007 by Polish studio Mad Hog Games and publisher PLAY Sp. z o.o., it arrived with no fanfare and departed just as quietly. It is a game that has left almost no cultural footprint, with no critic reviews on Metacritic and a mere handful of user impressions scattered across abandonware sites. Its legacy is not one of influence or acclaim, but of being a fascinating stepping stone. This review posits that Underground Fighting is a profoundly average and technically limited fighting game, yet it remains an essential piece of trivia for its role as the embryonic proving ground for talent that would later define the brutal first-person melee combat of games like Dead Island and Dying Light.

Development History & Context: The Polish Garage Band of Game Dev

The story of Underground Fighting is one of modest means and big dreams. In the mid-2000s, the global gaming landscape was dominated by highly polished, multi-million dollar franchises. Meanwhile, in Poland, a burgeoning development scene was still finding its feet. Mad Hog Games was a small studio, and the credits for Underground Fighting read like a classic indie project: a core team of multi-talented developers wearing every hat imaginable.

The vision, as stated, was simple: create a “one on one fighting game that includes twelve characters, six locations, and dozens of weapons.” The technological constraints of the era are evident in the recommended system requirements: a Pentium III 1.8 GHz, 512 MB RAM, and a 128 MB graphics card. This was a game designed for low-end PCs, a strategic move to capture a broader audience in Eastern European markets where cutting-edge hardware was less common.

The development was a collaborative effort led by Tomasz Klin, who served as Lead Programmer, Engine Designer, and effectively the project’s architect. Krystian Granatowski was the other pillar, acting as Lead Graphics Designer, 3D Modeller, Level Designer, and even the artist for the game’s 2D graphics and comics. This lean structure meant that the game’s scope was necessarily limited. It was not meant to compete with Tekken or Virtua Fighter; it was a passion project built on a shoestring budget, a trial by fire for its creators. The fact that key personnel like Klin and animator Michał Czerniec would go on to work on Techland’s biggest titles illustrates that Underground Fighting was less a destination and more a crucial formative experience.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Thin Veneer of Grit

The narrative ambition of Underground Fighting is, frankly, minimal. The provided source material from IMDb, which details a complex plot for a film also named Underground, is a red herring; it has no connection to the game beyond sharing a namesake. The game’s own story mode is described in the barest terms: “the player can take part in a series of fights that leads him to a final fight with a mysterious underground fighting master.”

This is a boilerplate “rise through the ranks” narrative, a threadbare excuse to move from one bout to the next. There is no evidence of the deep character backstories, motivations, or the thematic exploration of violence and desperation seen in the film’s synopsis. The game’s twelve characters, allegedly from “different subcultures,” are defined solely by their visual archetypes—a soldier, a model, a delinquent—devoid of any dialogue or narrative depth. The theme is pure, unadulterated urban grit: illegal fights in dirty alleys and run-down warehouses. It aims for a certain atmospheric realism but lacks the writing or character development to make the player care about the world or its inhabitants. The story exists only as a framework for the combat, a barebones structure that highlights the game’s focus on its mechanics over its plot.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Functional, Flawed, and Forgetful

At its core, Underground Fighting is a simplistic 3D fighter. The gameplay loop is straightforward: choose a character, enter an arena, and defeat your opponent using a combination of basic attacks, kicks, and weaponry.

- Core Combat: The combat system is described as featuring “unique combos,” but given the game’s obscurity and the lack of detailed documentation, these were likely simple, pre-baked strings of attacks rather than a deep, player-driven combo system. The inclusion of “dozens of weapons” adds a layer of environmental chaos, suggesting a brawler-like element where players can pick up objects to gain an advantage.

- Game Modes: The game offers two modes: a linear Story mode culminating in the battle with the mysterious master, and a Quick Fight mode for instant action against AI or a second player. This was standard fare for the genre, providing a minimal amount of content for solo players and a basic versus option for friends.

- Character Progression & UI: There is no mention of any progression system, skill trees, or unlockables. The game appears to be a static experience: you have all characters and arenas available from the start in Quick Fight, and Story mode offers no rewards beyond the satisfaction of completion. The user interface, crafted by Klin, was likely purely functional—a series of menus to select options and little more.

- Innovation and Flaws: The game’s one noted innovation is its “cinematic camera,” which implies dynamic camera angles during fights to add a sense of drama. However, without critical analysis, it’s impossible to know if this was effectively implemented or merely a jarring, disorienting feature. The flaws, however, can be inferred. With a small team and a tight budget, the game undoubtedly suffered from clunky controls, unbalanced fighters, repetitive gameplay, and a lack of the polish that defined its contemporary competitors. It was a game that functioned, but likely failed to excel in any particular area.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic Ambition on a Budget

The world of Underground Fighting is a grimy, low-poly rendition of urban decay. The six locations—described as “urban arenas, full of unclean games”—were likely a series of gritty environments like warehouses, junkyards, and back alleys, designed by Granatowski. The art direction aimed for a realistic, dirty aesthetic to match its theme, but was hamstrung by the technical limitations of its target hardware. Character models, animated by Czerniec, Granatowski, and Klin, were probably stiff and lacking in detail.

The sound design was handled by Michał Ożarowski and Marek Grabowski, with Ożarowski also composing the music. One can imagine a soundtrack of aggressive, looping rock or electronic music to amp up the intensity of the fights, and sound effects of impacts and grunts that served their purpose without being remarkable. The most intriguing artistic element is the mention of “comics” by Granatowski, which might have been used in still-image cutscenes to deliver the minimal story, a clever and cost-effective way to add narrative flair.

Reception & Legacy: The Echo of Silence

The commercial and critical reception of Underground Fighting was virtually nonexistent. It holds no MobyScore, no critic reviews are archived, and user reviews are scarce. The few comments found on abandonware sites are brief; one user simply calls it a “cool game,” a testament to its obscurity rather than its quality. It was a regional release, primarily distributed in Central and Eastern Europe (Czechia, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania), and it seemingly vanished without a trace upon release.

Yet, its legacy is its people, not its product. This is the most significant aspect of Underground Fighting. The game serves as a fascinating origin story for several Polish developers. Tomasz Klin, the lead programmer and engine designer, and Michał Czerniec, an animator, would later be credited on Techland’s major titles: Dead Island, nail’d, and Dying Light. Their work on the combat and animation systems of those acclaimed games—known for their first-person melee brutality—can be seen as the professional evolution of the skills they honed while creating the rudimentary 3D fights of Underground Fighting. The game itself influenced nothing, but the developers it nurtured went on to influence everything in their sphere.

Conclusion: A Verdict of Historical Curiosity

Underground Fighting is not a good game by conventional critical standards. It is, by all available accounts, a generic, technically limited, and ultimately forgettable fighter that was quickly lost to time. It lacks the narrative depth, mechanical polish, and artistic flair to stand alongside the titans of its genre, or even its more competent peers.

However, to dismiss it entirely would be to ignore its true value. As a historical artifact, it is a compelling snapshot of the small-scale, passionate projects that fueled the growth of the Polish game development scene in the 2000s. It is a textbook example of a studio cutting its teeth on a modest project before moving on to bigger things. Its final, definitive verdict is this: Underground Fighting is an unimportant game that was vitally important for the careers of the people who made it. It is a footnote, but a footnote written in the early drafts of some of gaming’s most visceral and successful action titles. For that reason alone, it deserves a small, quiet place in the annals of video game history.