- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: The Code Zone

- Developer: The Code Zone

- Genre: Action, Maze solving

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Strategy

Description

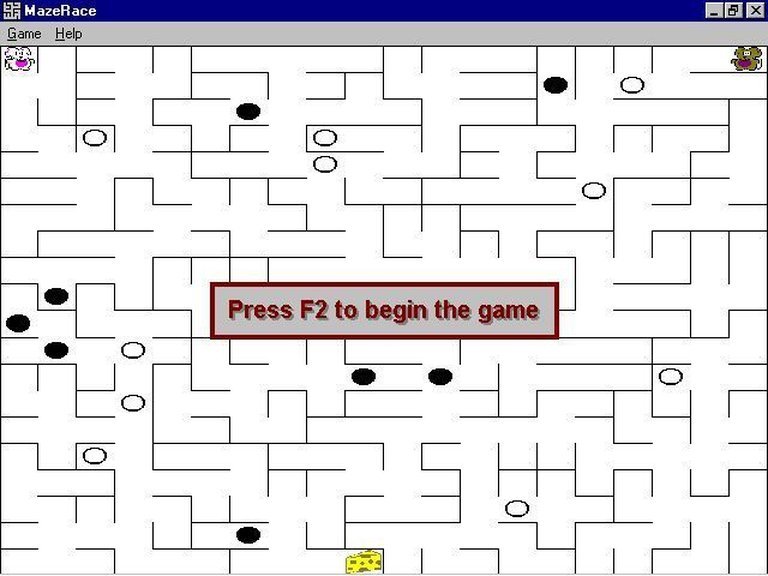

MazeRace is a top-down arcade strategy game released in 2000 where players take control of one of two mice, Hector or Nestor Cheeseman, and race through a randomly generated maze to reach a piece of cheese located at the bottom before their opponent. The maze size is customizable from 5×5 to 50×50, and the game features strategic teleportation spots that can randomly relocate the player or their rival, adding a chaotic element to the race. It supports both single-player and two-player competitive modes with keyboard or joystick controls.

Guides & Walkthroughs

MazeRace: A Forgotten Relic of the Shareware Maze

In the vast, digitized catacombs of video game history, countless titles exist not as celebrated monuments, but as faint echoes—footnotes in a database, entries in a long-forgotten compilation CD. MazeRace, a 2000 Windows release from the enigmatic The Code Zone, is one such echo. It is a game that embodies the very essence of the early PC shareware and budget software scene: functional, straightforward, and almost entirely devoid of the pomp that would come to define the industry. This review seeks to excavate this obscure artifact, not to crown it as a lost classic, but to understand its place as a fascinating, albeit deeply flawed, microcosm of its time.

Development History & Context

The Code Zone: Factory of Fun

To understand MazeRace, one must first understand its creator. The Code Zone was not a studio in the traditional sense, aiming for critical acclaim or blockbuster sales. It operated more like a digital workshop, producing a stable of small, simple games that were bundled and re-bundled into “around twenty different game compilation products.” This was the economic reality for many small developers at the turn of the millennium: survival through volume and licensing, not originality.

The project was helmed by John Hattan (credited under the handle “John ‘FlyMan’ Hattan”), with Shelley Hattan handling the help files. The credits reveal a development process built on borrowed assets and pragmatic tools. The game was “Created Using StarView by Star Division Corporation,” a now-obscure software suite predating Star Division’s acquisition by Sun Microsystems and later Oracle. Its graphics were sourced from “SpriteLib[www.chromewav.com,” a free sprite library, and its MIDI files were “Courtesy [of] Microsoft Corporation,” likely lifted from the ubiquitous sound collections bundled with Windows itself.

This patchwork construction speaks volumes of the technological constraints and the “make-do” ethos of the era. This was not a game built from the ground up with a custom engine; it was assembled from available parts, a digital Frankenstein’s monster designed for functionality over finesse. The development landscape was crowded with such titles, vying for space on store shelves next to cereal boxes in massive, multi-disc compilations with names like “500 Arcade Classics!”

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Epic of Hector and Nestor Cheeseman

To call MazeRace’s narrative “thin” would be a profound overstatement. It possesses a narrative premise so simple it borders on the archetypal. Two mice, Hector and Nestor Cheeseman, are placed in a maze. A piece of cheese awaits. The objective: get there first.

There is no dialogue, no character development, and no lore explaining the bitter rivalry between Hector and Nestor. Are they brothers? Competitors for the affections of a lady mouse? We are given nothing. The narrative exists purely as a mechanical justification for the gameplay. The theme is the pure, unadulterated thrill of the chase, the fundamental joy of spatial competition that underpins everything from children’s games to professional sports. MazeRace strips this concept down to its barest binary form: win or lose. Its thematic depth is that of a chalk line drawn on asphalt; it exists only to mark the start of a race.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Core Loop: Chaos in the Corridors

MazeRace’s gameplay is its most defining and, ironically, most interesting feature. On its surface, it is a straightforward top-down maze race. One or two players navigate a randomly generated labyrinth from a default size of 20×20 tiles, adjustable in increments of five up to a massive 50×50 grid. Players start in opposite corners at the top; the cheese is typically located at the bottom.

The genius twist, and the source of all its strategic chaos, is the introduction of the teleportation spots. Scattered throughout the maze are black and white spots, each color corresponding to one of the two mice. Running over your own colored spot instantly teleports you to a random location within the maze—a high-risk, high-reward gambit to break a deadlock or escape a wrong turn. Running over your opponent’s spot, however, teleports them away, serving as a powerful offensive tool to disrupt their path and seize the lead.

This simple addition transforms the game from a pure test of memorization and reflexes into a tactical battle of positioning and prediction. Do you beeline for the cheese, or do you divert to control the teleportation spots? Do you use your own spot as an emergency reset, knowing it could land you further away? The potential for mind games in two-player mode is significant, a frantic mix of strategy and luck that can lead to thrilling last-second reversals.

However, the mechanics are hamstrung by significant flaws. The control is described as defaulting to the arrow keys, with support for redefinition and joysticks, but the implementation is reportedly basic. The most damning technical note is that the game “is played in a window which cannot be re-sized and has in-game help screens which open in new windows.” This points to a clunky, inflexible user experience, a product that feels more like a programming exercise than a polished commercial product. The UI is an afterthought, and the gameplay systems, while clever, are buried under a layer of technical jank.

World-Building, Art & Sound

An Aesthetic of Asset Flips

The world of MazeRace is a sterile, green-gridded void. The visual direction, courtesy of the pre-made sprites from SpriteLib, is purely functional. The mice are simple pixel-art representations, the cheese is a yellow blob, and the teleport spots are plain black and white circles. There is no atmosphere, no texture, no sense of place beyond the abstract concept of “a maze.” It is the video game equivalent of a graph paper puzzle.

The sound design is equally anonymous, relying on stock MIDI files from Microsoft. These would have been the same generic, tinny tunes heard in a hundred other forgettable shareware titles. They serve only to punctuate the silence, not to enhance the mood or immersion. The overall audiovisual presentation contributes nothing to the experience beyond the bare minimum required to convey information to the player. It is a game that looks and sounds exactly like what it is: a cheaply assembled product from a bundle.

Reception & Legacy

The Silence of the Mice

Perhaps the most telling review of MazeRace is the complete and utter absence of any. As evidenced by the source material, there are no critic reviews on MobyGames, no user reviews on Giant Bomb or Grouvee. It was a game that was released into the world and met with a resonant silence. It was not hated; it was simply not noticed. It sold not as a standalone product but as a single tile in the vast mosaic of a compilation pack, a piece of filler content meant to inflate a box’s “500 Games!” claim.

Its legacy is therefore not one of direct influence—no one cites MazeRace as an inspiration for later maze or racing games. Instead, its legacy is archeological. It is a perfect preserved specimen of a specific type of game from a specific moment in time: the budget/shareware era. It represents a business model and a development philosophy that has all but vanished.

Its most curious legacy is its accidental inspiration for others. The GitHub project by mlni to recreate MazeRace in Clojure/Clojurescript is a form of historical preservation, a testament to the fact that even the most obscure artifacts can spark creativity. The developer notes the original was “long lost,” and their project serves as a digital homage, ensuring the simple, clever mechanic of MazeRace is not entirely forgotten. Other GitHub projects with the same name, like those by malcolmshi123 and Lushenwar, further prove the enduring appeal of the maze-racing concept, even if they are not direct descendants.

Conclusion

Verdict: A Historical Curio, Not a Lost Gem

MazeRace is not a good game by modern or even contemporary standards. It is a technically limited, aesthetically barren, and commercially insignificant product. However, to dismiss it entirely would be to ignore its value as a historical document. It is an impeccably pure example of the content mill that fueled the budget software boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Its sole redeeming quality is a genuinely clever gameplay twist—the strategic teleportation spots—that elevates it slightly above the pure shovelware it was bundled with. This mechanic provides a glimpse of a more thoughtful game buried under layers of compromise.

Ultimately, MazeRace’s place in video game history is not on a podium, but in a case study. It is a reminder that for every landmark title that defines a generation, there are thousands of forgotten games like this: simple, functional, and utterly ephemeral. It is a ghost in the machine, a whisper from an era when the digital frontier was wild, weird, and filled with mice racing for cheese. For historians and enthusiasts, it’s a fascinating dig. For everyone else, it remains exactly what it was always meant to be: a brief diversion on a disc packed with hundreds of others.