- Release Year: 2017

- Platforms: Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Worm Animation LLC

- Developer: Worm Animation LLC

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Music, Puzzle elements, rhythm

- Setting: Futuristic, Post-apocalyptic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 68/100

Description

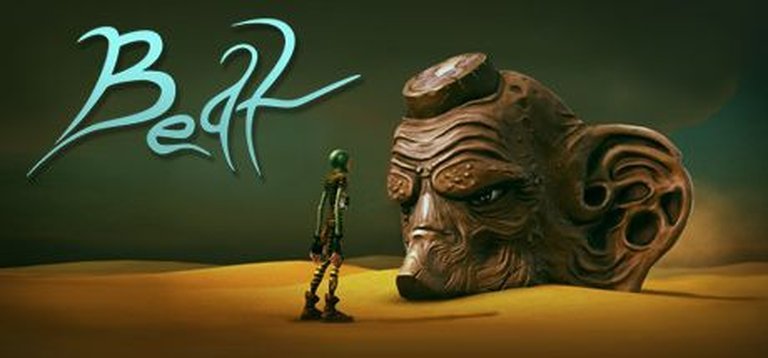

Beat the Game is a surreal, post-apocalyptic adventure set in a strange desert world. Players assume the role of a musically gifted traveler whose transport breaks down, forcing him to embark on a journey to repair it by performing a concert. The gameplay is a unique blend of graphic adventure, music/rhythm, and puzzle elements, where the player uses a special scanner to locate and mix environmental sounds to solve puzzles and progress through the bizarre, sci-fi landscape.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Beat the Game

PC

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (68/100): If you’ve got an ear for French house music and an eye for Salvador Dali, this game will be a sumptuous feast.

operationrainfall.com : Beat The Game feels more like a commercial of MTV from the 90s… it’s a unique experience that I feel everyone should try at some point.

saveorquit.com : Lovely artwork and sound but basic gameplay and very short.

adventuregamers.com : For me ‘unusual’ very quickly turned into ‘awesome’ once I got the hang of its unique gameplay.

Beat the Game: Review

In the vast and often predictable landscape of video games, there occasionally emerges a title so defiantly singular in its vision that it defies conventional critique. It exists not as a mere diversion, but as a statement—a piece of interactive art that challenges our very definitions of gameplay and narrative. Worm Animation’s 2017 debut, Beat the Game, is precisely such an artifact: a surreal, music-driven odyssey that is as breathtakingly beautiful as it is bewilderingly brief. It is a game that asks not to be beaten, but to be felt.

Introduction: A Symphony in the Sand

To discuss Beat the Game is to discuss the very essence of experiential media. Released into a gaming ecosystem dominated by sprawling open worlds and complex RPG systems, this title from the husband-and-wife team at Worm Animation LLC stands as a stark, beautiful contrast. It is less a game in the traditional sense and more a guided tour through a living, breathing music video—a Dali-esque dreamscape where the player is both the audience and the composer. Its thesis is simple yet profound: that the act of creation—of weaving a personal soundtrack from the disparate sounds of a broken world—can itself be the adventure. It is a bold, flawed, and unforgettable experiment that prioritizes aesthetic resonance over mechanical complexity, leaving players with an experience that is as polarizing as it is poignant.

Development History & Context: The Artist’s Game

Beat the Game was the inaugural project of Worm Animation LLC, a studio founded in 2013 by Cemre Ozkurt (Founder, Art Director) and Yesim Demirci Ozkurt (Co-Founder, Executive Producer). The credits reveal a small, tight-knit team of primarily artists and animators, with Cemre Ozkurt himself serving in a staggering number of roles, from story and programming to character and environment art. This is crucial to understanding the final product: Beat the Game was not born from a team of veteran game designers, but from a collective of visual artists and animators using the Unity engine to translate their unique vision into an interactive format.

The mid-2010s indie scene was a fertile ground for experimentation, with titles like Journey and Proteus demonstrating a market for short, atmospheric experiences. Worm Animation operated within this context but carved its own niche. There is no evidence of a large budget or publisher influence; this was a passion project, a digital art installation crafted by animators eager to step beyond commercial work and create something personal. The technological constraints of the era were largely sidestepped through a stylized art direction that favored bold, surrealistic shapes and a limited playable area, allowing their considerable artistic talent to shine without the need for photorealistic graphics or vast, processing-intensive worlds.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Sound of Silence

The narrative of Beat the Game is its most elusive and debated element. Players assume the role of Mistik, a character in striped pajamas who crashes his strange motorcycle in a vast, desolate desert. His initial quest for escape is almost immediately subsumed by a larger, more abstract goal: to collect sounds and perform a concert for an audience of geometric aliens.

The plot, as such, is virtually non-existent. It is a series of evocative, unexplained vignettes. A giant, weeping eyeball floats ominously in the sky. A mysterious red throne emerges from the sand, its wooden tendrils pulling Mistik underground. A cat-eared girl peeks from behind rusted machinery before fleeing. A giant clay man surfs across the dunes. These moments are presented without dialogue or exposition. The only guidance comes from a robotic voice from Mistik’s “Sound Scanner” and occasional text prompts, creating an atmosphere of isolated, dreamlike confusion.

This narrative minimalism is intentional. The game evokes the logic of a music video or a surrealist painting, where meaning is derived from emotion and symbolism rather than linear plot. Thematically, it explores ideas of creation from destruction. The landscape is explicitly post-apocalyptic; buried street lamps, half-sunk vending machines, and the husks of dead robots suggest a world that was once technological and is now reclaimed by sand and mystery. Mistik’s role is not to uncover what happened, but to respond to it artistically. He is an archetype of the artist in the wasteland, using the detritus of a fallen civilization—a soda can, a drumstick—to create new art and, in doing so, forge a new connection with the bizarre inhabitants of this new world.

The lack of concrete lore or character development is its greatest weakness for players seeking a traditional story, but its greatest strength as a piece of abstract art. It forces the player to project their own meaning onto the bizarre imagery, making the experience intensely personal. The “story” is the vibe, the mood, the act of sonic exploration itself.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Composer’s Toolkit

At its core, Beat the Game is a fusion of a simple graphic adventure and an intuitive music-creation tool. The gameplay loop is straightforward:

- Exploration: Guide Mistik through a small but densely detailed desert environment using direct third-person controls (keyboard/mouse or gamepad). The movement is deliberately slow and contemplative; there is no run button, forcing a pace that drinks in the scenery.

- Sound Hunting: Press ‘S’ to activate the Sound Scanner, a device that detects audio sources. These are often moving objects—a flying pig, a drifting geometric shape, a ghostly cat. To “collect” a sound, the player must keep the source within the scanner’s reticle for a few seconds.

- Music Mixing: Press ‘M’ to open a holographic mixer interface. Each collected sound is represented by a geometric icon. The player can toggle these sounds on/off, adjust their volume, and manipulate their playback speed. There is no “wrong” way to mix; the system is designed to be accessible to those with no musical training, allowing for instant, satisfying composition.

- Item Collection: Occasionally, Mistik will find physical objects (e.g., a drumstick, a soda can). These are used automatically in context, often unlocking new sounds (e.g., hitting the can with the stick creates a hi-hat sample) and triggering beautifully animated cutscenes that advance the vague narrative.

The genius of this system is its integration. The music you create isn’t just a minigame; it becomes the game’s diegetic soundtrack. As you wander the desert, your personal mix accompanies you, transforming the exploration into a dynamic audio-visual experience. Positive musical combinations are rewarded visually; the aforementioned clay man, Kumadam, will surf by with a message that he “likes your music.”

The primary criticism of the mechanics is their simplicity and the game’s extreme brevity. Most players will collect all 24 sounds and see the credits within 60 to 90 minutes. The final concert, a rhythm-based sequence where the player must activate and deactivate tracks in time with prompts, serves as the only real “challenge,” and it is over quickly. The world, while stunning, is small and bounded by invisible walls, preventing deeper exploration of its most intriguing landmarks.

For some, this makes it an overpriced tech demo. For others, it is a perfectly paced, curated experience—a interactive short story that doesn’t overstay its welcome. The gameplay is not about challenge or mastery; it is about discovery, experimentation, and the pure joy of creation.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Dream Painted in Sound

This is where Beat the Game transcends its mechanical limitations and becomes something truly special. The world-building is achieved almost entirely through its awe-inspiring art and sound design.

The visual direction is a masterclass in surrealism. The desert is rendered with a stark, realistic beauty, but it is populated with utterly fantastical elements: colossal, crumbling machinery; impossible floating structures; and creatures that feel pulled from the covers of psychedelic rock albums. The influence of artists like Salvador Dali and the music videos of Gorillaz or Daft Punk is palpable. The character designs for Mistik and the other entities he encounters are stylized and memorable, blending seamlessly with the more realistic environments to create a cohesive and deeply strange universe. This is the work of a confident animation studio flexing its muscles, and every frame could be a piece of concept art.

The sound design is the other half of the game’s soul. Initially, the world is silent save for the wind. This silence is the canvas upon which the player paints. The individual sounds—a glitchy pig snort, an ethereal synth pad, a crisp drum hit—are all high-quality and expertly curated. They are the game’s true collectibles. The act of mixing them is frictionless and empowering, making the player feel like a professional DJ with a suite of premium samples. The soundscape you create is personal and reactive, directly tying your actions to the audio experience in a way few games ever attempt.

Together, the art and sound create an overwhelming and consistent atmosphere of melancholic wonder. It is a world that feels both dead and alive, forgotten and waiting to be rediscovered through a new artistic language.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic’s Echo

Upon its release in September 2017, Beat the Game received a mixed-to-positive critical reception, perfectly reflecting its divisive nature.

- Adventure Gamers awarded it a 80% (4/5 stars), praising its “fresh sound-mixing experience” and “strange, wonderful world” while acknowledging its short length and lack of narrative.

- Metacritic settled at a 55 based on 6 reviews, with critics split between those who adored its artistry and those who dismissed it as an unsatisfying tech demo.

- User reviews on platforms like Steam were “Mostly Positive,” with players echoing the critical divide. The most common praises were for its “unique,” “beautiful,” and “trippy” experience, while the most common criticisms cited its extreme brevity and lack of gameplay depth.

Its legacy is not one of massive commercial success or widespread imitation, but of a respected cult classic. It stands as a prime example of a game as an “art game,” a title discussed more for its aesthetic achievements and bold conceptual framework than for its mechanics. It proved that a small team of artists could use accessible tools like Unity to deliver a visually stunning and conceptually unique experience.

While no wave of “sound-mixing adventures” followed, Beat the Game‘s influence can be felt in the continued acceptance of shorter, more experimental narrative titles. It shares DNA with games like Gorogoa or What Remains of Edith Finch, which also prioritize unique sensory experiences over traditional gameplay. It remains a benchmark for how to seamlessly integrate music creation into a game’s core loop, making the player feel like a genuine composer rather than just a consumer of a pre-recorded soundtrack.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Symphony

Beat the Game is an enigma. It is a game that is easier to admire than to recommend universally. To a player seeking a challenging, lengthy adventure with a rich story, it will be a profound disappointment. But to a player with an appetite for the experimental, the artistic, and the atmospheric, it is a hidden gem.

It is not a complete game in a traditional sense. It is a breathtaking, fleeting dream. It is a demo reel for a phenomenal animation studio that somehow became a playable experience. Its ending, which hints at a “to be continued” that never arrived, feels fitting. Beat the Game is not about resolution; it is about the journey and the music you make along the way.

In the annals of video game history, its place is secure not as a giant, but as a fascinating footnote—a beautiful, bizarre, and brilliantly executed experiment that dared to ask what a game could be when its primary goal was not to challenge your reflexes, but to unlock your creativity and leave you in awe of its visual and sonic poetry. It is a flawed masterpiece, a brief echo in the desert that, for those who listen closely, resonates long after the final note has faded.