- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: IM Group Sp. z o.o.

- Developer: Rebelmind

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

Description

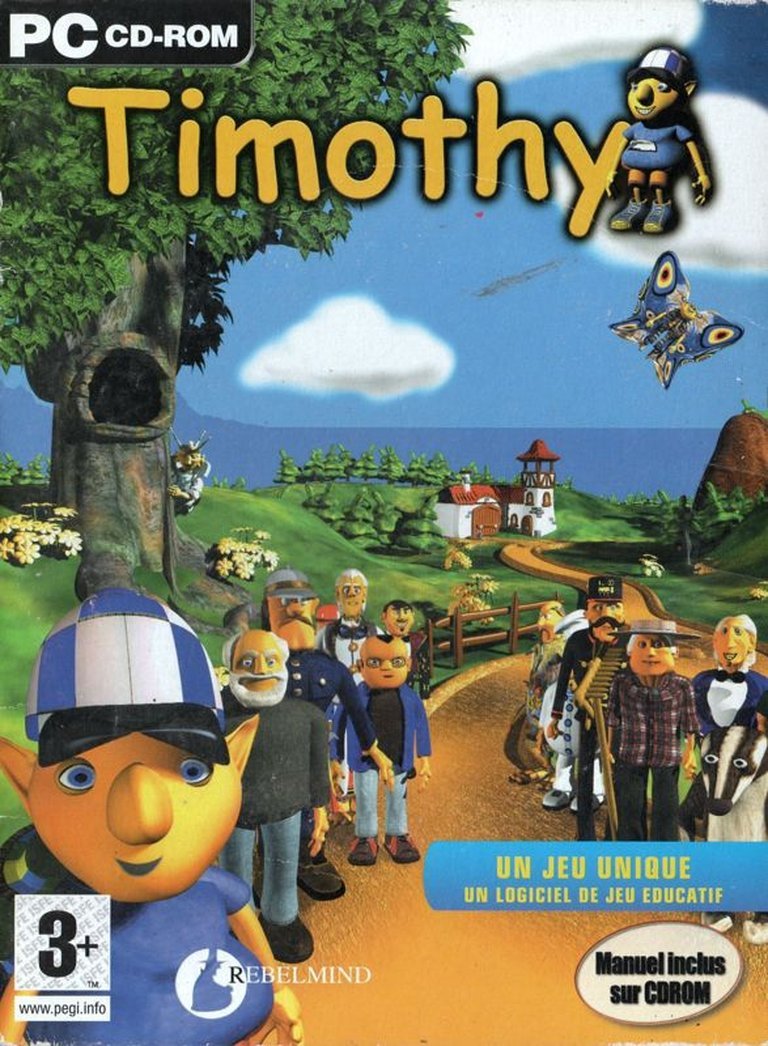

Timothy is an educational adventure game where players control a human-like creature named Timothy on a quest to rescue his captured friend, a butterfly named Basil. The evil Prince Skarboniusz has taken Basil, and Timothy must explore a vibrant island, collecting pieces of a magic map that leads to the prince’s kingdom. Gameplay involves 16 mini-games with three difficulty levels, focusing on puzzles and logic problems to develop children’s cognitive skills. The game is presented in a fully art-themed, non-textual environment where players learn mechanics through experimentation and interaction with the point-and-click world.

Timothy Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Timothy: A Forgotten Polish Edutainment Gem Lost to the Ages

In the vast, ever-expanding library of video game history, certain titles achieve legendary status, while others fade into obscurity, remembered only by a dedicated few. Then there are games like Rebelmind’s Timothy, which exist in a peculiar limbo—a title with a clear vision and a charming premise, seemingly lost to time itself. Released at the dawn of the new millennium, this Polish-developed edutainment adventure is a fascinating artifact of its era, a game that dared to teach through pure interaction and artful design, yet one that history has all but forgotten. This review seeks to excavate Timothy from the sands of time, analyzing its ambitious goals, its place in the gaming landscape of 2000, and the reasons for its enigmatic silence in the critical conversation.

Development History & Context

The Visionaries at Rebelmind

Timothy was developed by Rebelmind, a Polish studio that, according to the MobyGames credits, was a compact team led by the multi-hyphenate Darek Rusin, who served as Programmer, Project Manager, and Designer. This core team, including key designer and 3D artist Krzysztof Krawczyk, operated in a post-communist Polish game development scene that was still finding its footing on the global stage. The studio’s later works, such as the action-RPG Space Hack, suggest a team with ambitions beyond children’s software, making Timothy a intriguing early project that perhaps served as a technological and artistic proving ground.

The Technological and Market Landscape of 2000

The year 2000 was a pivotal moment for PC gaming. It was the era of 3D acceleration becoming standard, with titles like Deus Ex and The Sims redefining genre expectations. Yet, alongside these blockbusters, the edutainment market persisted as a lucrative, if often critically ignored, segment. This was the domain of Putt-Putt, Freddi Fish, and Pajama Sam from Humongous Entertainment—beloved point-and-click adventures that masterfully blended narrative with learning. Timothy was Rebelmind’s entry into this crowded fray. However, its technological approach was distinct. While its contemporaries often used 2D cartoon visuals, Timothy employed pre-rendered 3D backgrounds and characters, a technique popularized by Donkey Kong Country and early PlayStation RPGs. This gave the game a unique, plasticky, almost toy-like aesthetic that set it apart visually, even as it worked within the established “point-and-select” and “mini-games” framework of the genre.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Simple Tale of Friendship and Rescue

The narrative of Timothy is elegantly simple, designed to be immediately comprehensible to its young audience. The player controls the titular character, a benign, human-like creature living in idyllic harmony on a peaceful island with his best friend, a butterfly named Basil. This tranquility is shattered by the arrival of the archetypal villain, Prince Skarboniusz (in the Polish release), who captures Basil. Armed only with a magic map—conveniently torn into pieces—Timothy must traverse the island, interact with its quirky residents (the Gardener, the Musician, the Painter, the Fireman), and recover the fragments to chart a course to the prince’s kingdom and rescue his friend.

Thematic Execution: Learning Through Doing

The most profound thematic element of Timothy is its commitment to non-verbal learning. The game completely eschews text-based tutorials or explanations. A child player is not told how a puzzle works; they are expected to deduce it through experimentation, observation, and repetition. This “show, don’t tell” philosophy is a bold and theoretically sound educational approach, championing intuitive problem-solving and tactile discovery over rote instruction. The story itself reinforces themes of perseverance, friendship, and courage, but the true narrative is the child’s own journey of understanding the game’s logic and mechanics. The characters are not deep, psychological constructs but functional archetypes—the Musician owns a music-based puzzle, the Painter an art-based one—making them clear conduits for the gameplay rather than complex narrative entities.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Dual-Loop Structure

Timothy offers two primary modes of interaction, creating a dual gameplay loop:

1. The Adventure Shell: The player navigates the island in a fixed/flip-screen, point-and-click manner. This overworld is filled with interactive elements that trigger simple animations, a feature designed to encourage exploration and reward curiosity. This mode is the connective tissue, where the player learns the location of each resident and the map piece they guard.

2. The Mini-Game Core: The heart of the experience lies in the 16 mini-games, which can be accessed either through the story or directly from the main menu. These games cover a range of skills, from logic and pattern recognition to basic memory and reflexes, all under the umbrella of “developing mind skills.”

Analysis of Mechanics and Systems

The three difficulty levels for each mini-game suggest a thoughtful approach to scalability, allowing the game to grow with the child’s abilities. The use of both keyboard and mouse inputs for different games is also a smart way to familiarize young players with fundamental PC interfaces.

However, this is also where the game’s major flaw likely resides. Without any textual or vocal guidance, the leap from simply clicking on a character to understanding the often-abstract rules of their specific mini-game could be immense. The potential for frustration is high. A child’s natural curiosity could easily curdle into confusion if the logic of a puzzle proves too opaque. The success of this system is entirely dependent on the intuitiveness and flawless design of each individual game—a monumental task for any developer. The provided source material offers no critical insight into whether Rebelmind succeeded in this delicate balancing act, leaving it as the game’s great unanswered question.

World-Building, Art & Sound

A Pre-Rendered Island Paradise

The world of Timothy is crafted to feel like a living storybook. The use of pre-rendered 3D graphics gives the environments a cohesive and brightly colored aesthetic. Each screen, from the Gardener’s plot to the Painter’s studio, is a distinct, self-contained vignette. This “fixed-screen” approach creates a sense of stability and makes the world easily navigable for a child. The art direction, led by Marcin and Agnieszka Milewska-Krawczyk, aims for a friendly, non-threatening, and whimsical atmosphere where every object begs to be clicked on.

The Sound of Silence (and Music)

The audio landscape appears to be a key pillar of the experience. With a dedicated composer (Piotr Domiński) and sound designer (Janusz Borysiak), the game likely features a melodic, cheerful soundtrack that reinforces the sunny setting. The inclusion of voice acting, specifically by Roch Siemianowski in the Polish version and José Eduardo Silva in the translated release, is a significant production note. This suggests the characters might communicate through grunts, exclamations, or short phrases rather than dialogue, further emphasizing the game’s non-textual philosophy. The sound design would have been crucial in providing feedback—signaling success, failure, or interaction in lieu of written words.

Reception & Legacy

A Whisper, Not a Roar

The most telling fact from the source material is the complete absence of recorded reviews. MobyGames lists no critic reviews and no player reviews. It was collected by only four players on the site. This profound silence is its own form of critique. It suggests a game that, despite its ambitions, failed to make any significant commercial or critical impact upon release. It was likely overshadowed by the established giants of the edutainment genre and the flashier mainstream titles of the era. Its publisher, IM Group Sp. z o.o., does not appear to have been a major force in international distribution, possibly confining Timothy to a primarily Polish-speaking audience.

A Flickering Influence

The legacy of Timothy is not one of direct influence—it clearly did not reshape the genre. Instead, its legacy is archeological. It serves as a reminder of the hundreds of earnest, well-intentioned games developed in studios around the world that never found their audience. It represents a specific moment in Polish game development history and a particular approach to educational theory. For historians, it is a fascinating case study in ambitious design meeting market realities. Its existence highlights the sheer diversity of games produced in any given year, most of which never enter the mainstream historical record.

Conclusion

Timothy is a poignant paradox. It is a game built on a foundation of admirable principles: a belief in intuitive learning, a commitment to artful presentation, and a desire to create a pure, language-agnostic experience for children. Its technical execution, utilizing the pre-rendered 3D of its time, points to a studio with talent and ambition. Yet, for all its conceptual strength, it exists today as a mere ghost in the database—a game with credits, a premise, and screenshots, but no voice.

The ultimate verdict on Timothy cannot be one of quality, for that judgment has been lost to time. Instead, its place in video game history is that of a fascinating footnote. It is a beautifully crafted question mark. Was it a brilliantly designed educational tool let down by poor marketing? Or was its core mechanic of zero guidance a fundamental flaw that led to frustration? We may never know. Timothy remains an enigmatic artifact: a testament to the countless creative visions that flicker into existence only to retreat into the silent, vast archives of gaming history, waiting for a historian to point, click, and wonder what might have been.