- Release Year: 1976

- Platforms: Antstream, Arcade, Atari 2600, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Atari Corporation, Atari Interactive, Inc., Microsoft Corporation, Namco Limited, Sears, Roebuck and Co., Taito Corporation, Universal Sales Co., Ltd., Video Games GmbH

- Developer: Atari Corporation

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Paddle, Pong

Description

Breakout is a classic arcade action game released by Atari in 1976. The player controls a paddle at the bottom of the screen, using it to bounce a ball upwards towards a wall of colored bricks at the top. The objective is to destroy all the bricks by hitting them with the ball while ensuring the ball does not fall off the bottom of the screen. The game features several variations, including a mode where the ball breaks through bricks without bouncing back, a timed challenge, and a version where bricks are invisible until hit.

Where to Buy Breakout

PC

Breakout Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Breakout: A Foundational Pillar of the Arcade Era

In the pantheon of video game history, few titles can claim to be both a foundational pillar and a direct progenitor to an entire genre. Breakout is one such game—a deceptively simple concept that distilled the competitive essence of Pong into a solitary, meditative, and utterly compelling test of skill and rhythm. This is not merely a review of a game; it is an archaeological dig into the very bedrock of interactive entertainment, a study of a moment when a bouncing ball and a wall of bricks captured the imagination of a generation and set in motion a chain of innovation that would ripple through the industry for decades.

Development History & Context

The Atari Vision and the Wozniak-Jobs Hacker Ethos

Breakout was released by Atari, Inc. into arcades in May 1976, a mere three years after the company had ignited the commercial video game industry with Pong. The vision, as credited to Atari founder Nolan Bushnell and engineer Steve Bristow, was to create a single-player version of Pong—a game where the player wasn’t competing against another person or a crude AI, but against a static structure, a system of physics to be mastered.

The development lore of Breakout is the stuff of industry legend, primarily due to the involvement of two individuals who would later define personal computing: Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs. Tasked with creating a prototype with a drastically reduced chip count to save on manufacturing costs, Wozniak, with Jobs’ assistance, engineered a masterpiece of hardware efficiency. This collaboration was a perfect fusion of Atari’s commercial ambition and the Silicon Valley hacker ethos—a drive to do more with less, to bend technology to its absolute limits. The technological constraints of the era were severe; every transistor was precious, and the goal was to create a compelling experience with the most minimalist of components. This was not an era of narrative depth or graphical splendor; it was an era of pure, abstract mechanics born from necessity.

The gaming landscape of 1976 was still in its infancy. The arcade was dominated by Pong clones and early shooters like Gun Fight. Breakout arrived as a novel concept: a solo experience that was both accessible and deeply challenging, offering a tangible goal—the complete destruction of a wall—that was visually satisfying and easy to understand.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Zen of Destruction

To approach Breakout looking for a traditional narrative—with characters, plot, and dialogue—is to miss its point entirely. Its narrative is one of action and reaction; its characters are the player, the paddle, and the ball. Its plot is the slow, methodical deconstruction of a barrier, brick by brick.

Thematically, Breakout is a game about order versus chaos, construction versus deconstruction. The wall of multi-colored bricks (a rainbow formation that, as reviewer Woodgrain Wonderland noted, “must have blew some peoples’ minds back in ’78”) represents a structured, orderly system. The player, armed only with a bouncing sphere, is the agent of chaos. The underlying theme is one of obsessive perseverance, a journey documented in David Sudnow’s 1979 book, Pilgrim in the Microworld, which chronicled his deep, almost philosophical dive into the game’s mechanics. The dialogue is the silent conversation between the player’s movements and the ball’s physics; the drama is in the near-miss, the perfect ricochet, and the inevitable failure. It is a game about the journey, not the destination, where the only story told is the one written by the player’s own performance on the high-score board.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Elegance of a Single Loop

The core gameplay loop of Breakout is a paradigm of elegant simplicity:

1. Launch the ball.

2. Use the paddle to bounce it upward into the wall of bricks.

3. A brick hit is a brick destroyed.

4. Prevent the ball from falling off the bottom of the screen.

5. Repeat until the wall is gone or all balls are lost.

This loop belies a surprising depth. The ball’s physics are everything. The angle of deflection is determined by where the ball makes contact with the paddle—hit it dead center, and it will rebound straight up; hit it on the edge, and it will shoot off at a sharper angle. This simple rule is the heart of the game’s skill ceiling. Master players, as noted by contributor RobinHud, learn to “dig a hole” through the sides early to allow the ball to ricochet wildly between the top of the screen and the upper layers of bricks, a strategy that racks up points quickly but requires immense precision as the paddle shrinks with each level cleared.

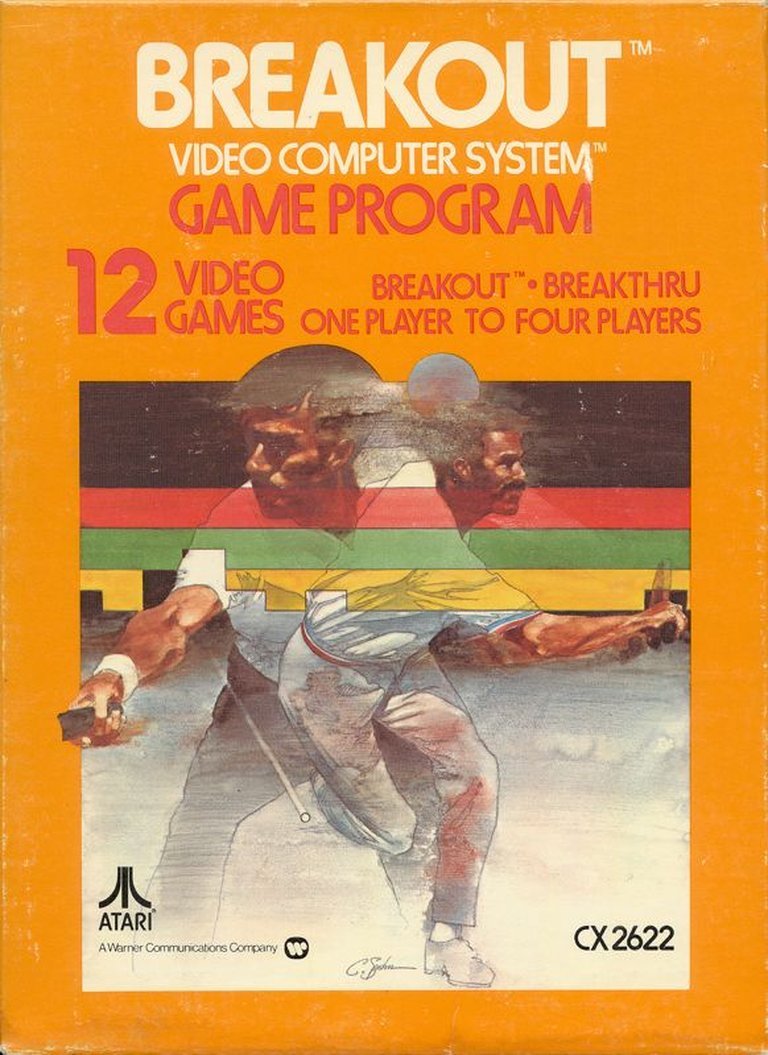

The game’s longevity is bolstered by its variations, a concept that was revolutionary for a cartridge-based console port. The Atari 2600 version, released in 1978, famously offered 48 different modes. These included:

* Breakthru: Where the ball plows through bricks without bouncing, changing the strategic focus from angles to sheer speed.

* Catch: The ability to “catch” the ball with the paddle to reposition it, adding a layer of tactical planning.

* Invisible: The bricks vanish after being hit, forcing players to rely on memory.

* Timed: A race against the clock for a high score.

While some critics, like The Good Old Days, found these variants “half-hearted,” they represented an early attempt to extend replayability and cater to different skill levels. The UI is the game itself—a scoresheet and lives counter—requiring no tutorial or explanation. The innovation was in its purity; the flaw, as noted by many reviewers, is the potential for repetition. Without the power-ups and level diversity of its successors like Arkanoid, Breakout can feel like a pure, unadorned test of skill—which is either its greatest strength or its most significant weakness, depending on the player’s perspective.

World-Building, Art & Sound

A Symphony of Minimalism

The world of Breakout is an abstract digital plane. There is no setting beyond the black void of the screen. The atmosphere is generated entirely by the tension of the gameplay—the frantic tracking of the ball, the satisfaction of a brick exploding into nothingness, the dread of a missed catch.

The visual direction is defined by functional clarity. The colored bricks provide a clear target and a sense of progression. The transition from the vibrant rainbow walls of the early stages to the sparse remaining bricks of the later stages creates a powerful visual metaphor for the player’s advancement. On the Atari 2600, the graphics were rudimentary but effective, a feat considering the hardware’s severe limitations.

The sound design is a hallmark of the era: simple, generative beeps and bloops that function as audio cues. The “thunk” of the paddle connecting, the higher-pitched “ping” of a brick being hit, and the ominous silence of the ball falling—these sounds are as integral to the experience as the visuals. They are the game’s soundtrack and its feedback system, a minimalist symphony that perfectly complements the on-screen action. As one reviewer quipped, you could always turn the sound off, but in doing so, you’d lose a key part of its raw, arcade soul.

Reception & Legacy

From Arcade Novelty to Genre Foundation

Upon its release, Breakout was a significant commercial success. It carved out a space in the arcade next to its multiplayer brethren, offering a different kind of engagement: a personal, almost zen-like challenge. Its critical reception was built on its concept and addictiveness, with publications like Creative Computing in 1978 praising its “48 versions.”

Its true legacy, however, is immeasurable. As The Retro Archives review (translated) succinctly put it, Breakout “will forever remain the founder of the brick-breaker genre.” It provided the DNA for thousands of clones, homages, and evolutions, most notably Taito’s Arkanoid in 1986, which added power-ups, enemy ships, and complex level design, building directly upon *Breakout‘s foundation.

The game’s influence extends far beyond the genre it created. Its design philosophy of simple-to-learn, difficult-to-master mechanics became a cornerstone of game design. Furthermore, its development was a key chapter in the story of Apple Inc., with the work done by Jobs and Wozniak funding the early development of the Apple I computer. It appears in the book 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die, cementing its historical importance.

The evolution of its reputation is typical of foundational texts; modern critics often find it “tedious” (The Game Hoard) or “archaic” (The Video Game Critic) when judged against its more complex descendants. Yet its status as a classic remains untarnished. It has been re-released and included in countless compilations like Atari Vault and Atari 50: The Anniversary Celebration, ensuring new generations can experience this seminal piece of history.

Conclusion

The Verdict: An Imperishable Monument

Breakout is not a game that can be judged solely by contemporary standards of content or complexity. To do so would be like criticizing the Wright Flyer for not having jet engines. Its significance is historical, mechanical, and cultural. It is a masterpiece of minimalist design, a game that proves a profound experience can be built from the most basic elements: a goal, an obstacle, and a tool.

It is a game of two minds. On one hand, it is a repetitive, limited experience that can be exhausted quickly. On the other, it is an endlessly compelling score-attack puzzle, a test of reflexes and geometry that remains satisfying in short, intense bursts. Its MobyScore of 6.5 reflects this dichotomy—a respectable score for a game that many respect more than they love.

Ultimately, Breakout‘s place in video game history is unassailable. It is a direct evolutionary link between Pong and the modern era, a catalyst for innovation, and a timeless example of how a perfect idea can emerge from severe technical constraints. It is the forefather of a genre and a monument to the ingenuity of its creators. While you may not play it for hours on end, to understand video games, you must understand Breakout. It is, quite simply, essential.