- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Agence nationale pour la gestion des déchets radioactifs

- Developer: Touche Etoile

- Genre: Ecology, Educational, Nature, Science

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Decommissioning, Quizzes, Storage Management, Waste Collection

Description

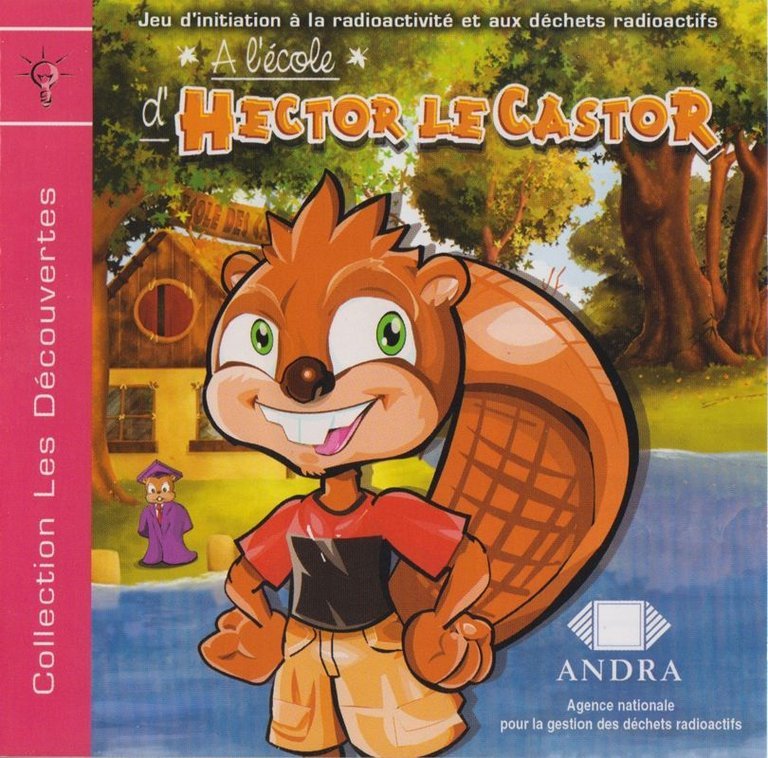

A l’école d’Hector le Castor is an educational PC game developed by the French Agence Nationale pour la gestion des Déchets Radioactifs (ANDRA) to teach players about radioactive waste management. Players follow Hector the Beaver through school lessons on radioactivity fundamentals, then engage in mini-games focused on classifying high/low-level waste and safely handling storage/disposal procedures. The 2004 release blends environmental science education with light gameplay elements.

A l’école d’Hector le Castor: Review

Introduction

In an era dominated by blockbuster franchises and high-octane action titles, A l’école d’Hector le Castor emerges as a curious artifact of gaming history—a didactic experiment funded by France’s nuclear waste authority. Released in 2004 as a free CD-ROM, this educational hybrid aimed to demystify radioactivity through the whimsical lens of Hector, an anthropomorphic beaver. While lacking critical acclaim or commercial fanfare, the game represents a fascinating intersection of civic education and early 2000s game design. This review argues that Hector le Castor, despite its mechanical simplicity, stands as a unique case study in how games can reframe complex scientific topics for public engagement, even if its execution remains uneven.

Development History & Context

Developed by the obscure French studio Touche Etoile and published by the Agence nationale pour la gestion des déchets radioactifs (ANDRA), A l’école d’Hector le Castor was born from a governmental initiative to educate citizens about nuclear waste management. The early 2000s marked a pivotal moment for environmental awareness in Europe, with France heavily reliant on nuclear energy. ANDRA sought to leverage gaming—a medium gaining traction in educational spheres—to make radioactive waste relatable to younger audiences.

Technologically, the game was constrained by the CD-ROM format and the era’s modest computing power, resulting in 2D graphics and rudimentary interactivity. The development landscape at the time favored mass-market titles, leaving niche educational projects like this underfunded and reliant on minimalist design. Unlike contemporaries such as Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?, Hector le Castor lacked broad institutional backing, limiting its scope. Its release in March 2004 for Windows and Macintosh flew under the radar, overshadowed by mainstream hits like World of Warcraft and Half-Life 2.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The game’s narrative is didactic rather than dramatic. Players follow Hector le Castor, a cheerful beaver mascot, through a series of lessons about radioactivity’s applications and risks. The framing device casts learners as students in Hector’s “school,” where quizzes on nuclear science precede practical waste-management tasks. Dialogue is minimal, with Hector delivering exposition via text bubbles in a paternalistic yet approachable tone.

Thematically, the game emphasizes civic responsibility and scientific literacy. It refrains from alarmism, instead framing waste management as a solvable challenge. Subtextually, it mirrors France’s pro-nuclear stance by normalizing radioactivity as a manageable byproduct of progress. However, its anthropomorphic protagonist and simplified dialogue risk trivializing the subject—a double-edged sword that may engage children but underserve older audiences.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

A l’école d’Hector le Castor centers on three core mechanics:

1. Educational Quizzes: Players answer multiple-choice questions on radioactivity basics (e.g., definitions of isotopes, uses in medicine). Correct responses unlock mini-games.

2. Waste Sorting: A drag-and-drop mini-game tasks players with categorizing objects as high- or low-level radioactive waste, emphasizing real-world classifications.

3. Waste Handling: A step-by-step simulation where players follow protocols for storage/decommissioning, requiring logical sequencing.

The UI is functional but dated, with static menus and mouse-driven controls. Progression is linear and binary—failure locks players until mastery—reinforcing its educational aims but limiting replayability. The mini-games suffer from repetitive feedback loops, with limited visual variety. While innovative in its time for tackling real-world science, the lack of adaptive difficulty or narrative branching undermines engagement.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s aesthetics evoke early-2000s edutainment: Hector’s school is rendered in flat, primary-colored backgrounds with simplistic iconography (e.g., beaver dams as metaphors for containment). Hector’s design—a buck-toothed, wide-eyed beaver in a lab coat—balances charm and clarity, though animations are limited to looping idle motions. Environmental details (classroom posters, waste facility schematics) subtly reinforce educational content.

Sound design is sparse, featuring generic MIDI-style background music and minimal voice-acting (Hector occasionally chatters in muffled squeaks). The absence of diegetic sound in mini-games feels like a missed opportunity to enhance immersion. While the visuals serve their purpose, they lack the polish of contemporaries like Pajama Sam.

Reception & Legacy

A l’école d’Hector le Castor garnered no formal reviews upon release, reflecting its niche status. Its distribution as freeware via ANDRA’s website limited commercial impact, though it may have surfaced in French classrooms. The game’s legacy lies in its audacious premise—few titles dare to gamify nuclear waste—but its influence on later eco-conscious games (Fate of the World, Eco) is tenuous.

Technically, it foreshadowed the rise of “serious games” for civic education, albeit without the interactivity of later successes like Foldit. Today, it exists as a cult oddity, occasionally cited in academic papers on gamified public policy. For ANDRA, it remains a curious footnote in their outreach efforts, overshadowed by modern digital campaigns.

Conclusion

A l’école d’Hector le Castor is neither a masterpiece nor a failure. It is a earnest attempt to merge gaming with public education, constrained by budgetary realities and technological limits. While its gameplay loops feel archaic and its pedagogical approach heavy-handed, the game’s very existence challenges the industry to consider games as tools for societal dialogue. In an age of climate crises, Hector’s lessons on responsibility resonate more than ever—even if his execution is better suited to a museum exhibit than a living room. For historians of educational gaming, it offers invaluable insights; for modern players, it’s a charming relic of 2004’s optimism about games’ power to inform. Its place in history is secure, if modest: a beaver who tried to change the world, one radioactive waste quiz at a time.