- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: Data Design Interactive Ltd, Fairprice Games, Metro3D Europe Ltd., Popcorn Arcade

- Developer: Data Design Interactive Ltd

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Automobile, Track racing, Vehicle simulator, Vehicular

- Setting: Action girlz high, Aquacoral resort, Dolphin bay resort, Fairytale castle, Sunset lagoon

- Average Score: 21/100

Description

Action Girlz Racing is an arcade-style kart racing game featuring eight female characters competing in miniature cars across whimsical tracks like fairytale castles and tropical resorts. Players unlock characters, tracks, and racing classes (50cc, 100cc, 150cc) by collecting flowers earned during races, utilizing power-ups such as nitro and shields to gain advantages. The game supports multiplayer on Wii with motion controls for up to four players and on PS2 for up to four players using a Multi-Tap.

Gameplay Videos

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (19/100): It’s a horrid product full of terrible track design, lifeless characters and glitched programming that’s only service to its developer and publisher is to make all their other bargain bin games look better by comparison.

ign.com : Grab your lipstick, start your engine and get ready for, quite possibly, the worst Wii game of 2008.

Action Girlz Racing: A Cautionary Tale of Shovelware and Misogyny

Introduction

In the annals of video game history, certain titles transcend mere mediocrity to achieve notoriety for their breathtaking incompetence. Action Girlz Racing, developed by Data Design Interactive (DDI) and published across multiple platforms from 2005 to 2008, stands as a monument to rushed development, predatory monetization, and cynical gender marketing. Promoted as “the only racing game designed by Girls, for Girls!”, the game instead delivered a shallow, glitch-ridden experience built on recycled assets from the developer’s earlier Myth Makers: Super Kart GP. This review dissects the legacy of Action Girlz Racing, examining its origins, mechanics, thematic failures, and its indelible mark as one of the most reviled kart racers ever created. Our thesis is clear: despite its superficially colorful facade, Action Girlz Racing represents a nadir in licensed and shovelware gaming—a cautionary tale of how not to target a specific demographic while failing on every conceivable level.

Development History & Context

The DDI Assembly Line and the GODS Engine

Action Girlz Racing emerged from Data Design Interactive, a UK studio infamous for its “quantity over quality” approach to budget titles. The game was not an original creation but a reskin of Myth Makers: Super Kart GP (released just one month prior), sharing its core engine, assets, and fundamental structure. This practice, dubbed the “GODS Technology” (Game Oriented Development System), allowed DDI to rapidly produce similar-looking games—Action Girlz Racing, Myth Makers: Trixie in Toyland, Monster Trux Extreme—by merely swapping textures and superficial labels. The engine utilized the RenderWare middleware for graphics and the Havok physics engine, yet both were implemented poorly, contributing to the game’s technical woes.

Marketing Deception and Targeted Demographics

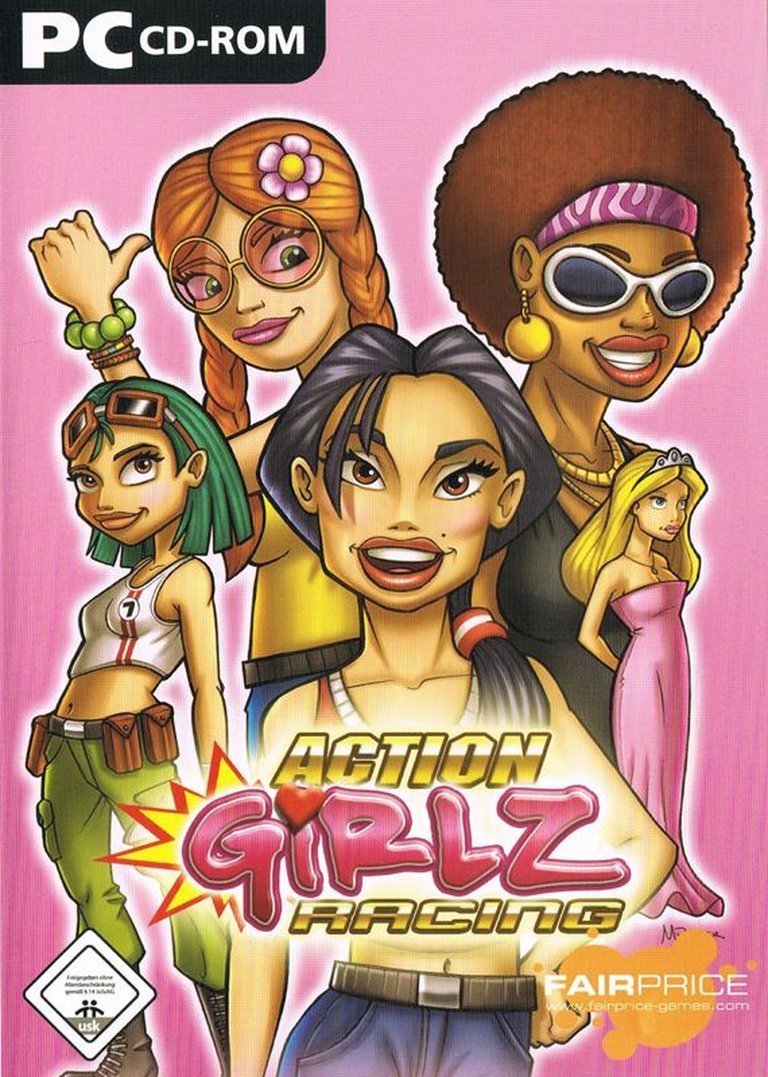

Published in Europe by Metro3D and later by Conspiracy Entertainment in North America, the game’s marketing leaned heavily on gendered messaging. The cover and advertisements emphasized “girl power,” vibrant aesthetics, and a cast of eight customizable female drivers. However, this facade crumbled upon examining the credits. Names like “Karla White,” “Julia Alden-Salter,” and “Teowoman Hermak” were revealed to be female pseudonyms for male programmers (Karl White, Julian Alden-Salter, Teoman Irmak), a practice exposed by sources like VGFacts. The audio production was handled by Paul Weir, a man credited on No Man’s Sky. This discrepancy between “made by girls” marketing and the reality of a male-dominated development team constitutes a significant case of false advertising, highlighted by Qualitipedia and IGN.

Technological Constraints and the Wii Port

While leveraging middleware like RenderWare and Havok, the games suffered from severe underutilization. The initial 2005 Windows and PlayStation 2 releases were technically mediocre, plagued by low-resolution textures and basic visuals. The 2007 Wii port, released two years after the original, exemplifies DDI’s lack of polish. The motion controls were simplistic (tilt-based steering), and the game suffered from unstable framerates, frequent crashes, and graphical glitches. A planned PlayStation Portable version was canceled, likely due to DDI’s shifting priorities and the game’s already poor reception. The development cycle was rushed, evident in the abundance of unused assets (Xbox controller models, Nickelodeon Party Blast text files, BT music tracks) discovered by The Cutting Room Floor, suggesting minimal debugging or optimization.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Story of Unlocking… and Stereotypes

Action Girlz Racing features no traditional narrative. Instead, it presents a shallow premise: race as one of eight “Action Girlz” across whimsical tracks. Character profiles provided in marketing materials and the game’s description paint a picture of one-dimensional archetypes:

– Kat: “Action girl with no fear,” described as loving curves and post-race drinks.

– Latisha: “So cool you have to check for a pulse,” portrayed as aggressive and stereotypically “cool” with a focus on overtaking.

– Bianca: “Professional” who “uses her head” but “knows how to have fun,” a classic “brains but also social” trope.

– Amber: “More concerned with looks,” valuing winning “in style,” reducing her to a superficial beauty archetype.

– Akiko: Tied to indie music and tap-dancing, an attempt at diversity that feels tokenistic.

– Blossom: Harnesses “flower-power,” described as “passionate yet relaxed,” leaning into hippie stereotypes.

– Courtney: Claims her own “cool” style, mimicking Latisha’s overtaking obsession.

These descriptions lack depth, personality, or agency. Characters are defined by single traits or hobbies, with no backstory or development. Critically, Qualitipedia notes that Latisha is “very crass and stereotypical,” and Kat is “a poor trace of Sami from Advance Wars,” suggesting lazy design rather than meaningful character creation.

Thematic Failures: Misogyny in Marketing and Gameplay

The game’s central theme—empowerment through racing—is undermined by its execution. While marketed to girls, the gameplay reinforces negative stereotypes:

1. Appearance Over Substance: Characters differ only in appearance, not abilities, undermining claims of unique personalities or skills. Unlocking them is a tedious grind tied to collecting flowers.

2. Monetization of “Girly” Elements: The flower currency system turns a core mechanic into a predatory grind. Players must repeatedly race to unlock basic content (characters, tracks), a practice highlighted as a DDI staple.

3. Passive Objectification: Character designs resemble “rejected Barbie or Bratz dolls” (Qualitipedia), emphasizing aesthetics over agency. Their biographies focus on drinks, curves, and looks, not racing prowess or personal goals.

4. Contradiction in Credits: The “designed by girls” claim is exposed as false by the credits, reinforcing a sense of exploitation rather than genuine representation. This disconnect between marketing and reality is a profound thematic failure, reducing female representation to a cosmetic label.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Racing: A Flawed Foundation

The kart racing mechanics are fundamentally broken, mirroring the flaws of its predecessor, Myth Makers: Super Kart GP:

– Camera and Controls: The “behind view” camera is notoriously tight, making it difficult to see upcoming turns or hazards. Controls are “unresponsive and overly sensitive” (Qualitipedia), leading to frustrating drifts and collisions. The Wii tilt controls, while simple, lack precision.

– Track Design: Tracks suffer from severe issues:

– Cramped Layouts: Curves appear without warning, causing constant, unavoidable wall collisions.

– Intentional Dead Ends: Branching paths often lead to dead ends, forcing players to backtrack and lose significant positions (IGN, TCRF). This is not strategic choice but poor design.

– Lack of Variation: Despite marketing “5 bright, engaging race levels” and “10 Track variations (5 daytime, 5 night time)” (GamePressure), the actual track count is limited and designs are uninspired (“fairytale castle,” “sunset lagoon,” “action girlz high”).

– Physics and Collision: The Havok engine is misused. Cars frequently flip over after hitting walls at low speeds (Qualitipedia). Collision detection is unreliable, allowing players to “fly through” walls into voids, often resetting them to 8th place (IGN). Colliding with a “chatter shot” (stun power-up) immobilizes the player completely.

Combat and Power-Ups: Shallow and Frustrating

The game attempts a Mario Kart-style combat system but fails spectacularly:

– Limited Arsenal: Only eight power-up types exist (nitro, umbrella shield, shooting, stunning, etc.). They are functionally identical to those in Myth Makers, lacking creativity or impact.

– Power-Up Doubling: Collecting diamonds “maxes out” power-ups, adding a layer of pointless complexity. The system feels tacked on and underdeveloped.

– Effectiveness: Power-ups have minimal impact. Shooting and stunning are unreliable, shields are easily broken, and nitro boosts are negligible compared to the core physics frustrations.

Character Progression and Unlocking: Predatory Monetization

The progression system embodies DDI’s exploitative approach:

– Locked Content: Initially, only one character and one track are available. The remaining seven characters, multiple tracks, and higher engine classes (50cc, 100cc, 150cc) must be unlocked by collecting “flowers” during races. This grind is mandatory to experience the bulk of the game.

– Meaningless Customization: Characters have zero stat differences (speed, handling, acceleration). Unlocking them offers zero gameplay advantage, making the process purely cosmetic and tedious.

– Difficulty Imbalance: Beginner mode karts move “very slowly,” making races “dull” and laps take “two minutes” (Qualitipedia). Higher difficulties offer little challenge beyond increased AI rubber-banding.

UI and Modes: Clunky and Limited

The user interface is utilitarian and uninspired:

– Menu Design: Simple but functional, mirroring DDI’s template. The save screen is identical across their titles (Nintendo Fandom).

– Game Modes: Three modes are offered (Single Trial, Time Trial, Grand Prix). Grand Prix involves racing cups across unlocked tracks. Time Trial is a standard test mode. Single Trial allows quick races on available tracks. There is no story mode, only these basic structures.

– Multiplayer: The Wii version supports local 4-player split-screen. The PS2 version allows 2 players natively or 4 with a Multi-Tap. However, the technical issues (physics, camera) make multiplayer equally frustrating.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Art Direction: Colorful but Crude

The game’s visual aesthetic tries to mimic the vibrant, cartoonish style of successful kart racers like Mario Kart, but falls short dramatically:

– Character Design: The eight “Action Girlz” are rendered with blocky, low-polygon models resembling “rejected Barbie or Bratz dolls” (Qualitipedia). Their designs are generic, relying on hair color and simple accessories (tiaras, umbrellas) for distinction. Animations are stiff and lacking in personality.

– Environment Design: Tracks like “Fairytale Castle,” “Sunset Lagoon,” and “Action Girlz High” are visually monotonous. Textures are blurry and repetitive. Environments lack detail or atmosphere. The “fogging” effect (objects merging into the sky in the distance) is poorly implemented, clipping awkwardly.

– Technical Failures: The RenderWare engine is pushed beyond its capabilities. Textures pop in, models clip through each other, and lighting is flat and unappealing. The visual presentation is consistently described as “blocky,” “terrible,” and “awful” across sources.

Sound Design: Annoying and Repetitive

The audio experience is universally panned:

– Music: Tracks are generic, uninspired loops. IGN notes the music is “copied from other Data Design video games,” lacking originality. Themes become grating quickly due to repetition.

– Sound Effects: Engine sounds are generic and weak. Collision sounds are inconsistent. Power-up effects are underwhelming.

– Voice Acting: Characters have minimal voice lines. IGN highlights that “one character in the game repeats the same voice line over and over,” becoming incredibly irritating. The overall soundscape is flat and contributes to the game’s lifeless feel.

Atmosphere: A World Without Charm

Despite its “whimsical” setting, Action Girlz Racing fails to create an engaging atmosphere. The tracks lack personality beyond their basic theme names. There are no environmental details, interactive elements, or dynamic events to make the world feel alive. The combination of poor visuals, repetitive audio, and frustrating gameplay results in an experience that is not just unpleasant, but actively draining. The intended “fun, girl-centric” vibe is completely overshadowed by technical incompetence and design flaws.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Scorn: Universal Disappointment

Action Girlz Racing received near-universal negative reviews, cementing its place among gaming’s worst:

– Metacritic: Aggregated critic score of 23% (based on 3 reviews). PC Action (Germany) scored 42%, calling it “verdammt bescheiden” (damn poor) and “on no motivating.” 7Wolf Magazine (Germany) gave it 20%, a “nicht bemerkbar” (unremarkable) children’s simulator. IGN’s Wii review (2009) is the most infamous, awarding a 0.8/10 and declaring it “quite possibly, the worst Wii game of 2008.” Reviewer Lucas M. Thomas called it a “horrid product full of terrible track design, lifeless characters and glitched programming.”

– Player Reception: Metacritic users scored it 1.9/10 (Overwhelming Dislike). Common player complaints mirror critics: “trash,” “awful,” “glitching,” “unresponsive controls,” “terrible graphics.” MyAbandonware users rate it 3.1/5, acknowledging its budget status but calling it “above-average vehicle simulator in its time” – a generous take given the context.

– Legacy Rankings: It holds notoriously low ranks on GameFAQs (second-lowest PS2 game, ninth-lowest Wii game), becoming a benchmark for bad games.

Commercial Performance and Cultural Impact

While exact sales figures are scarce, the game’s status as budget shovelware ($6.88 used on PS2) and its critical drubbing suggest minimal commercial impact beyond the bargain bin. Its cultural impact lies in its infamy. It has become a shorthand for terrible licensed games and predatory development practices. It’s frequently cited in discussions of “worst games ever,” alongside other DDI titles like Ninjabread Man and Anubis II. The “designed by girls, for girls” marketing debacle remains a textbook example of deceptive advertising targeting a specific demographic.

Influence on the Industry

Action Girlz Racing served as a cautionary tale for publishers and developers:

1. Asset Flipping Exposed: It highlighted the dangers of recycling engines and assets without meaningful iteration, damaging DDI’s reputation irreparably.

2. Target Demographics Done Wrong: It demonstrated how cynical gender marketing combined with poor execution alienates the very audience it claims to represent, leading to backlash.

3. Shovelware Benchmark: It solidified the Wii’s reputation for low-quality shovelware, contributing to the perception that the platform lacked quality control. Its preservation on sites like The Cutting Room Floor underscores its value as a historical artifact of poor game design.

Conversely, its negative reception contrasts sharply with successful kart racers like Mario Kart Wii (released the same year), emphasizing the importance of polish, innovation, and respect for the player.

Conclusion

Action Girlz Racing stands as a definitive artifact of video game shovelware, a title where every conceivable facet of development and design failed. Its genesis in asset-flipping, its deceptive “girl power” marketing, its fundamentally broken gameplay physics, its predatory unlock system, and its soulless presentation coalesced into an experience universally reviled by critics and players alike. While its technical limitations can be contextualized within the constraints of budget development in the mid-2000s, its thematic failures—particularly the exploitation of its target demographic through false advertising and the creation of shallow, stereotyped characters—are inexcusable. The game’s legacy is one of infamy, serving as a constant reference point for discussions about terrible game design and cynical monetization practices. It achieved historical significance not through innovation or quality, but as a monument to what happens when development prioritizes speed and profit over player experience and integrity. In the pantheon of video game history, Action Girlz Racing is less a game and more a cautionary tale—a stark reminder that even the most vibrant marketing cannot disguise a core rot of technical incompetence and thematic bankruptcy. Its place is secured not as a classic, but as a benchmark for failure.