- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Ubisoft Entertainment SA

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

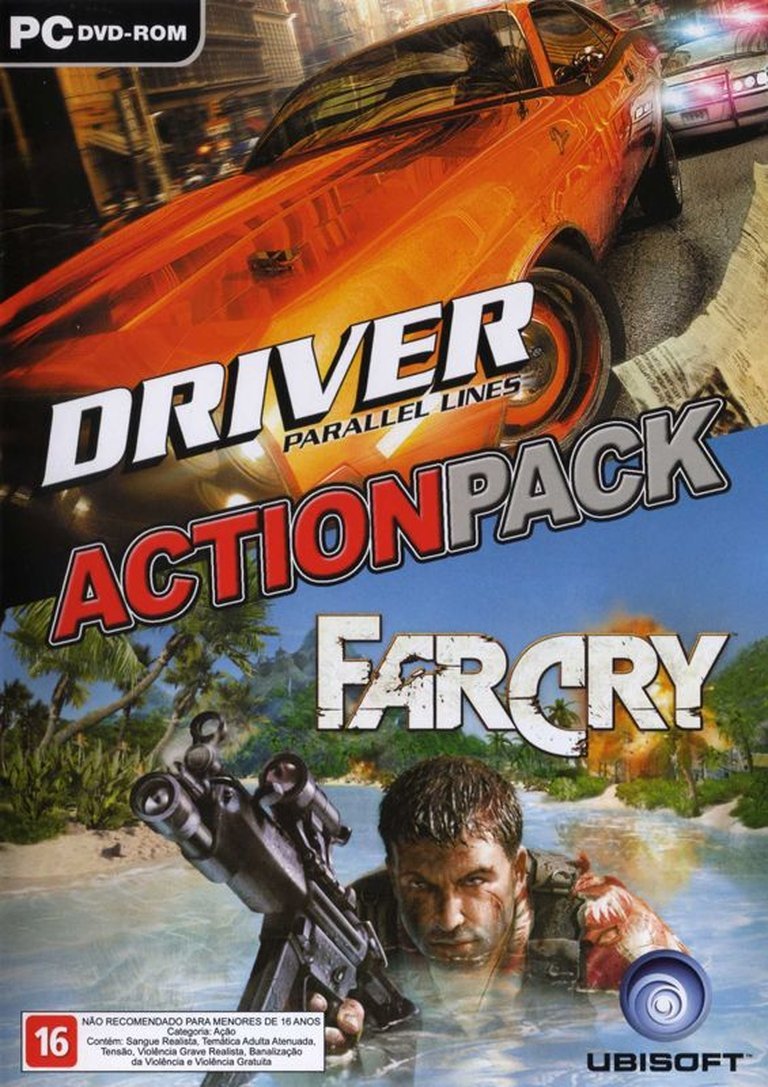

Action Pack – Driver: Parallel Lines + Far Cry is a 2010 Windows compilation that includes two separate games: Driver: Parallel Lines (2006), which is noted for introducing a scarier vision with explicit blood and death to the Driver series, and Far Cry (2004). Based solely on the provided text, no specific details about the settings or full narrative premises of these individual games are elaborated, with the compilation simply listed as containing both titles.

Action Pack – Driver: Parallel Lines + Far Cry: A study in divergent eras and bundled legacy

Introduction: Two Games, One Case—A Snapshot of a Transitional Era

In the annals of video game history, compilation packs often serve as curious time capsules, bundling disparate titles from different creative eras into a single commercial package. Ubisoft’s 2010 Windows release, Action Pack – Driver: Parallel Lines + Far Cry, is a quintessential example. It pairs Driver: Parallel Lines (2006), a divisive entry in a flagship open-world racing series, with the inaugural Far Cry (2004), a genre-defining first-person shooter that spawned a billion-dollar franchise. This review does not treat the compilation as a curated experience—the two games exist in isolation, with no narrative or mechanical link. Instead, it examines the pack as a historical artifact, a bundle that encapsulates the mid-to-late 2000s ambitions and anxieties of two major Ubisoft-owned studios (Reflections Interactive and Crytek, respectively). The thesis is clear: this compilation’s value lies not in synergy, but in its stark illustration of two pivotal franchises at inflection points—one attempting a gritty, period-specific reinvention, the other establishing a template for emergent, systemic sandbox combat—both ultimately surpassed by their own sequels and the evolving industry. Its legacy is that of a convenient, if historically fascinating, footnote.

Development History & Context: Separate Journeys, Converging Catalog

The origins of this pack are purely utilitarian, born from Ubisoft’s post-2007 acquisition of both the Driver and Far Cry intellectual properties and its strategy to maximize back-catalog sales on PC.

Driver: Parallel Lines was developed by Reflections Interactive, the Newcastle-based studio synonymous with the Driver series. Following the critical and commercial stumble of Driv3r (2004), Reflections sought a return to form. Their vision was a deliberate shift: a “harder,” more mature tone set across two distinct time periods (1978 and 2006). Technologically, the game ran on a heavily modified version of the Driv3r engine, struggling with the era’s transition to true next-gen hardware. It was a last-gasp effort to recapture the series’ PS2/Xbox-era glory on those very platforms, alongside a PC port, before the franchise underwent a significant hiatus. The game’s development was constrained by the need to build upon existing, aging tech, leading to a visually inconsistent product—the 1978 segment’s grimy, film-grain aesthetic was a deliberate stylistic choice partly born of technical limitation.

Far Cry (2004), developed by Crytek and published by Ubisoft, was a watershed moment. It emerged from Crytek’s CryEngine, a showcase for cutting-edge PC graphics (notably vegetation rendering and large, open environments). Its development was defined by a then-radical philosophy: a vast, open-ended tropical island where players could tackle objectives in multiple ways, leveraging stealth, explosives, or brute force. The context was the rise of the immersive sim and the FPS’s exploration of sandbox design. Crytek’s vision was one of player agency within a beautiful, hostile world, a concept so potent it defined the series’ identity long after Crytek sold the Far Cry IP to Ubisoft.

By 2010, Ubisoft’s catalog strategy involved repackaging these now-established titles for the broader Windows PC market. The Action Pack was not a remastered or enhanced edition; it was a straightforward compilation of the existing PC ports, bundling them together for a budget price during an era where digital storefronts like Steam were gaining dominance but retail DVD-ROMs still held sway.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Revenge and Revolution in Separate Universes

The narratives of the two games are thematically and tonally opposed, highlighting their distinct developmental purposes.

In Driver: Parallel Lines, the narrative is a neo-noir revenge thriller structured across 28 years. The protagonist, TK (“The Kid”), is a wheelman framed for murder in 1978, serving a 28-year sentence before his release in 2006 to exact vengeance on the crew that betrayed him. The story is explicitly structured as a two-act play: Act I (1978) establishes TK’s rise and fall in a grimy, Taxi Driver-esque New York, while Act II (2006) shows a changed city and a hardened TK hunting his now-powerful enemies. The themes are classic noir—betrayal, the corruption of time, the moral ambiguity of a criminal anti-hero—filtered through a car-centric lens. Dialogue is sparse, functional, and often cliché-ridden, serving the plot rather than character depth. The thematic core is the cyclical, inescapable nature of violence and revenge. The switch from 1978 to 2006 is not merely cosmetic; it’s a metaphor for TK’s lost innocence and the soulless modernization of his world. The narrative’s greatest weakness is its disjointed execution; the 28-year jump leaves a gaping void in TK’s psychology, and the 2006 story feels like a generic, violentvengeance tale compared to the more atmospheric setup of the past.

In Far Cry (2004), the narrative is a lost-in-paradise survival tale. Jack Carver, a former special forces soldier turned smuggler, is shipwrecked on a tropical archipelago populated by hostile mercenaries and a mysterious, genetically-enhanced native population. The story is a linear B-movie plot—find the journalist, escape the island—but its genius is thematic escalation. It begins as a survival story against mercenaries led by the charismatic madman, Krieger. It then pivots into a sci-fi horror confrontation with Krieger’s mutant “Trigens.” The central theme is the violation of nature—Krieger’s experiments represent scientific hubris unleashing chaos upon a pristine, deadly environment. The dialogue is functional and often campy, but the environment itself tells the story: the shift from sun-drenched beaches to foggy, Trigen-infested valleys mirrors the descent from survival into nightmare. Unlike Parallel Lines’ personal revenge, Far Cry’s stakes are ecological and existential, pitting man against a mutated wilderness. The narrative serves primarily as a scaffold for the systemic, emergent gameplay, which was the true revolutionary aspect.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Distinct Pillars of Their Genres

The two games represent fundamentally different gameplay philosophies, a chasm the compilation does nothing to bridge.

Driver: Parallel Lines is a vehicular action game with on-foot segments. Its core loop is driving: missions involve high-speed chases, timed deliveries, escapes, and racing across a scaled-but-authentic recreation of New York City. The driving model is weighty and arcade-oriented, emphasizing handbrake turns and dramatic collisions. The infamous “Reflections Damage Model” (cars deform realistically but drive almost normally) is in full effect. On-foot gameplay is a notable regression from Driv3r; swimming and climbing are removed. Gunplay is clunky and cover-based, a clear weak point. The progression system is non-existent; cars are mission-gated or purchased with money earned from missions, but there is no skill tree or character upgrade. The “28-year gap” manifests gameplay-wise in the 2006 era’s addition of more powerful, modern cars and slightly improved weaponry. The innovative—if flawed—system is the “Heat” mechanic: police pursuit levels that escalate aggressively, forcing the player to lose their wanted level by changing cars, finding spray shops, or simply outrunning the relentless, omnipresent police AI. It’s a tense, frustrating, and often brilliant distillation of classic Driver tension, though it sometimes breaks due to the AI’s supernatural awareness.

Far Cry (2004) is a first-person shooter with systemic open-world sandbox elements. Its core loop is the “go-to-point, clear-area, proceed” mission structure within a vast, beautiful island. The revolutionary system was its physics and AI-driven world. Enemy patrols followed set routes but could be disrupted. Vegetation was not just scenery but tactical cover—a player could lie prone in tall grass and remain unseen. The “fire propagation” system allowed flames to spread realistically, creating emergent tactical opportunities (or disasters). Weapon and vehicle handling were functional but unremarkable for the time. Progression was mission-based; new weapons and gear were unlocked upon completing objectives, but there was no persistent character upgrade. The most significant systemic element was the “outpost” dynamic: many areas were controlled by mercenaries. Clearing an outpost (by stealth or assault) often resulted in it staying cleared, providing a sense of persistent change in the world—a precursor to later Far Cry games’ “liberation” mechanics. Its flaw was in the late-game “Trigen” sections, which abandoned the open-ended FPS for claustrophobic, linear horror corridors, a jarring and often hated shift in pacing.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Contrasts in Atmosphere

The two games use their audiovisual presentation to create wildly different, yet equally iconic, moods.

Driver: Parallel Lines’ world is a love letter to and critique of urban decay. The 1978 New York is rendered in a desaturated, grainy, film-noir palette. It’s dirty, gritty, and feels authentically period, with a killer soundtrack of 70s funk and rock (licensed tracks are a highlight). The 2006 New York is brighter, shinier, and more pluralistic, but feels hollow and commercial. The art direction masterfully uses the time-jump to contrast a “authentic” past with a “soulless” present. The sound design is car-centric: the roar of engines, the screech of tires, the crunch of collisions are paramount. The on-foot soundscape is thin, with functional gunshots and pedestrian cries. The world-building is environmental storytelling: the change in architecture, billboards, and vehicle design tells the story of urban evolution, for better or worse.

Far Cry (2004) is a masterclass in lush, oppressive naturalism. Its island is a breathtaking blend of sun-drenched beaches, dense jungles, towering mountains, and murky swamps. The CryEngine’s vegetation rendering was unprecedented, creating a world that felt alive and immense. The art direction emphasizes a paradise corrupted: vibrant colors are later contrasted with the sickly greens and grays of Trigen territory. The sound design is immersive and environmental: crashing waves, distant animal calls, rustling leaves, and the ever-present, unsettling hum of insects. The music is minimal and atmospheric, letting the world’s sounds dominate. This is a world that is both beautiful and actively hostile, a character in itself. The “world-building” is less about narrative exposition and more about the player’s sensory experience of being lost in a vast, untamed ecosystem.

Reception & Legacy: Divergent Paths, One Bundled Fate

At launch, the titles’ receptions could not have been more different, and their legacies have evolved in opposite directions.

Driver: Parallel Lines received mixed-to-positive reviews at launch (circa 2006-2007). Critics praised its gritty 1978 atmosphere, fantastic driving physics, and tense police pursuit system. However, it was widely criticized for its weak on-foot combat, a simplistic and predictable story, and a jarring, poorly-executed jump to 2006 that felt like a different, lesser game. It was seen as a partial return to form for the Driver series but failed to recapture the magic of the original. Its legacy is that of a cult favorite and a fascinating “what if”. Many fans consider its 1978 segment one of the best-realized eras in the series, praising its focused, atmospheric narrative and driving challenges. It is remembered as the last traditional Driver game before the franchise’s long hiatus and the supernatural, possession-based gimmick of Driver: San Francisco (2011). Its influence is subtle, mostly in the way subsequent open-world driving games handled police AI and period aesthetics.

Far Cry (2004) was a critical darling and commercial success. It won multiple “Game of the Year” awards for its revolutionary open-ended FPS design, stunning graphics, and emergent gameplay. Its legacy is monumental: it established the “Far Cry” formula—open world, outpost clearing, first-person traversal, and a charismatic villain—that would define the franchise under Ubisoft Montreal, even as Crytek moved on to create Crysis. It directly influenced the design of countless open-world shooters, from Just Cause to Crysis itself, and its “systemic sandbox” philosophy can be traced into modern titles like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. The original is now seen as a pioneering, if dated, classic. Its AI and systemic design were groundbreaking, even if its graphics and gunplay have been surpassed.

The Action Pack itself (2010) was a retail afterthought. It received virtually no critical attention; it was a budget compilation with no enhancements, released into a market increasingly moving to digital distribution. Its “reception” is defined by its absence from discourse. Its legacy is purely archival: it serves as a convenient snapshot for collectors and historians, physically binding two pivotal but unrelated titles from Ubisoft’s formative 2000s portfolio. It highlights how Parallel Lines was a series at a creative dead-end (leading to a 5-year hiatus) while Far Cry was a franchise just beginning its explosive growth.

Conclusion: A Historical Bundle, Not a Cohesive Experience

Action Pack – Driver: Parallel Lines + Far Cry is not a game to be experienced as a unified whole but as two separate historical documents. Driver: Parallel Lines stands as a poignant, beautifully atmospheric, but mechanically uneven elegy for the classic Driver formula. Far Cry (2004) stands as a revolutionary landmark whose Systems-first design reshaped the FPS genre. The compilation does them a disservice by forcing them into the same box without context or enhancement.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, this pack is a minor thread. Its primary value is pedagogical: it allows one to hold in their hands (or install on their hard drive) the divergent paths of two studios—one (Reflections) looking backward with noir-tinged nostalgia, the other (Crytek) looking forward with technological bravado—both under the expanding umbrella of Ubisoft. For the historian, it’s a tangible artifact of the mid-2000s bundling strategy. For the player, it’s a convenient way to acquire two historically significant games at a low cost. The verdict is not on the pack’s quality, but on its identity: it is a curio, a time capsule, and a testament to the fact that even within one company’s catalog, the stories of innovation and revival are never told in the same voice. Its place in history is that of a silent witness to two franchises’ pivotal moments, bundled together for convenience, forever telling two different stories.