- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Brodaroda Software

- Developer: Brodaroda Software

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Shooter

Description

After Burner 3D is a freeware 3D remake of the classic arcade rail shooter After Burner. Players pilot an F-14 Tomcat fighter jet, launching from an aircraft carrier and automatically advancing through stages while steering to shoot down waves of enemy planes using a vulcan cannon with unlimited ammo and limited missiles, recreating the fast-paced, intense aerial combat of the original in a three-dimensional environment.

After Burner 3D Reviews & Reception

squakenet.com : So, without a doubt the game has the same arcade feel of the original

After Burner 3D: Review

Introduction: A Forgotten Homage in the Shadow of a Legend

In the pantheon of arcade classics, few games command the reverence of Sega’s 1987 masterpiece After Burner. A pinnacle of “taikan” (body sensation) cabinet design, it fused Yu Suzuki’s visionary direction with groundbreaking sprite rotation and a hydraulic cockpit that made players feel the G-forces of aerial combat. Yet, for every iconic original, there exists a shadow—a testament to its influence in the form of fan-driven recreations. After Burner 3D (2003), developed by the enigmatic Brodaroda Software, is precisely such a shadow: a freeware, Windows-based 3D remake that captures the spirit of Suzuki’s rail shooter while inevitably stumbling under the weight of its own modest ambitions and the towering legacy it seeks to emulate. This review will dissect After Burner 3D not merely as a standalone game, but as a fascinating cultural artifact—a sincere, if flawed, love letter to the arcade golden age, examining its place at the complex intersection of fandom, preservation, and the enduring challenge of translating visceral cabinet-based magic to a keyboard and monitor.

Development History & Context: The Independent Dev vs. The Sega AM2 Juggernaut

The Original’s Impossible Shadow: To understand After Burner 3D, one must first confront the sheer scale of the 1987 original. Conceived by the legendary Yu Suzuki at Sega’s Studio 128, After Burner was born from a mandate to create Sega’s first “true blockbuster.” Developed in a separate building under a new “flextime” system, it was a closely guarded secret. Suzuki’s initial vision, inspired by Hayao Miyazaki’s Laputa: Castle in the Sky, pivoted to the globally palatable, adrenalin-fueled aesthetic of Top Gun. Technologically, it was a marvel: the first Sega game developed on PC-98s, it conquered the immense challenge of real-time sprite and surface rotation on the Sega X-Board hardware. The resulting deluxe hydraulic cabinet—complete with tilting, rotating cockpit, seatbelt, and stereo speakers—was an engineering and financial commitment that cost £4,000 (approx. $18,000 today) in the UK. This was not just a game; it was a spectacle, a destination.

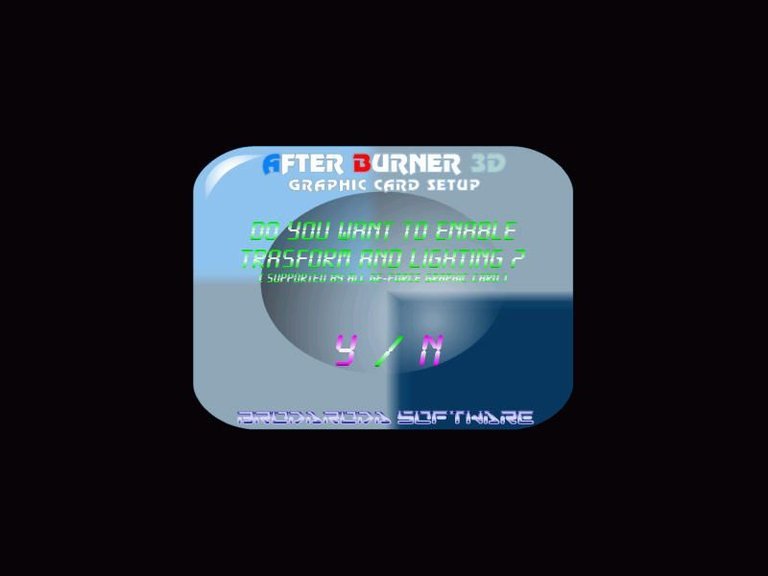

Brodaroda’s Modest Hangar: Fast forward to 2003. The context for After Burner 3D could not be more different. Brodaroda Software is a name that leaves virtually no footprint in industry records—a quintessential indie or hobbyist operation operating in the nascent era of accessible 3D game engines and widespread internet distribution. The “3D” in the title is both a descriptor and a point of differentiation: while the original used clever 2D sprite scaling to simulate 3D depth, After Burner 3D commits to fully polygonal environments. This was a logical evolution for a homebrew remake, leveraging the computational power of early-2000s PCs to tackle a problem the original solved with trickery: true three-dimensional space. The business model is antithetical to Sega’s: it is pure freeware, a public domain passion project with no commercial intent. The technological constraint shifted from creating cabinet motion to faithfully simulating the gameplay of an on-rails shooter with primitive 3D assets and keyboard controls. The “Studio 128” of its day was likely a single developer’s bedroom.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Excuse Plot, Perfected and Parred Down

The Original’s Cinematic Skeleton: The 1987 After Burner famously operates on an “Excuse Plot” (as TV Tropes accurately notes). The setting is a vague conflict against an anonymous, unidentified enemy force. The only narrative beats are the refueling/landing sequences between stages, which Suzuki added for variety. There is no story, no characters, no dialogue. The theme is pure, unadulterated momentum and skill. The “SEGA Enterprise” aircraft carrier is a iconic stage, not a narrative hub. Any plot about rescuing a damsel or stopping a nuclear launch is a later addition from some console ports (notably hinted in After Burner II and fully realized in After Burner Climax and Black Falcon), but the arcade core remains narrativevacuous.

After Burner 3D: The Minimalist’s Minimalist: In this regard, After Burner 3D is utterly orthodox. It presents no narrative whatsoever. There is no introductory text crawl, no mission briefing, no character chatter, and no ending sequence beyond the cessation of combat. The game begins with a launch from an aircraft carrier (a direct lift from the original’s iconic opening) and ends when the player’s lives are depleted. The “thematic deep dive” is therefore a dive into nothingness. Its theme is a purer, even more austere form of the original’s: it is about the loop. The pre-flight checklist, the roar of the engines (simulated by sound), the dance of evasion and attack, and the inevitable fiery demise. Any deeper meaning must be projected by the player onto the abstract skies and geometric enemy formations. It is a game as pure process, a zen koan of arcade action. Where later series entries like Climax embraced hammy voice acting and globe-trotting stakes (“Brave Fangs, Z is preparing the launch of a nuclear weapon…”), After Burner 3D retreats to the silent, hyper-focused essence of the 1987 cabinet experience.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Autonomy and the Illusion of Flight

The On-Rails Covenant: The foundational, non-negotiable rule of After Burner is autonomy. The player’s F-14 Tomcat (or a facsimile thereof) hurtles forward at a fixed, breakneck speed. Control is limited to horizontal and vertical steering via the arrow keys (in the fangame) or flight stick (in the arcade original). This design choice is genius in its simplicity: it removes the cognitive load of throttle management and complex navigation, forcing all player attention onto evasion and targeting. The core loop is a hypnotic trance of weaving through enemy bullet patterns and missile swarms, punctuated by the satisfying thwump of the vulcan cannon and the lock-on beep of a heat-seeker.

Weaponry: Unlimited vs. Limited: Both the original and After Burner 3D employ a dichotomous arsenal:

1. Vulcan Cannon: An endless stream of machine-gun fire. This is the workhorse, used for popping nearby enemies and clearing immediate threats. It requires no resource management.

2. Heat-Seeking Missiles: A limited stock (replenished after some stages in the original; specifics for the fangame are unclear but it adheres to the “limited” design). These are the strategic tool, used for taking out tougher, distant, or clustered enemies. The act of firing one is a deliberate, high-reward moment.

After Burner 3D‘s handling of this system is its most critical fidelity test. The MobyGames description states the fighter “flies forward automatically… with two additional keys for each weapon type.” This suggests a direct, unadorned translation: one key for gun (though it may be automatic), one for missile. The challenge, as noted in the Hrej! review, is the camera. The source criticizes the “not quite optimized” camera that often presents an “awkward angle,” fundamentally altering the feel of evasion. In the original, the tightly framed, dynamic camera was part of the spectacle, moving with the plane. In the fangame, a static or poorly programmed camera becomes a gameplay obstacle, making the “simple” task of steering feel unfair and artificially difficult. This is the central flaw: the fangame replicates the rules but struggles to replicate the cinematic feel that made those rules enjoyable.

Progression and UI: There is no character progression in the traditional sense. The plane’s capabilities are static from start to finish. “Progression” is purely the player’s skill improvement and the gradual increase in enemy density and complexity across the 18 stages (preserved from the original). The UI is barebones: a life counter, a missile indicator, and a score. The MobyGames entry confirms no mention of a lock-on reticule or other assists, placing it in the “purist” but potentially frustrating camp compared to later series entries like Climax which introduced a “Burst” slow-motion lock-on system.

Innovation vs. Flaw: After Burner 3D‘s sole mechanical “innovation” is the shift to true 3D graphics. However, this is a double-edged sword. The original’s 2D sprites on scaling planes created a clean, readable, and high-performance visual language. Early-2000s software 3D rendering often resulted in messy, textureless polygons and a lack of clarity in depth perception, directly impacting gameplay. The Hrej! review’s comment on enemies arriving “in formations and in larger numbers” while the player is “alone against everything” highlights how the original’s sprite-based clarity helped manage this chaos. The fangame’s 3D models, without sophisticated lighting or particle effects, can make threats harder to discern, amplifying the difficulty in a way that feels like a step backward.

World-Building, Art & Sound: From Hydraulic Immersion to Desktop Simulation

The Original’s Sensory Assault: Sega AM2’s 1987 achievement was total sensory immersion. The world was a pastiche of Suzuki’s travel magazine-inspired vistas: oceans, canyons, deserts, and cities rendered in vibrant, high-contrast sprite art. The soundtrack by Hiroshi Kawaguchi is iconic—a driving, synth-rock score with memorable melodies like “After Burner” and “Red Out.” But the true world-building happened in the cabinet. The hydraulics, the rumble, the seatbelt tightening—this was the “world” the player inhabited. The sound design, pumped through head-level speakers, was meant to be enveloping.

After Burner 3D‘s Digital Facsimile: Brodaroda’s world is built on a simple 3D engine. The Squakenet description calls it “not that detailed but at any rates it is not ugly either.” This is a generous assessment. Likely featuring low-poly terrain, basic textures, and simple box-like enemy models, the game prioritizes performance and scale over artistic detail. The atmosphere is one of digital abstraction. The “ocean” might be a blue plane with a reflective sheen; “canyons” are coloured walls. It lacks the original’s bold, graphical identity.

The sound design is equally rudimentary. There is no indication of an original soundtrack; it likely uses generic shooter loops or, more probably, silent-reliant gameplay where the only audio is the repetitive pew-pew of the vulcan and the occasional missile launch. The complete absence of the hydraulic feedback loop is the fatal gap. What was a full-body experience is reduced to finger dexterity on a keyboard. The “world” is now just a visual backdrop on a monitor, its lack of immersion directly correlated to its status as a freeware PC title. The Softonic review notes that “the pace is a bit slower” than the original—a damning critique for a series defined by its white-knuckle speed. This slowdown is likely a byproduct of rendering software 3D on generic hardware, further breaking the illusion.

Reception & Legacy: A Curios in the Franchise Crypt

Contemporary Reception (2003-2009): After Burner 3D existed in the deep corners of freeware/shareware sites and early digital distribution platforms. Its reception, as recorded on MobyGames, is sparse but telling: an aggregate critic score of 71% from three sources (Abandonia Reloaded 74%, Hrej! 70%, Softonic 70%). This is a competent, “B-minus” score for a niche project.

* The Abandonia Reloaded review is the most positive, framing it as a fun “old school shooter” for those seeking a challenge or nostalgia.

* The Hrej! review is the most insightful, praising the “excellent audiovisual realization” and improvements over the developer’s earlier Taleban Attack, but crucially identifying the camera as the primary flaw that makes the game “quite difficult” and “unskillful.”

* Softonic acknowledges the slower pace but asserts it retains the “same feeling” as the original, requiring “concentration and quite a bit of skill.”

The single player rating (3.3/5) suggests passive curiosity but little passionate engagement. It was not a breakout hit, nor was it panned; it was a competent footnote appreciated by a tiny subset of arcade purists and preservation-minded fans.

Legacy Within the Series and Industry: In the vast, multi-decade history of the After Burner franchise—spanning arcade cabnets, home consoles, the Sega CD, the 32X, the 3DS, and modern HD updates—After Burner 3D is a ghost. It is not mentioned in official Sega retrospectives, franchise timelines, or scholarly works like The Sega Arcade Revolution. It has no influence on subsequent games. Its legacy is purely that of a fan-made preservation attempt. It represents the earliest wave of fan-driven remakes that would later become a staple of the indie and retro gaming scenes, predating the more polished, celebrated homebrew projects by years.

Its significance is therefore archaeological. It is a snapshot of what an independent developer in 2003 believed was essential to the After Burner experience: the on-rails flight, the F-14, the carrier launch, the vulcan/missile dichotomy, and a move to 3D. The camera flaw reveals the immense, often underestimated difficulty of translating a game built for a specific, immersive hardware environment into the abstract space of keyboard and mouse. It proves that the soul of After Burner was not just in its ruleset, but in its presentation—in the synergy between the visual perspective, the speed, and the physical feedback.

Conclusion: The Definitive Verdict

After Burner 3D is not a lost classic. It is not a forgotten gem. It is, instead, a valuable and revealing artifact of fan reverence. As a game, it is a technically competent but flawed simulation of a masterpiece. Its camera system cripples the core evasion gameplay, its graphics are simplistically dated even for 2003, and its lack of any audio spectacle or physical feedback leaves it feeling hollow next to the hydraulic titan it apes. The 71% scores are fair: it is a playable, sometimes enjoyable diversion for those who know what they’re getting into—a skeletal version of an experience that was, by design, never meant to be skeletal.

Its true worth lies in what it tells us about the After Burner mythos. It confirms that the series’ enduring appeal is rooted in a deceptively simple, brutally challenging gameplay loop that is extraordinarily sensitive to execution. The original’s genius was in wrapping that loop in an unprecedented package of sensory overload. After Burner 3D strips away the overload and reveals the loop for what it is: a razor-sharp, unforgiving test of pattern recognition and twitch reflexes that becomes significantly less fun when the view is obstructed and the world is mute. It stands as a silent monument to the fact that some arcade magic is inextricably bound to the cabinet, the coin slot, and the specific technological alchemy of its era. For historians, it is a must-study case. For players, it is a curiosity—a well-intentioned echo that proves the original’s voice was far louder than we might have remembered.