- Release Year: 2022

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Immanitas Entertainment GmbH, Split Light Studio Sp. z o.o.

- Developer: Split Light Studio Sp. z o.o.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements, Shooter, Survival horror

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 60/100

- VR Support: Yes

Description

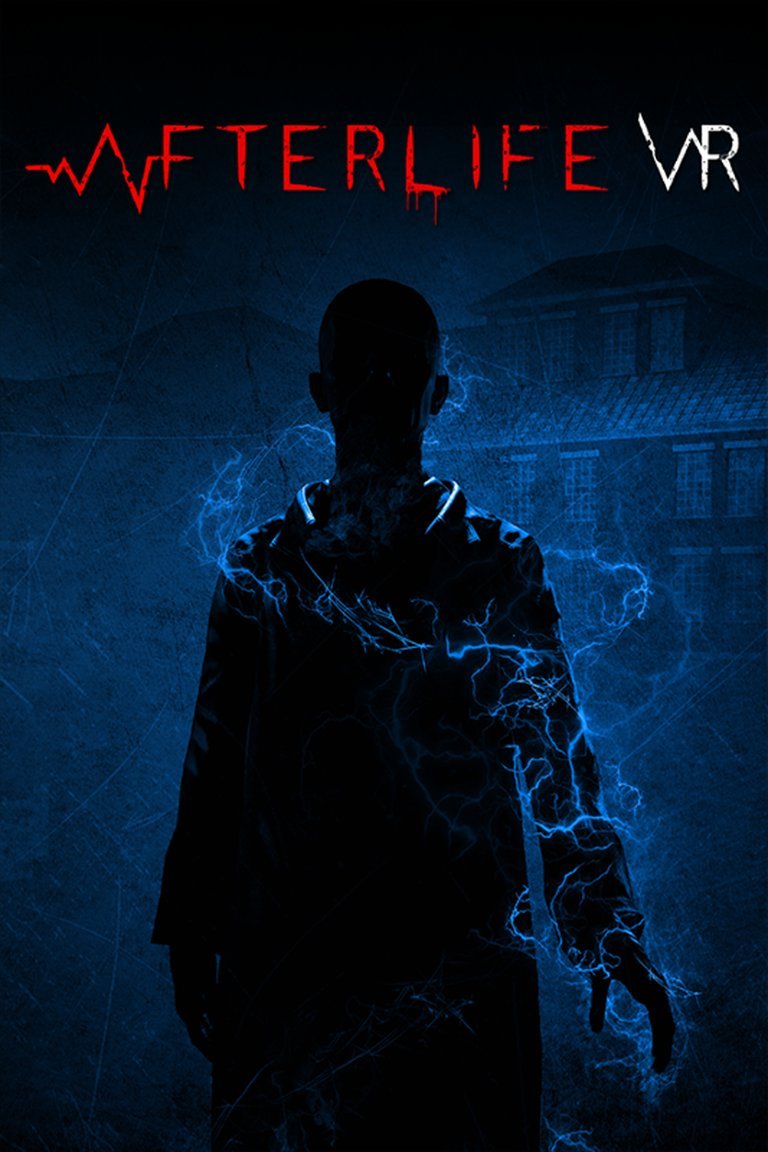

Afterlife VR is a first-person survival horror game built exclusively for virtual reality. You play as Adam Bernhard, a rookie police officer whose routine patrol leads him to the Black Rose mental hospital, where his sister is a patient. The facility is shrouded in mystery, with a history of missing patients and staff linked to a study on the ‘Indigo Children’ phenomenon. Armed with a firearm and psychokinetic powers, you must explore the terrifying asylum, solve motion-controlled puzzles, and confront the pure madness that lurks within its walls to uncover the horrifying truth.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Afterlife VR

PC

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

pushsquare.com (60/100): There is nothing brand new to look forward to in the title, but Afterlife VR effectively takes a blender to a number of horror tropes and settings, delivering a sufficiently worthwhile experience.

geekireland.com : Afterlife VR feels like a VR game that would have done very well on the original PSVR, but with the offerings coming out for the PSVR2 it feels stuck in the past.

Afterlife VR: A Relic of the VR Gold Rush

In the annals of virtual reality horror, a genre defined by its potential for unparalleled immersion and its susceptibility to cheap thrills, Afterlife VR stands as a fascinating artifact. Released in 2022 by Polish studio Split Light Studio, it is a game caught between two eras: the ambitious, often rough-hewn early days of consumer VR and the more polished, expectations-driven landscape of today. It is a title that promises the “true essence of terror” but ultimately delivers a competent, if unremarkable, journey into the dark that feels both nostalgic and dated.

Development History & Context

The Studio and the Vision

Split Light Studio, a relatively small developer, assembled a team of 19 credited individuals to bring Afterlife VR to life. The credits reveal a team with prior experience on titles like Whispers of a Machine, Stygian: Outer Gods, and The Beast Inside, hinting at a pedigree in narrative-driven and horror-adjacent projects. Their vision, as stated on their website and Steam page, was clear: to create a “deeply immersive horror game built from the ground up for VR” that leveraged the unique capabilities of motion controllers to foster a chilling, interactive experience.

The Technological and Market Landscape

Afterlife VR entered Early Access on PC in May 2022, with a full release following in September of that year. It was built using Unreal Engine 4, with PhysX handling physics, a common and powerful combination for the time. Its release came not during the initial “gold rush” of 2016-2018, but in a more mature VR market where players had been conditioned by higher-budget experiences like Half-Life: Alyx and Resident Evil 4 VR. However, as noted by critics, its design philosophy and technical execution seemed firmly rooted in that earlier, more experimental period. The game was later ported to PSVR2 in April 2023, a move that would starkly highlight its technical limitations against the capabilities of newer hardware.

The Gaming Landscape

The game entered a crowded field of VR horror titles, many of which also used the trope of the abandoned mental asylum. Its challenge was to distinguish itself not through a massive budget, but through clever mechanics—specifically its promised use of “psychokinetic powers”—and a compelling narrative hook involving the “Indigo Children” phenomena.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot and Characters

You play as Adam Bernhard, a rookie police officer with a curiously unplaceable European accent (voiced by Andy Mack, a veteran with credits on 39 other games). During a routine night patrol, Adam receives a call that draws him to the Black Rose mental hospital, a facility where his younger sister, Allison, was recently committed. Upon arrival, he finds the institution in a state of derelict abandonment, a stark contrast to the active facility he expected.

The narrative unfolds through environmental exploration, notes, and Adam’s constant, often overly instructive, internal monologue. The central mystery involves the disappearance of patients and staff, which Adam soon connects to a “groundbreaking study about the Indigo Children phenomena”—a reference to the pseudoscientific belief in a generation of children with supernatural, often psychic, abilities. The plot attempts to weave a tale of personal tragedy (the search for a sister) with a larger conspiracy of scientific hubris and supernatural horror.

Themes and Execution

Thematically, Afterlife VR treads familiar ground: the corruption of scientific inquiry, the thin line between genius and madness, and the horror of institutional neglect. The setting itself—the decaying mental hospital—is a classic Gothic trope representing a fractured mind and a forgotten past.

However, the execution is where the narrative stumbles. Critics universally panned the voice acting and the repetitive, hand-holding dialogue. Adam’s constant narration, telling the player exactly where to go and what to do next (“I should check the registration desk”), severely undermines the sense of discovery and tension. It treats the player as a passive participant in his story rather than an active explorer of the world. The story, while possessing an intriguing kernel with the Indigo Children concept, ultimately plays out in a predictable manner, failing to fully capitalize on its more unique ideas.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loop

The core loop of Afterlife VR is a straightforward blend of exploration, simple puzzle-solving, and limited combat. Players navigate the linear, corridor-based environments of the Black Rose hospital, searching for keys, keycodes, and items to progress. The game is relatively short, with most playthroughs lasting around two hours.

Interaction and Immersion

This is where the game’s “gold rush era” design is most apparent. While built for motion controllers, the interactions are often disappointingly canned. As noted in reviews, opening a door isn’t a matter of physically grabbing and pulling it; instead, interacting with it triggers a pre-set animation. The same is true for crouching and the notoriously finicky process of reloading your flashlight with batteries. This lack of physical fidelity breaks immersion constantly, making the world feel less like a place you inhabit and more like a series of buttons to press with your controllers.

Puzzle Design

The puzzles are largely environmental and inventory-based. The game promises “innovative puzzle design, taking advantage of both the motion controllers and the protagonist’s telekinetic abilities.” While the telekinesis is a novel idea, it is introduced late and underutilized, featured in only a handful of puzzles. Most brainteasers involve finding codes or placing objects in the correct location, and their difficulty is often trivialized by Adam’s incessant hints.

Combat and Progression

Combat is a minor part of the experience. Players eventually acquire a handgun and their psychic abilities, which can be used to dispatch the game’s enemies: shuffling, bald “patients” who often engage in disturbing self-harm. Reviews found the gunplay to be surprisingly functional, if simplistic, but noted a strange imbalance in resources—ammo was plentiful, while flashlight batteries were frustratingly scarce. The telekinetic combat feels like an afterthought, lacking impact and strategic depth. A unique mechanic involves a watch that displays your heart rate, which must be managed with injections of medicine to avoid a game over, a system that, while interesting, is never fully explored or developed.

UI and Inventory

The inventory system is described as “finicky.” Items are stored on a virtual belt, but retrieving them, especially during tense moments, can lead to clumsy controller clacking. The UI is functional but lacks polish, contributing to the overall feeling of a janky, earlier-generation VR experience.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Black Rose Hospital: A Setting of Decaying Horror

The art direction is arguably the game’s strongest asset. The Black Rose mental hospital is rendered in a palette of grimy grays, oppressive shadows, and sickly greens. The environmental artists successfully created a palpable sense of decay and abandonment. As reviewer Eric Hauter noted, the environment feels authentic, eerily mirroring the real-world decay of abandoned institutions. Moldy food, overturned furniture, bloodstained walls, and medical debris sell the setting effectively.

Atmosphere and Sound Design

The atmosphere is heavily reliant on sound design, which is consistently praised across reviews. A persistent, low bassy hum permeates the facility, punctuated by distant screams, rattling pipes, and the unsettling noises of the enemies. This audio landscape does the heavy lifting in creating a sense of dread, often being more effective than the visual jump scares. The soundtrack, while not particularly memorable, services the tension well.

Visual Fidelity and Technical Performance

Visually, the game is a mixed bag. Environmental textures and lighting are competent and effectively creepy, especially when paired with the PSVR2’s OLED screens. However, character models and animations are stiff and dated, breaking the illusion during encounters. The technical performance, particularly on PSVR2, was a significant point of criticism. Reviews cited frequent frame rate drops, stuttering, and the use of a jarring bright blue out-of-bounds grid that could induce nausea. These issues were glaring on the powerful new hardware, marking the game as a less-than-optimal port.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Reception

Afterlife VR garnered a lukewarm-to-mixed reception. It holds a “tbd” Metascore due to a lack of critic reviews, but the existing critiques paint a consistent picture:

* Gaming Nexus (7/10): Found it “creepy enough in a low-budget, cookie-cutter sort of way” and worth its budget price.

* Push Square (6/10): Praised its atmosphere and sound but criticized its clunky interactions and unoriginality.

* Geek Ireland: Gave a more negative assessment, calling it a disappointing relic with performance issues.

The consensus was that it was a passable, short horror experience for its low price point (around $15), but it failed to innovate or meet the technical standards expected of newer VR platforms.

Legacy and Influence

Afterlife VR‘s legacy is minimal. It did not break new ground nor did it become a cult classic. Instead, it serves as a historical marker—a representative example of the mid-budget, tropish VR horror games that flooded the market in the early 2020s. It demonstrates both the enduring appeal of the asylum setting and the common pitfalls of VR development: over-reliance on jump scares, underbaked mechanics, and a failure to fully embrace the physical interactivity that defines the medium’s potential. Its most lasting impact is perhaps as a cautionary tale for how older VR design sensibilities can clash with the capabilities and expectations of modern hardware.

Conclusion

Afterlife VR is a game of conflicting identities. It is a title built with clear intent and a genuine understanding of horror atmosphere, yet it is hamstrung by technical limitations, dated design choices, and a narrative that fails to trust the player’s intelligence. It is, as multiple reviewers stated, a game that would have felt more at home on the original PSVR or Oculus Rift, where its janky interactions and low-budget scares might have been more readily forgiven.

For the VR horror completist on a budget, there are two hours of moderately effective chills to be found within the decaying walls of the Black Rose hospital. Its sound design and art direction create a suitably oppressive mood. However, for most players, especially those with access to the PSVR2’s more advanced library, Afterlife VR feels like a step backward. It is not a bad game, but it is an unremarkable one—a ghost from VR’s past that reminds us how far the medium has come, rather than a specter pointing toward its future. Its definitive place in video game history is as a footnote: a perfectly adequate example of the VR horror genre’s formative, and often forgettable, adolescence.