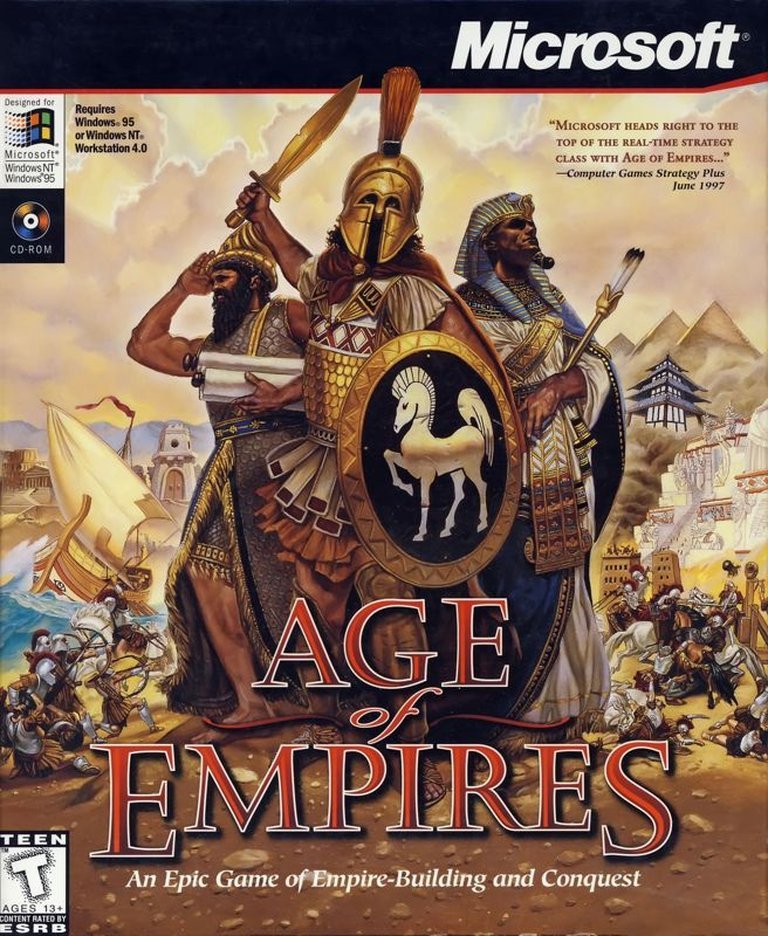

- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Learning Company, The, MacSoft, Mattel Interactive Deutschland GmbH, Microsoft Corporation

- Developer: Ensemble Studios Corporation

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Base building, Real-time strategy, Resource Management, Technological progression, Unit production

- Setting: Africa, Classical antiquity, Egypt (Ancient), Europe, Historical events, Middle East

- Average Score: 83/100

Description

In Age of Empires, players guide a tribe through four historical Ages—from the Paleolithic to the Iron Age—by managing resources like food, wood, stone, and gold to build structures, develop technology, and wage real-time warfare across ancient settings in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Age of Empires

PC

Age of Empires Free Download

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (83/100): Anyone who appreciates a solid, lovingly-crafted work of design should appreciate the overall quality of this product.

imdb.com : From long before “Et tu, Brute?”

gamespot.com : This is not quite the game you hoped for. Even worse, it has some definite problems.

Age of Empires: Review

Introduction

Released in 1997 by Ensemble Studios and published by Microsoft, Age of Empires emerged as a revolutionary force in the real-time strategy (RTS) genre. At a time when RTS titles were dominated by science-fiction and fantasy settings like Warcraft II and Command & Conquer, Age of Empires dared to reimagine history, thrusting players into the role of ancient civilization leaders. Its ambition was audacious: to merge the empire-building depth of Civilization with the visceral combat of Warcraft, spanning 12,000 years from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. Despite initial skepticism and technical flaws, the game carved an indelible legacy. This review deconstructs its historical significance, gameplay innovations, and enduring impact, arguing that Age of Empires laid the groundwork for a genre-defining franchise despite its imperfections.

Development History & Context

H3: The Vision of Ensemble Studios

Age of Empires was the brainchild of Ensemble Studios, a fledgling developer founded by Tony Goodman. Its core design team—Bruce Shelley (co-designer of Civilization), Rick Goodman, and Brian Sullivan—sought to create an RTS rooted in tangible history rather than fantasy. Their vision, as Shelley articulated, was to make history “accessible and fun,” drawing inspiration from Sid Meier’s Civilization while injecting real-time combat mechanics. This “Civilization meets Warcraft” ethos aimed to appeal to both strategy enthusiasts and casual players by replacing aliens and orcs with pharaohs and legionnaires.

H3: Technological Constraints and Ambition

Developed under the working title Dawn of Man, the game utilized Ensemble’s proprietary Genie Engine, a 2D sprite-based system optimized for performance. Remarkably, the engine was coded predominantly in x86 32-bit assembly language (13,000 lines), enabling faster sprite rendering than competitors like StarCraft. This choice was pragmatic: the team prioritized smooth unit animations and large maps over 3D graphics. Despite these optimizations, the game faced significant hurdles. Pathfinding AI, in particular, proved stubbornly difficult to perfect, leading to units frequently getting stuck or behaving erratically. The development cycle spanned two and a half years with a team of 25, reflecting the ambition of creating a nuanced historical simulation within the rigid constraints of 1990s hardware.

H3: The Gaming Landscape of 1997

Age of Empires debuted in an RTS landscape saturated with high-fantasy titles. Warcraft II (1994) had defined the genre with its polished multiplayer, while Command & Conquer (1995) popularized the “build-and-destroy” loop. Age of Empires differentiated itself by embracing historical authenticity, offering 12 civilizations (Egyptians, Greeks, Assyrians, etc.) with unique architectural styles, units, and technologies. This shift resonated with critics and players weary of generic sci-fi, positioning the game as a breath of fresh air. Its announcement at E3 1996 generated buzz, promising a “thinking person’s RTS” that rewarded strategy over reflexes—a claim that would later fuel both acclaim and criticism.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

H3: Historical Authenticity vs. Gameplay Abstraction

Age of Empires eschews a linear narrative in favor of a sandbox-driven historical simulation. Its four campaigns—Egyptian, Greek, Babylonian, and Yamato—are loosely based on real events, such as the Trojan War or unification of Egypt. Yet the game prioritizes gameplay fidelity over historical rigor. Units like “Hoplites” appear in civilizations that never fielded them (e.g., Persians), and technologies are streamlined for strategic balance. This abstraction was intentional: as Shelley noted, “We’re not historians; we’re game designers.” The result is a world where players rewrite history, forging empires through choices rather than predetermined story beats.

H3: Themes of Progression and Civilization

The game’s core theme is progression, embodied by the four-age system (Stone, Tool, Bronze, Iron). Advancing through ages symbolizes humanity’s evolution from nomadic tribes to imperial powers, unlocking increasingly sophisticated units (from club-wielding villagers to war elephants). This mechanic reinforces the cyclical nature of history: empires rise and fall based on resource management, technological investment, and military might. Victory conditions—conquest, wonder-building, relic collection—echo historical goals, from Alexander’s conquests to the construction of the Pyramids. Notably, the game avoids glorifying war, emphasizing that survival hinges on balancing military expansion with economic stability—a subtle nod to the complexities of real-world civilizations.

H3: Character and Cultural Representation

While devoid of named protagonists, Age of Empires immerses players through cultural details. Units respond in their civilization’s ancient languages (e.g., Egyptian villagers in hieroglyphic-inspired tones), and buildings reflect authentic architectural styles (Greek columns, Mesopotamian ziggurats). Yet this authenticity is tempered by gameplay necessity. All civilizations share identical units beyond minor stat tweaks, leading to complaints that Shang villagers (half-cost) or Greek phalanxes were unbalanced. The tension between historical nuance and gameplay accessibility remains a defining trade-off, with the game’s lasting appeal rooted in its ability to make history feel tactile and malleable.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

H3: Core Resource and Economic Systems

The game’s foundation lies in its four-resource economy: food (hunting, foraging, farming), wood (logging), stone (mining), and gold (mining or trade). Resources are finite—trees don’t regrow, and mines deplete—forcing players to expand aggressively or trade strategically. This scarcity creates high-stakes decision-making: should you prioritize gold for trade or invest in stone for fortifications? Economic micromanagement is punishing; villagers must be manually reassigned as resources deplete, and farms require constant replanting. Critics hailed this as “realistic,” while others lamented it as tedious, especially given the absence of automation (e.g., no “gather at nearest mine” commands).

H3: Combat and Tactical Depth

Combat follows a rock-paper-scissors model: infantry beat cavalry, archers counter infantry, and siege units demolish buildings. Yet the system is undermined by pathfinding flaws and unit clumping. Armies often devolve into chaotic brawls, with siege units (e.g., catapults) disproportionately dominating late-game battles. Naval combat adds variety, with triremes bombarding shorelines and fishing boats supplementing food supply. The expansion The Rise of Rome (1998) later addressed balance issues (e.g., nerfing chariots) and introduced unit queues—a QoL improvement absent in the original. Notably, priests can “convert” enemies, enabling sneaky tactical reversals, though this mechanic was often overshadowed by brute-force rushes.

H3: Age Advancement and Technology

Advancing through ages is the game’s central progression loop. Researching the next age at the Town Center consumes massive resources (e.g., 800 food, 200 gold), creating pivotal moments where players risk stagnation to unlock elite units (e.g., iron swordsmen). The technology tree is vast, with over 100 upgrades spanning military, economic, and religious domains. Each civilization has exclusive technologies (e.g., Egyptian chariot bonuses), but many were deemed underpowered compared to the Shang’s villager cost reduction. This disparity fueled multiplayer imbalance, cementing the Shang as the dominant faction in competitive play.

H3: Innovation and Interface Design

Age of Empires introduced groundbreaking features:

– Random Map Generator: Creating infinitely replayable scenarios with varied terrain, resources, and chokepoints.

– Scenario Editor: Allowing players to design custom campaigns, a precursor to modern modding communities.

– Diplomacy: Basic alliances and trade mechanics, though rudimentary by today’s standards.

The interface, however, was divisive. The isometric view cluttered screens, and the lack of unit formations or waypoints forced players to micromanage every movement. The 50-population cap exacerbated these issues, limiting armies to token skirmishes. Despite these flaws, the game’s systems set a template for future RTS games, emphasizing player agency over scripted events.

World-Building, Art & Sound

H3: Historical Setting and Atmosphere

Age of Empires transports players to a meticulously researched ancient world. Maps range from African savannas teeming with lions and elephants to Mediterranean coastlines dotted with olive groves. Terrain elevation impacts combat—units gain advantages when attacking downhill—and rivers become natural barriers. The game’s historical authenticity extends to unit designs: Egyptian priests carry ankh staffs, Greek hoplites wear Corinthian helmets, and Babylonian archers wield composite bows. This attention to detail fosters immersion, even as gameplay liberties are taken (e.g., Persians using Greek architecture).

H3: Visual Direction and Art Style

The Genie Engine’s sprite-based graphics were cutting-edge in 1997. Units animate fluidly—villagers chop trees with rhythmic swings, and chariots leave dust trails in their wake. Environmental details like bird flocks and rippling water enhance realism. Critically, the game uses four distinct architectural sets (Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek, East Asian) for buildings, ensuring visual diversity between civilizations. While graphics pale by modern standards, the art style’s hand-painted charm and unit diversity (over 50 unit types) were lauded for their personality.

H3: Sound Design and Musical Score

Stephen and David Rippy’s score is a masterclass in historical ambience. Tracks blend period instruments—lyres, flutes, drums—with ambient sounds (crickets, ocean waves) to evoke ancient locales. Unit voice acting, though gibberish, feels authentic: Egyptian soldiers shout in Arabic-inspired tones, while Vikings roar in Old Norse. The soundscape is equally nuanced—wood clacks as villagers build, arrows whistle in flight, and war elephants trumpet with unnerving volume. This audio fidelity, combined with the visual artistry, creates an atmospheric experience that transcends its technical limitations.

Reception & Legacy

H3: Critical and Commercial Success

Age of Empires received a mixed-to-positive reception upon release. Aggregator scores averaged 83% (MobyGames), with praise for its historical depth and content. PC Player (Germany) awarded it 100%, calling it “a masterpiece for RTS fans,” while GameSpot criticized its AI as “Artificial Idiocy.” Commercially, the game was a triumph, selling over 3 million copies by 2000. It dominated sales charts in Germany (earning Gold and Platinum awards) and shipped 850,000 units worldwide within months of launch. The expansion The Rise of Rome added 1 million more sales, cementing the franchise’s viability.

H3: Influence on the RTS Genre

Age of Empires redefined historical gaming, inspiring countless successors:

– Empire Earth (2001) and Total War (2000) expanded the timeline.

– Rise of Nations (2003) refined its economic systems.

– Its sequel, Age of Empires II (1999), became the series’ apex, refining the formula with deeper civilizations and improved AI.

Even Blizzard acknowledged its impact; Warcraft III (2002) incorporated hero units inspired by AoE’s priest mechanics. The game’s legacy endures in modern titles like Civilization VI, which prioritizes historical narrative alongside strategy.

H3: Longevity and Modern Relevance

The original game’s flaws—poor pathfinding, population caps, and AI quirks—were addressed in later titles, but its core design remains influential. In 2018, Age of Empires: Definitive Edition brought 4K graphics, remastered audio, and improved netcode, introducing the game to a new generation. The Definitive Edition’s community-driven modding scene keeps the classic gameplay alive, proving that Age of Empires is more than a relic—it’s a living system still capable of thrilling players decades later.

Conclusion

Age of Empires is a flawed masterpiece. Its technical shortcomings—frustrating AI, imbalanced civilizations, and excessive micromanagement—prevent it from being a perfect game. Yet its ambition and execution revolutionize the RTS genre. By merging historical authenticity with accessible strategy, Ensemble Studios created a game that rewards thoughtful planning over zerg rushes, proving that history could be both educational and exhilarating. The series’ enduring success, spanning sequels, spin-offs (Age of Mythology), and remasters, attests to its foundational impact. As the first entry in a dynasty, Age of Empires stands as a testament to the power of vision—a game that didn’t just conquer the charts but rewrote the rulebook for historical strategy. Its place in gaming’s pantheon is secure: not just as a classic, but as a blueprint for how games can make history feel alive.