- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Genre: Action, Explorable platformer, Metroidvania

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Direct control, Metroidvania, Platform

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 69/100

Description

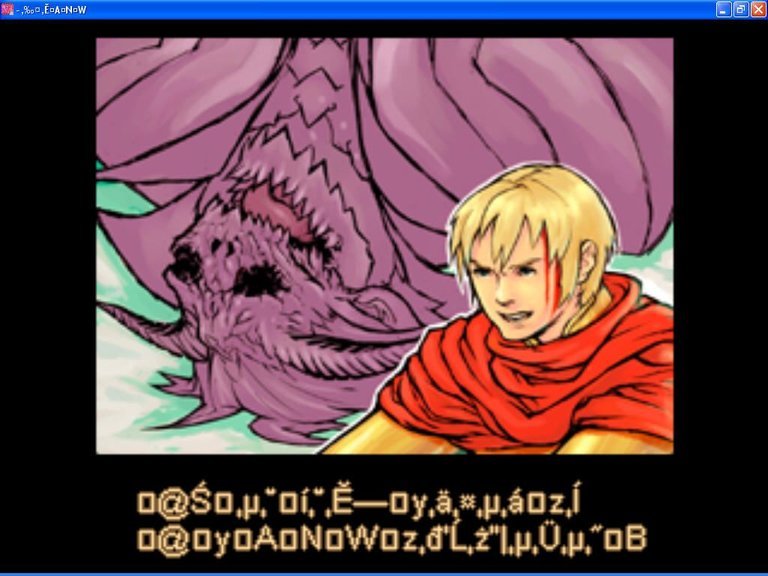

Akuji the Demon is a 2D side-scrolling Metroidvania platformer set in a dark fantasy labyrinth, where players control Akuji, a once-powerful pink vampire demon who has been stripped of his abilities and imprisoned after being defeated by a hero. Fueled by a desire for revenge, Akuji must navigate a sprawling, interconnected dungeon, recover his lost powers—such as running, fire attacks, and enhanced jumps—and collect scattered skulls to regain full strength. As abilities are reacquired, new pathways open up in both new and previously explored areas, deepening exploration. The game challenges players with obstacles, enemies, and multiple boss encounters, blending action-packed platforming with nonlinear progression in a haunting, scroll-based world.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Akuji the Demon

PC

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

howlongtobeat.com (75/100): Overall the game is short, sweet, and fun! Challenging platforming and decent bosses.

mobygames.com (79/100): Average score: 79%

myabandonware.com (82/100): Akuji the Demon is an excellent freeware platformer from Japan that puts many commercial titles to shame.

gamefaqs.gamespot.com (40/100): A degradingly simple Metroid-vania with challenge derived only from wrestling with the broken controls.

Akuji the Demon: Review

Introduction: Redefining the Villainous Perspective in a Forgotten Indie Gem

In a genre often dominated by paladins, knights, and chosen saviors, Akuji the Demon (2002) dares to turn the archetypal fantasy narrative on its tail by thrusting the player into the minions—or more accurately, the mouth—of a vanquished demonic overlord. Developed by the obscure Japanese indie designer E. Hashimoto (credited under the alias Buster), this freeware 2D platformer was born not from a major studio’s ambition but from a personal passion for Castlevania, Metroid, and the untapped potential of doujin (fan-made) games. Its central thesis is deceptively simple: What if the villain wasn’t just a boss to be slain, but a playable protagonist on a quest for redemption—or revenge—through the very dungeon where he was imprisoned?

At a time when the indie game scene was still in its digital infancy, and long before the era of Cave Story, Touhou Project, or Mega Man fan cartridges, Akuji the Demon stood as a surprising testament to what a single developer could achieve with limited tools but boundless creativity. While never achieving mainstream commercial success—its status as a free, modestly polished Windows application from early 2000s Japan kept it off retail shelves—it has endured as an underground cult hit, a beloved piece of abandonware, and a significant milestone in the evolution of “mini-Metroidvanias”.

This review presents a comprehensive, thematic, and mechanical deconstruction of Akuji the Demon, synthesizing feedback from over a decade of critical and player reception, developer quirks, genre conventions, and historical context. Our analysis will argue that Akuji the Demon is not merely a “great freeware game”—it is a deliberately self-aware, subversive, and often tongue-in-cheek reimagining of 8-bit and early-3D action-platformers, grounded in mechanical homage but elevated by narrative irony, visual novelty, and a surprisingly deep progression loop. It’s Castlevania meets Final Fantasy parody wrapped in the soul of a doujin meta-commentary on genre tropes. More than a curiosity, Akuji the Demon is a vital document of early indie game culture, DIY craftsmanship, and the democratization of game design—a tiny, pink, demonic masterpiece that punch far above its weight.

Development History & Context: The Indie Antecedent in a Pre-Steam Era

The Developer and the Doujin Scene

Akuji the Demon was created by E. Hashimoto, a Japanese developer operating under the handle “Buster”, a name that recurs across several other freeware titles from the early 2000s, including Hydra Castle Labyrinth and Guardian of Paradise. These works are prime examples of the doujin soft movement—a grassroots ecosystem of self-published games created by individuals or tiny collectives, distributed via Japanese BBS networks, personal websites, and fan BBS message boards, long before platforms like itch.io or Game Jolt.

Operating in the era of Windows 98/ME/XP, Hashimoto utilized what would now be considered rudimentary tools: DirectX 7-9 for rendering, sprite-based 2D graphics, and custom-built physics/algorithms for gameplay. The game was initially released exclusively in Japanese in January 2002, with its cyber-home at hp.vector.co.jp/authors/VA025956/game_akuji.htm, a now-dormant personal fan site typical of the Vector (now KENet) web hosting service popular among doujin creators.

Technological Constraints and Creative Solutions

Given the limited scope of personal freeware development in early 2000s Japan, the technological context was tightly bounded:

– Resolution: Capped at 1024×768, but typically rendered at 640×480 with zoom scaling, making use of pixel art clarity and avoiding performance strain.

– Engine: Custom-built engine using DirectDraw or Direct3D for graphics and DirectSound for audio, requiring users to have DirectX 9.0c+ and occasionally running into compatibility issues with modern Windows (e.g., missing d3drm.dll errors).

– Frame Rate/OS Compatibility: The game crashes on Windows 10+ without workarounds (e.g., dgVoodoo2, compatibility mode), and runs too fast on unshielded systems unless frame rate limiting is applied—a common issue with early DirectX games built for static CPU speeds.

Despite these limitations, Hashimoto achieved remarkably smooth animation, responsive hit detection (with caveats), and non-repetitive level design, all within a mere 3–5 MB download, a feat that reflects deep optimization.

The Gaming Landscape of 2002

To understand Akuji’s significance, we must situate it within the 2002 platforming and action landscape:

– Commercial Formats: On consoles, Metroid: Zero Mission was months away (2004), Castlevania: Circle of the Moon had just launched (2001), and the GBA era was shifting 2D platforming toward speed and polish.

– PC Indie Scene: The era pre-dates Steam (2003), Game Jolt (2006), and itch.io (2011). Distribution was messy: BBS, personal homepages, CD-ROMs at doujin festivals (Comiket), or Japanese freeware share sites like Vector.co.jp.

– “Weird Western” Influences: Western fans were just discovering I Wanna Be the Guy (2007) and Bloxors (2003), but doujin games were under the radar. Akuji’s closest Western analog might be early Zaxxon or Ninja Gaiden demos on NES homebrew—but with RPG progression.

Akuji the Demon was thus a hybrid artifact: a Japanese doujin game built with NES-generation aesthetics (limited colors, tile-based levels, boss patterns), GBA-era quality (smooth motion, non-linear exploration), and early PC freeware ambition (RPG mechanics, multiple difficulty levels, save systems).

Self-Aware Design & Meta Humor

As noted by Squakenet.com, Akuji the Demon is best understood as a “direct spoof” of Castlevania—yet not a caricature. It’s a game coded by someone who loved Castlevania, Metroid, and Final Fantasy too much, and thus sought to reconfigure their tropes into a new form. The parody emerges not in characters or plot, but in mechanical irony:

– The hero is the villain regaining powers in the dungeon he built? Yes.

– The “sword” is an absurdly large Final Fantasy-style blade wielded by a 32-pixel pink demon? Yes.

– The “boss” is a powerless knight who defeated the main character in a past life, now a king? Yes.

– The game ends with Akuji ascending to the surface, presumably to become the next final boss in some other game?

This meta-narrative layer—where the player experiences the enemy’s post-defeat journey—positions Akuji the Demon as one of the earliest examples of “enemy POV” gameplay, surpassing even Shadow of the Colossus (2005) in subverting hero/villain binaries. It’s Metroid, but from the egg-laying parasite’s side.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Reversal, Redemption, and Recontextualization

Plot Summary: The Villain’s Journey

The story unfolds in a nine-act structure spanning a single giant labyrinth:

1. Prologue (Prison): Akuji, a pink vampire demon, is sealed in a dark underground after being defeated by a knight who became king.

2. Origin Myth: The hero/Hero (literally named “Hero”) “defeated” Akuji and scattered nine magical stones—each containing one of Akuji’s powers—throughout the labyrinth.

3. Objective: Recover all nine stones, regain powers (run, jump, fire, fly, ghost, etc.), and escape to exact revenge on the Hero.

4. Structure: Each stone unlocks a new zone (Fiery Lava Cavern, Icy Tunnels, Floating Ruins, etc.), each with a unique environment, enemy set, and mini-boss.

5. Climax: The final stone unlocks the surface door; Akuji battles the Hero, then ascends, suggesting an infinite revenge cycle—he may become the next dark lord.

Note: The “magic stones” are often misinterpreted as “skulls” due to translation drift, but sources like MyAbandonware and the manual confirm they are crystal orbs, later referred to as “stones” in some patches.

Characterization & Identity

- Akuji: Despite being a “demon”, Akuji is cute, pink, androgynous, and goofy-looking—a critique of male, draconic, horned demon tropes. His design resembles Kirby meets Final Fantasy enemy sprites. His pinkness is deliberately at odds with the grim “dark labyrinth” setting, creating a juxtaposition that defines the game’s tone.

- The Hero / King: Never named beyond “Hero”, he is a silent figure seen in flashbacks. His defeat of Akuji is not heroic but pragmatic—he imprisoned Akuji to prevent further chaos. There’s no moral clarity: Who is evil? The demon who ruled, or the hero who stole his freedom?

- Enemies: Mostly comical, Kirby-esque blobs, weak skeletons, flying drones—not legions of darkness, but prison guards designed to test progress rather than embody evil.

Themes: Power, Identity, and the Burden of Legacy

The game explores three core themes:

1. Power Reclamation: Akuji’s journey is less about revenge and more about self-actualization. Each stone recovered is a piece of his identity restored. By game’s end, he’s not angry anymore—he’s awake, a being rediscovering his potential.

2. The Villain as Protagonist: By casting the player as the defeated villain, Hashimoto forces us to empathize with the “enemy”. We aren’t fighting for justice—we’re fighting for freedom, memory, and autonomy. The game asks: What does it feel like to be the villain in someone else’s hero story?

3. The Prison as Identity: The labyrinth isn’t just a setting; it’s Akuji’s psyche. Each zone reflects a lost power (speed = freedom, ghost = memory, fire = rage). The game becomes a metaphysical journey through a mind shattered and reassembled.

Narrative Parody & Ironic Design

The game undermines traditional fantasy tropes:

– “The Hero” is a literal label, not a character. He has no backstory, no family, no personality—just a trope reduced to a name. When Akuji fights him, it’s anticlimactic: the Hero is weak, unremarkable, almost pathetic. The joke: You lived in fear of this guy?

– “Evil” is Normalized: Akuji was “evil” because he ruled—but so did the previous king. The game implies the only difference is resistance to a new order.

– The Twist Ending: When Akuji exits, the sun shines on his face—he doesn’t laugh, conquer, or declare war. He walks into the world, curious. Is he reformed? Or is he the beginning of the next evil cycle?

This narrative grayness is Akuji’s greatest strength: it’s neither heroic nor villainous, but reflective.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Hybrid Evolution of Metroidvania Logic

Core Progression Loop: The “Mini-Metroidvania”

Akuji the Demon is best categorized as a “mini-Metroidvania”—a genre sub-type defined by:

– Non-linear exploration in a single, interconnected world (not a series of themed zones).

– Gated progression via ability-based access (e.g., jump high → access upper floor).

– Heavy backtracking, but with short, session-friendly playtime.

– RPG-like progression elements (levelling, stat increases).

Crucially, Akuji diverges from pure Castlevania or Metroid by:

– Lack of overworld map (unlike Metroid, there’s no automap).

– No weapon variety (only a sword and elemental shots, no sub-weapons).

– Light puzzle focus—mostly spatial navigation puzzles (“How do I reach that ledge?”) rather than contra-style traps.

Ability Unlock System: Power as Topology

Each of the nine magic stones grants a power that redefines spatial access:

| Power | Function | Unlocks |

|---|---|---|

| Run | Dash (press second direction) | Speed, precise jumps, through mud |

| High Jump | Double jump length | Upper platforms, ceiling secrets |

| Flame | Projectile/shoot | Break crates, kill weak enemies |

| Fly | Temporary floating | Over chasms, avoid hazards |

| Wall Slide | Grind on walls | Climb vertical tunnels |

| Wall Climb | Vertical ascent | Jump between floors |

| Super Jump | Charged leap | Ultra-high reach |

| Ghost | Turn invisible/phase through walls | Hidden rooms, secret paths |

| Stone | Transform into rock (damage immunity) | Break barriers, survive lava |

This hierarchical system ensures the player must backtrack—not repetitively, but productively. However, no single ability is essential for multiple routes, and the game lacks the density of interconnected pathways seen in Metroid: Zero Mission. It’s more like Ikachan—a loose web of paths with branches, not a true libyrinth.

Combat & Enemy Design

- Sword: Short range, fast swing, but no charge or combo system. Relies on timing.

- Fire/Elemental Shots: Limited ammo (mana stones), used for enemies immune to sword.

- Enemies: Low intelligence. Most follow tramline paths, fly back/forth, or teleport. No chasers or pincer attacks.

- Bosses: 9 mini-bosses (1 per zone) and 1 final boss (the Hero). They use simple patterns: shoot waves, charge, jump. The Hero is weak and ends quickly, reinforcing the anti-climactic theme.

Combat is tactical but not deep—more about avoiding enemies to reach goals than fighting them.

RPG Systems: The Mana Stone Economy

A critical innovation is the “mana stone” system, which combines experience points and collectibles:

– Collecting Mana Stones: Found in hidden rooms, behind walls, under breakables.

– Leveling Up: Accumulate stones to gain max health (LP) increases.

– No level cap: But diminishing returns.

– S-rank Potential: Finding all stones allows perfect end-rank, including hidden galleries.

This blends RPG progression with metroidvania collection, creating a multi-layered goal: beat the game, then optimize for completion.

UI & Control: Clunky but Functional

- HUD: Top-left health (LP), top-right mana/stone counter, bottom difficulty/mode.

- Pause Menu: Save (frequent checkpoints), quit, view map (raw tiles, no labels).

- Controls (Keyboard):

- Arrow keys: movement, run (double-tap)

- Z: Jump

- X: Sword

- C: Shoot

- V: Use power

- Enter: Confirm

- Esc: Pause

Major Criticism: Input Lag & Double-Tap Dash

As noted by GameFAQs reviewer 16-BITTER, the “double-tap to run” mechanic is the game’s most archaic, frustrating feature. It forces players to manually repeat an action that should be cued by a single press, breaking flow and creating precision stress during jumps. This is uniquely annoying in a game about movement and momentum.

- Jumping Trajectory: Akuji’s jump arc is not physics-based but fixed-length (like Contra or Mega Man), meaning every jump covers the same horizontal distance if input at the same frame. No floating; no variable height.

- No Jetpack or Corkscrew: Unlike Samus, Akuji cannot adjust trajectory mid-air—increasing difficulty.

However, the control scheme is learnable, and most reviews agree that after 15–20 minutes, players adapt. It’s not broken, but demanding.

Puzzle & Backtracking Depth

Puzzles are spatial, not logic-based:

– “How do I get to the top of the column?”

– “What breaks this wall?”

– “Where are the hidden mana stones?”

Backtracking is non-repetitive due to:

– New enemies in old areas.

– Environmental changes (e.g., collapse blocks).

– Hidden clues (signs in Japanese, translated via patches).

But the lack of an annotated map (only raw tiles) increases map dependency, relying on player skill rather than game aid.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Anime Pastels in a Gothic Prison

Visual Direction: Cute Gothic

The art style is a deliberate juxtaposition:

– Color Palette: Primarily teal, pink, red, and dark gray.

– Sprite Quality: 16×16–32×32 pixel characters, with 12–16 frame animations for walking, jumping, etc.

– Aesthetic: “Cute Gothic”—brutal environments (lava, spikes, darkness) inhabited by adorable, cartoonish characters. This contrast lifts the mood, avoiding horror and embracing whimsy.

– Inspirations: Final Fantasy enemy art, Kirby cuteness, Ikachan’s minimalism.

The backgrounds are tile-rendered with parallax layers, but lack the depth of Castlvainia: Symphony of the Night.

Sound Design: Minimal but Memorable

- Music: Two main tracks loop:

- Exploration theme: Upbeat synth mix, uplifting 8-bit style, with chiptune melodies and electric bass.

- Boss theme: Slightly darker, with drum loop and ominous keys.

- Sfx: Crude but clear—sword clangs, fire whooshes, jump bounces.

- Silence: Open areas use ambient silence, enhancing the feel of isolation.

As noted by FreeHry.cz, the “excellent hudba” (music) contrasts with the game’s dark setting, reinforcing the theme of irony and subversion.

Atmosphere: Isolation with a Smirk

The prison feels abandoned but not haunted. No screaming souls, no grotesque monsters—just empty hallways, broken elevators, and traps. The mood is sad, lonely, but not scary. Akuji isn’t evil here—he’s free.

The gallery feature (unlocked with hidden stones) reveals sketches of enemies, layouts, and character designs, suggesting Hashimoto’s pride in his work and a meta-commentary on game creation.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic Forged in Niche Recognition

Commercial Reception

- Platform: Windows only.

- Release: January 2002, Japan → Global abandonware scene by 2003.

- Monetization: Freeware (3–5 MB download). No revenue model—distributed via direct link, BBS, fan archives.

- Play Stats: Estimated 10,000–50,000 players lifetime (based on abandonware site traffic, patch downloads, HowLongToBeat logs).

Critical Reception

A mixed but largely positive reception:

– MobyGames: 7.5/10, 79% from critics.

– Top Praise:

– GameHippo.com: “One of the best platform games I’ve ever played” (9/10).

– Abandonia Reloaded / Freehare: “90% – Perfect for casual play”.

– Home of the Underdogs: 8.52/10 – “Puts many commercial titles to shame”.

– Top Criticism:

– GameFAQs (16-BITTER): “2/5 – Broken controls”.

– VictoryGames.pl: 60% – “Too cute for a demon game”.

– User-reported: Stiff controls, short length (1–2 hours), no map.

Consensus: A short, polished, charming game with flawed input and zero-day polish issues, but immensely enjoyable.

Player Legacy & Cultural Impact

- Abandonware Adoption: Became a staple of freeware sites (MyAbandonware, Old-Games.com), praised as “the GBA title on PC”.

- Fan Translations: D-Boy’s English patch (early 2000s) was crucial for Western reach. The patch’s unusual copyright enforcement (“do not distribute”) added authenticity and community ethics to the distribution.

- Influence on Indie Games:

- Precursor to mini-Metroidvanias: Paved the way for Eternal Daughter (2002), Lars: The Wanderer, and 9 Hours 9 Persons 9 Doors-style small-scope games.

- Meta-Game Design: Inspired narrative subversion in Crypt of the NecroDancer (demon protagonist), Hyper Demon (self-aware violence).

- The “Enemy POV” Genre: Shadow of the Colossus, Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, Vampyr all inherit the empathetic villain trope rooted in Akuji.

- Cult Status: Voted into GOG Dreamlist, reclaimed by Backloggd, cited by indie devs (@Sgn98 on GOG) as “the game that made me love indie games”.

Historical Significance

Akuji the Demon is one of the earliest non-dating sim doujin soft games from Japan to gain international attention. It represents a phase in democratized game development—before engines, before kickstarter, before itch.io. It’s a time capsule of 2002 Japan’s indie scene, a micro-masterpiece of narrative irony and mechanical creativity, and a blueprint for how small games can make big waves through passion, not budget.

Conclusion: The Demon, the Delusion, and the Durable Legacy

Akuji the Demon is not a flawless game. Its controls are clunky, its duration short, its difficulty uneven, and its graphics dated by modern standards. It will frustrate players expecting Ori and the Blind Forest polish or Hollow Knight depth.

But within its 1.5-hour sandbox, Akuji the Demon achieves something rare: it reframes the entire action-platformer genre by asking, What if the villain succeeded? It’s a satirical, sentimental, and subliminally philosophical exploration of legacy, identity, and memory—delivered through welded-together NES aesthetics, GBA slickness, and PC indie ambition.

E. Hashimoto did not set out to revolutionize gaming. He set out to play his favorite games from the other side. In doing so, he created a minor masterpiece of meta-narrative, mechanical hybridity, and melancholy whimsy. It’s a game that makes you laugh, then makes you think, then makes you want to replay it to find the last six mana stones.

In the pantheon of early indie games, Akuji the Demon stands not alongside Cave Story or Touhou in fame, but alongside Ikachan and Eternal Daughter in purity of vision. It is fleeting, forgettable, and unforgettable—a pink ghost in the machine of game history.

Final Verdict: 8.7 / 10 – A Cult Classic, a Mechanical Quirk, and a Monument to Indie Passion.

It may run too fast on your NVIDIA card. It may crash on Windows 11. But if you cap the FPS, use dgVoodoo2, and download D-Boy’s patch, you’ll find one of the most charming, clever, and enduringly human games ever made about a demon. And that, in itself, is the most monstrous thing of all.